EDUCATORS on the EDGE: Big Ideas for Change and Innovation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Apple Distinguished Schools March 2021

Apple Distinguished Schools Europe, Middle East, Overview Americas Asia Pacific Higher Education School Profiles India, Africa We believe Apple Distinguished Schools are some of the most innovative schools in the world. They’re centers of leadership and educational excellence that demonstrate our vision of exemplary learning environments. They use Apple products to inspire student creativity, collaboration, and critical thinking. Leadership in our recognized schools cultivate environments in which students are excited about learning, curiosity is fostered, and learning is a personal experience. Americas Asia Pacific Europe, Middle East, India, Africa Brazil > Australia > Belgium > Poland > Canada > China > Denmark > South Africa > Mexico > Hong Kong > France > Spain > United States > Indonesia > Germany > Sweden > Japan > India > Switzerland > Malaysia > Ireland > Turkey > 546 New Zealand > Italy > UAE > Schools Philippines > Netherlands > United Kingdom > Singapore > Norway > 32 South Korea > Countries Thailand > Higher Education Vietnam > View all > 2 Europe, Middle East, Overview Americas Asia Pacific Higher Education School Profiles India, Africa United States Click a school name to visit their website. Alabama Mater Dei High School, Santa Ana Lee-Scott Academy, Auburn McKinna Elementary School, Oxnard Madison Academy, Madison Merryhill Midtown Elementary and Middle School, Sacramento Piedmont Elementary School, Piedmont Oakmont Outdoor School, Claremont Piedmont High School, Piedmont Olivenhain Pioneer, Carlsbad Robert C. Fisler School, -

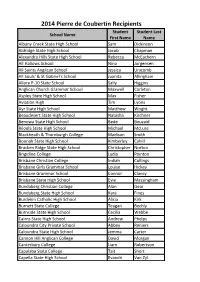

2014 Pierre De Coubertin Recipients

2014 Pierre de Coubertin Recipients Student Student Last School Name First Name Name Albany Creek State High School Sam Dickinson Aldridge State High School Jacob Chapman Alexandra Hills State High School Rebecca McEachern All Hallows School Nina Jorgensen All Saints Anglican School Jessica Unicomb All Souls' & St Gabriel's School Juanita Allingham Allora P-10 State School Sally Higgins Anglican Church Grammar School Maxwell Carleton Aspley State High School Max Fisher Aviation High Tim Lyons Ayr State High School Matthew Wright Beaudesert State High School Natasha Kirchner Benowa State High School Bede Bouzaid Biloela State High School Michael McLure Blackheath & Thornburgh College Madison Smith Boonah State High School Kimberley Cahill Bracken Ridge State High School Christopher Norton Brigidine College Lydia Pointon Brisbane Christian College Indiah Collings Brisbane Girls Grammar School Louise Hickey Brisbane Grammar School Connor Clancy Brisbane State High School Evie Massingham Bundaberg Christian College Alan Gear Bundaberg State High School Kara Fines Burdekin Catholic High School Alicia Kirk Burnett State College Teagan Bechly Burnside State High School Cecilia Webbe Cairns State High School Andrew Phelps Caloundra City Private School Abbey Reniers Caloundra State High School Jemma Carter Cannon Hill Anglican College David Morgan Canterbury College Liam Robertson Capalaba State College Tait Short Capella State High School Evandri Van Zyl 2014 Pierre de Coubertin Recipients Student Student Last School Name First Name Name Carmel -

Bachelor of Education (Honours) (BEDH) - Bed(Hons) (2021)

Consult the Handbook on the Web at http://www.usq.edu.au/handbook/current for any updates that may occur during the year. (DISCONTINUED) Bachelor of Education (Honours) (BEDH) - BEd(Hons) (2021) Bachelor of Education (Honours) (BEDH) - BEd(Hons) This program is offered only to continuing students. No new admissions will be accepted. Students who are interested in this study area should contact us On-campus Online Start: No new admissions No new admissions Campus: Toowoomba, Spring®eld - Fees: Commonwealth supported place Commonwealth supported place Domestic full fee paying place Domestic full fee paying place International full fee paying place International full fee paying place Standard duration: 4 years full-time, 9 years part-time Program From: ; Bachelor of Education articulation: Contact us Current students Ask a question Freecall (within Australia): 1800 007 252 Phone (from outside Australia): +61 7 4631 2285 Email: [email protected] Professional accreditation Graduates from the program will have met the quali®cations requirement for teacher registration with the Queensland College of Teachers. All students, domestic and international, must complete the majority of supervised professional experience in Australian Primary and/or Secondary school settings. Graduates from the BEd (Hons) (Early Childhood) will have also met the requirements of the Of®ce for Early Childhood Education and Care (formerly the Queensland Department of Communities). Program aims The Bachelor of Education (Honours) program aims to graduate students who -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. University Microfilms International A Bell & Howell Information Company 3 0 0 North Z eeb Road, Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 800/521-0600 Order Number 9211230 A study of Thai secondary school EFL teachers’ perceptions of their preparation to teach English Unyakiat, Phonthip, Ph.D. -

