Strange but True, Part 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fats Domino Goin' Home

“Goin’ Home” We’ll Miss You, Fats “Everybody started calling my music rock and roll, but it wasn't anything but the same rhythm and blues I'd been playing down in New Orleans.” - FATS DOMINO “As far as I know, the music makes people happy. I know it makes me happy.” - FATS DOMINO “Let's face it, I can't sing like Fats Domino can. I know that.” - ELVIS PRESLEY “Well, I wouldn't want to say that I started it (rock „n‟ roll), but I don't remember anyone else before me playing that kind of stuff.” - FATS DOMINO “Even if Fats didn‟t actually invent rock „n‟ roll, he was certainly responsible for accidentally inventing ska, and thus reggae … Antoine „Fats‟ Domino was definitely a great innovator, and richly deserves a much fatter entry in the history books.” – OWEN ADAMS On Tuesday, 3:30 a.m., October 24, 2017, New Orleans and the world lost a pioneering titan of rock „n‟ roll, “Fats” Domino. The popular pianist and singer-songwriter of the Lower 9th Ward was 89. During his career, this influential, yet humble performer sold more than 65 million records and had over 35 hits in the U.S. Billboard Top 40, including “Ain‟t That a Shame,” “Blueberry Hill” and “Blue Monday”. With producer and arranger Dave Bartholomew, “Fats” helped put his hometown on the rock „n‟ roll map. This shy lifelong New Orleanian influenced numerous artists including Paul McCartney and Randy Newman, who once confessed, “I was so influenced by Fats Domino that it‟s still hard for me to write a song that‟s not a New Orleans shuffle.” Domino‟s distinctive barreling triplet-based piano style, backed by a solid backbeat, was something exceptional, a step above traditional rhythm and blues. -

Wavelength (November 1984)

University of New Orleans ScholarWorks@UNO Wavelength Midlo Center for New Orleans Studies 11-1984 Wavelength (November 1984) Connie Atkinson University of New Orleans Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uno.edu/wavelength Recommended Citation Wavelength (November 1984) 49 https://scholarworks.uno.edu/wavelength/49 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Midlo Center for New Orleans Studies at ScholarWorks@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Wavelength by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. I I ~N0 . 49 n N<MMBER · 1984 ...) ;.~ ·........ , 'I ~- . '· .... ,, . ----' . ~ ~'.J ··~... ..... 1be First Song • t "•·..· ofRock W, Roll • The Singer .: ~~-4 • The Songwriter The Band ,. · ... r tucp c .once,.ts PROUDLY PR·ESENTS ••••••••• • • • • • • • •• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • ••••••••• • • • • • • • •• • • • • • • • • • • • • • •• • • • • • • • • • • • ••••••••••• • •• • • • • • • • ••• •• • • • • • •• •• • •• • • • •• ••• •• • • •• •••• ••• •• ••••••••••• •••••••••••• • • • •••• • ••••••••••••••• • • • • • ••• • •••••••••••••••• •••••• •••••••• •••••• •• ••••••••••••••• •••••••• •••• .• .••••••••••••••••••:·.···············•·····•••·• ·!'··············:·••• •••••••••••• • • • • • • • ...........• • ••••••••••••• .....•••••••••••••••·.········:· • ·.·········· .....·.·········· ..............••••••••••••••••·.·········· ............ '!.·······•.:..• ... :-=~=···· ····:·:·• • •• • •• • • • •• • • • • • •••••• • • • •• • -

Fats Domino, Early Rock 'N' Roller with a Boogie-Woogie Piano, Is Dead at 89

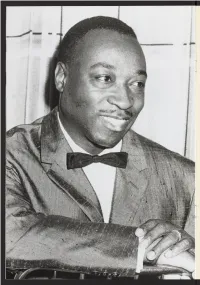

Fats Domino, Early Rock ’n’ Roller With a Boogie-Woogie Piano, Is Dead at 89 https://www.nytimes.com/2017/10/25/obituaries/fats-domino-89-one-of-rock-n-rolls-first-stars-is-dead.html October 25, 2017 By JON PARELES and WILLIAM GRIMES Fats Domino in 1967. Fats Domino, the New Orleans rhythm-and-blues singer whose two-fisted boogie-woogie piano and nonchalant vocals, heard on dozens of hits, made him one of the biggest stars of the early rock ’n’ roll era, died on Tuesday at his home in Harvey, La., across the Mississippi River from New Orleans. He was 89. His death was confirmed by the Jefferson Parish coroner’s office. Mr. Domino had more than three dozen Top 40 pop hits through the 1950s and early ’60s, among them “Blueberry Hill,” “Ain’t It a Shame” (also known as “Ain’t That a Shame,” which is the actual lyric), “I’m Walkin’,” “Blue !1 Monday” and “Walkin’ to New Orleans.” Throughout he displayed both the buoyant spirit of New Orleans, his hometown, and a droll resilience that reached listeners worldwide. He sold 65 million singles in those years, with 23 gold records, making him second only to Elvis Presley as a commercial force. Presley acknowledged Mr. Domino as a predecessor. “A lot of people seem to think I started this business,” Presley told Jet magazine in 1957. “But rock ’n’ roll was here a long time before I came along. Nobody can sing that music like colored people. Let’s face it: I can’t sing it like Fats Domino can. -

History & Tradition All-Time Letterwinners

history & tradition all-time letterwinners Since 1947 Warren Belin 1987-90 Dwayne Crayton 1977-80 Nick Belisis 1948-49 • c • Mark Cregar 1974-77 • e • Nick Bender 1997-2000 Bob Caesar 1955-56 Ward Cridland 1979 Paul Eberle 1978-80 • a • Doug Benfield 1973-75 Jimmy Caldwell 1998-2000 Derek Crocker 1979-80 John Eck 1981 Greg Adkins 2002 Terry Bennett 1970-71 Richard Cameron 1962-64 Dan Croom 1973 Farrell Egge 1961-62 Mark Agientas 1987-88 Tim Bennett 1999-02 Jim Camp 1945-46 Matt Crosby 1990-91 Mike Elkins 1985-88 Steven Ainsworth 1989-91 Brad Benson 1987-89 Edward Campbell 1972 Claude Croston 1954-55 Greg Eller 1982 Chad Alexander 1995,97 Steve Bernardo 1976-77 Glen Campbell 1984 Austin Crowder 1992-95 Tom Elrod 1996 Boyd Allen 1946-47 Joe Berra 1963-65 Tommy Campbell 1970 Ron Crume 1983 Ken Erickson 1966,68-69 Bob Allen 1958-60 Cornelius Birgs 2002 Mike Capone 1971 Carlos Cunningham 1979-82 Urban Ericksson 1976 Lee Allen 1972-74 Carroll Blackerby 1948-50 Bernie Capps 1945-46 Aubrey Currie 1956-58 George Ervin 1976-79 Tom Allen 1999 Terry Blanch 1978-79 Joe Carazo 1963-65 Carl Curry 1974-76 Marlon Estes 1992-93,95 Ryan Alston 1991-92 Rhett Blanchard 1991-94 Bill Carlisle 1961-62 Marlon Curtis 1998-99 Solomon Everett 1974-76 Louis Altobelli 1986,88-89 James Bland 1952-53 Andy Carlton 1972-73 Dominic Anderson 2002 Chris Blank 1997-2000 Frank Carmines 1985-86 • f • Jason Anderson 2001-02 Mike Blasiole 1967 Charlie Carpenter 1955-57 Mark Anderson 1975 Bill Bobbora 1969-71 Tehran Carpenter 1998-2000 Wilbert Faircloth 1962-63 Tom Anderson 1972 -

Additions and Corrections in the 15 Months Since Publishing RTRW, I've

Additions and Corrections In the 15 months since publishing RTRW, I’ve had a chance to dig deeper and refine some of the writer data as well as a number of typos and minor corrections. This document includes all the corrections I’ve found, big and small. A number of song attributions should also be updated to include “Traditional” as they are based on traditional melodies but were uncredited as such in the royalty or copyright citations. In some cases, additional attribution is called for due to apparent copyright and rights theft and in some cases inadvertent borrowing of music or lyric. There are a few I just missed. I Dig Girls by J.J. Jackson was written by Edmond Windsor King, who I initially conflated with Ed King of Strawberry Alarm Clock and Lynyrd Skynyrd fame. He is now Windsor King. Predecessor songs to “Going Up The Country” and “Grizzly Bear” were also found and authors of those predecessors were given credit. I was put onto the most interesting example by Rich Appel. I credited My Ding-A-Ling to Chuck Berry because the rights, label and copyright only credited him. Rich pointed out there was a 1952 song called My Ding-A-Ling recorded by Dave Bartholomew that had an uncanny resemblance to the Chuck Berry song, and he was right. Rights, label and copyright assign this song to Dave Bartholomew and Sam Rhodes. The lyrics are a bit different between the two songs but the joke is the same. But there’s more history. Chuck Berry had a song called My Tambourine on his 1968 album From St. -

