Praying Mantis: a Unique Glen Meyer Village in London

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2019 Development Charges Background Study Page 2 TABLE of CONTENTS

2019 Development Charges Background Study DEVELOPMENT FINANCE DRAFT February 25, 2019 TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER 1: EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ...................................................................... 4 CHAPTER 4: CALCULATION OF THE DEVELOPMENT CHARGE RATE ............. 16 CHAPTER 2: BACKGROUND STUDY PURPOSE & PROCESS .............................. 7 4.1 Planning Period 4.2 Growth Forecasts 2.1 Purpose of the Development Charge Background Study 4.3 Forecasting Future Capital Needs 2.2 2019 Development Charge Process 4.4 Legislated Adjustments to Arrive at Net DC Eligible Amount 2.2.1 DC External Stakeholder Committee 4.5 Examination of Existing Levels of Service 2.2.2 Policy Decisions 4.6 Calculating DC Rates 2.2.3 Growth Forecasts TABLE 4-1: Proposed Development Charge Rates 2.2.4 Servicing Needs and DC Master Plans 2.2.5 Draft Rate Calculations CHAPTER 5: SUMMARIES OF THE DEVELOPMENT CHARGE RATES ............... 21 2.2.6 Council Review and Public Input Process TABLE 5-1: All Services CHAPTER 3: DEVELOPMENT CHARGES ACT & POLICIES ................................ 10 TABLE 5-2: Residential 3.1 Amendments to the Development Charges Act, 1997 – Bill 73 TABLE 5-3: Non-Residential 3.1.1 Area Rating TABLE 5-4: Timing of Expenditures 3.1.2 Asset Management Plan for New Infrastructure 3.1.3 60 Day Circulation Period for DC Background Study APPENDIX A: Growth Forecasts ........................................................................... 26 3.1.4 Timing of DC Collection 3.1.5 Transit TABLE A-1: Employment 3.1.6 Changes to Ineligible Services -

Guest Speakers 2012 Fanshawe College Spring Convocation

GUEST SPEAKERS 2012 FANSHAWE COLLEGE SPRING CONVOCATION Christopher Hood Program Director, Boys’ and Girls’ Club of London June 12 at 10 a.m. Christopher was born and raised in Toronto and is a graduate of Western University. His love of sports led him into teaching at the elementary level for the Toronto Board of Education, and at Variety Village, where he taught adapted Physical Education to physically and mentally challenged children. He also coached wheelchair basketball, wheelchair tennis, wheelchair track and field and sledge hockey at the national and international levels. Christopher returned to London four years ago to work at the Boys’ and Girls’ Club of London, where he started My Action Plan to Education (M.A.P.) as the program manager. M.A.P. provides academic support (after school tutoring), advocacy (connected to the school boards), social support (with leadership and mentoring), and financial scholarship for post-secondary education. There are currently 11 M.A.P. graduates studying at Fanshawe. Christopher has also coached and trained professional athletes from the CFL, NHL, and CIS, as well as Olympic athletes and triathletes in Iron Man triathlons. His hobbies include cycling, surfing and gourmet popcorn! Danielle Aziz Director and Group Facilitator, Onward Social Skills June 12 at 2 p.m. A graduate of Fanshawe College’s Child and Youth Worker (CYW) program, Danielle began her career as a counselor, teaching anger management techniques to boys and girls who had been diagnosed with ADHD. Based on those experiences, she created Onward Social Skills in 1996 as a resource to help children face difficult emotions, learn to make friends, and develop basic social skills. -

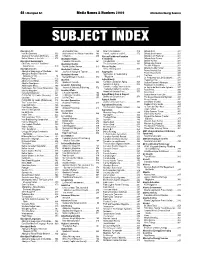

Subject Index

48 / Aboriginal Art Media Names & Numbers 2009 Alternative Energy Sources SUBJECT INDEX Aboriginal Art Anishinabek News . 188 New Internationalist . 318 Ontario Beef . 321 Inuit Art Quarterly . 302 Batchewana First Nation Newsletter. 189 Travail, capital et société . 372 Ontario Beef Farmer. 321 Journal of Canadian Art History. 371 Chiiwetin . 219 African/Caribbean-Canadian Ontario Corn Producer. 321 Native Women in the Arts . 373 Aboriginal Rights Community Ontario Dairy Farmer . 321 Aboriginal Governments Canadian Dimension . 261 Canada Extra . 191 Ontario Farmer . 321 Chieftain: Journal of Traditional Aboriginal Studies The Caribbean Camera . 192 Ontario Hog Farmer . 321 Governance . 370 Native Studies Review . 373 African Studies The Milk Producer . 322 Ontario Poultry Farmer. 322 Aboriginal Issues Aboriginal Tourism Africa: Missing voice. 365 Peace Country Sun . 326 Aboriginal Languages of Manitoba . 184 Journal of Aboriginal Tourism . 303 Aggregates Prairie Hog Country . 330 Aboriginal Peoples Television Aggregates & Roadbuilding Aboriginal Women Pro-Farm . 331 Network (APTN) . 74 Native Women in the Arts . 373 Magazine . 246 Aboriginal Times . 172 Le Producteur de Lait Québecois . 331 Abortion Aging/Elderly Producteur Plus . 331 Alberta Native News. 172 Canadian Journal on Aging . 369 Alberta Sweetgrass. 172 Spartacist Canada . 343 Québec Farmers’ Advocate . 333 Academic Publishing Geriatrics & Aging. 292 Regional Country News . 335 Anishinabek News . 188 Geriatrics Today: Journal of the Batchewana First Nation Newsletter. 189 Journal of Scholarly Publishing . 372 La Revue de Machinerie Agricole . 337 Canadian Geriatrics Society . 371 Rural Roots . 338 Blackfly Magazine. 255 Acadian Affairs Journal of Geriatric Care . 371 Canadian Dimension . 261 L’Acadie Nouvelle. 162 Rural Voice . 338 Aging/Elderly Care & Support CHFG-FM, 101.1 mHz (Chisasibi). -

City of London Register of Cultural Heritage Resources

City of London Register of Cultural Heritage Resources City Planning 206 Dundas Street London, Ontario N6A 1G7 Last Updated: July 2, 2019 Register of Cultural Heritage Resources Register Introduction The City of London’s Register is provided by the City for information The Register is an essential resource used by the public and City staff to purposes only. The City of London endeavours to keep the Register current, identify the cultural heritage status of properties in the City of London. The accurate, and complete; however, the City reserves the right to change or first City Council-adopted Inventory of Heritage Resources was created in modify the Register and information contained within the Register at any time 1991, and was compiled from previous inventories dating back to the 1970s. without notice. The Inventory of Heritage Resources was reviewed and revised in 1997 to include newly-annexed areas of the City of London. In 2005-2006, City For information on a property’s cultural heritage status, please contact a Council adopted the revised Inventory of Heritage Resources. The Inventory Heritage Planner at 519-661-4890 or [email protected]. of Heritage Resources (2006) was adopted in its entirety as the Register pursuant to Section 27 of the Ontario Heritage Act on March 26, 2007. Since The cultural heritage status of properties can also be identified using CityMap, 2007, City Council has removed and added properties to the Register by www.maps.london.ca. resolution. To obtain an extract of the Register pursuant to Section 27(1) of the Ontario The Register includes heritage listed properties (Section 27 of the Ontario Heritage Act, please contact the City Clerk. -

Master Works Cited Archer, Michael. Art Since 1960

Master Works Cited Archer, Michael. Art Since 1960. London: Thames and Hudson Ltd, 1997. Baker, Michael, and Hilary Bates Nealy. 100 Fascinating Londoners. Toronto: James Lorimer and Co. Ltd., 2005. Belanger, Joe. “Former Library Sold to Farhi for $2.4M.” The London Free Press, 18 May 2005. Canadian Artists Representation/Le Front des artistes canadiens (CARFAC). “CARFAC History.” CARFAC website, http://www.carfac.ca/about/history/, Accessed 13 March, 2009. ---. “What is CARFAC?” CARFAC website, http://www.carfac.ca/index-en.php, Accessed 14 March 2009. ---. “Regional Branches.” CARFAC website, http://www.carfac.ca/about/regional-branches, Accessed 13 March, 2009 ---. “What is CARFAC?.” CARFAC website, http://www.carfac.ca/about/about-carfac-a-propos-de- carfac/, Accessed 13 March, 2009 CCCA. “Artist's Curriculum Vitae.” Centre for Contemporary Canadian Art website, http://ccca.finearts.yorku.ca/cv/english/chambers-cv.html, Accessed 9 March 2009. Chambers, Jack. [1978] Jack Chambers. London, ON: [Nancy Poole]. Limited edition autobiography available in Archives and Research Collections Centre (ARCC) of The University of Western Ontario. Chandler, John Noel. “Redinger and Zelenak: A note.” artscanada, 26 no. 2 (April 1969), 23. ---. “Sources are Resources: Greg Curnoe's Objects, Objectives and Objections.” artscanada. 176, February – March 1973, 23-5. Company Histories. “Labatt Brewing Company Limited.” Company Histories, http://www.answers.com/topic/labatt-brewing-company, Accessed 20 December 2008. Colbert, Judith. London Regional Art Gallery – A Profile. London (Ont.): Volunteer Committee to the London Regional Art Gallery, 1981. Curnoe, Greg. “Five Co-op Galleries in Toronto and London from 1957 – 1992.” Unpublished notes, Greg Curnoe artist file, McIntosh Gallery, UWO, 1992. -

