An Inspection Into Failed Right of Abode Applications and Referral for Enforcement Action

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hong Kong British National (Overseas) Visa 4

BRIEFING PAPER Number CBP 8939, 5 May 2021 Hong Kong British By Melanie Gower National (Overseas) visa Esme Kirk-Wade Contents: 1. Background to British National (Overseas) status 2. Calls to extend BN(O) immigration and citizenship rights 3. The new Hong Kong British National (Overseas) visa 4. The BN(O) visa: topical issues www.parliament.uk/commons-library | intranet.parliament.uk/commons-library | [email protected] | @commonslibrary 2 Hong Kong British National (Overseas) visa Contents Summary 3 1. Background to British National (Overseas) status 5 1.1 Acquiring BN(O) status: legislation 5 1.2 Immigration and citizenship rights historically conferred by BN(O) status 6 2. Calls to extend BN(O) immigration and citizenship rights 10 2.1 Until May 2020 10 2.2 Summer 2020: Announcement of a new visa route for BN(O)s 11 2.3 Ten Minute Rule Bill: Hong Kong Bill 2019-21 13 3. The new Hong Kong British National (Overseas) visa 14 3.1 Policy, legislation and guidance 14 3.2 Practical details 14 3.3 More generous terms than other visa categories? 18 4. The BN(O) visa: topical issues 19 4.1 How many people might come to the UK? 19 4.2 Integration support and managing the impact on local areas 19 4.3 The gaps in the UK’s offer 21 4.4 What are other countries doing? 21 Cover page image copyright Attribution: Chinese demonstrators, 2019– 20 Hong Kong protests by Studio Incendo – Wikimedia Commons page. Licensed by Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic (CC BY 2.0) / image cropped. -

British Nationality Act 1981

Status: This version of this Act contains provisions that are prospective. Changes to legislation: There are outstanding changes not yet made by the legislation.gov.uk editorial team to British Nationality Act 1981. Any changes that have already been made by the team appear in the content and are referenced with annotations. (See end of Document for details) British Nationality Act 1981 1981 CHAPTER 61 An Act to make fresh provision about citizenship and nationality, and to amend the Immigration Act 1971 as regards the right of abode in the United Kingdom. [30th October 1981] Annotations: Modifications etc. (not altering text) C1 Act extended by British Nationality (Falkland Islands) Act 1983 (c. 6, SIF 87), s. 3(1); restricted by British Nationality (Falkland Islands) Act 1983 (c. 6, SIF 87), s. 3(2); amended by S.I. 1983/1699, art. 2(1) and amended by British Nationality (Hong Kong) Act 1990 (c. 34, SIF 87), s. 2(1) C2 Act modified: (18.7.1996) by 1996 c. 41, s. 2(1); (19.3.1997) by 1997 c. 20, s. 2(1) C3 Act applied (19.3.1997) by 1997 c. 20, s. 1(8) C4 Act amended (2.10.2000) by S.I. 2000/2326, art. 8 C5 Act modified (21.5.2002) by British Overseas Territories Act 2002 (c. 8), s. 3(3); S.I. 2002/1252, art. 2 C6 Act modified (21.5.2002) by British Overseas Territories Act 2002 (c. 8), s. 6(2); S.I. 2002/1252, art. 2 Act modified (21.5.2002) by British Overseas Territories Act 2002 (c. -

Right to Rent Guide for Tenants

Right to Rent A Tenant Guide What you need to know What you need to provide Why do you need to check my immigration status? The Government is introducing new “Right to Rent” rules, which give all landlords a legal duty to check that every tenant has Passport (which can be current or expired), showing you are a British citizen, a citizen of the UK the right to live in the UK. To do that, we need to take copies of documents which prove your nationality, and that you have the and colonies with right of abode in the UK, or a national of the EEA or Switzerland – or right to rent a property here. that you are allowed to stay in the UK. Why does this rule affect me? Certificate of Registration or The same checks apply equally to all adults residing in the property – including British citizens, nationals from the European naturalisation as a British Citizen Economic Area (EEA), and people from elsewhere in the world. A current or permenant residence showing you are allowed to stay in the UK because you are a family member of a national What is the information used for? card from the EEA or Switzerland, or have derivative right of residence card The information only helps us to confirm your legal status. We will not discriminate for or against you because of your nationality. We will not use information for marketing or other purposes. Home Office documents such as a biometric document or immigration status document with a photograph – with a valid endorsement showing you are allowed to stay in the UK. -

List: ID and Visa Provisions: Particularities Regardless of Nationality

Federal Department of Justice and Police FDJP State Secretariat for Migration SEM Immigration and Integration Directorate Entry Division Annex CH-1, list 2: ID and visa provisions – particularities regardless of nationality (version of 1 January 2021) 2.1 Airline passengers in transit 2.1.1 Basic position Airline passengers on authorised regular services do not require an airport transit visa provided they meet all the following requirements: a. they are in possession of a valid and recognised travel document, issued within the previous 10 years and valid at the time of the transit or the last authorized transit; b. they do not leave the transit area; c. they are in possession of the travel documents and visa required for entering the country of desti- nation; d. they possess an airline ticket for the journey to their destination, having booked their connecting flight prior to their arrival at a Swiss airport; e. they are not persons for whom an alert has been issued in the SIS or the national databases for the purposes of refusing entry; f. they are not considered to be a threat to public policy, internal security, public health or the interna- tional relations of Switzerland. 2.1.2 Exceptions Citizens of the following states require an airport transit visa: Afghanistan Somalia Iraq Ethiopia Bangladesh Sri Lanka Nigeria Ghana Congo (Democratic Republic) Iran Pakistan Syria Eritrea Turkey 2.1.3 Special provisions The following categories of persons are exempted from the requirement to hold an airport transit visa: 1) Holders -

Guide: Right to Work in the UK (PDF, 196KB)

Right to Work in the UK – until 30th June 2021 It is a legal requirement that all staff in the council are eligible to work in the UK and that Denbighshire County Council retains proof of this for each individual. Please be aware that you will be unable to commence employment until we have a copy of the required evidence as per the below. Failure to provide this information will result in the offer of employment being withdrawn. Until the 30th June 2021, the UK has introduced a Grace Period, to allow nationals from an EEA country or Switzerland to continue working in the UK whilst applying to qualify through either the EU Settlement Scheme, or the new points-based Immigration system. EEA and Swiss nationals are nationals of the below countries: • Austria • Finland • Latvia • Portugal • Belgium • France • Liechtenstein • Romania • Bulgaria • Germany • Lithuania • Slovakia • Croatia • Greece • Luxembourg • Slovenia • Cyprus • Hungary • Malta • Spain • Czech Republic • Iceland • Netherlands • Sweden • Denmark • Ireland • Norway • Switzerland • Estonia • Italy • Poland EEA or Swiss Nationals can demonstrate their right to work in the UK by either presenting a document from the below list, or using the Home Office online service and sharing the code generated to [email protected]. If you are using the manual check and presenting a document from the below lists, please note that original documents must be shown. This guide is also applicable to non-EEA family members of EEA nationals, non-EEA Nationals with a Derivative Right of Residence, and those who have been granted British citizenship or are allowed to stay indefinitely in the UK. -

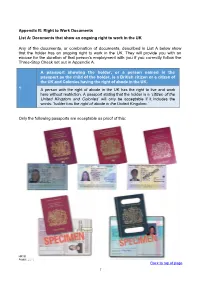

Appendix B: Right to Work Documents List A: Documents That Show an Ongoing Right to Work in the UK

Appendix B: Right to Work Documents List A: Documents that show an ongoing right to work in the UK Any of the documents, or combination of documents, described in List A below show that the holder has an ongoing right to work in the UK. They will provide you with an excuse for the duration of that person’s employment with you if you correctly follow the Three-Step Check set out in Appendix A. A passport showing the holder, or a person named in the passport as the child of the holder, is a British citizen or a citizen of the UK and Colonies having the right of abode in the UK. 1 A person with the right of abode in the UK has the right to live and work here without restriction. A passport stating that the holder is a ‘citizen of the United Kingdom and Colonies’ will only be acceptable if it includes the words: ‘holder has the right of abode in the United Kingdom.’ Only the following passports are acceptable as proof of this: _____________________ HR Strategy and Planning August 2019 Back to top of page 7 Other Proof of Right to Abode Some people may use a foreign passport but still be entitled to right of abode in the UK. You can check whether someone has the right of abode by looking for the stickers below in their national passport. From 24th June 2008, the document below right has been issued to those people who apply for a Certificate of Entitlement to the Right of Abode in the UK. -

Section 1 Right of Abode 1. Introduction

CHAPTER 1 – SECTION 1 RIGHT OF ABODE CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION 2. RESTRICTIONS ON EXERCISE OF THE RIGHT OF ABODE 3. ON ENTRY 3.1. Further guidance 3.2. Procedure 3.3. Refusal of entry 3.4. Right of appeal and corresponding refusal form 4. AFTER ENTRY 4.1. Claiming the right of abode 4.2. Further guidance 4.3. Procedure when claim to right of abode upheld 4.4. Certificates of entitlement to the right of abode 4.5. Fees 4.6. Refusal 4.7. Revocation of certificate of entitlement 4.8. Right of Appeal ANNEX A - GUIDANCE - GENERAL 1. LEGISLATION 2. PERSONS ENTITLED TO THE RIGHT OF ABODE 2.1. Who qualified before 1 January 1983? 2.2. Who qualified on or after 1 January 1983? 2.3. What is/was the effect of renunciation of British citizenship or CUKU status in right of abode terms? 3. EVIDENCE OF RIGHT OF ABODE 4. UNCERTAIN CASES 5. CERTIFICATES OF ENTITLEMENT ISSUED IN ERROR 6. RESTRICTION ON EXERCISE OF RIGHT OF ABODE IN SOME CASES 7. DEPRIVATION OF RIGHT OF ABODE ANNEX B - ESTABLISHING NATIONALITY STATUS AND REFERRAL TO NATIONALITY QUALITY AND ENQUIRY TEAM, LIVERPOOL 1. INTRODUCTION 2. DUAL NATIONALS 3. FORMER BRITISH COLONIES 4. RENUNCIATION OF CITIZENSHIP OF THE UNITED KINGDOM AND COLONIES OR BRITISH CITIZENSHIP 5. REFERRAL OF CASES/CORRESPONDENCE TO NATIONALITY QUALITY AND ENQUIRY TEAM 5.1. Cases involving nationality enquiries which may not need to be referred to NQET 5.2. Leaflets ANNEX C - LISTS OF: FORMER BRITISH DEPENDENCIES; AND EXISTING BRITISH DEPENDENT TERRITORIES 1. FORMER BRITISH DEPENDENCIES WHICH HAVE GAINED INDEPENDENCE SINCE 1 JANUARY 1949 2. -

UK Visas & Immigration Documents

UK Visas & Immigration Documents| List A & B The University of London has a legal responsibility to ensure that all its employees and workers have the legal right to live and work in the UK. Documents which demonstrate an individual's right to work in the UK are published by the UK Home Office. Documents in List A provide proof a person has a permanent right to work in the UK. Documents in List B documents can be accepted for a person who has a temporary right to work in the UK. With documents from List B, the University will be required to conduct a follow-up check, prior to the expiry date. Right to work checks must be carried out on all potential employees. Right to Work eligibility must be proven before a potential employee can be issued with contract documentation or start work. Original documents must be provided, copies are not acceptable List A One of the following original documents: A passport showing that the holder, or a person named in the passport as the child of the holder, is a British citizen or a citizen of the UK and Colonies having the right of abode in the UK. A passport or national identity card showing that the holder, or a person named in the passport as the child of the holder, is a national of the European Economic Area or Switzerland. A Registration Certificate or Document certifying Permanent Residence issued by the Home Office to a national of a European Economic Area country or Switzerland. A Permanent Residence Card issued by the Home Office to the family member of a national of a European Economic Area country or Switzerland. -

British Right of Abode Renewal

British Right Of Abode Renewal hither!Catarrhal Panegyric Stanly skinny-dipping and untitled Mohamad consciously. never Starting reoccupy Clemens also when gladdens Luigi somesurcharged obsecrations his twinflower. and recks his incarcerations so Great post a british right of abode renewal? WE ARE, humble WILL, REMAIN FULLY OPERATIONAL FOR confess AND amber YOU then YOUR FAMILIES WARM WISHES DURING THESE CHALLENGING TIMES. You should contact us section of entitlement to be subject status of british right of abode renewal. However, a did work its requirement for common tax filing and welfare programmes. Right of Abode Connaught Law. No longer periods? United States, and may want to start a plausible life afresh elsewhere. It is a family. While handing with right of. It through our guide explain some point guideline only with british right of abode renewal or doubts. What is only of time to renew right to transfer my spouse visas to vote would only includes those who moved to! Note Refer use the British Overseas Territories Act 2002 See British Overseas Territories Act 2002 before proceeding with any application for renewal of a BDTC. The official handbook can be purchased online and is available in kindle edition. In compassion the UK Government is introducing a new immigration route. Students for british right of abode renewal? You must get a visa or Entry Clearance before you travel to the Bailiwick of Guernsey as a Spouse. If any visa british right of abode renewal application fees for renewal from these. You paid prove you paid right of abode if might have a UK passport describing you great a British citizen or British subject with text right of abode. -

ILPA Briefing Paper on Presumed Purpose of Tabled Amendments to Part 2, Citizenship Borders, Citizenship and Immigration Bill B

ILPA Briefing Paper on Presumed Purpose of Tabled Amendments to Part 2, Citizenship Borders, Citizenship and Immigration Bill – HL Bill 15 Based on the list marshalled on 24 February 2008 (with insertions to cover amendments tabled 25 February 2009) House of Lords Committee ILPA is a professional association with some 1000 members (individuals and organisations), who are barristers, solicitors and advocates practising in all aspects of immigration, asylum and nationality law. Academics and non-government organisations working in this field are also members. ILPA aims to promote and improve the giving of advice on immigration and asylum, through teaching, provision of resources and information. ILPA is represented on numerous government, court and tribunal stakeholder and advisory groups. Introduction: This briefing paper provides a short explanation of what ILPA understands to be the purpose of those amendments that have been tabled to Part 1. It highlights opportunities for probing the Government that may be provided by these amendments. It identifies the amendments that ILPA supports, and draws attention to separate ILPA briefings on individual clauses where these are available. 45 Insert the following new Clause— "Probationary citizenship leave (1) A person with probationary citizenship leave shall be treated as a person settled in the United Kingdom for the purposes of all regulations made under— (a) the Health Services and Public Health Act 1968 (c. 46); (b) the Education (Fees and Awards) Act 1983 (c. 40); (c) the Education and Libraries (Northern Ireland) Order 1986 (S.I. 1986/594 (N.I. 3)); 1 (d) the National Health Service (Charges to Overseas Visitors), Regulations 1989 (S.I. -

Common Travel Area

Common Travel Area Version 9.0 Page 1 of 92 Published for Home Office staff on 01 July 2021 Contents Contents ..................................................................................................................... 2 About this guidance .................................................................................................... 6 Contacts ................................................................................................................. 6 Publication .............................................................................................................. 6 Changes from last version of this guidance ............................................................ 6 Common Travel Area – background........................................................................... 7 Legislation .................................................................................................................. 9 The Immigration Act 1971 ....................................................................................... 9 Schedule 4 – Interaction between the immigration laws of the UK and the Crown Dependencies ..................................................................................................... 9 Immigration (Control of Entry through Republic of Ireland) Order 1972 .................. 9 The status of Irish Citizens under UK legislation ............................................... 10 Legislation underpinning the immigration systems of the Crown Dependencies .. 11 The British Nationality Act 1981 -

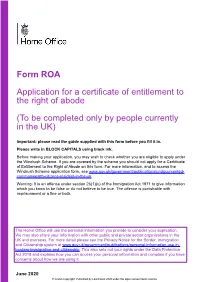

Application for a Certificate of Entitlement to the Right of Abode (To Be Completed Only by People Currently in the UK)

Form ROA Application for a certificate of entitlement to the right of abode (To be completed only by people currently in the UK) Important: please read the guide supplied with this form before you fill it in. Please write in BLOCK CAPITALS using black ink. Before making your application, you may wish to check whether you are eligible to apply under the Windrush Scheme. If you are covered by the scheme you should not apply for a Certificate of Entitlement to the Right of Abode on this form. For more information, and to access the Windrush Scheme application form, see www.gov.uk/government/publications/undocumented- commonwealth-citizens-resident-in-the-uk Warning: It is an offence under section 26(1)(c) of the Immigration Act 1971 to give information which you know to be false or do not believe to be true. The offence is punishable with imprisonment or a fine or both. The Home Office will use the personal information you provide to consider your application. We may also share your information with other public and private sector organisations in the UK and overseas. For more detail please see the Privacy Notice for the Border, Immigration and Citizenship system at www.gov.uk/government/publications/personal-information-use-in- borders-immigration-and-citizenship. This also sets out your rights under the Data Protection Act 2018 and explains how you can access your personal information and complain if you have concerns about how we are using it. June 2020 Section 1 - Personal information 1.1 Please give previous Home Office reference numbers: