Melms V. Pabst Brewing Co

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Interpretation of the Captain Frederick Pabst Mansion: the Response Based Approach

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Theses (Historic Preservation) Graduate Program in Historic Preservation 2000 An Interpretation of the Captain Frederick Pabst Mansion: The Response Based Approach Cheryl Elaine Brookshear University of Pennsylvania Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses Part of the Historic Preservation and Conservation Commons Brookshear, Cheryl Elaine, "An Interpretation of the Captain Frederick Pabst Mansion: The Response Based Approach" (2000). Theses (Historic Preservation). 364. https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses/364 Copyright note: Penn School of Design permits distribution and display of this student work by University of Pennsylvania Libraries. Suggested Citation: Brookshear, Cheryl Elaine (2000). An Interpretation of the Captain Frederick Pabst Mansion: The Response Based Approach. (Masters Thesis). University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA. This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses/364 For more information, please contact [email protected]. An Interpretation of the Captain Frederick Pabst Mansion: The Response Based Approach Disciplines Historic Preservation and Conservation Comments Copyright note: Penn School of Design permits distribution and display of this student work by University of Pennsylvania Libraries. Suggested Citation: Brookshear, Cheryl Elaine (2000). An Interpretation of the Captain Frederick Pabst Mansion: The Response Based Approach. (Masters Thesis). University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA. This thesis or dissertation is available at ScholarlyCommons: https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses/364 ^mm^'^^'^ M ilj- hmi mmtmm mini mm\ m m mm UNIVERSITVy PENNSYLV\NL\ LIBRARIES AN INTERPRETATION OF THE CAPTAIN FREDERICK PABST MANSION: THE RESPONSE BASED APPROACH Cheryl Elaine Brookshear A THESIS in Historic Preservation Presented to the Facuhies of the University of Pennsylvania in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE 2000 V^u^^ Reader MossyPh. -

Rediscovering Milwaukee's Historic Breweries Part I: Milwaukee's Downtown Breweries Kevin M Cullen

Rediscovering Milwaukee's historic breweries Part I: Milwaukee's downtown breweries Kevin M Cullen When you mention Milwaukee, one asso- congregate in solidarity as we investigate ciation in particular comes to mind, beer. ancient and traditional alcoholic bever- This is because Milwaukee, Wisconsin ages around the world. Hence, it was a once boasted the largest production of logical and easy leap to get this eager beer than any other city in America and public on board to rediscover their own indeed the world. As an agricultural and city's brewing legacy. industrial hub on Lake Michigan for more than a century and a half with a thirsty Therefore, the first of what will be four population of ethnically proud beer ‘Legacies of Milwaukee Brewing’ tours lovers, Milwaukee was well poised to took place on 17 April 2010. It was decid- conquer the American brewing industry. ed given the breadth and scope of this What many people do not know however, city's brewing heritage, that we would is that this city has seen more than 100 focus our first tour on the historic and brewing companies come and go over contemporary breweries of downtown the past 170 years and unfortunately the Milwaukee. With Kalvin at the helm of a original breweries as well. full motor coach bus, Leonard Jurgensen as the Milwaukee brewery historian and I Therefore, as part of the Distant Mirror as the archaeological tour guide, we Archaeology Program at Discovery World made our way to one of Milwaukee's first (a science and technology museum in brewery sites at the end of Clybourn Milwaukee, Wisconsin) I am attempting Street (formerly Huron Street) and Lincoln to rediscover this brewing legacy through Memorial Drive (formerly the Lake urban archaeological expeditions. -