The Musical Museum London Justin Hines 2 October, 2011 3

Issue 25 October 2011 1 Evil Dead: The Musical Museum London Justin Hines 2 October, 2011 3 contents theatre October 2011 4 From the Editor Richard Young – A bigger and better Beat 6 On Stage Sarah Needles – Evil Dead splatters onto McManus Stage 8 Spotlight Jill Ellis – Th e art of micropigmentation Bringing Music to Life! 10 Film Chris Loblaw – London Short Film Showcase 1212 Visual Arts Beth Stewart – Glad tidings and complex vision 1414 Q & A Carol McLeod – With Justin Hines music BEATLES RUBBER SOUL & REVOLVER 16 News & Views Phil McLeod – Th e fi ve minute rule Red HoHot WWeeekekenendsds 1818 News & Views Paula Schuck – Museum London in the hot seat n October 14 & 15 - 8pm / Centennial Hall 2020 Words Ruth McGregor– Starting Your Career as an Artist nna 22 Feature Susan Scott – Art in the city Bre OrO chc estra LoL nddonn & Thehe Jeeaans ‘n Clasa sicss Band pressennttss thhe 2424 Spotlight Art Fidler – What the arts mean to Dale Hunter er Beatles beauauƟfulu ly acoouussƟc-flavooured Ruubbbeer Soul followeed Photo Tribute Pet by very progresssivve RReevvolvveer in its ennƟrety. 26 Richard Young – Th ank you to Paul Miszczyk 28 Health Track Lisa Shackelton & David Fife – Eat Well, Live Well artsvisual festivals 30 Sound Bites Bob Klanac – John Bellone’s:All in the family CLASSICAL, WITH A PASSION! Cathedraal 34 Classical Beat Nicole Laidler – A chamber of delight October 19 - 8pm / St. Paul’s Cathedral 3838 Art on the Arts Art Fidler – Fight the funk Pegg’s World lin Haydn’s ppaasssionatee TTrraauuere Sympphony highlights this 40 Robert Pegg – What Wave Dave – the heppest cat in town ank 4242 Final Frame London through the lens of Deborah Zuskan Fr “sstormmyy” prorogrraam of woorkr s. -

2ND REPORT of the CREATIVE CITY COMMITTEE Meeting Held On

2ND REPORT OF THE CREATIVE CITY COMMITTEE Meeting held on August 23, 2007, commencing at 12:15 p.m. PRESENT: Controller G. Hume (Chair), Mayor A. M. DeCicco-Best, Controller G. Barber, Councillors J. L. Baechler, H. L. Usher and D. Winninger and H. Lysynski (Secretary). ALSO PRESENT: Councillors J. Bryant and B. MacDonald, R. Armistead, T. Johnson and J. Walters. I YOUR COMMITTEE RECOMMENDS: Creative City 1. That the following requests for funding under the Creative City Fund Funding . Applications BE APPROVED: (a) London Heritage Council for start up funding in the amount of $23,000; (b) Mainstreet London for the Mural Project in the amount of $5,000; (c) A. Francis for London Ontario Live Arts (LOLA) in the amount of $6,000; and, (d) London Reads in the amount of $2,000; it being noted that the funding applications and a summary chart of the funding allocations for 2007 are attached; it being further noted that verbal presentations were heard from A. Cohen, T. Aitken, J. Manness, B. Meehan, London Heritage Council; S. Curtis-Norcross and K. Mclaughlin, Mainstreet London and the London Downtown Business Association; and A. Francis, London Ontario Live Arts, with respect to this matter. Non-Voting 2. (4,22) That the following individuals BE APPOINTED to the Creative City Resource Members Committee as.Non-Voting Resource Members in the following categories: Arts -A. Halwa Business District Revitalization - S. Merritt Diversity - R. Muiioz-Castiblanco Economic Development - C. Kehoe Emerging Leaders - K. Wiggett Environment - B. Benedict Heritage -A. Kennedy Housing - J. Binder Libraries - L. Sage Tourism and Conventions - D. -

City of London's Celebrate

Agenda Item # Page # 1 TO: CHAIR AND MEMBERS BOARD OF CONTROL MEETING ON JANUARY 18,2006 FROM: COUNCILLOR JON1 BAECHLER CHAIR - CELEBRATE 150 SUBJECT: CELEBRATE 150 FINAL REPORT II RECOMMENDATIONS II That, on the recommendation of Councillor Joni Baechler, Chair of the Celebrate 150 initiative, the following actions BE TAKEN: (a) The Mayor FORMALLY ACKNOWLEDGE the tremendous contributions of the Celebrate 150 Committee volunteers and event organizers who made our sesquicentennial celebrations so successful. (b) The remaining unused funds estimated to be in between eight and ten thousand dollars BE USED to purchase, or as a contribution toward the purchasing of a piece of public art as a public remembrance of the Londoners who have contributed and continue to contribute to this great city on a daily basis. PREVIOUS REPORTS PERTINENT TO THIS MATTER Administration Report concerning the framework for the 150thAnniversary of the City's incorporation (July 28, 2004). Board of Control Report with revisions adopted by Council. Authorizing Administration to proceed with planning activities for the anniversary year. (September 1, 2004). Information report by the Celebrate 150 Chair outlining the Steering committee structure (November, 2004). Board of Control Report - Chair of the Celebrate 150 Steering Committee Recommendations and Plan. (December 1,2004). I BACKGROUND Council at its meeting held on December 1, 2004 approved the following recommendation: That, on the recommendation of the Chairof the Celebrate 150 Steering Committee, the following -

Annual Report 12

ANNUAL REPORT 2013 THE MUSEUM 2013 Samantha Roberts volunteers her time in our library archives. Happy visitors tour the exhibition L.O. Today during the opening reception. 2013 was a year of transition and new growth for London, our tour guides, board and committee Museum London. As we entered 2013, we were members, Museum Underground volunteers, and guided by our new Strategic Plan, which had the many others—who have done exceptional work to succinct focus of attracting “Feet, Friends, and support the Museum this past year and over the Funds” and achieving the goals of creating many years of the Museum's history. opportunities for dialogue—about art and history, about our community, and indeed, about our 2013 also saw us transition our membership organization through a wide variety of program into a “supporters” program that has experiences and opportunities for engagement. enabled the Museum to engage and connect with a much larger segment of our community. All We also embarked on a new model of volunteerism Londoners are now able to enjoy the benefits of that provided new and diverse opportunities for a participating in and supporting the Museum. The wide variety of people interested in supporting art continued commitment of our supporters has and heritage in the community. The reason for our enabled us to maintain Museum London as an renewed approach is the changing face of important cultural institution with a national volunteerism: today young people volunteer to reputation for excellence. support their professional and educational goals, new Canadians volunteer as a way to connect with The City of London chose to create a separate their new home and with potential employers, and board to manage Eldon House beginning January seniors offer up their years of experience and 1, 2013. -

Vividata Brands by Category

Brand List 1 Table of Contents Television 3-9 Radio/Audio 9-13 Internet 13 Websites/Apps 13-15 Digital Devices/Mobile Phone 15-16 Visit to Union Station, Yonge Dundas 16 Finance 16-20 Personal Care, Health & Beauty Aids 20-28 Cosmetics, Women’s Products 29-30 Automotive 31-35 Travel, Uber, NFL 36-39 Leisure, Restaurants, lotteries 39-41 Real Estate, Home Improvements 41-43 Apparel, Shopping, Retail 43-47 Home Electronics (Video Game Systems & Batteries) 47-48 Groceries 48-54 Candy, Snacks 54-59 Beverages 60-61 Alcohol 61-67 HH Products, Pets 67-70 Children’s Products 70 Note: ($) – These brands are available for analysis at an additional cost. 2 TELEVISION – “Paid” • Extreme Sports Service Provider “$” • Figure Skating • Bell TV • CFL Football-Regular Season • Bell Fibe • CFL Football-Playoffs • Bell Satellite TV • NFL Football-Regular Season • Cogeco • NFL Football-Playoffs • Eastlink • Golf • Rogers • Minor Hockey League • Shaw Cable • NHL Hockey-Regular Season • Shaw Direct • NHL Hockey-Playoffs • TELUS • Mixed Martial Arts • Videotron • Poker • Other (e.g. Netflix, CraveTV, etc.) • Rugby Online Viewing (TV/Video) “$” • Skiing/Ski-Jumping/Snowboarding • Crave TV • Soccer-European • Illico • Soccer-Major League • iTunes/Apple TV • Tennis • Netflix • Wrestling-Professional • TV/Video on Demand Binge Watching • YouTube TV Channels - English • Vimeo • ABC Spark TELEVISION – “Unpaid” • Action Sports Type Watched In Season • Animal Planet • Auto Racing-NASCAR Races • BBC Canada • Auto Racing-Formula 1 Races • BNN Business News Network • Auto -

