01 Colonization

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

John Winthrop: America’S Forgotten Founding Father

John Winthrop: America’s Forgotten Founding Father FRANCIS J. BREMER OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS John Winthrop This page intentionally left blank John Winthrop Americas Forgotten Founding Father FRANCIS J. BREMER 2003 Oxford New York Auckland Bangkok Buenos Aires Cape Town Chennai Dar es Salaam Delhi Hong Kong Istanbul Karachi Kolkata Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Mumbai Nairobi São Paulo Shanghai Singapore Taipei Tokyo Toronto Copyright © 2003 by Oxford University Press, Inc. Published by Oxford University Press, Inc. 198 Madison Avenue, New York, New York 10016 www.oup.com Oxford is a registered trademark of Oxford University Press All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of Oxford University Press. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Bremer, Francis J. John Winthrop: America’s forgotten founding father / Francis J. Bremer. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-19-514913-0 1. Winthrop, John, 1588–1649. 2. Governors—Massachusetts—Biography. 3. Puritans—Massachusetts—Biography. 4. Massachusetts—History—Colonial period, ca. 1600–1775. 5. Puritans—Massachusetts—History—17th century. 6. Great Britain—History—Tudors, 1485–1603. 7. Great Britain—History—Early Stuarts, 1603–1649. 8. England—Church history—16th century. 9. England—Church history—17th century. I. Title F67.W79 B74 2003 974.4'02'092—dc21 2002038143 -

Notes Upon the Ancestry William Hutchinson Ne Marbury

N OTES UPON TH E ANCEST RY W I L L I A M H U T C H I N S O N NE M A R B U R Y; F R O M R E S E A R C H B S R E C E NT L Y M A D E I N E N G L A N D . B Y E - E E JO S PH L E M U L Q H E S T R , - Memb er of th e NewEngland His toric G enéalogical Society . “ B O S T O N P D C L A PP . R I N T E BY D . S O N 1 8 6 6 . THE ANCESTRY OF WILLIAM HUTCHINSON AND ANNE MARBURY. THE writ er has e i b en able , after a long and laborious investigat on , to solve th e chief doubts existing in respect to the early history and “ connections of the family of Governor Hutchinson , several of the members of which played important parts m the affairs of New Eng h e land . As has heretofore been his almost invariable experience , ffi l n has had more di culty _ clearing away the mists that have enveloped u that history , growing out of doubtful traditions and careless or wilf l a misrepresent tions , than in developing the true facts in the case when once the right clew was obtained . Before proceeding with the history of the immediate family o f the l earliest emigrant ancestor of Governor Hutchinson , it will be we l to state that there is no t the slightest authority for connecting him wi th Yo rkshire either the heraldic family of , . -

John Cotton's Middle Way

University of Mississippi eGrove Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2011 John Cotton's Middle Way Gary Albert Rowland Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/etd Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Rowland, Gary Albert, "John Cotton's Middle Way" (2011). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 251. https://egrove.olemiss.edu/etd/251 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. JOHN COTTON'S MIDDLE WAY A THESIS presented in partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of History The University of Mississippi by GARY A. ROWLAND August 2011 Copyright Gary A. Rowland 2011 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ABSTRACT Historians are divided concerning the ecclesiological thought of seventeenth-century minister John Cotton. Some argue that he supported a church structure based on suppression of lay rights in favor of the clergy, strengthening of synods above the authority of congregations, and increasingly narrow church membership requirements. By contrast, others arrive at virtually opposite conclusions. This thesis evaluates Cotton's correspondence and pamphlets through the lense of moderation to trace the evolution of Cotton's thought on these ecclesiological issues during his ministry in England and Massachusetts. Moderation is discussed in terms of compromise and the abatement of severity in the context of ecclesiastical toleration, the balance between lay and clerical power, and the extent of congregational and synodal authority. -

Joseph Atkins, the Story of a Family by Francis Higginson Atkins

9. m '!: M: E& i tr.f L>; $ ¦ii •13 Bf m m mmSßmmh m M m mif ili HStJji;! its^ii1 i j<s'.'ji !< ;1t»ii:!iJ*s il l*Jnr is Bi.i; li^i ¦?•: His !1^u:-.;i .••JRjj; R': !8! MiKftaim 'Alii n fcfJjiilS ffiii i:: !JW•M |:« 1' I, V !t?i m Ml tin =1 t , ||fgl; Ri ilSHI BS fii «a81 SSfe Mi: mmv! il »' Hi >1 Bssissi* T MM 3M71mi1; ERRATA. "P. iS, near" bottom, for" "40-S" read" "1401-08." " 49' " middle, " "women" " "woman." s°* bottom, "Addington" "Davenport." " " (See foot note to Dudley chart.) 52, middle, for "diptheria" read "diphtheria." " " bottom, " u 55. " " "Reed's" "Ree's." " 57, " "social in" U "insocial." 58, " top, " "then" "than." " 61, " bottom, " "presevere" u "persevere." " " " u "than." " 65, " top," " "then" 75. " "dosen't" u "doesn't." " 76, a middle, "frm" a "from." " " " " a " 85, " " " '"Gottingen" "Gottingen." " 98, " " "chevron" " "bend." 101, top, "unostensibly" "unostentatiously a a " bottom, " "viseed" "a "viseed." THE BARBICAN,SANDWICH, KENT, ENGLAND. JOSEPH AIKINS THE STORY OF A FAMILY •by- FRANCIS HIGGINSON ATKINS. "Itis indeed a desirable thing to be well descended, but the glory belongs to our an cestors." \ i -^ftsfftn. DUDLEYATKINS,SOOK AND JOB PRINTER. 1891. & r° t> «« "0! tell me, tell me, Tam-a-line, 0! tell, an' tell me true; Tellme this nicht, an' mak' nae lee, What pedigree are you?" —Child's Ballads. "Suppose therefore a gentleman, fullofhis illustrious family, should, in the same manner as Virgilmakes iEneas look over his descendants, see the whole line of his progenitors pass in a review before his -

Radical Republicanism in England, America, and the Imperial Atlantic, 1624-1661

RADICAL REPUBLICANISM IN ENGLAND, AMERICA, AND THE IMPERIAL ATLANTIC, 1624-1661 by John Donoghue B.A., Westminster College, New Wilmington, PA, 1993 M.A., University of Pittsburgh, 1999 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2006 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH Faculty of Arts and Sciences This dissertation was presented by John Donoghue It was defended on December 2, 2005 and approved by William Fusfield, Associate Professor, Department of Communication Janelle Greenberg, Professor, Department of History Jonathan Scott, Professor, Department of History Dissertation Director: Marcus Rediker, Professor, Department of History ii Copyright by John Donoghue 2006 iii RADICAL REPUBLICANISM IN ENGLAND, AMERICA, AND THE IMPERIAL ATLANTIC, 1624-1661 John Donoghue, Ph.D. University of Pittsburgh, April 30, 2006 This dissertation links the radical politics of the English Revolution to the history of puritan New England. It argues that antinomians, by rejecting traditional concepts of social authority, created divisive political factions within the godly party while it waged war against King Charles I. At the same time in New England, antinomians organized a political movement that called for a democratic commonwealth to limit the power of ministers and magistrates in religious and civil affairs. When this program collapsed in Massachusetts, hundreds of colonists returned to an Old England engulfed by civil war. Joining English antinomians, they became lay preachers in London, New Model Army soldiers, and influential supporters of the republican Levellers. This dissertation also connects the study of republican political thought to the labor history of the first British Empire. -

Dissenting Puritans: Anne Hutchinson and Mary Dyer.”

The Historical Journal of Massachusetts “Dissenting Puritans: Anne Hutchinson and Mary Dyer.” Author: Francis J. Bremer Source: Historical Journal of Massachusetts, Volume 46, No. 1, Winter 2018, pp. 22-45. Published by: Institute for Massachusetts Studies and Westfield State University You may use content in this archive for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the Historical Journal of Massachusetts regarding any further use of this work: [email protected] Funding for digitization of issues was provided through a generous grant from MassHumanities. Some digitized versions of the articles have been reformatted from their original, published appearance. When citing, please give the original print source (volume/number/date) but add "retrieved from HJM's online archive at http://www.westfield.ma.edu/historical-journal/. 22 Historical Journal of Massachusetts • Winter 2018 First Founders: American Puritans and Puritanism in the Atlantic World was published by the University of New Hampshire Press (2012). 23 EDITOR’S CHOICE Dissenting Puritans: Anne Hutchinson and Mary Dyer FRANCIS J. BREMER Editor’s Introduction: HJM is proud to select as our Editor’s Choice Award for this issue Francis J. Bremer’s superb biographical collection, First Founders: American Puritans and Puritanism in the Atlantic World (2012) published by the University of New Hampshire Press. Bremer, a leading authority on Puritanism and author of over a dozen books on the subject, takes a biographical approach to detail how Puritans’ ideas and values ultimately contributed to the forming of our American government and institutions. In this collection he offers mini-biographies of eighteen Puritans, including well-known figure John Winthrop. -

American Jezebel: the Uncommon Life of Anne Hutchinson, the Woman Who Defied the Puritans

Journal of International Women's Studies Volume 8 | Issue 1 Article 28 Nov-2006 Book Review: American Jezebel: The ncommonU Life of Anne Hutchinson, the Woman Who Defied the Puritans Marla Kohlman Follow this and additional works at: http://vc.bridgew.edu/jiws Part of the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Kohlman, Marla (2006). Book Review: American Jezebel: The ncU ommon Life of Anne Hutchinson, the Woman Who Defied the Puritans. Journal of International Women's Studies, 8(1), 311-313. Available at: http://vc.bridgew.edu/jiws/vol8/iss1/28 This item is available as part of Virtual Commons, the open-access institutional repository of Bridgewater State University, Bridgewater, Massachusetts. This journal and its contents may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. ©2006 Journal of International Women’s Studies. American Jezebel: The Uncommon Life of Anne Hutchinson, the Woman Who Defied the Puritans. Eve LaPlante. 2004. New York: HarperSanFrancisco. 312 pp. (Includes chronology genealogy, bibliography, and index). $24.95 (Hardcover). $14.95 (Paperback). Reviewed by Marla Kohlman1 Eve LaPlante offers a very detailed journey back to the 17th century and places the reader in the midst of the life experiences of Anne Hutchinson, John Cotton, who would become the grandfather of the infamous Puritan minister Cotton Mather, and John Winthrop, the first governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony in the United States. The text is invaluable as an explanation of how the Puritans, who were growing increasingly displeased with the Anglican Church in England, came to see themselves as a separate sect of Anglican worshippers who sought to cleave more faithfully to certain Calvinist principles from which they believed the Church of England had been led astray. -

Anne Hutchinson and the Puritans Who First Settled the New England Colony Is Not As Simplistic As We Have Been Led to Believe

The Puritans Revisited and the Arrival of Anne Hutchinson in America By Richard Forliano, Eastchester Town Historian and George Pietarinen, Author of “Anne Hutchinson, A Puritan Woman of Courage” in the book Out of the Wilderness: The Emergence of Eastchester, Tuckahoe, and Bronxville This is the second in a series of articles on the Colonial and Revolutionary History of Eastchester Anne Hutchinson is perceived as a as a feminist hero who made courageous sacrifices for the right to follow her own conscience. On the other hand, the Puritan ministers of the Massachusetts Bay Colony who persecuted Anne are viewed as members of an absolutist theocracy, intolerant bigots whose version of Christianity maintained an insular purity. The brilliance and courage of Anne Hutchinson cannot be denied. Likewise, it is wrong to cast the Puritans as simply unbending, joyless fanatics who imposed their will through strict laws and terrible punishment. Anne Hutchison would be the first European to settle in the town of Eastchester but twenty one years after her massacre by indigenous tribes, it would be Puritan farm families that first settled and cast their imprint on our town. It is imperative not to judge 17th century individuals and events in terms of our own perceptions and values. The truth about Anne Hutchinson and the Puritans who first settled the New England colony is not as simplistic as we have been led to believe. For the Puritans the desire to escape religious persecution in Europe did not led to a belief in toleration for others. For those who came to America for religious reasons, their faith was central to their entire belief system and world view. -

Morris Shirts B: 11 Aug 1899 Esclnt, UT, USA Sarah Ann Gates D: 26 Mar 1985 Orem, UT, USA B: 27 Sep 1861 USA D: 16 Sep 1944 Rchfld, UT, USA

B: 1635 Germany Hans L. Shurtz B: 14 Jun 1660 Hessen, GER Michael Schurtz Johannes Schertz D: 1 Jun 1711 W Camp, NY, USA B: 1640 NJ, USA B: 4 Dec 1679 GER Agnes Shurtz G. Schertz B: 1664 Hessen, GER E. Mueller B: 26 Mar 1721 D: 26 Nov 1759 NJ, USA D: 25 Mar 1721 New York, NY B: 1 Jan 1608 Germany NJ, USA Hans M. Stier B: 1633 Germany Michael Stier D: 9 Apr 1758 B: 1650 GER B: 1 Jan 1610 Germany Maria E. Stier Jost Georg Stier Margaretha D: 1720 British Colon... B: D: 4 Dec 1668 USA B: 23 Nov 1686 British C... Margaretha Eglin B: 1650 GER D: 19 Sep 1759 British C... Anna M. Slaeygel D: 1727 W Camp, NY, USA B: 1613 Sweden Matts Bengtson B: 1640 Stockholm, SWE C. Matthyszen D: 1685 Hcknsck, NJ, USA B: Jan Borgond ? B: B: 1 Jan 1701 Bergen, USA B: 16 Jan 1665 USA Terwilliger J. Borgand M. Mattyssen B: 1610 Vianen, NLD D: 1742 NJ, USA D. Terwilliger D: 11 Jun 1747 Bergen, NJ D: 1680 Utrecht, NLD B: B: 23 Mar 1729 ? B: 1640 Meppel, NLD NJ, USA Barentje Dirks D: 23 Dec 1681 B: 1578 Of Leiden, NLD A. Cortenbosch D: 1788 R. Mattyssen B: 1604 Leiden, NLD D: 1667 Netherlands A. Cortenbosch D: 6 Apr 1663 Leiden, NLD Michael Shurts B: 1 Jan 1750 NJ, USA D: 1830 LBN,OH, USA NJ, USA B: 1576 Netherlands B: 4 May 1705 NJ ? B: 1 Jan 1618 Leiden, NLD B: Thomas Helling Frans Hellings B: 1643 S Holland, NLD D: 1712 Zeeland, NLD Hendrick Helling D: 1718 NJ, USA B: 1 Jan 1621 Leiden, NLD W. -

The American Genealogist

Consolidated Contents of The American Genealogist Volumes 9-87; July, 1932 - July/October, 2015 Compiled by, and Copyright © 2010-2021 by Dale H. Cook This file is for personal non-commercial use only. If you are not reading this material directly from plymouthcolony.net, the site you are looking at is guilty of copyright infringement. Please contact [email protected] so that legal action can be undertaken. Any commercial site using or displaying any of my files or web pages without my express written permission will be charged a royalty rate of $1000.00 US per day for each file or web page used or displayed. [email protected] Revised March 13, 2021 A few words about the format of this file are in order. The first eight volumes of Jacobus' quarterly are not included. They were originally published under the title The New Haven Genealogical Magazine, and were consolidated and reprinted in eight volumes as as Families of Ancient New Haven (Rome, NY: Clarence D. Smith, Printer, 1923-1931; reprinted in three volumes with 1939 index Baltimore: Genealogical Publishing Co., 1974). Their focus was upon the early families of that area, which are listed in alphabetical order. With a few exceptions this file begins with the ninth volume, when the magazine's title was changed to The American Genealogist and New Haven Genealogical Magazine and its scope was expanded. The title was shortened to The American Genealogist in 1937. The entries are listed by TAG volume. Each volume is preceded by the volume number and year(s) in boldface. -

Lady Elizabeth De Burghersh, Baroness

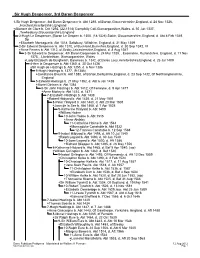

Lady Elizabeth de Burghersh, Baroness 1-Lady Elizabeth de Burghersh, Baroness b. 1342, of,Ewias Lacy,Herefordshire,England, d. 26 Jul 1409 +Sir Edward le Despencer, 4th Baron Despenser b. 24 Mar 1335, , Essendine, Rutlandshire, England, d. 11 Nov 1375, , Llanblethian, Glamorganshire, Wales 2-Ann le Despenser b. Abt 1360, d. 30 Oct 1426 +Sir Hugh de Hastings b. Abt 1355, d. 6 Nov 1386 3-Hugh Hastings b. 1377, (9:1386) +Constance Blount b. Abt 1380, of Barton,Derbyshire,England, d. 23 Sep 1432, Of Northamptonshire, England 3-Edward Hastings b. 21 May 1382, d. Abt 6 Jan 1438 +Muriel Dinham b. Abt 1384 4-Sir John Hastings b. Abt 1412, Of Fenwyke, d. 9 Apr 1477 +Anne Morley b. Abt 1414, d. 1471 5-Elizabeth Hastings b. Abt 1438 +Robert Hildyard b. Abt 1435, d. 21 May 1501 6-Peter Hildyard b. Abt 1460, d. Abt 20 Mar 1501 +Joan de la See b. Abt 1465, d. 7 Apr 1528 7-Katherine Hildyard b. Abt 1490 +William Holme 8-John Holme b. Abt 1515 +Anne Aislaby 9-Catherine Holme b. Abt 1544 +Marmaduke Constable b. Abt 1532 10-Frances Constable b. 12 Sep 1568 +John Rodes 11-Francis Rodes b. Abt 1595 +Elizabeth Lascelles 12-John Rodes b. Abt 1628 7-Isabel Hildyard b. Abt 1498, d. Aft 10 Jul 1540 +Ralph Legard b. Abt 1490, d. 30 Jun 1540 8-Joan Legard b. Abt 1530, d. Aft 1586 +Richard Skepper b. Abt 1495, d. 26 May 1556 6-Katherine Hildyard b. Abt 1465, d. Bef 5 Apr 1540, (wp) +William Girlington b. -

Sir Hugh Despencer, 3Rd Baron Despencer

Sir Hugh Despencer, 3rd Baron Despencer 1-Sir Hugh Despencer, 3rd Baron Despencer b. Abt 1288, of,Barton,Gloucestershire,England, d. 24 Nov 1326, ,Hereford,Herefordshire,England +Alianore de Clare b. Oct 1292, (22:1314) Caerphilly Cstl,Glamorganshire,Wales, d. 30 Jun 1337, ,Tewkesbury,Gloucestershire,England 2-Hugh Le Despencer, [Baron Le Despen b. 1308, (18:1326) Stoke, Gloucestershire, England, d. Abt 8 Feb 1349, Sp +Elizabeth Montague b. Abt 1318, Salisbury, Wiltshire, England, d. 31 May 1359 2-Sir Edward Despencer b. Abt 1310, of Buckland,Buckshire,England, d. 30 Sep 1342, Vf +Anne Ferrers b. Abt 1312, of,Groby,Leicestershire,England, d. 8 Aug 1367 3-Sir Edward le Despencer, 4th Baron Despenser b. 24 Mar 1335, , Essendine, Rutlandshire, England, d. 11 Nov 1375, , Llanblethian, Glamorganshire, Wales +Lady Elizabeth de Burghersh, Baroness b. 1342, of,Ewias Lacy,Herefordshire,England, d. 26 Jul 1409 4-Ann le Despenser b. Abt 1360, d. 30 Oct 1426 +Sir Hugh de Hastings b. Abt 1355, d. 6 Nov 1386 5-Hugh Hastings b. 1377, (9:1386) +Constance Blount b. Abt 1380, of Barton,Derbyshire,England, d. 23 Sep 1432, Of Northamptonshire, England 5-Edward Hastings b. 21 May 1382, d. Abt 6 Jan 1438 +Muriel Dinham b. Abt 1384 6-Sir John Hastings b. Abt 1412, Of Fenwyke, d. 9 Apr 1477 +Anne Morley b. Abt 1414, d. 1471 7-Elizabeth Hastings b. Abt 1438 +Robert Hildyard b. Abt 1435, d. 21 May 1501 8-Peter Hildyard b. Abt 1460, d. Abt 20 Mar 1501 +Joan de la See b. Abt 1465, d.