Music, Affect and Atmospheres: Meaning and Meaningfulness in Palauan Omengeredakl

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

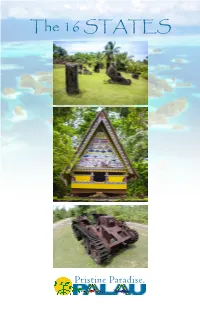

The 16 STATES

The 16 STATES Pristine Paradise. 2 Palau is an archipelago of diverse terrain, flora and fauna. There is the largest island of volcanic origin, called Babeldaob, the outer atoll and limestone islands, the Southern Lagoon and islands of Koror, and the southwest islands, which are located about 250 miles southwest of Palau. These regions are divided into sixteen states, each with their own distinct features and attractions. Transportation to these states is mainly by road, boat, or small aircraft. Koror is a group of islands connected by bridges and causeways, and is joined to Babeldaob Island by the Japan-Palau Friendship Bridge. Once in Babeldaob, driving the circumference of the island on the highway can be done in a half day or full day, depending on the number of stops you would like. The outer islands of Angaur and Peleliu are at the southern region of the archipelago, and are accessable by small aircraft or boat, and there is a regularly scheduled state ferry that stops at both islands. Kayangel, to the north of Babeldaob, can also be visited by boat or helicopter. The Southwest Islands, due to their remote location, are only accessible by large ocean-going vessels, but are a glimpse into Palau’s simplicity and beauty. When visiting these pristine areas, it is necessary to contact the State Offices in order to be introduced to these cultural treasures through a knowledgeable guide. While some fees may apply, your contribution will be used for the preservation of these sites. Please see page 19 for a list of the state offices. -

The Republic of Palau Pursuing a Sustainable and Resilient Energy Future

OIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIAOIA The Republic of Palau Pursuing a Sustainable and Resilient Energy Future The Republic of Palau is located roughly 500 miles east of the Philippines in the Western Pacific Ocean. The country consists of 189 square miles of land spread over more than 340 islands, only nine of which are inhabited: 95% of the land area lies within a single reef structure that includes the islands of Babeldaob (a.k.a. Babelthuap), Peleliu and Koror. Palau and the United States have a strong relationship as enshrined in the Compact of Free Association, U.S. Public Law 99-658. Palau has made a concerted effort in goals set forth in its energy policy. recent years to address the technical, The country completed its National policy, social and economic hurdles Climate Change Policy in 2015 and Energy & Climate Facts to deploying energy efficiency and made a commitment to reduce Total capacity (2015): 40.1 MW renewable energy technologies, and has national greenhouse gas emissions Diesel: 38.8 MW taken measures to mitigate and adapt to (GHGs) as part of the United Nations Solar PV: 1.3 MW climate change. This work is grounded in Framework Convention on Climate Total generation (2014): 78,133 MWh Palau’s 2010 National Energy Policy. Change (UNFCCC). Demand for electricity (2015): Palau has also developed an energy action However with a population of just Average/Peak: 8.9/13.5 MW plan to outline concrete steps the island over 21,000 and a gross national GHG emissions per capita: 13.56 tCO₂e nation could take to achieve the energy income per capita of only US$11,110 (2011) in 2014, Palau will need assistance Residential electric rate: $0.28/kWh 7°45|N (2013 average) Arekalong from the international community in REPUBLIC Peninsula order to fully implement its energy Population (2015): 21,265 OF PALAU and climate goals. -

A Summary of Palau's Typhoon History 1945-2013

A Summary of Palau’s Typhoon History 1945-2013 Coral Reef Research Foundation, Palau Dec, 2014 © Coral Reef Research Foundation 2014 Suggested citation: Coral Reef Research Foundation, 2014. A Summary of Palau’s Typhoon History. Technical Report, 17pp. www.coralreefpalau.org Additions and suggestions welcome. Please email: [email protected] 2 Summary: Since 1945 Palau has had 68 recorded typhoons, tropical storms or tropical depressions come within 200 nmi of its islands or reefs. At their nearest point to Palau, 20 of these were typhoon strength with winds ≥64kts, or an average of 1 typhoon every 3 years. November and December had the highest number of significant storms; July had none over 40 kts and August had no recorded storms. Data Compilation: Storms within 200 nmi (nautical miles) of Palau were identified from the Digital Typhoon, National Institute of Informatics, Japan web site (http://agora.ex.nii.ac.jp/digital- typhoon/reference/besttrack.html.en). The storm tracks and intensities were then obtained from the Joint Typhoon Warning Center (JTWC) (https://metoc.ndbc.noaa.gov/en/JTWC/). Three storm categories were used following the JTWC: Tropical Depression, winds ≤ 33 kts; Tropical Storm, winds 34-63 kts; Typhoon ≥64kts. All track data was from the JTWC archives. Tracks were plotted on Google Earth and the nearest distance to land or reef, and bearing from Palau, were measured; maximum sustained wind speed in knots (nautical miles/hr) at that point was recorded. Typhoon names were taken from the Digital Typhoon site, but typhoon numbers for the same typhoon were from the JTWC archives. -

Socio-Economic Baseline Study of Melekeok State

Technical Report No. 18-06 Socio-economic Baseline Study of Melekeok State PICRC Technical Report No. 18-06 Lincy Marino, Randa Jonathan Palau International Coral Reef Center 1 M-Dock Road P.O. Box 7086 Koror, Palau 96940 February 2018 1 Technical Report No. 18-06 Table of Contents Abstract ........................................................................................................................................................ 3 Introduction and Context ........................................................................................................................... 4 Methods and Study Site ............................................................................................................................ 5 Methods ................................................................................................................................................... 5 Study Site ................................................................................................................................................ 9 Results ....................................................................................................................................................... 11 Socio-demographics ............................................................................................................................ 11 Income and Livelihood activities ........................................................................................................ 14 Fishing Activities .................................................................................................................................. -

National Register of Historic Places Inventory -- Nomination Form

Form No. 10-300 (Rev. 10-74) CbfotfZ 3^3 / UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS I NAME HISTORIC QNGSLULIJUL AND/OR COMMON same LOCATION STREET& NUMBER Uehuladokoe __NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY, TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Melekeok VICINITY OF Babelthuap Island___________ STATE Palau Districtf Trust CODETerritory J of the PacificCOUNTY Islands 96950CODE CLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE —DISTRICT X-PUBLIC —OCCUPIED —AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM _BUILDING(S) —PRIVATE —2JJNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL —PARK —STRUCTURE —BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE _?SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT _RELIGIOUS OBJECT _IN PROCESS X-YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED — YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION _NO, —MILITARY XOTHER: storage [OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME Trust Territory Government/in trust tc? Chief Reklai STREET & NUMBER Okemii Saipan Headquarters Palau District CITY, TOWN STATE VICINITY OF LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDS, ETC. Municipal Office STREET & NUMBER Ngerams CITY, TOWN STATE Melekeok, Babelthuap Island^ TTPI 96950 1 REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE none, DATE —FEDERAL —STATE _COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS CITY, TOWN STATE DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE _EXCELLENT ^DETERIORATED _UNALTERED ^ORIGINAL SITE _GOOD X_RUINS _ALTERED _MOVED DATE. _FAIR _UNEXPOSED ——————————DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE Ongeluluul is a stone platform along the main road te£ Old Melekeok Village to west/southwest further inland about 100 yards from the boathouse along ttef shoreline. The platform is about EO feet by 20 feet separate from the main road by a small creek paralleling the road eastward. -

The Bioarchaeology of Initial Human Settlement in Palau

THE BIOARCHAEOLOGY OF INITIAL HUMAN SETTLEMENT IN PALAU, WESTERN MICRONESIA by JESSICA H. STONE A DISSERTATION Presented to the Department of Anthropology and the Graduate School of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy June 2020 DISSERTATION APPROVAL PAGE Student: Jessica H. Stone Title: The Bioarchaeology of Initial Human Settlement in Palau, Western Micronesia This dissertation has been accepted and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctor of Philosophy degree in the Department of Anthropology by: Scott M. Fitzpatrick Chairperson Nelson Ting Core Member Dennis H. O’Rourke Core Member Stephen R. Frost Core Member James Watkins Institutional Representative and Kate Mondloch Interim Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School Original approval signatures are on file with the University of Oregon Graduate School. Degree awarded June 2020 ii © 2020 Jessica H. Stone iii DISSERTATION ABSTRACT Jessica H. Stone Doctor of Philosophy Department of Anthropology June 2020 Title: The Bioarchaeology of Initial Human Settlement in Palau, Western Micronesia The initial settlement of Remote Oceania represents the world’s last major wave of human dispersal. While transdisciplinary models involving linguistic, archaeological, and biological data have been utilized in the Pacific to develop basic chronologies and trajectories of initial human settlement, a number of elusive gaps remain in our understanding of the region’s colonization history. This is especially true in Micronesia, where a paucity of human skeletal material dating to the earliest periods of settlement have hindered biological contributions to colonization models. The Chelechol ra Orrak site in Palau, western Micronesia, contains the largest and oldest human skeletal assemblage in the region, and is one of only two known sites that represent some of the earliest settlers in the Pacific. -

Download from And

Designation date: 18/10/2002 Ramsar Site no. 1232 Information Sheet on Ramsar Wetlands (RIS) – 2009-2014 version Available for download from http://www.ramsar.org/doc/ris/key_ris_e.doc and http://www.ramsar.org/pdf/ris/key_ris_e.pdf Categories approved by Recommendation 4.7 (1990), as amended by Resolution VIII.13 of the 8th Conference of the Contracting Parties (2002) and Resolutions IX.1 Annex B, IX.6, IX.21 and IX. 22 of the 9th Conference of the Contracting Parties (2005). Notes for compilers: 1. The RIS should be completed in accordance with the attached Explanatory Notes and Guidelines for completing the Information Sheet on Ramsar Wetlands. Compilers are strongly advised to read this guidance before filling in the RIS. 2. Further information and guidance in support of Ramsar site designations are provided in the Strategic Framework and guidelines for the future development of the List of Wetlands of International Importance (Ramsar Wise Use Handbook 17, 4th edition). 3. Once completed, the RIS (and accompanying map(s)) should be submitted to the Ramsar Secretariat. Compilers should provide an electronic (MS Word) copy of the RIS and, where possible, digital copies of all maps. 1. Name and address of the compiler of this form: FOR OFFICE USE ONLY. DD MM Y Y Mr. Kashgar Rengulbai Tel: +680 544 5804/1 0 49 Program Manager Fax: +680 544 5090 Bureau of Agriculture Email: [email protected] Office of the Minister Designation d ate Site Reference Number PO Box 460 Koror, Palau PW 96940 Fax: +680 544 5090 Tel: +680 544 5804/1049 Email: [email protected] 2. -

Final Report on the Master Plan Study for the Upgrading of Electric Power Supply in the Republic of Palau Summary

Palau Public Utilities Corporation No. The Republic of Palau FINAL REPORT ON THE MASTER PLAN STUDY FOR THE UPGRADING OF ELECTRIC POWER SUPPLY IN THE REPUBLIC OF PALAU SUMMARY JULY 2008 JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY YACHIYO ENGINEERING CO., LTD. THE CHUGOKU ELECTRIC POWER CO., INC. IL JR 08-018 PREFACE In response to a request from the Republic of Palau, the Government of Japan decided to conduct the Master Plan Study for the Upgrading of Electric Power Supply and entrusted to the study to the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA). JICA selected and dispatched a study team headed by Mr. Mitsuhisa Nishikawa of Yachiyo Engineering Co., LTD. (yec) and consists of yec and Chugoku Electric Power Co., INC. three times between January and June, 2008. The team held discussions with the officials concerned of the Government of Palau and conducted field surveys at the study area. Upon returning to Japan, the team conducted further studies and prepared this final report. I hope that this report will contribute to the promotion of this project and to the enhancement of friendly relationship between our two countries. Finally, I wish to express my sincere appreciation to the officials concerned of the Government of Palau for their close cooperation extended to the study. July 2008 Seiichi Nagatsuka Vice President Japan International Cooperation Agency Mr. Seiichi Nagatsuka Vice President Japan International Cooperation Agency LETTER OF TRANSMITTAL July 2008 Dear Sir, It is my great pleasure to submit herewith the Final Report of “The Master Plan Study for the Upgrading of Electric Power Supply in the Republic of Palau”. -