Greatamericanbeerfestival.Com

2012 Brewery and Brewer of the Year Awards: Small Brewpub and Small Brewpub Brewer of the Year Sponsored by Briess Malt & Ingredients Co. Devils Backbone Brewing Company - Basecamp, Roseland, VA Devils Backbone Brewery Team Large Brewpub and Large Brewpub Brewer of the Year WINNERS LIST Sponsored by Brewers Supply Group The Church Brew Works, Pittsburgh, PA Steve Sloan oct 11-13, 2012 Brewpub Group and Brewpub Group Brewer of the Year Sponsored by Brewers Supply Group Great Dane Pub & Brewing Company, Madison, WI Category: 1 American-Style Wheat Beer, 29 Entries Rob LoBreglio Gold: Wagon Box Wheat, Black Tooth Brewing Co., Sheridan, WY Silver: Shredders Wheat, Barley Brown’s Brew Pub, Baker City, OR Small Brewing Company and Small Brewing Company Brewer of the Year Bronze: American Wheat, Gella’s Diner and Lb. Brewing Co., Hays, KS Sponsored by Microstar Keg Management Category: 2 American-Style Wheat Beer with Yeast, 29 Entries Funkwerks, Fort Collins, CO Gold: MBC Wheat Ale, Montana Brewing Co., Billings, MT Funkwerks Brewing Team Silver: Tumblewheat, Altitude Chophouse and Brewery, Laramie, WY Bronze: Wrangler Wheat, Figueroa Mountain Brewing Co., Buellton, CA Mid-Size Brewing Company and Mid-Size Brewing Company Brewer of the Year Category: 3 Fruit Beer, 58 Entries Sponsored by Brewers Supply Group Gold: Dry Dock Apricot Blonde, Dry Dock Brewing Co., Aurora, CO Troegs Brewing Company, Hershey, PA Silver: ChChChCh-Cherry Bomb, Thai Me Up Brewery, Jackson, WY John Trogner Bronze: Strawberry Blonde Ale, DESTIHL, Normal, IL Large Brewing -

Final Judgment G

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF DELAWARE ) UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, ) ) Plaintiff, ) ) Civil Action No. v. ) ) FINAL JUDGMENT G. HEILEMAN BREWING COMPANY, INC. ) and PABST BREWING COMPANY, ) Filed: November 22., 1982 ) Entered: 16, 1983 Defendants. ) May WHEREAS, plaintiff, United States of America, has . filed its Complaint herein on November 22, 1982, and defendants, G. Heileman Brewing Company, Inc.("Heileman") and Pabst Brewing Company ("Pabst"), have appeared, and plaintiff and defendants, by their respective attorneya, have consented to the entry of this Final Judgment without trial or adjudication of any issue of fact or law herein, and without this Final Judgment constituting evidence, or an admission by any party, with respect to any issue of fact or law herein; WHEREAS, the following facts and circumstances underlie -the parties' agreement to the entry of this Final Judgment: Pursuant to the Agreement in Principle, as hereinafter identified and described, Heileman on November 10, 1982 commenced a tender offer for Pabst (the "tender offer") through HBC Acquisition Corporation ("HBC"), a wholly-owned aubaidiary of Heileman. The tender offer is intended as the initial step of a series of transactions whereby certain assets (the "Retained Assets" as hereinafter identified and described) owned as of November 19, 1912 by Pabst and Olympia Brewing Company ("Olympia") are to be transferred to Heileman and the balance of Pabst's and Olympia's ... assets (the •Non-Retained Assets" as hereinafter identified and described) are to be transferr ed to a new entity in which Heileman wi l l have no interest. Under the Agreement 'in Principle, upon consummation of the t e nder off er, Heileman will attempt to effect two mergers whereby HBC will acquire all of the remaining stock of Pabst and Olympia in exchange for HBC securities (the "subsequent mergers"). -

Draft Bottled Beer Old School Cans Crafty Cans

draft MILLER LITE 4 BELL’S OBERON ALE 7 ANTI-HERO IPA 6 Miller Brewing Company Bell’s Brewery (Galesburg, MI) Revolution Brewing Company (Milwaukee, WI) Wheat Ale, 5.8% ABV (Chicago, IL) Pale Lager, 4.2% ABV ALLAGASH WHITE 6 India Pale Ale, 6.5% ABV COORS LITE 4 Allagash Brewing Company (Portland, ME) DAISY CUTTER 6 Coors Brewing Company (Golden, CO) Witbier, 5% ABV Half Acre Brewing Co. (Chicago, IL) Pale Lager, 4.2% ABV FAT TIRE 6 American Pale Ale, 5.2% ABV MODELO ESPECIAL 5 New Belgium Brewing Company TBE CHARLATAN 7 Grupo Modelo (Mexico) (Fort Collins, Co) Maplewood Brewery & Distillery Pale Lager, 4.5% ABV Amber Ale, 5.2% ABV BLUE MOON 6 GUINNESS 6 (Chicago, IL) Coors Brewing Company (Golden, CO) St. James Gate (Dublin, Ireland) American Pale Ale, 6.1% ABV Belgium White Ale, 5.4% ABV Dry Stout, 4.2% ABV (Gold Medal Winner) LEINENKUGELS SUMMER SHANDY 6 STELLA ARTOIS 6 LAGUNITAS BREWERY (ROTATING) 7 Leinenkugel Brewing Company InBev Belgium (Leuven, Belgium) Lagunitas Brewing Company (Chippewa Falls, WI) Pale Lager, 5.2% ABV (Petaluma, CA & Chicago, IL) Radler/Shandy, 4.2% ABV KROMBACHER PILS 6 REVOLUTION BREWERY (ROTATING) 7 OLD STYLE COOLER BY THE LAKE 5 Krombacher Privatbrauerei Kreuztal Revolution Brewing Company Pabst Brewing Company (Krombacher, Germany) (Los Angeles, CA) (Chicago, IL) Pilsener, 4.8% ABV Radler/Shandy, 4.2% ABV THREE FLOYDS BREWERY (ROTATING) 7 ANGRY ORCHARD CRISP APPLE 5 FRESHLY SQUEEZED IPA 6 Three Floyds Brewing Company Boston Beer Company (Walden, NY) Deschutes Brewery (Bend, OR) (Munster, Indiana) Cider, -

Complaint, United States V. Pabst Brewing Co

UNIT~D STATES DISTRICT COURT EASTERN DISTRICT OF 1'1ISCONSIN UNITED STATES OF AMF.RICA, ) ) Plainti:.'f, ) ) v. ) CIVIL ACTION NO. 59-C 215 ) PABST BRE\HNG COMPANY, ) Filed: Octo~er 1, 1959 SCHENLEY INDUSTRIES, INC., ) THE VAL CORPORATION, ) ) Defendants. ) The United States of America, Plaintiff, by its attorneys, acting under the direction of the Attorney General of the United States, brings this Civil Action to obtain equitable relief against the above- named defendants, And complains and alleges as follows: ~URISDICTION AND VENUI~ 1. This complaint is filed and this action is instituted against the defendants under Section 15 of the Act of Congress of October 15, 1914, c. 323, 38 Stat. 736, ns nmended, entitled "An Act to supplement existing laws ngainst unlawful restraints and monopolies and for other purposes," commonly known as the Clayton Act, in order to prevent nnd restrain the violation by the defendants, as hereinafter alleged, of section 7 of said Act. 2. The defendant Pabst Brewing Company transacts business and is found within the Eastern District of Wisconsin. DEFENDANTS 3. Pabst Brewing Company (hllreinafter referred to as Pabst), is named a defendant herein. Pabst is a corporation organized and existing under the laws of the State of Delaware, with its principal office in Chicago, Illinois. 4, Schenley Industries, Inc. (hereinafter referred to as Schenley), is named a defendant herein. Schenley is a corporation organized and existing under the laws of the State of Delaware, with its principal office in New York City, New York. 5. Val Corporation (hereinafter referred to as Val) is named a defendant herein. -

List of OTC Market Makers, Circular No. 69-246

F e d e r a l r e s e r v e B a n k o f D a l l a s DALLAS. TEXAS 75222 Circular No. 69-2^6 September 25, 19 LIST OF OTC MARKET MAKERS To All Banks and Others Concerned in the Eleventh Federal Reserve District: Enclosed is a copy of the list of OTC market makers pub lished as of September l6, 1969* The list comprises firms that have filed Form X-17A-12(l) with the Securities and Exchange Com mission. in order to qualify as OTC market makers under section 221.3(w) of Regulation U, and the OTC margin stocks in respect of which each has qualified. The present list includes the initial list published as of July 18, 1969, and the two supplements issued as of August 8 and August 22, 19&9, as well as additional notifications filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission by broker-dealers following issuance of the August 22 supplement and ending September 16 . Additional copies of the present list will he furnished upon request. Yours very truly, P. E. Coldwell President Enclosure (l) This publication was digitized and made available by the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas' Historical Library ([email protected]) LIST OF OTC MARKET MAKERS as of September 16, 1969 (Prepared for use by banks in connection with extensions of credit pursuant to section 221.3 (w) of Regulation U) This list of "OTC market makers" comprises firms that have filed Form X-17A-12(1), the "Notification by OTC market makers in OTC margin securities," with the Securities and Exchange Commission, and the OTC margin stocks in respect of which each such firm had filed such form as of the above date. -

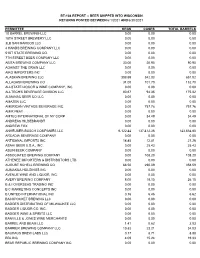

BT-100 Wisconsin Beer Production Report

WISCONSIN BEER PRODUCTION REPORT RETURNS POSTED BETWEEN 11/1/2015 AND 11/30/2015 Wisconsin Sales Out of State Sales Brewery Total Barrels Kegs Cases Kegs Cases 4 BROTHERS BLENDED BEER CO LLC 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 ALE ASYLUM, LLC 2,228.00 780.00 1,448.00 0.00 0.00 ANGRY MINNOW LLC 77.16 61.27 15.89 0.00 0.00 ARAN D MADDEN 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 ASSOCIATED BREWING COMPANY 4,184.85 0.00 13.74 8.00 4,163.11 BADERBRAU LLC 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 BADGER STATE BREWING COMPANY 67.99 41.57 26.42 0.00 0.00 LLC BARE BONES BREWERY LLC 42.25 42.25 0.00 0.00 0.00 BARLEY JOHN'S BREWING CO INC 35.60 26.44 0.00 9.16 0.00 BENT KETTLE BREWING LLC 3.50 3.50 0.00 0.00 0.00 BERGHOFF BREWERY, INC. 337.06 -5.50 59.65 107.00 175.91 BIG HEAD BREWING CO LLC 15.00 15.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 BOSTON BEER CORPORATION 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 BRENNER BREWING CO LLC 65.55 34.92 30.63 0.00 0.00 BREWERY CREEK BREWING 18.00 18.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 COMPANY BUGSY BREWING INC 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 BULL FALLS BREWERY, LLC 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 C CHRISTON LLC 18.00 18.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 CAMO BREWING CO INC 3,058.20 0.00 29.90 0.00 3,028.30 CAPITAL BREWERY COMPANY, INC. -

The Economic Impact of the Craft Beer Industry in Iowa

The Economic Impact of the Craft Beer Industry in Iowa Prepared for and funded by The Iowa Wine and Beer Promotion Board By Mike Lipsman, Harvey Siegelman, and Dan Otto Strategic Economics Group May 2015 Acknowledgements This study would not have been possible without the assistance and cooperation of a number of individuals and organizations. Colleen Murphy (Iowa Tourism Office) and J. Wilson (Iowa Brewers Guild) provided great assistance in identifying existing craft breweries and brewpubs and additional businesses still in the planning stage of development. In addition, we wish to thank them along with Ryan Rost (515 Brewing) and Bill Heinrich (Big Grove Brewery) for acting as test subjects for the Brewers Survey. We are very grateful to all of those associated with Iowa breweries and brewpubs that took time from their busy schedules to respond to the survey. Bob Bailey and Leisa Bertram (Communications Director and Accountant II, respectively, Iowa Alcoholic Beverages Division) provided invaluable help in obtaining craft beer production, distribution, and sales data, as well as information on the regulation of the industry. Also, James Morris (Iowa Workforce Development) helped by compiling and aggregating employment and wage data from Iowa breweries and brewpubs. Finally, we greatly enjoyed the visits we made to Iowa breweries and thank Dave Ropte and Ryan Rost (515 Brewing), John Martin (Confluence), and Megan McKay (Peace Tree) for the time they spent answering our many questions regarding their individual businesses and the craft beer industry. Pictures used in the report were either taken by the authors or obtained from public Internet sites. -

Download Complaint

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF DELAWARE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA ) Antitrust Division ) Department of Justice ) Washington, D.C. 20530 ) 202/633-2417, ) ) Plaintiff, ) ) CIVIL ACTION NO. 82-750 v. ) ) FILED: November 22, 1982 G. HEILEMAN BREWING COMPANY, INC. ) 100 Harborview Plaza ) Lacrosse, Wisconsin 54601, and ) ) PABST BREWING COMPANY ) 1000 North Market Street ) Milwaukee, Wisconsin 53201, ) ) Defendants. ) COMPLAINT FOR INJUNCTIVE RELIEF (ANTITRUST) I DEFINITIONS 1. "Beer" means any fermented malt beverage containing one-half of one percent or more of alcohol by volume, brewed or produced from malt, wholly or in part, or from any substitute for malt. Beer includes lager beer, dark beer, bock beer, malt liquor and ale. 2. "HHI" means the Herfindahl-Hirschman Index, a measure of market concentration calculated by squaring the market share of each firm compet ing in the market and then summing the resulting numbers. For example, for a market consisting of four firms with s hares of 30, 30, 20, and 20 per cent, the HHI is 2600 (302 + 302 + 202 + 202 = 2600). The HHI takes into account the relative size and distribution of the firms in a market. It approaches zero when a market is occupied by a large number of firms of relatively equal size and reaches its maximum of 10,000 when a market is . - . controlled by a single firm. The HHI increases both as the number of firms in the market decreases and as the disparity in size between those firms increases. II JURISDICTION AND VENUE 3. This complaint is filed and this action is instituted against the defendants under Section 15 of the Act of Congress of October 15, 1914 (15 u.s.c. -

