Introduction: Staging Justice

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

I 'A MAN MOSTE MEETE': a NATIONWIDE SURVEY OF

'A MAN MOSTE MEETE': A NATIONWIDE SURVEY OF JUSTICES OF THE PEACE IN MID-TUDOR ENGLAND, 1547-1582 _____________ A Dissertation Presented to The Faculty of the Department of History University of Houston _____________ In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy _____________ By Clarissa Elisabeth Hinojosa May 2014 i 'A MAN MOSTE MEETE': A NATIONWIDE SURVEY OF JUSTICES OF THE PEACE IN MID-TUDOR ENGLAND, 1547-1582 _____________ An Abstract of a Dissertation Presented to The Faculty of the Department of History University of Houston _____________ In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy _____________ By Clarissa Elisabeth Hinojosa May 2014 ii ABSTRACT This dissertation is a national study of English justices of the peace (JPs) in the mid- Tudor era. It incorporates comparable data from the reigns of Edward VI, Mary I, and the Elizabeth I. Much of the analysis is quantitative in nature: chapters compare the appointments of justices of the peace during the reigns of Edward VI, Mary I, and Elizabeth I, and reveal that purges of the commissions of the peace were far more common than is generally believed. Furthermore, purges appear to have been religiously- based, especially during the reign of Elizabeth I. There is a gap in the quantitative data beginning in 1569, only eleven years into Elizabeth I’s reign, which continues until 1584. In an effort to compensate for the loss of quantitative data, this dissertation analyzes a different primary source, William Lambarde’s guidebook for JPs, Eirenarcha. The fourth chapter makes particular use of Eirenarcha, exploring required duties both in and out of session, what technical and personal qualities were expected of JPs, and how well they lived up to them. -

Part Two Patrons and Printers

PART TWO PATRONS AND PRINTERS CHAPTER VI PATRONAGE The Significance of Dedications The Elizabethan period was a watershed in the history of literary patronage. The printing press had provided a means for easier publication, distribution and availability of books; and therefore a great patron, the public, was accessible to all authors who managed to get Into print. In previous times there were too many discourage- ments and hardships to be borne so that writing attracted only the dedicated and clearly talented writer. In addition, generous patrons were not at all plentiful and most authors had to be engaged in other occupations to make a living. In the last half of the sixteenth century, a far-reaching change is easily discernible. By that time there were more writers than there were patrons, and a noticeable change occurred In the relationship between patron and protge'. In- stead of a writer quietly producing a piece of literature for his patron's circle of friends, as he would have done in medieval times, he was now merely one of a crowd of unattached suitors clamouring for the favours and benefits of the rich. Only a fortunate few were able to find a patron generous enough to enable them to live by their pen. 1 Most had to work at other vocations and/or cultivate the patronage of the public and the publishers. •The fact that only a small number of persons had more than a few works dedicated to them indicates the difficulty in finding a beneficent patron. An examination of 568 dedications of religious works reveals that only ten &catees received more than ten dedications and only twelve received between four and nine. -

1 Viewing the Changing 'Shape Or Pourtraicture of Britain' in William Camden's Britannia, 1586–1610 Stuart Morrison

Viewing the Changing ‘shape or pourtraicture of Britain’ in William Camden’s Britannia, 1586–1610 Stuart Morrison The University of Kent [email protected] William Camden’s chorographical narratives of nationhood have long been lauded as exemplary texts due to their breadth and depth of learning. They are also exemplary in that they show us how chorography, as a relatively recent import from Europe, was used by the likes of Camden to work through the interactions between: words and images; history and antiquarian study; time and space; and Britain and Continental Europe. This article will investigate these various interactions with a consideration of the continental influences on Camden’s writing. In doing so, this article will argue that these influences had a special influence on the typography and use of images in Camden’s narratives. Much has been written about Camden as historian, antiquarian, and herald and these studies have made valuable contributions to our understanding of him and his writings. Here we will consider these aspects of Camden’s work alongside his career as school master at Westminster in order to support the argument for the influence of European humanism on Camden’s professional life. Writing about ‘Camden’s Britannia’ as a discrete entity is problematic as it presents the various editions as interchangeable and essentially identical. Here it is more rewarding to discuss Camden’s Britannias and to consider the importance of the editorial alterations of the successive versions of the narrative. This article will focus primarily on the first vernacular edition, Britain (1610), with reference to the earlier Latin editions to provide a comparative study where necessary. -

William Lambarde's Eirenarcha and the Centralization of Local Government

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository Graduate Studies The Vault: Electronic Theses and Dissertations 2020-05-04 William Lambarde's Eirenarcha and the Centralization of Local Government LeClair, Stacey Crystal LeClair, S. C. (2020). William Lambarde's Eirenarcha and the Centralization of Local Government (Unpublished master's thesis). University of Calgary, Calgary, AB. http://hdl.handle.net/1880/111991 master thesis University of Calgary graduate students retain copyright ownership and moral rights for their thesis. You may use this material in any way that is permitted by the Copyright Act or through licensing that has been assigned to the document. For uses that are not allowable under copyright legislation or licensing, you are required to seek permission. Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY William Lambarde's Eirenarcha and the Centralization of Local Government by Stacey Crystal LeClair A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS GRADUATE PROGRAM IN HISTORY CALGARY, ALBERTA MAY, 2020 © Stacey Crystal LeClair 2020 Abstract William Lambarde played a pivotal role in the centralization of local government in late Elizabethan England. Although he has been frequently referenced in history as a legal scholar and antiquarian, his widely read manual for the justices of the peace, Eirenarcha: Or, of the Office of the Justices of the Peace (1582), demonstrates that his knowledge of the history of the common law enabled him to critically analyze the operations of local government in an effort to reform the way judicial administration was conducted by lay justices of the peace. -

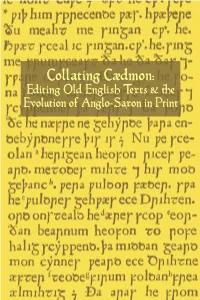

Collating Caedmon: Editing Old English Texts & the Evolution Of

Collating Cædmon: Editing Old English Texts & ªe Evolution of Anglo-Saxon in Print Collating Cædmon: Editing Old English Texts & ªe Evolution of Anglo-Saxon in Print an exhibition curated by Patrick D. Olson Urbana, Illinois The Rare Book & Manuscript Library Catalog of an exhibition held 6 March through 30 April 2009 in The Rare Book & Manuscript Library of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Designed and typeset by Christopher D. Cook in Adobe Caslon Pro Photography by Dennis J. Sears ISBN 978-0-9788134-4-4 Copyright © 2009 by The Rare Book & Manuscript Library and the Board of Trustees of the University of Illinois All rights reserved Manufactured in the United States of America Introduction The corpus of Old English literature, which spans five centuries (ca. 643– 1154), may not seem vast when compared to the vernacular output of early continental cultures. The Anglo-Saxon culture was an oral one, and remained so even as Britain entered the twelfth century. Texts were transcribed at the caprice of Christian monks, whose primary language was Latin and whose interest in the vernacular literature—especially the secular variety—was understandably low. There is no extant Old English prose outside the legal realm that predates King Alfred (849–99). As far as poetry is concerned, we possess about 31,000 lines of Old English verse, largely confined to only four manuscripts, dating from roughly the year 1000—relatively late, consider- ing the Anglo-Saxon period officially ended with the Norman Conquest in 1066. To make matters worse, Viking invaders ransacked and ruined many libraries, and, as Michael Alexander notes, “during the centuries after the Norman Conquest surviving Old English manuscripts became unintelligible and apparently valueless” (3). -

Patents and Patronage: the Life and Career of John Day, Tudor Printer

PATENTS AND PATRONAGE: THE LIFE AND CAREER OF JOHN DAY, TUDOR PRINTER ELIZABETH EVENDEN DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH AND RELATED LITERATURE NOVEMBER 2002 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page List of Illustrations vi Acknowledgements vii Declaration viii Abstract ix Abbreviations x CHAPTER 1 Introduction 1 From Manuscript to Print 3 The Triumph of Print 8 The Era of the Hand-Press 10 Finance and Raw Materials 11 Printing Type 15 Staff and Wages 19 Book Shops 21 CHAPTER 2 23 Apprenticeship and Early Works 26 Partnership with William Seres 30 The Threat of Arrest 34 Day's New Premises and his 38 Connections to the nearby Stranger Communities ii CHAPTER 2 (cont.) The End of Partnership with 40 William Seres The Securing of Letters Patent 44 CHAPTER 3 The Michael Wood Press 49 Proof that John Day was the Printer of 52 The Michael Wood Press The Fall of the Michael Wood Press 56 Where Day was not 1555-1558 61 Where Day really was 1555-1558 64 CHAPTER 4 1558-1563: The Return to Protestant 73 Printing The Metrical Psalms — the beginning of 75 The lucrative Elizabethan patents Works for the Dutch Church 82 Sermons and 'steady sellers' 85 William Cunningham's Cosmographical 91 Glasse Printing Protestant Divines 94 John Foxe 98 The First Edition of John Foxe's 102 Acts and Monuments CHAPTER 5 1563-1570: The Effects of the Acts and 108 Monuments on Day ill CHAPTER 5 (cont.) The loss of time 112 Music Printing and Thomas Caustun 117 Letters of the Martyrs 120 Political Protection and Patronage 124 Day's Technical Achievements: 131 Improvements in -

Commoning of the Common Law: the Renaissance Debate Over Printing English Law, 1520-1640

University of Pennsylvania Law Review FOUNDED 1852 Formerly American Law Register VOL. 146 JANUARY1998 No. 2 ARTICLES THE COMMONING OF THE COMMON LAW: THE RENAISSANCE DEBATE OVER PRINTING ENGLISH LAW, 1520-1640 RIGHARDJ. Rosst I. WHYWAs ITACCEPTABLE TO PRINT IAW? ........................................... 329 A. H umanism ..................................................................................... 329 t Assistant Professor of Law, University of Chicago Law School. J.D. Yale, 1989; M. Phil. Yale, 1990. For comments and advice, I would like to thank Mary Bilder, Edward Cook, John Demos, Charles Donahue, Richard Epstein, Charles Gray, Peter Hoffer, Morton Horwitz, Stanley Katz, Daniel Klerman, David Lieberman, William Novak, Barbara Shapiro, Peter Stein, James Whitman, and participants in workshops at Harvard, New York University, and the University of Chicago. I especially benefited from the challenging questions of Thomas Green, Richard Helmholz, Steven Pincus, Jacqueline Ross, and Steven Wil. Joanna Grisinger provided excellent research assis- tance. I am grateful for the financial assistance of the Frieda and Arnold Shure Fund and the Bernard G. Sang Fund. (323) 324 UN!VERSITY OFPENNSYLVANIA LAWREVIEW [Vol. 146:323 B. Protestantism.................................................................................. 342 II. THE DEBATE OVER THE RISKS AND ADVANTAGES OF PUBLISHING LAW: PUBLICISTS AND ANTI-PUBLICISTS .............................................. 352 A. ForensicBoundaries ....................................................................... -

Magna Carta, Ancient Constitution, and the Anglo-American Tradition of Rule of Law [1993]

The Online Library of Liberty A Project Of Liberty Fund, Inc. Ellis Sandoz, The Roots of Liberty: Magna Carta, Ancient Constitution, and the Anglo-American Tradition of Rule of Law [1993] The Online Library Of Liberty This E-Book (PDF format) is published by Liberty Fund, Inc., a private, non-profit, educational foundation established in 1960 to encourage study of the ideal of a society of free and responsible individuals. 2010 was the 50th anniversary year of the founding of Liberty Fund. It is part of the Online Library of Liberty web site http://oll.libertyfund.org, which was established in 2004 in order to further the educational goals of Liberty Fund, Inc. To find out more about the author or title, to use the site's powerful search engine, to see other titles in other formats (HTML, facsimile PDF), or to make use of the hundreds of essays, educational aids, and study guides, please visit the OLL web site. This title is also part of the Portable Library of Liberty DVD which contains over 1,000 books and quotes about liberty and power, and is available free of charge upon request. The cuneiform inscription that appears in the logo and serves as a design element in all Liberty Fund books and web sites is the earliest-known written appearance of the word “freedom” (amagi), or “liberty.” It is taken from a clay document written about 2300 B.C. in the Sumerian city-state of Lagash, in present day Iraq. To find out more about Liberty Fund, Inc., or the Online Library of Liberty Project, please contact the Director at [email protected]. -

Matthew Parker and His Scribes

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 12-2016 Old English Manuscripts in the Early Age of Print: Matthew Parker and his Scribes Robert Scott Bevill University of Tennessee, Knoxville, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss Part of the Book and Paper Commons, Intellectual History Commons, Literature in English, British Isles Commons, Medieval History Commons, and the Medieval Studies Commons Recommended Citation Bevill, Robert Scott, "Old English Manuscripts in the Early Age of Print: Matthew Parker and his Scribes. " PhD diss., University of Tennessee, 2016. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss/4084 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by Robert Scott Bevill entitled "Old English Manuscripts in the Early Age of Print: Matthew Parker and his Scribes." I have examined the final electronic copy of this dissertation for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, with a major in English. Roy M. Liuzza, Major Professor We have read this dissertation and recommend its acceptance: Thomas J. Heffernan, Maura K. Lafferty, Anthony Welch Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. Hodges Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) Old English Manuscripts in the Early Age of Print: Matthew Parker and his Scribes A Dissertation Presented for the Doctor of Philosophy Degree The University of Tennessee, Knoxville Robert Scott Bevill December 2016 ii Copyright © by Robert Scott Bevill All rights reserved. -

