Tidal Heating in Enceladus

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![Arxiv:1912.09192V2 [Astro-Ph.EP] 24 Feb 2020](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2925/arxiv-1912-09192v2-astro-ph-ep-24-feb-2020-2925.webp)

Arxiv:1912.09192V2 [Astro-Ph.EP] 24 Feb 2020

Draft version February 25, 2020 Typeset using LATEX preprint style in AASTeX62 Photometric analyses of Saturn's small moons: Aegaeon, Methone and Pallene are dark; Helene and Calypso are bright. M. M. Hedman,1 P. Helfenstein,2 R. O. Chancia,1, 3 P. Thomas,2 E. Roussos,4 C. Paranicas,5 and A. J. Verbiscer6 1Department of Physics, University of Idaho, Moscow, ID 83844 2Cornell Center for Astrophysics and Planetary Science, Cornell University, Ithaca NY 14853 3Center for Imaging Science, Rochester Institute of Technology, Rochester NY 14623 4Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research, G¨ottingen,Germany 37077 5APL, John Hopkins University, Laurel MD 20723 6Department of Astronomy, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA 22904 ABSTRACT We examine the surface brightnesses of Saturn's smaller satellites using a photometric model that explicitly accounts for their elongated shapes and thus facilitates compar- isons among different moons. Analyses of Cassini imaging data with this model reveals that the moons Aegaeon, Methone and Pallene are darker than one would expect given trends previously observed among the nearby mid-sized satellites. On the other hand, the trojan moons Calypso and Helene have substantially brighter surfaces than their co-orbital companions Tethys and Dione. These observations are inconsistent with the moons' surface brightnesses being entirely controlled by the local flux of E-ring par- ticles, and therefore strongly imply that other phenomena are affecting their surface properties. The darkness of Aegaeon, Methone and Pallene is correlated with the fluxes of high-energy protons, implying that high-energy radiation is responsible for darkening these small moons. Meanwhile, Prometheus and Pandora appear to be brightened by their interactions with nearby dusty F ring, implying that enhanced dust fluxes are most likely responsible for Calypso's and Helene's excess brightness. -

The Orbits of Saturn's Small Satellites Derived From

The Astronomical Journal, 132:692–710, 2006 August A # 2006. The American Astronomical Society. All rights reserved. Printed in U.S.A. THE ORBITS OF SATURN’S SMALL SATELLITES DERIVED FROM COMBINED HISTORIC AND CASSINI IMAGING OBSERVATIONS J. N. Spitale CICLOPS, Space Science Institute, 4750 Walnut Street, Suite 205, Boulder, CO 80301; [email protected] R. A. Jacobson Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology, 4800 Oak Grove Drive, Pasadena, CA 91109-8099 C. C. Porco CICLOPS, Space Science Institute, 4750 Walnut Street, Suite 205, Boulder, CO 80301 and W. M. Owen, Jr. Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology, 4800 Oak Grove Drive, Pasadena, CA 91109-8099 Received 2006 February 28; accepted 2006 April 12 ABSTRACT We report on the orbits of the small, inner Saturnian satellites, either recovered or newly discovered in recent Cassini imaging observations. The orbits presented here reflect improvements over our previously published values in that the time base of Cassini observations has been extended, and numerical orbital integrations have been performed in those cases in which simple precessing elliptical, inclined orbit solutions were found to be inadequate. Using combined Cassini and Voyager observations, we obtain an eccentricity for Pan 7 times smaller than previously reported because of the predominance of higher quality Cassini data in the fit. The orbit of the small satellite (S/2005 S1 [Daphnis]) discovered by Cassini in the Keeler gap in the outer A ring appears to be circular and coplanar; no external perturbations are appar- ent. Refined orbits of Atlas, Prometheus, Pandora, Janus, and Epimetheus are based on Cassini , Voyager, Hubble Space Telescope, and Earth-based data and a numerical integration perturbed by all the massive satellites and each other. -

Titan and the Moons of Saturn Telesto Titan

The Icy Moons and the Extended Habitable Zone Europa Interior Models Other Types of Habitable Zones Water requires heat and pressure to remain stable as a liquid Extended Habitable Zones • You do not need sunlight. • You do need liquid water • You do need an energy source. Saturn and its Satellites • Saturn is nearly twice as far from the Sun as Jupiter • Saturn gets ~30% of Jupiter’s sunlight: It is commensurately colder Prometheus • Saturn has 82 known satellites (plus the rings) • 7 major • 27 regular • 4 Trojan • 55 irregular • Others in rings Titan • Titan is nearly as large as Ganymede Titan and the Moons of Saturn Telesto Titan Prometheus Dione Titan Janus Pandora Enceladus Mimas Rhea Pan • . • . Titan The second-largest moon in the Solar System The only moon with a substantial atmosphere 90% N2 + CH4, Ar, C2H6, C3H8, C2H2, HCN, CO2 Equilibrium Temperatures 2 1/4 Recall that TEQ ~ (L*/d ) Planet Distance (au) TEQ (K) Mercury 0.38 400 Venus 0.72 291 Earth 1.00 247 Mars 1.52 200 Jupiter 5.20 108 Saturn 9.53 80 Uranus 19.2 56 Neptune 30.1 45 The Atmosphere of Titan Pressure: 1.5 bars Temperature: 95 K Condensation sequence: • Jovian Moons: H2O ice • Saturnian Moons: NH3, CH4 2NH3 + sunlight è N2 + 3H2 CH4 + sunlight è CH, CH2 Implications of Methane Free CH4 requires replenishment • Liquid methane on the surface? Hazy atmosphere/clouds may suggest methane/ ethane precipitation. The freezing points of CH4 and C2H6 are 91 and 92K, respectively. (Titan has a mean temperature of 95K) (Liquid natural gas anyone?) This atmosphere may resemble the primordial terrestrial atmosphere. -

Observing the Universe

ObservingObserving thethe UniverseUniverse :: aa TravelTravel ThroughThrough SpaceSpace andand TimeTime Enrico Flamini Agenzia Spaziale Italiana Tokyo 2009 When you rise your head to the night sky, what your eyes are observing may be astonishing. However it is only a small portion of the electromagnetic spectrum of the Universe: the visible . But any electromagnetic signal, indipendently from its frequency, travels at the speed of light. When we observe a star or a galaxy we see the photons produced at the moment of their production, their travel could have been incredibly long: it may be lasted millions or billions of years. Looking at the sky at frequencies much higher then visible, like in the X-ray or gamma-ray energy range, we can observe the so called “violent sky” where extremely energetic fenoena occurs.like Pulsar, quasars, AGN, Supernova CosmicCosmic RaysRays:: messengersmessengers fromfrom thethe extremeextreme universeuniverse We cannot see the deep universe at E > few TeV, since photons are attenuated through →e± on the CMB + IR backgrounds. But using cosmic rays we should be able to ‘see’ up to ~ 6 x 1010 GeV before they get attenuated by other interaction. Sources Sources → Primordial origin Primordial 7 Redshift z = 0 (t = 13.7 Gyr = now ! ) Going to a frequency lower then the visible light, and cooling down the instrument nearby absolute zero, it’s possible to observe signals produced millions or billions of years ago: we may travel near the instant of the formation of our universe: 13.7 By. Redshift z = 1.4 (t = 4.7 Gyr) Credits A. Cimatti Univ. Bologna Redshift z = 5.7 (t = 1 Gyr) Credits A. -

Blocks Size Frequency Distribution in the Enceladus Tiger Stripes Area: Implications on Their Formative Processes

universe Article Blocks Size Frequency Distribution in the Enceladus Tiger Stripes Area: Implications on Their Formative Processes Maurizio Pajola 1,* , Alice Lucchetti 1 , Lara Senter 2 and Gabriele Cremonese 1 1 INAF-Astronomical Observatory of Padova, Vicolo dell’Osservatorio 5, 35122 Padova, Italy; [email protected] (A.L.); [email protected] (G.C.) 2 Department of Physics and Astronomy “G. Galilei”, Università di Padova, 35122 Padova, Italy; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: We study the size frequency distribution of the blocks located in the deeply fractured, geologically active Enceladus South Polar Terrain with the aim to suggest their formative mechanisms. Through the Cassini ISS images, we identify ~17,000 blocks with sizes ranging from ~25 m to 366 m, and located at different distances from the Damascus, Baghdad and Cairo Sulci. On all counts and for both Damascus and Baghdad cases, the power-law fitting curve has an index that is similar to the one obtained on the deeply fractured, actively sublimating Hathor cliff on comet 67P/Churyumov- Gerasimenko, where several non-dislodged blocks are observed. This suggests that as for 67P, sublimation and surface stresses favor similar fractures development in the Enceladus icy matrix, hence resulting in comparable block disaggregation. A steeper power-law index for Cairo counts may suggest a higher degree of fragmentation, which could be the result of localized, stronger tectonic disruption of lithospheric ice. Eventually, we show that the smallest blocks identified are located Citation: Pajola, M.; Lucchetti, A.; from tens of m to 20–25 km from the Sulci fissures, while the largest blocks are found closer to the Senter, L.; Cremonese, G. -

Moons of Saturn

National Aeronautics and Space Administration 0 300,000,000 900,000,000 1,500,000,000 2,100,000,000 2,700,000,000 3,300,000,000 3,900,000,000 4,500,000,000 5,100,000,000 5,700,000,000 kilometers Moons of Saturn www.nasa.gov Saturn, the sixth planet from the Sun, is home to a vast array • Phoebe orbits the planet in a direction opposite that of Saturn’s • Fastest Orbit Pan of intriguing and unique satellites — 53 plus 9 awaiting official larger moons, as do several of the recently discovered moons. Pan’s Orbit Around Saturn 13.8 hours confirmation. Christiaan Huygens discovered the first known • Mimas has an enormous crater on one side, the result of an • Number of Moons Discovered by Voyager 3 moon of Saturn. The year was 1655 and the moon is Titan. impact that nearly split the moon apart. (Atlas, Prometheus, and Pandora) Jean-Dominique Cassini made the next four discoveries: Iapetus (1671), Rhea (1672), Dione (1684), and Tethys (1684). Mimas and • Enceladus displays evidence of active ice volcanism: Cassini • Number of Moons Discovered by Cassini 6 Enceladus were both discovered by William Herschel in 1789. observed warm fractures where evaporating ice evidently es- (Methone, Pallene, Polydeuces, Daphnis, Anthe, and Aegaeon) The next two discoveries came at intervals of 50 or more years capes and forms a huge cloud of water vapor over the south — Hyperion (1848) and Phoebe (1898). pole. ABOUT THE IMAGES As telescopic resolving power improved, Saturn’s family of • Hyperion has an odd flattened shape and rotates chaotically, 1 2 3 1 Cassini’s visual known moons grew. -

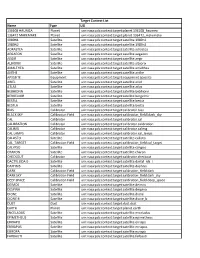

PDS4 Context List

Target Context List Name Type LID 136108 HAUMEA Planet urn:nasa:pds:context:target:planet.136108_haumea 136472 MAKEMAKE Planet urn:nasa:pds:context:target:planet.136472_makemake 1989N1 Satellite urn:nasa:pds:context:target:satellite.1989n1 1989N2 Satellite urn:nasa:pds:context:target:satellite.1989n2 ADRASTEA Satellite urn:nasa:pds:context:target:satellite.adrastea AEGAEON Satellite urn:nasa:pds:context:target:satellite.aegaeon AEGIR Satellite urn:nasa:pds:context:target:satellite.aegir ALBIORIX Satellite urn:nasa:pds:context:target:satellite.albiorix AMALTHEA Satellite urn:nasa:pds:context:target:satellite.amalthea ANTHE Satellite urn:nasa:pds:context:target:satellite.anthe APXSSITE Equipment urn:nasa:pds:context:target:equipment.apxssite ARIEL Satellite urn:nasa:pds:context:target:satellite.ariel ATLAS Satellite urn:nasa:pds:context:target:satellite.atlas BEBHIONN Satellite urn:nasa:pds:context:target:satellite.bebhionn BERGELMIR Satellite urn:nasa:pds:context:target:satellite.bergelmir BESTIA Satellite urn:nasa:pds:context:target:satellite.bestia BESTLA Satellite urn:nasa:pds:context:target:satellite.bestla BIAS Calibrator urn:nasa:pds:context:target:calibrator.bias BLACK SKY Calibration Field urn:nasa:pds:context:target:calibration_field.black_sky CAL Calibrator urn:nasa:pds:context:target:calibrator.cal CALIBRATION Calibrator urn:nasa:pds:context:target:calibrator.calibration CALIMG Calibrator urn:nasa:pds:context:target:calibrator.calimg CAL LAMPS Calibrator urn:nasa:pds:context:target:calibrator.cal_lamps CALLISTO Satellite urn:nasa:pds:context:target:satellite.callisto -

Saturn's Moons and Rings Ring Overview What Creates the Rings?

Saturn's Moons and Rings • We have already discussed a few details of Saturn's ring system • It is impossible to fully discuss the rings without mentioning the interactions with Saturn's many moons •_ • The rings themselves may have been formed from a current or past moon Ring Overview • The rings were named alphabetically in order of discovery •_ • The D ring is a faint ring close to Saturn's cloud tops • The F and G rings and faint and narrow, outside the A ring • The E ring is a large, low density ring in a more distant orbit around Saturn What Creates the Rings? • One clue to ring formation is where they are located compared to their host planet • For each of the 4 outer planets, rings are usually not seen anywhere past about 2.4 times the planet's radius •_ 1 The Roche Limit •_ • Remember that gravity acts to squeeze moons that are close to the planet • If the moon comes close enough, the moon is stretched to the point that it is destroyed Ring Formation • The fact that Saturn's rings are inside the Roche limit explains why they do not clump to form a new moon • How did they form in the first place? – They could possibly be left over material from the formation of Saturn –_ – A comet (like Shoemaker-Levy 9) could have come close to Saturn and broken up around the planet – An impact with one of Saturn's current or past moons may have generated the material in the rings How Old Are The Rings? • _ • The rings are very bright, suggesting they haven't been covered by lots of interplanetary dust over time • The interactions and disturbances -

Horsing Around on Saturn

Horsing Around on Saturn Robert J. Vanderbei Operations Research and Financial Engineering, Princeton University [email protected] ABSTRACT Based on simple statistical mechanical models, the prevailing view of Sat- urn’s rings is that they are unstable and must therefore have been formed rather recently. In this paper, we argue that Saturn’s rings and inner moons are in much more stable orbits than previously thought and therefore that they likely formed together as part of the initial formation of the solar system. To make this argument, we give a detailed description of so-called horseshoe orbits and show that this horseshoeing phenomenon greatly stabilizes the rings of Saturn. This paper is part of a collaborative effort with E. Belbruno and J.R. Gott III. For a description of their part of the work, see their papers in these proceedings. 1. Introduction The currently accepted view (see, e.g., Goldreich and Tremaine (1982)) of the formation of Saturn’s rings is that a moon-sized object wandered inside Saturn’s Roche limit and was torn apart by tidal forces. The resulting array of remnant masses was dispersed and formed the rings we see today. In this model, the system dynamics are treated as a turbulent flow with no explicit mention of the law of gravitation. The ring shape is presumed to be maintained by the coralling effect of a few of the inner moons acting as so-called shepherds. Of course, a simpler explanation would be that the rings formed along with the planets and their moons as they condensed out of the solar nebula. -

Determining the Small-Scale Structure and Particle Properties in Saturn's Rings from Stellar and Radio Occultations