Great Beerfestivalsm

Brewers Association Presents american SM 2007 Brewery and Brewer of the Year Awards: Large Brewing Company and Large Brewing Company Brewer of the Year GreatBEERfestival Pabst Brewing Company, Woodridge, IL i Bob Newman Mid-Size Brewing Company and Mid-Size Brewing Company Brewer of the Year OCtober 11-13, 2007 / Colorado Convention Center / Denver, CO Sponsored by Crosby & Baker Ltd. i Firestone Walker Brewing Company, Paso Robles, CA Matthew Brynildson Winners List Small Brewing Company and Small Brewing Company Brewer of the Year i Sponsored by Microstar Keg Management Port Brewing & The Lost Abbey, San Marcos, CA Tomme Arthur Category:1 American-Style Cream Ale or Lager - 24 Entries Large Brewpub and Large Brewpub Brewer of the Year Gold: Lone Star, Pabst Brewing Co., Woodridge, IL Sponsored by Brewers Supply Group Silver: Old Style, Pabst Brewing Co., Woodridge, IL RedRock Brewing Company, Salt Lake City, UT Bronze: TAPS Cream Ale, TAPS Fish House & Brewery, Brea, CA Kevin Templin Category: 2 American-Style Wheat Beer - 19 Entries Small Brewpub and Small Brewpub Brewer of the Year Gold: Pyramid Crystal Weizen, Pyramid Breweries, Seattle, OR Sponsored by Briess Malt & Ingredients Co. Silver: Brewmaster Reserve, Widmer Brothers Brewing Co., Portland, OR Montana Brewing Company, Billings, MT Bronze: Honey Weiss, Diamond Bear Brewing Co., Little Rock, AR Travis Zeilstra Category: 3 American-Style Hefeweizen - 46 Entries Gold: Whitetail Wheat, Montana Brewing Co., Billings, MT Silver: Easy Street Wheat, Odell Brewing Co., Fort Collins, -

Bt-104 Report -- Beer Shipped Into Wisconsin Returns Posted Between 6/1/2021 and 6/30/2021

BT-104 REPORT -- BEER SHIPPED INTO WISCONSIN RETURNS POSTED BETWEEN 6/1/2021 AND 6/30/2021 PERMITTEE KEGS CASES TOTAL BARRELS 10 BARREL BREWING LLC 0.00 0.00 0.00 18TH STREET BREWERY LLC 0.00 0.00 0.00 3LB SAN MARCOS LLC 0.00 0.00 0.00 4 HANDS BREWING COMPANY LLC 0.00 0.00 0.00 51ST STATE BREWING CO. 0.00 0.00 0.00 7TH STREET BEER COMPANY LLC 0.00 0.00 0.00 ABITA BREWING COMPANY LLC 30.00 20.90 50.90 AGAINST THE GRAIN LLC 0.00 0.00 0.00 AIKO IMPORTERS INC 0.00 0.00 0.00 ALASKAN BREWING LLC 308.99 342.03 651.02 ALLAGASH BREWING CO 31.00 101.70 132.70 ALLSTATE LIQUOR & WINE COMPANY, INC. 0.00 0.00 0.00 ALLTECH'S BEVERAGE DIVISION LLC 80.67 94.35 175.02 ALMANAC BEER CO LLC 0.00 0.00 0.00 AMAZEN LLC 0.00 0.00 0.00 AMERICAN VINTAGE BEVERAGE INC. 0.00 757.76 757.76 AMIR PEAY 0.00 0.00 0.00 AMTEC INTERNATIONAL OF NY CORP 0.00 34.49 34.49 ANDREAS HILDEBRANDT 0.00 0.00 0.00 ANDREW FOX 0.00 0.00 0.00 ANHEUSER-BUSCH COMPANIES LLC 6,122.44 137,412.36 143,534.80 ARCADIA BEVERAGE COMPANY 0.00 0.00 0.00 ARTISANAL IMPORTS INC 14.45 12.81 27.26 ASAHI BEER U.S.A., INC. 0.00 25.43 25.43 ASLIN BEER COMPANY 0.00 0.00 0.00 ASSOCIATED BREWING COMPANY 0.00 108.20 108.20 ATHENEE IMPORTERS & DISTRIBUTORS LTD 0.00 0.00 0.00 AUGUST SCHELL BREWING CO 68.50 290.09 358.59 AUMAKUA HOLDINGS INC 0.00 0.00 0.00 AVENUE WINE AND LIQUOR, INC.