CURRICULUM VITAE JODY CULHAM Brain and Mind Institute Western Interdisciplinary Research Building 4118 Western University London, Ontario Canada N6A 5B7

November 11, 2020 CURRICULUM VITAE JODY CULHAM Brain and Mind Institute Western Interdisciplinary Research Building 4118 Western University London, Ontario Canada N6A 5B7 Office: 1-(519)-661-3979 E-mail: [email protected] World Wide Web: http://www.culhamlab.com/ Citizenship: Canadian ACADEMIC CAREER Department of Psychology Western University (formerly University of Western Ontario) Professor, July 2013 – present Visiting Professor and Academic Nomad (Sabbatical): Centre for Mind/Brain Sciences, University of Trento, Italy (September 2015-February 2016); Scuola Internazionale Superiore di Studi Avanzati (SISSA), Trieste, Italy (March-April 2016); Centre for Functional MRI of the Brain (FMRIB), Oxford University, UK (May 2016); University of Coimbra, Portugal (June 2016); Philipps University Marburg and Justus Liebig University Giessen (July 2016), Tokyo Institute of Technology (August 2016). Associate Professor, July 2007 – June 2013 Visiting Associate Professor (Sabbatical), Department of Cognitive Neuroscience, University of Maastricht, Netherlands (September-December 2008) and Department of Physiology and Residence of Higher Studies, University of Bologna, Italy (January-May 2009) Assistant Professor, July 2001 – June 2007 Affiliations: Brain and Mind Institute; Graduate Program in Neuroscience; Canadian Action and Perception Network Awards: Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council (Canada) E. W. R. Steacie Memorial Fellowship, June 2010 Senior Fellowship, University of Bologna, January-March 2009 Western Faculty Scholar Award, March 2008 Western Faculty of Medicine Dean’s Award for Excellence in Research in the Team category, CIHR Group on Action and Perception, 2007 Canadian Institutes of Health Research New Investigator Award, 2003 Ontario Premier’s Research Excellence Award, 2003 McDonnell-Pew Postdoctoral Fellow Western University May 1997 - June 2001 Advisor: Dr. -

Annual Report 2016 2016 Annual Report

ANNUAL REPORT 2016 2016 ANNUAL REPORT A REPORT FROM THE BOARD OF DIRECTORS This year Museum London celebrated its 36th year at the Forks of the Thames with the launch of a project that we think will redefine our place at the Forks. Our Centre at the Forks project will engage Londoners and visitors alike by delivering innovation in Museum design and programming while contributing to the revitalization of the Forks of the Thames. The Centre at the Forks will also showcase an expansive, panoramic two-story window and an outdoor terrace, linking Museum London and the Forks of the Thames in a dynamic new relationship at the historic heart of London. Design work and fundraising began in 2016, construction begins in 2017, and we anticipate completion in early 2018. 2016 was also another strong year for providing our community with an outstanding array of art exhibitions including The Desire to Acquire, a look at the numerous public and private art collections in London, Chronologues, a group exhibition of contemporary art examines issues of memory and time, through personal narratives and larger, shared histories, and A Ripple Effect: Canadians and Fresh Water which examined the story of Canadians’ relationship with fresh water by focusing on the Thames, Speed, and Eramosa rivers. Other exhibitions included Akram Zaatari: Tomorrow Everything will be Alright, the first Canadian solo exhibition of celebrated Lebanese artist Akram Zaatari, TransAMERICAS: a sign, a situation, a concept, an exhibition of Latin American artists addressing themes of community, travel, and language, as well as Cursive! Reading and Writing the Old School Way, and Out with the Old? Creating a ‘Throw-Away’ Society All these exhibitions were complemented by an impressive program schedule that included artist talks, films exploring the themes highlighted in the exhibitions, as well as stand-alone projects on topics of interest to the community.