University of Central Florida STARS Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 2018 Determining the Small-scale Structure and Particle Properties in Saturn's Rings from Stellar and Radio Occultations Richard Jerousek University of Central Florida Part of the The Sun and the Solar System Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Doctoral Dissertation (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Jerousek, Richard, "Determining the Small-scale Structure and Particle Properties in Saturn's Rings from Stellar and Radio Occultations" (2018). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019. 5840. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/5840 DETERMINING THE SMALL-SCALE STRUCTURE AND PARTICLE PROPERTIES IN SATURN’S RINGS FROM STELLAR AND RADIO OCCULTATIONS by RICHARD GREGORY JEROUSEK M.S. University of Central Florida, 2009 A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Physics in the College of Sciences at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Spring Term 2018 Major Professor: Joshua E. Colwell © 2018 Richard G. Jerousek ii ABSTRACT Saturn’s rings consist of icy particles of various sizes ranging from millimeters to several meters. Particles may aggregate into ephemeral elongated clumps known as self-gravity wakes in regions where the surface mass density and epicyclic frequency give a Toomre critical wavelength which is much larger than the largest individual particles (Julian and Toomre 1966). -

Spin-Orbit Secondary Resonance Dynamics of Enceladus J

The Astronomical Journal, 128:484–491, 2004 July # 2004. The American Astronomical Society. All rights reserved. Printed in U.S.A. SPIN-ORBIT SECONDARY RESONANCE DYNAMICS OF ENCELADUS J. Wisdom Department of Earth, Atmospheric, and Planetary Sciences, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 77 Massachusetts Avenue, Cambridge, MA 02139; [email protected] Received 2003 November 12; accepted 2004 March 16 ABSTRACT For Enceladus the frequency of small-amplitude oscillations about the synchronous rotation state is approx- imately one-third the orbital frequency. Near this commensurability a period-three bifurcation occurs; on a surface of section a period-three chain of secondary islands appears near the synchronous island center. Forced libration in this resonance may be large and would imply large tidal heating. This paper explores the possibility that Enceladus is or once was locked in this period-three librational resonance, and that the observed resurfacing of Enceladus is a consequence. Key words: celestial mechanics — gravitation — methods: analytical — methods: numerical — planets and satellites: individual (Enceladus, Mimas, Saturn) — planets and satellites: formation 1. INTRODUCTION scenario does not pass the Mimas test. There are also numerous questionable aspects of the dynamics. Enceladus, now there’s a puzzle. A substantial portion of Ross & Schubert (1989) found that estimates of tidal the imaged surface of Enceladus is covered by smooth plains heating with a viscoelastic Maxwell rheology can be sub- that are nearly crater-free. From the crater density, these plains stantially larger than for Darwin models with a bulk effective are estimated to be less than a billion years old, perhaps less tidal Q. They considered both homogeneous ice models and than 100 million years old. -

Mission Science Highlights and Science Objectives Assessment

CASSINI FINAL MISSION REPORT 2019 1 MISSION SCIENCE HIGHLIGHTS AND SCIENCE OBJECTIVES ASSESSMENT Cassini-Huygens, humanity’s most distant planetary orbiter and probe to date, provided the first in- depth, close up study of Saturn, its magnificent rings and unique moons, including Titan and Enceladus, and its giant magnetosphere. Discoveries from the Cassini-Huygens mission revolutionized our understanding of the Saturn system and fundamentally altered many of our concepts of where life might be found in our solar system and beyond. Cassini-Huygens arrived at Saturn in 2004, dropped the parachuted probe named Huygens to study the atmosphere and surface of Saturn’s planet-sized moon Titan, and orbited Saturn for the next 13 years making remarkable discoveries. When it was running low on fuel, the Cassini orbiter was programmed to vaporize in Saturn’s atmosphere in 2017 to protect the ocean worlds, Enceladus and Titan, where it discovered potential habitats for life. CASSINI FINAL MISSION REPORT 2019 2 CONTENTS MISSION SCIENCE HIGHLIGHTS AND SCIENCE OBJECTIVES ASSESSMENT ........................................................ 1 Executive Summary................................................................................................................................................ 5 Origin of the Cassini Mission ....................................................................................................................... 5 Instrument Teams and Interdisciplinary Investigations ...............................................................................