William Camden and the Re-Discovery of England R.C

William Camden and the Re-Discovery of England R.C. Richardson William Camden (1551–1623) stands out as one of the founding fathers of English Local History, with Britannia (1586) his chief claim to fame. This article takes stock of the remarkable shelf life of this classic book, its aims, methodology, structure and achievement. Camden’s account of Leicestershire receives special attention. By virtue of its agenda, Britannia needs to be seen as a work of national re-discovery, while its enthusiastic reception by the author’s contemporaries demonstrates how much it contributed to the defining and development of ‘Englishness’ in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries. The late sixteenth century in England stands out as one of the most remarkable periods in this country’s history and witnessed enormous and often unsettling and destabilising social, economic, cultural, religious and political changes as well as outstanding achievements in many fields. A huge outpouring of creative cultural energy occurred. Shakespeare, Ralegh, Sidney, Spenser and many more of their contemporaries are justly celebrated; the roll-call is stunningly impressive. William Camden, by contrast, did not become a household name either at that time or since. Even Thomas Fuller’s mid seventeenth-century The Worthies of England curiously omits him. His life was, by most standards, unspectacular and uneventful. Yet, within the scholarly circle in which he moved during his lifetime his reputation was very considerable. His tomb which is in Westminster Abbey, close to that of Chaucer, bears the inscription, ‘Camden, the Nurse of antiquity and the lantern unto succeeding ages’.1 A glowing biography of him in Latin by Thomas Smith was published in 1691. -

From the Romans to the Normans on the English Renaissance Stage

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Early Drama, Art, and Music Medieval Institute Publications 11-30-2017 From the Romans to the Normans on the English Renaissance Stage Lisa Hopkins Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/mip_edam Part of the Dramatic Literature, Criticism and Theory Commons, and the Theatre History Commons Recommended Citation Hopkins, Lisa, "From the Romans to the Normans on the English Renaissance Stage" (2017). Early Drama, Art, and Music. 3. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/mip_edam/3 This Monograph is brought to you for free and open access by the Medieval Institute Publications at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Early Drama, Art, and Music by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact wmu- [email protected]. From the Romans to the Normans on the English Renaissance Stage Lisa Hopkins EARLY DRAMA, ART, AND MUSIC From the Romans to the Normans on the English Renaissance Stage EARLY DRAMA, ART, AND MUSIC Series Editors David Bevington University of Chicago Robert Clark Kansas State University Jesse Hurlbut Brigham Young University Alexandra Johnston University of Toronto Veronique B. Plesch Colby College ME Medieval Institute Publications is a program of The Medieval Institute, College of Arts and Sciences From the Romans to the Normans on the English Renaissance Stage by Lisa Hopkins Early Drama, Art, and Music MedievaL InsTITUTE PUBLICATIOns Western Michigan University Kalamazoo Copyright © 2017 by the Board of Trustees of Western Michigan University Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data are available from the Library of Congress. -

The Elizabethan Society of Antiquaries Reassessed

THE ELIZABETHAN SOCIETY OF ANTIQUARIES REASSESSED By HELEN DOROTHY JONES A. (Hons.), The University of British Columbia, 138 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN HISTORY i n THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES (Department of Hi story> We accept this thesis as conforming bo the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA August, 1988 (c) Helen Dorothy Jones, 1988 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the head of my department or by his or her representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department of b«? p The University of British Columbia 1956 Main Mall Vancouver, Canada V6T 1Y3 Date IV-^i^b 3^2.///CjrJTff- DE-6G/81) i i ABSTRACT The Elizabethan Society of Antiquaries has traditionally been regarded as a scholarly group which dissolved due to attrition and perhaps the suspicion of the ruling administration. A 1614 effort to recongregate failed due to James I's'unfounded suspicions of the members' political intentions. This interpretation rests on the assumption that the discourses produced by members were the object of the Society, and that the members were primarily scholars. While the discourses required extensive research, they were superficial and uncritical, not representative of the standard of historical work of which some of the members, such as Camden, Stow and Lambarde, were capable.