Ngchesar State Protected Areas | PAN Site Mesekelat and Ngelukes Conservation Area Ngchesar State Vision Ngelukes Conservation A

Ngchesar State Protected Areas | PAN Site Mesekelat and Ngelukes Conservation Area January 2016 │ Fact Sheet Ngchesar State Ngchesar, also known as "Oldiais" is one of the sixteen states of Palau. It is the sixth largest state in terms of land, with an area of roughly 40 square kilometers, and is located on the eastern side of Babeldaob Island. It is also northwest of Airai State, and southeast of Melekeok State, where the Pa- lau Government Capitol is situated. The sacred totem of Ngchesar is the Stingray. Ngchesar is famous for its war canoe "kabekel" named “bisebush” which means “lightning”. Vision “We, the people of Ngchesar desire to protect and conserve Mesekelat, Ngelukes and Ngchesar in its entirety to ensure that these natural assets are sustained for the benefits of the people of Ngchesar today and into the future.” The Ngchesar State Protected Area System was created with the support from the Ngchesar State Conservation Management Action Plan Team who identified a system of state protected areas in and around Ngchesar and with full endorsement by the community and the leadership of the State. In 2002, Ngchesar State Public Law NSPL No. 146 established Ngchesar State Protected Area System consisting of the following two conservation are- as: Ngelukes Conservation Area Ngelukes Conservation Area is a 1km patch reef in front of Ngersuul village. Ngelukes’s substrate is mostly sand and rubble. Its interior is characterized by sea grass beds. Most of the corals in this patch reef are found along its outer edges along with macroalgae covered rubble. It is a shallow reef, howev- er at its edge there are depths that reach 20 feet at maximum high tide. -

A Decision Support Tool for the Conservation of Tropical Forest and Nearshore Environments on Babeldaob Island, Palau T ⁎ Nicholas A

Forest Ecology and Management 476 (2020) 118480 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Forest Ecology and Management journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/foreco A decision support tool for the conservation of tropical forest and nearshore environments on Babeldaob Island, Palau T ⁎ Nicholas A. Povaka,b, , Christian P. Giardinac, Paul F. Hessburga, Keith M. Reynoldsd, R. Brion Saltera, Chris Heidere, Ed Salminene, Richard MacKenziec a USDA-FS, Pacific Northwest Research Station, Forestry Sciences Laboratory, Wenatchee, WA 98801, United States b Oak Ridge Institute for Science and Education, Oak Ridge, TN 37830, United States c USDA-FS, Pacific Southwest Research Station, Institute of Pacific Islands Forestry, Hilo, HI 96720, United States d USDA-FS, Pacific Northwest Research Station, Forestry Sciences Laboratory, Corvallis, OR 97331, United States e Watershed Professionals Network (WPN), PO Box 8, Mount Hood-Parkdale, OR 970441, United States ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: Nearshore ecosystems (e.g., mangrove forests, sea grass beds, coral reefs) are some of the most biologically Palau diverse and ecologically productive on Earth, while providing essential goods and services to human commu- nearshore environments nities. Because these ecosystems are subject to threats from both land and sea, their conservation and man- sediment agement requires a ridge to reef approach. Here, we developed a watershed decision support tool (DST) for DHSVM Babeldaob Island, Republic of Palau, aimed at prioritizing catchments for reforestation of fire degraded savanna decision support or protection of native forest against conversion to savanna. We use a distributed hydrology model to estimate EMDS catchment-level sedimentation and water yield for three vegetation scenarios: (1) current vegetation; (2) a hypothetical fully-forested Babeldaob Island; and (3) a hypothetical Babeldaob Island that has been fully con- verted to savanna. -

Palau: Typhoon Haiyan - Initial Damage Assessment Reports As at 22 November 2013 134°30'0"E 134°40'0"E ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !

Palau: Typhoon Haiyan - Initial Damage Assessment reports as at 22 November 2013 134°30'0"E 134°40'0"E ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 134°0'0"E 134°30'0"E ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Classroom roof damaged ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Mini Census 201! 2 Preliminary IDA results - Household Damage (as at Nov 22, 2013) ! ! ! ! ! ! Est. cost - $150,000 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! No No Significant Minor Major ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! State ! Destroyed Total HH Ngarchelong ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Households Popula! tion Damage Damage Damage Damage ! ! ! ! Elementary ! ! ! ! ! Iungel ! ! Damaged ! ! ! ! Ï ! Ngatmel ! ! School ! ! Level 0 Level 1 Level 2 Level 3 Level 4 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Meteolchol ! ! ! ! ! ! Ollei ! ! ! ! n ! ! Aimeliik 94 281 75 12 4 1 2 19 ! ! ! Inset ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! N N ! ! ! ! " " ! ! 8 12 12 3 ! Airai 719 ! 2537 684 35 ! ! ! ! 0 0 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ' ' ! ! ! ! ! ! 0 0 ! ! Kayangel ! ! ! ° ° ! ! Angaur 52 ! 130 52 0 0 0 0 0 ! ! ! ! 8 8 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Kayangel 41 76 4 0 0 15 22 37 ! ! Ngerbau ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Ngebei ! ! Koror 3037 11665 2892 77 41 23 4 145 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Melekeok 108 299 102 4 0 2 0 6 ! ! ! ! ! NGARCHELONG STATE ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Main Map ! ! ! ! ! Mengellang ! Ngaraard 163 453 102 25 23 9 4 61 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Oketol Ngriil ! ! ! Ngarchelong 117 ! 281 45 42 12 14 4 72 ! ! -

Wikipedia on Palau

Palau From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Jump to: navigation, search This article is about the country. For other uses, see Palau (disambiguation). Republic of Palau Beluu ęr a Belau Flag Seal Anthem: Belau loba klisiich er a kelulul Palau is circled in green. Melekeok[1] Capital 7°21′N 134°28′E Largest city Koror Official language(s) English Palauan Japanese (in Angaur) Recognised regional languages Sonsorolese (in Sonsoral) Tobian (in Hatohobei) Demonym Palauan Government Unitary presidential democratic republic - President Johnson Toribiong - Vice President Kerai Mariur Legislature National Congress Independence 2 Compact of Free - Association with United October 1, 1994 States Area 2 - Total 459 km (196th) 177 sq mi - Water (%) negligible Population - 2011 estimate 20,956 (218th) 2 - Density 28.4/km 45.5/sq mi GDP (PPP) 2008 estimate [2] - Total $164 million (2008 est.) (not ranked) - Per capita $8,100[2] (119th) HDI (2011) 0.782[3] (high) (49th) Currency United States dollar (USD) Time zone (UTC+9) Drives on the right ISO 3166 code PW Internet TLD .pw Calling code +680 On October 7, 2006, government officials moved their offices in the former capital of Koror to Ngerulmud in 1State of Melekeok, located 20 km (12 mi) northeast of Koror on Babelthaup Island and 2 km (1 mi) northwest of Melekeok village. 2GDP estimate includes US subsidy (2004 estimate). Palau ( i/pəˈlaʊ/, sometimes spelled Belau or Pelew), officially the Republic of Palau (Palauan: Beluu ęr a Belau), is an island country located in the western Pacific Ocean. Geographically part of the larger island group of Micronesia, with the country’s population of around 21,000 people spread out over 250 islands forming the western chain of the Caroline Islands.