Barber, Indigo 06 1 Bennett, Jemima 06 2 Bond, Eleanor 06 3 Dickfos

Queensland Sport & Athletics Centre - Site License Hy-Tek's MEET MANAGER 5:11 PM 18/08/2020 Page 1 2020 All Schools Cross Country Series #2 - 22/08/2020 Minnippi Parklands Performance List - All Schools Series XC#2 Event 1 Girls 14 Year Olds 4000 Metre (29) Saturday 22/08/2020 - 1:30 PM Name Year Team Seed Time Finals Place 1 Barber, Indigo 06 Brisbane State High ________________________ 2 Bennett, Jemima 06 St Aidan's Ags ________________________ 3 Bond, Eleanor 06 Ipswich Girls Grammar ________________________ 4 Dickfos, Arabella 06 St Aidan's Ags ________________________ 5 Ellice, Bridie 06 Brigidine College ________________________ 6 Gigliotti, Gabriella 06 Springfield Anglican ________________________ 7 Gilroy, Georgie 06 Una ________________________ 8 Hannigan, Tess 06 Trinity College ________________________ 9 Hooper, Gemma 06 Sheldon College ________________________ 10 Johnson, Gretta 06 Stuartholme School ________________________ 11 Johnson, Leila 06 Clayfield College ________________________ 12 Magnisalis, Amber 06 Varsiity College ________________________ 13 McElroy, Ava 06 Moreton Bay College ________________________ 14 McGrath, Mia 06 Loreto College ________________________ 15 Michell, Chloe 06 Sheldon College ________________________ 16 Moore, Erica 06 Una ________________________ 17 Neumeister, Vienna 06 Canterbury College ________________________ 18 Norton, Amber 06 The Gap State High School ________________________ 19 Place, Roxanne 06 Moreton Bay College ________________________ 20 Rayward, Jasmine 06 Benowa Shs ________________________ -

2013 Annual Report

Bk uny VOLLEYBALL QUEENSLAND 2013 Annual Report Table of Contents Board & Executive ................................................................................................................................................. 2 President’s Report ................................................................................................................................................ 3 Finance Director’s Report ..................................................................................................................................... 5 General Manager’s Report ................................................................................................................................... 6 Events .................................................................................................................................................................... 7 Greater Public School Volleyball ........................................................................................................................................................ 7 Fraser Coast Regional Beach Volleyball Invitational .......................................................................................................................... 7 University of Oregon Exhibition Match .............................................................................................................................................. 8 2013 Annual Awards Evening ........................................................................................................................................................... -

P O Stgradu Ate Gu Id E 20 20

Contact us Postgraduate guide 2020 1800 SYD UNI (1800 793 864) Teaching and Professional Education +61 2 8627 1444 (outside Australia) sydney.edu.au/ask We acknowledge the tradition of custodianship and law of the Country on which the University of Sydney campuses stand. We pay our respects to those who have cared and continue to care for Country. Forest Stewardship Council (FSC®) is a globally recognised certification overseeing all fibre sourcing standards. This provides guarantees for the consumer that products are made of woodchips from well-managed forests and other controlled sources with strict environmental, economical and social standards. Join us Where will postgraduate study lead you? ....... 2 Teaching Master of Teaching ..............................................4 Master of Teaching (Early Childhood) ............. 5 Master of Teaching (Primary) ............................6 Master of Teaching (Health and Physical Education) ....................... 7 Master of Teaching (Secondary) ....................... 8 Postgraduate guide 2020 and Education Professional Teaching Professional education Master of Education .......................................... 10 Master of Education (Digital Technologies) ...12 Master of Education (Educational Management and Leadership) .........................13 Master of Education (Educational Psychology) ................................. 14 Master of Education (International Education) ..................................15 Master of Education (Leadership in Aboriginal Education)..............16 -