Evolutionary Ideas

NEW ORLEANS NOSTALGIA Remembering New Orleans History, Culture and Traditions By Ned Hémard Evolutionary Ideas English Naturalist Charles Darwin (1809-1882) published his famous theory in his 1859 book On the Origin of Species, a relatively recent archetype of an evolutionary worldview going back to Ancient Greece. Greek philosophers such as Anaximander of Miletus had previously postulated the development of life from non-life and the evolutionary descent of man from animal. Taking into account the presence of fossils, Anaximander claimed that animals sprang out of the sea eons ago. The early humidity eventually evaporated, dry land emerged and, in time, adaptations occurred. Darwin simply brought something new to these old ideas (an explanatory mechanism called “natural selection”, which accumulates and preserves minor advantageous genetic mutations. Through the years, New Orleanians (as well as others around the world) have taken their stabs at commenting on (or satiring) Darwin’s Theory of Evolution. Nobody likes to be made out to be a monkey, but in this 1871 caricature published in The Hornet, a satirical magazine, Darwin is pictured as “A Venerable Orang-outang”. Darwin had something very much in common with another famous person, Abraham Lincoln. First, they were both born on the very same day, February 12, 1809. Secondly, they were both ridiculed as primates. Lincoln was called “The Ape Baboon of the Prairie”; and, in an 1861 letter to his wife, General George B. McClellan called Lincoln “the original gorilla”. After the Emancipation Proclamation, cartoons like the one below depicted Lincoln as some type of a simian-like creature, delivering his document to the people. -

Dave Bartholemew 1991.Pdf

NON-PERFORMERS Dave Bartholomew BY JEFF TAMARKIN E NEVER MADE THE POP charts under his own name. Most rock encyclopedias afford him, at most, a paragraph or two. But as an artist, producer, songwriter, arranger, and bandleader, Dave Bartholomew of New Orleans was a key figure in the transition from the jivin’ jump and big-band sounds of the ’40s to the rhythm & blues and rock & roll of the ’50s. “If Dave Bartholomew were never to play another note,” Walkin’.” Nor was Bartholomew’s hot streak confined to his wrote New Orleans music historian Jeff Hannusch in I H ear work with a single artist or record label. Freelancing for such You K nockin’, “he could sit back and bask in the knowledge labels as Aladdin and Specialty, he produced Lloyd Price’s that he was very much responsible for shaping today’s mu “Lawdy Miss Clawdy” and Shirley & Lee’s “I’m Gone” in sic.” 1952. For Smiley Lewis, he co-wrote and produced “I Hear Dave Bartholomew’s name is permanently linked with You Knocking” and “One Night.” New Orleans artists Earl that of Hall of Fame charter inductee Fats Domino— he pro King, Roy Brown, Huey “Piano” Smith, Bobby Mitchell, Chris duced all of the Fat Man’s Imperial hits Kenner, Robert Parker, Frankie Ford, and co-wrote most of them. But Dave’s JU ST SOME Snooks Eaglin, and the Spiders all ben career was already in full swing when OF THE SONGS OF efited from Bartholomew’s hummable, he first spotted Domino at New Or DAVE BARTHOLOMEW good-time melodies and simple, sturdy leans’ Hideaway Club in December, rhythms 1949. -

The Golden Age of Rock 'N' Roll

The Golden Age of Rock ’n’ Roll Week 5, March 19, 2018 1956 (part 2): Elvis, Fats, Little Richard Assignment: “The Story of Blue Suede Shoes” http://www.rebeatmag.com/carl-perkins-elvis-blue-suede-shoes-story/ Rolling Stone: “The Rope: The Forgotten History of Segregated Rock & Roll Concerts” http://www.rollingstone.com/music/features/rocks-early-segregated-days-the- forgotten-history-w509481 Little Richard profile with rare photos: http://www.history-of-rock.com/richard.htm Listen to: Church Bells May Ring, The Willows, 1956 (#62 Pop, #12 R&B) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tLl1eDAWMeA [optional] Compare: The Diamonds, 1956 (#14 Pop) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IdBN-hOmtVE Fever, Little Willie John, 1956 (#1 R&B) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=i93-hlwULUk [optional] Compare: Peggy Lee, 1956 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Kjy2sZ8yBGQ Be-Bop-A-Lula, Gene Vincent, 1956 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=O4_5593-skQ Page !1 Oh What a Night, The Dells, 1956 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Z1ozQT8yQXA I Walk the Line, Johnny Cash, 1956 (#1 Country; #19 Pop) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Lq0fUa0vW_E There is a key change between each of the five verses, and Cash hums the new root note before singing each verse. The final verse, a reprise of the first, is sung a full octave lower than the first verse. My Blue Heaven, Fats Domino, 1956 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CS75X7perbI Sold over 5 million copies in 1928 as recorded by Gene Austin. Money Honey, Elvis Presley, 1956 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=R-4KROtI1yM Compare: The Drifters (McPhatter) (1953) https://youtu.be/N8oNHMNCSjQ Roll Over Beethoven, Chuck Berry, 1956 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zD80CostTV0 The Magic Touch, The Platters, 1956 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iVX6f3OZ35o * * * * Some notes (to be discussed in class): FATS DOMINO -Born in New Orleans. -

An Investigation Into the Origin of Jamaican Ska Paul Kauppila San Jose State University, [email protected]

San Jose State University SJSU ScholarWorks Faculty and Staff ubP lications Library January 2006 From Memphis to Kingston: An Investigation into the Origin of Jamaican Ska Paul Kauppila San Jose State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/lib_pub Part of the Music Commons, and the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Paul Kauppila. "From Memphis to Kingston: An Investigation into the Origin of Jamaican Ska" Social and Economic Studies (2006): 75-91. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Library at SJSU ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty and Staff Publications by an authorized administrator of SJSU ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. "FROM MEMPHIS TO KINGSTON": AN INVESTIGATION INTO THE ORIGIN OF JAMAICAN SKA Kauppila, Paul Social and Economic Studies; Mar/Jun 2006; 55, 1/2; ABI/INFORM Complete pg. 75 Social and Economic Studies 55: I & 2 (2006): 75-91 ISSN: 0037-7651 "F"ROM MEMPHIS TO KINGSTON": AN INVESTIGATION INTO THE ORIGIN OF" .JAMAICAN SKA F'AUL KAUPPILA ABSTRACT The distinguishing characteristic of most Jamaican popular music recordings, including reggae and its predecessor, ska, is an emphasis on the offbeat or afterbeat instead of on the downbeat as found in most American popular music. Many explanations have been proposed to explain this tendency. This study critically examines these theories through historical and musicological analyses and concludes that the prevalence of the downbeat is a mixture of Jamaican folk and African-American popular music influences in its earliest incarnation, but was later deliberately emphasized in an attempt to create a unique new musical style. -

The R&B Pioneers Series

The Great R&B Files (# 11 of 12) Updated March 1, 2019 The R&B Pioneers Series Compiled by Claus Röhnisch Special Supplement: Top 30 Favorites - featuring the Super Legends’ Ultimate CD compilations, their very first albums, * and ± .. plus their most classic singles. Top Rhythm & Blues Records - The Top R&B Hits from 30 classic years of Rhythm & Blues THE Blues Giants of the 1950s THE Top Ten Vocal Groups of the Golden ‘50s Ten Sepia Super Stars of Rock ‘n’ Roll Transitions from Rhythm to Soul – Twelve Original Soul Icons The True R&B Pioneers – Twelve Hit-Makers of the Early Years Predecessors of the Soul Explosion in the 1960s Clyde McPhatter – The Original Soul Star The John Lee Hooker Session Discography The Clown Princes of Rock and Roll: The Coasters Those Hoodlum Friends – The Coasters Page 1 (94) THE R&B PIONEERS Series - Volume Eleven of twelve Compiled by Claus Röhnisch The R&B Pioneers Series: find them all at The Great R&B-files Created by Claus Röhnisch http://www.rhythm-and-blues.info (try the links her on the next page for youtube) Vol 1. Top Rhythm & Blues Records The Top R&B Hits from 30 classic years of Rhythm & Blues Vol 2. The John Lee Hooker Session Discography Complete discography, year-by-year recap, CD-Guide, and more John Lee Hooker – The World’s Greatest Blues Singer Vol 3. The Clown Princes of Rock and Roll Todd Baptista’s great Essay on The Coasters, completed with Singles Discography, Chart Hits, Session Discography, and much more Vol 4. -

Cosimo Matassa 2012.Pdf

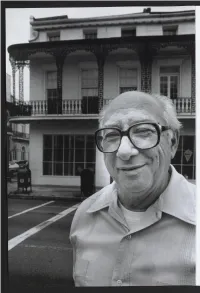

AWARD FOR MUSICAL EXCELLENCE BEN SANDMEL NO AUDIO ENGINEER HAS THRILLED MORE LISTENERS udio engineers rarely get credit for their that lasted until the early sixties. This era came to he known crucial contributions to hits. But the sound of a as the Golden Age of New Orleans rhythm & blues. A recording—just as much as a song’s rendition— Born on April 13,1926, Matassa started out in music often provides the intangible element that puts it across. by selling used records from his father’s jukebox business. Listeners rarely identify this certain something as the hook Sales were brisk, so he expanded his stock to include new that grabs them. Without its imperceptible appeal, however, releases. Then he had an epiphany. “It seemed to me,” he they simply may not respond, and a hit will not ensue. said, with considerable understatement, “that a recording No audio engineer has thrilled more listeners by im outlet for a city with so much music in it was a good idea.” buing more hits with more sonic excitement than Cosimo And thus he came to create one. Matassa. Matassa worked on a shoestring budget. H isJ&M Matassa recorded a host of New Orleans R& B icons Studio in New Orleans occupied less than three hundred during the city’s glory years, including Fats Domino, square feet. He used extremely minimal equipment. But Lloyd Price, Irma Thomas, Frankie Ford, Lee Dorsey, Matassa had a keen ear and a knack for making technically Ernie K-Doe, Aaron Neville, Huey “Piano” Smith and the primitive recordings that burst with punch, presence, and Clowns, Smiley Lewis, Shirley and Lee, and the Meters, instant danceability. -

Roots and Branches Handout SESSIONS Revnov20

THE LIVING, BREATHING ART OF MUSIC HISTORY: THE ROOTS AND BRANCHES COURTESY OF WWW.THESESSIONS.ORG COUNTRY: THE ROOTS: The Carter Family/Roy Acuff/Kitty Wells/Hank Williams/Bob Wills & His Texas Playboys BRANCHES: Men: Johnny Cash/George Jones/Waylon Jennings/Conway Twitty/Charlie Pride/The Everly Brothers (see also Rock n’ Roll) WOMEN: Patsy Cline/Loretta Lynn/June Carter/Tammy Wynette/ Dolly Parton INFLUENCED: Jack White, Zac Brown TRIBUTARY: BLUEGRASS : Bill Monroe/Ralph & Carter Stanley/Ricky Scaggs/Allison Krauss TRIBUTARY: COUNTRY ROCK: The Byrds (“Sweetheart Of The Rodeo”)/Poco/early Eagles/Graham Parsons/Emmylou Harris THE BLUES: THE ROOTS (Men): (Delta) Robert Johnson /Son House /Charlie Patton/Mississippi John Hurt/WC Handy/Lonnie Johnson (Chicago) Muddy Waters/Howlin’ Wolf/Little Walter /Buddy Guy/Otis Rush/Elmore James/Jimmy Reed - (Detroit) John Lee Hooker - (Mississippi) BB King/Albert King - (Texas) Freddie King BRANCHES: Stevie Ray Vaughn/Jimi Hendrix/Led Zepplin/ The Fabulous Thunderbirds/Cream/Eric Clapton/early Fleetwood Mac/Allman Brothers/Santana/Paul Butterfield Blues Band MODERN: Robert Cray/Joe Bonamassa/ Warren Haynes/Keb Mo TRIBUTARY- TRANCE BLUES-Oxford MS -Black Possum Records—RL Burnside, Junior Kimbrough (The Black Keys are their disciples) THE BLUES: THE ROOTS (Women): Ma Rainey/Bessie Smith/Sister Rosetta Tharpe (see also “Rock and Roll”) Memphis Minnie (influenced Led Zepplin) BRANCHES (including Jazz) : Billie Holiday/ Dinah Washington/Peggy Lee/Lena Horne/Janis Joplin/Paul Butterfield Blues Band/Michael