2014 International Conference Awards Feature Certified Advancement Practitioner Training Our First Ambassador

November 2014 2014 International Conference Awards Feature Certified Advancement Practitioner Training Our First Ambassador FEATURED ARTICLES The Changed Face of Crisis Communications Sam Elam The Science of Viral Content Strategy Cameron Pegg Creating a High Performance Leadership Culture Jeremy Carter How do we Solve a Problem like Generation Y? Harmonie Farrow Five Lessons in Campaign Management Brian Bowamn WE CONSULT, CREATE & PRODUCE VIDEOS FOR EDUCATION Producing compelling, fast-paced content through the eyes of entertainment with our primary focus on the youth market. (Education Packages start from $5,000) WWW.DEPARTMENTOFTHEFUTURE.COM.AU [email protected] CONTACT US: +613 9822 6451 2 EDUCATE PLUS Contents 03 The Board 2014 04 From the Chair 06-7 From the CEO 08-12 Conference 2014 14-15 Gala Event 16-17 Educate Plus Ambassador Program 18-19 Creating Leadership Culture 20-21 How do we solve the problem of Gen Y 23 Breakfast Blitz 24-29 Awards for Excellence 2014 30-33 Feature Awards 34-35 The Science of Viral Content Strategy 37-38 Five Lessons in Campaign 40-41 The Changed Face Of Crisis Communications 43 Certified Advancement Practitioner Training 45 Honouring our Fellows 46 Upcoming Chapter Conferences 47-48 Our Members Publication of Educate Plus ABN 48294772460 Enquiries: Georgina Gain, Marketing & Communications Manager, Educate Plus T +61 2 9489 0085 [email protected] www.educateplus.edu.au Cover Photo: International Conference Committee at the Conference Gala Dinner All Conference Photos by Photo Hendriks www.photohendriks.com.au Layout by Relax Design www.relaxdesign.com.au Printed by Lindsay Yates Group www.lyg.net.au All conference photos credited to Photo Hendriks FACE2FACE Nov 2014 1 Experience c unts. -

Secondary Education) (Nqf Level 8

BACHELOR OF EDUCATION HONOURS (SECONDARY EDUCATION) (NQF LEVEL 8) PURPOSE OF THE QUALIFICATION The main purpose of Bachelor of Education in secondary Education honours qualification is to produce professionally qualified teachers who are able to apply a combination of subject matter knowledge with the relevant pedagogical approaches to ensure improved learning outcomes under various contexts. The qualification will contribute to the national efforts for the production of innovative and competent Secondary school teachers who would make lasting impressions in the lives of learners. The qualification will also equip teachers with the necessary teaching skills, competencies, and strategies to be effective secondary school teachers, academic manager and administrators. Namibia’s Occupational Demand and Supply Outlook Model (NODSOM) of 2012 and other reports issued by the Ministry of Education highlight the shortage of professionally qualified teachers at all levels of the education system in Namibia. The Bachelor of Education (Secondary) Honours has been developed in response to the high demand for appropriately qualified teachers in Namibia. The rationale for the development of this qualification was motivated by the need to meet the above mentioned challenge because the targets cannot be achieved without the necessary inputs from qualified teachers who are able to implement the national curriculum and assessments. OUTCOMES FOR THE WHOLE QUALIFICATION Holders of this qualification are able to: • Teach secondary school subjects of their respective -

29/08/2020 Minnippi Parklands Results - All Schools Series XC#2

Queensland Sport & Athletics Centre - Site License Hy-Tek's MEET MANAGER Page 1 2020 All Schools Cross Country Series #2 - 29/08/2020 Minnippi Parklands Results - All Schools Series XC#2 Event 1 Girls 14 Year Olds 4000 Metre Name Yr Team Finals Finals 1 Hannigan, Tess 06 Trinity College 14:21.00 2 Johnson, Gretta 06 Stuartholme School 14:27.00 3 McElroy, Ava 06 Moreton Bay College 14:36.00 4 Norton, Amber 06 The Gap State High School 15:20.00 5 Wooldridge, Mia 06 Caloundra State High School 15:29.00 6 McGrath, Mia 06 Loreto College 15:39.00 7 Stanley, Eloise 06 Canterbury College 15:54.00 8 Barber, Indigo 06 Brisbane State High 16:17.00 9 Walsh, Millie 06 Brisbane Girls Grammar 16:25.00 10 Webb, Emily 06 Park Ridge State High School 16:29.00 11 Teale, Katelyn 06 Tamborine Mountain Shs 16:40.00 12 Rylance, Ava 06 Redlands College 17:55.00 Event 2 Boys 14 Year Olds 4000 Metre Name Yr Team Finals Finals 1 Lloyd, Oliver 06 Miami State High School 13:16.00 2 Haggerty, Angus 06 Miami State High School 13:19.00 3 Mahony, Seth 06 Brisbane Boy's College 13:30.00 4 Barr, Harrison 06 Una 13:41.00 5 Brelsford, Ethan 06 Brisbane State High 13:44.00 6 Giltrap-Good, Jake 06 Somerset College 14:06.00 7 Rayner, Lachlan 06 Brisbane Boy's College 14:11.00 8 Heath, Will 06 Brisbane State High 14:15.00 9 Smith, Christian 06 Tamborine Mountain Shs 14:16.00 10 Hogno, Timothy 06 Highlands Christian College 14:59.00 11 Tersteeg, Samuel 06 Shailer Park High 15:04.00 12 Hunt, Hudson 06 Parklands Christian College 15:06.00 13 Bannister, Jack 06 Sunhine Coast Grammar -

Download This PDF File

RECE OECD IELS statement – signatories and Canada supporters 12. Jonathan Silin, EdD Editor-In-Chief, Occasional Papers, Bank Street (see distribution by country at the bottom of the list) College of Education Fellow, Centre for Sexual Diversity Studies, 1. Sandy Farquhar, PhD University of Toronto Director Early Childhood Education Canada University of Auckland 13. Margaret J Stuart, PhD New Zealand Independent researcher 2. Claudia Diaz-Diaz, PhD Candidate New Zealand University of British Columbia 14. Vina Adriany Canada Department of Early Childhood Education 3. Elin Madil Universitas Pendidikan Otago University Childcare Association Dunedin, Indonesia New Zealand 15. Anette Hellman 4. Casey Y. Myers, PhD Department of education, communication and Assistant Professor of Early Childhood Education learning Studio & Research Arts Coordinator Child University of Gothenburg Development Center Sweden Kent State University, OH 16. Rachel Berman, PhD USA School of Early Childhood Studies 5. E Jayne White, PhD Ryerson University Associate Professor Toronto, Ontario University of Waikato Canada New Zealand 17. Janice Kroeger, PhD 6. Nikki Fairchild Associate Professor and Graduate Coordinator Senior Lecturer Early Childhood Kent State University, OH University of Chichester USA UK 18. Janette Kelly 7. Dr Zsuzsa Millei Academic Staff Member Senior Research Fellow, Institute for Advanced ECE Wintec Social Research Hamilton University of Tampere New Zealand Finland 19. Professor Jayne Osgood Senior Lecturer in Early Childhood and Centre for Education Research & Scholarship Comparative Education Middlesex University University of Newcastle London, UK Australia 20. Rebecca Hopkins 8. Joanne Lehrer Doctoral Candidate Assistant Professor The University of Auckland Université du Québec en Outaouais New Zealand Canada 21. Prof. Michel Vandenbroeck 9. -

Bachelor of Science Bed(ECE)/Bsc

Program Code: 3428 CRICOS Code: 073163K PROGRAM REGULATIONS: Bachelor of Education (Early Childhood and Care: 0-8 years)/Bachelor of Science BEd(ECE)/BSc Responsible Owner: National Head of School of Education Responsible Office: Faculty of Education and Philosophy & Theology Contact Officer: PCAC Executive Officer Effective Date: 1 January 2021 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS ............................................................................................................................ .2 2 AMENDMENTS ....................................................................................................................................... 2 3 PURPOSE ................................................................................................................................................ 3 4 OVERVIEW ............................................................................................................................................. 3 5 ENTRY REQUIREMENTS.......................................................................................................................... 3 6 PRACTICUM OR INTERNSHIP REQUIREMENTS. ..................................................................................... 4 7 PROGRAM REQUIREMENTS ................................................................................................................... 4 8 DEFINITIONS .......................................................................................................................................... 6 APPENDIX A: