1980-1985 Ad

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fishery Management Plan for the Dutch Harbor Subdistrict State-Waters and Parallel Pacific Cod Seasons, 2021

Regional Information Report 4K20-12 Fishery Management Plan for the Dutch Harbor Subdistrict State-Waters and Parallel Pacific Cod Seasons, 2021 By Asia Beder December 2020 Alaska Department of Fish and Game Division of Commercial Fisheries Symbols and Abbreviations The following symbols and abbreviations, and others approved for the Système International d'Unités (SI), are used without definition in the following reports by the Divisions of Sport Fish and of Commercial Fisheries: Fishery Manuscripts, Fishery Data Series Reports, Fishery Management Reports, and Special Publications. All others, including deviations from definitions listed below, are noted in the text at first mention, as well as in the titles or footnotes of tables, and in figure or figure captions. Weights and measures (metric) General Mathematics, statistics centimeter cm Alaska Administrative all standard mathematical deciliter dL Code AAC signs, symbols and gram g all commonly accepted abbreviations hectare ha abbreviations e.g., Mr., Mrs., alternate hypothesis HA kilogram kg AM, PM, etc. base of natural logarithm e kilometer km all commonly accepted catch per unit effort CPUE liter L professional titles e.g., Dr., Ph.D., coefficient of variation CV meter m R.N., etc. common test statistics (F, t, χ2, etc.) milliliter mL at @ confidence interval CI millimeter mm compass directions: correlation coefficient east E (multiple) R Weights and measures (English) north N correlation coefficient cubic feet per second ft3/s south S (simple) r foot ft west W covariance cov gallon gal copyright degree (angular) ° inch in corporate suffixes: degrees of freedom df mile mi Company Co. expected value E nautical mile nmi Corporation Corp. -

Alaska Peninsula–Aleutian Islands (Dutch Harbor) Food and Bait Herring Fishery

Regional Information Report 4K20-06 Alaska Peninsula–Aleutian Islands Management Area Commercial Herring Fishery Management Strategy, 2020 by Cassandra J. Whiteside April 2020 Alaska Department of Fish and Game Divisions of Sport Fish and Commercial Fisheries Symbols and Abbreviations The following symbols and abbreviations, and others approved for the Système International d'Unités (SI), are used without definition in the following reports by the Divisions of Sport Fish and of Commercial Fisheries: Fishery Manuscripts, Fishery Data Series Reports, Fishery Management Reports, and Special Publications. All others, including deviations from definitions listed below, are noted in the text at first mention, as well as in the titles or footnotes of tables, and in figure or figure captions. Weights and measures (metric) General Mathematics, statistics centimeter cm Alaska Administrative all standard mathematical deciliter dL Code AAC signs, symbols and gram g all commonly accepted abbreviations hectare ha abbreviations e.g., Mr., Mrs., alternate hypothesis HA kilogram kg AM, PM, etc. base of natural logarithm e kilometer km all commonly accepted catch per unit effort CPUE liter L professional titles e.g., Dr., Ph.D., coefficient of variation CV meter m R.N., etc. common test statistics (F, t, 2, etc.) milliliter mL at @ confidence interval CI millimeter mm compass directions: correlation coefficient east E (multiple) R Weights and measures (English) north N correlation coefficient cubic feet per second ft3/s south S (simple) r foot ft west W covariance cov gallon gal copyright © degree (angular ) ° inch in corporate suffixes: degrees of freedom df mile mi Company Co. expected value E nautical mile nmi Corporation Corp. -

TABLE of CONTENTS Page

HISTORIC RESOURCES INVENTORY Unalaska, Alaska June 2016 HISTORIC RESOURCES INVENTORY UNALASKA, ALASKA Prepared for: City of Unalaska Planning Department and Historic Preservation Commission Prepared by: DOWL 4041 B Street Anchorage, Alaska 99503 (907) 562-2000 June 2016 Unalaska, Alaska Historic Resources Inventory June 2016 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS .............................................................................................................1 1.0 INTRODUCTION ...............................................................................................................3 1.1 Goals of the Project ...........................................................................................................3 1.2 Summary History of Previous Inventories and Plans .......................................................4 2.0 REGULATORY OVERVIEW ............................................................................................5 2.1 City of Unalaska Ordinance ..............................................................................................5 2.2 Alaska State Historic Preservation Act .............................................................................5 2.3 National Historic Preservation Act ...................................................................................6 2.4 Historic Sites, Building, and Antiquities Act ....................................................................8 3.0 METHODS ..........................................................................................................................9 -

Read More About Arctic and International Relations Series Here

Fall 2018, Issue 6 ISSN 2470-7414 Arctic and International Relations Series Bridging the Gap between Arctic Indigenous Communities and Arctic Policy: Unalaska, the Aleutian Islands, and the Aleut International Association EAST ASIA CENTER Contents PART 1: INTRODUCTIONS AND OVERVIEW 5 Bridging the Gap between Arctic Indigenous Communities and Arctic Policy: Unalaska, the Aleutian Islands, and the Aleut International Association Nadine Fabbi 6 South Korea’s Role as an Observer State on the Arctic Council and Its Contribution to Arctic Indigenous Societies 10 Minsu Kim Introduction to the Aleut International Association 16 Liza Mack Aleut vs. Unangan: Two Notes on Naming 18 Qawalangin Tribal Council of Unalaska Shayla Shaishnikoff PART 2: UNALASKA HISTORY AND ALEUT GOVERNANCE 21 Unalaska and Its Role in the Fisheries: Resources of the Bering Sea and Aleutian Islands 22 Frank Kelty The Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act, Tribes, and the Alaska National Interest Land Conservation Act 25 Liza Mack Qawalangin Tribal Council of Unalaska 30 Tom Robinson with Joanne Muzak Qawalangin Tribal Council of Unalaska’s Environmental Department 33 Chris Price with Joanne Muzak My Internship at the Qawalangin Tribe 37 Shayla Shaishnikoff A Brief History of Unalaska and the Work of the Ounalashka Corporation 38 Denise M. Rankin The Work of the Aleut International Association 41 Liza Mack PART 3: UNALASKA: PLACE AND PEOPLE 43 The Flora of Unalaska and Unangan Use of Plants 44 Sharon Svarny-Livingston Fresh, Delicious Lettuce in Unalaska: Meet Blaine and Catina -

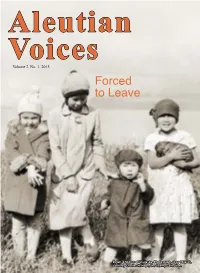

Aleutian Voices Volume 2, No

Aleutian Voices Volume 2, No. 1, 2015 Forced to Leave Detail: Children of Unalaska. Photograph, circa 1932-33, courtesy Charles H. Hope, the Svarny Collection. As the nation’s principal conservation agency, the Department of the Interior has responsibility for most of our nationally-owned public lands and natural and cultural resources. This includes fostering the wisest use of our land and water resources, protecting our fish and wildlife, preserving the environmental and cultural values of our national parks and historical places, and providing for enjoyment of life through outdoor recreation. The Cultural Resources Programs of the National Park Service have responsibilities that include stewardship of historic buildings, museum collections, archeological sites, cultural landscapes, oral and written histories, and ethnographic resources. Our mission is to identify, evaluate and preserve the cultural resources of the park areas and to bring an understanding of these resources to the public. Congress has mandated that we preserve these resources because they are important components of our national and personal identity. Published by the National Park Service, United States Department of the Interior, through the Government Printing Office with the assistance of Debra A. Mingeaud. During World War II the remote Aleutian Islands, home to the Unanga{ (Aleut) people for over 8,000 years, became one of the fiercely contested battlegrounds of the Pacific.This thousand-mile-long archipelago saw the first invasion of American soil since the War of 1812, a mass internment of American civilians, a 15-month air war, and one of the deadliest battles in the Pacific Theatre. In 1996 Congress designated the Aleutian World War II National Historic Area to interpret, educate, and inspire present and future generations about the history of the Unanga{ and the Aleutian Islands in the defense of the United States in World War II. -

Lost Villages of the Eastern Aleutians

Cupola from the Kashega Chapel in the Unalaska churchyard. Photograph by Ray Hudson, n.d. BIBLIOGRAPHY Interviews The primary interviews for this work were made in 2004 with Moses Gordieff, Nicholai Galaktionoff, Nicholai S. Lekanoff, Irene Makarin, and Eva Tcheripanoff. Transcripts are found in The Beginning of Memory: Oral Histories on the Lost Villages of the Aleutians, a report to the National Park Service, The Aleutian Pribilof Islands Restitution Fund, and the Ounalashka Corporation, introduced and edited by Raymond Hudson, 2004. Additional interviews and conversations are recorded in the notes. Archival Collections Alaska State Library Historical Collections. Samuel Applegate Papers, 1892-1925. MS-3. Bancroft Library Collection of manuscripts relating to Russian missionary activities in the Aleutian Islands, [ca. 1840- 1904] BANC MSS P-K 209. Hubert Howe Bancroft Collection Goforth, J. Pennelope (private collection) Bringing Aleutian History Home: the Lost Ledgers of the Alaska Commercial Company 1875-1897. Logbook, Tchernofski Station, May 5, 1887 – April 22, 1888 Library of Congress, Manuscript Division Russian Orthodox Greek Catholic Church of America, Diocese of Alaska Records, 1733-1938. National Anthropological Archives, Smithsonian Institution National Archives and Records Administration Record Groups 22 (Fish and Wildlife Service), 26 (Coast Guard), 36 (Customs Service), 75 (Bureau of 322 LOST VILLAGES OF THE EASTERN ALEUTIANS: BIORKA, KASHEGA, MAKUSHIN Indian Affairs) MF 720 (Alaska File of the Office of the Secretary of the Treasury, 1868-1903) MF Z13 Pribilof Islands Logbooks, 1870-1961. (Previous number A3303) Robert Collins Collection. (Private collection of letters and documents relating to the Alaska Commercial Company) Smithsonian Institution Archives Record Unit 7073 (William Healey Dall Collection) Record Unit 7176 (U.S. -

Stratigraphy and Depositional Environment of the Dutch Harbor Member of the Unalaska Formation, Unalaska Island, Alaska

Stratigraphy and Depositional Environment of the Dutch Harbor Member of the Unalaska Formation, Unalaska Island, Alaska By STEPHEN M. LANKFORD and JAMES M. HILL CONTRIBUTIONS TOSTRATIGRAPHY GEOLOGICAL SURVEY BULLETIN 1457-B Sedimentological characteristics and regional signzjicance of a Miocene coarse clastic turbidite on the Aleutian ridge UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON: 1979 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR CECIL D. ANDRUS, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY H. William Menard, Director Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Lankford, Stephen M. Stratigraphy and depositional environment of the Dutch Harbor Member of the Unalaska Formation, Unalaska Island, Alaska. (Contributions to stratigraphy) (Geological Survey Bulletin 1457-B) Bibliography: p. B 14. 1. Geology, Stratigraphic-Miocene. 2. Turbidities--Alaska-Unalaska Island. 3. Geology-Alaska-Unalaska Island. I. Hill, James M., joint author. 11. Title. 111. Series. IV. Series: United States. Geological Survey. Bulletin 1457-B QE75.B9 no. 1457-B [QE694] 557.3'08s 155 1.7'81 78-606 176 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U. S. Government Printing Office Washington, D. C. 20402 Stock Number 024-001-03 14 1-8 CONTENTS Page Abstract ........................................ B1 Introduction -__-_----_----------------------------- 1 Unalaska Formation ......................................... 3 Dutch Harbor Member ....................................... 4 Exposure and areal extent -_-___---_------------------------------------4 Lithology ............................................................. -

Growth of Historical Sitka Spruce Plantations at Unalaska Bay, Alaska

This file was created by scanning the printed publication. Text errors identified by the software have been corrected; however, some errors may remain. United States Department of Agriculture Growth of Historical Forest Service Pacific Northwest Sitka Spruce Plantations Research Station General Technical Report at Unalaska Bay, Alaska PNW-GTR-236 April 1989 J. Alden and D. Bruce Authors J. ALDEN is a forest geneticist, Institute of Northern Forestry, 308 Tanana Drive, Fairbanks, Alaska 99775-5500. D. BRUCE is a mensurationist (retired, currently a volunteer), Forestry Sciences Laboratory, P.O. Box 3890, Portland, Oregon 97208-3890. Abstract Alden, J.; Bruce, D. 1989. Growth of historical Sitka spruce plantations at Unalaska Bay, Alaska. Gen. Tech. Rep. PNW-GTR-236. Portland, OR: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Pacific Northwest Experiment Station. 18 p. Sitka spruce (Picea sitchensis (Bong.) Carr.) grew an estimated 37 cubic feet of stem- wood per acre per year (2.6 m3·ha-1·yr-1) in remnant World War II plantations on Amaknak Island and 38 cubic feet of stemwood per acre per year (2.7 m3·ha-1·yr-1) in an early 19th century grove on Expedition Island, 520 miles (837 km) southwest of natural tree limits in Alaska. Trees in fairly dense plots on Amaknak Island averaged 7 inches (18 cm) in diameter at breast height (d.b.h.) and 21 feet (6.5 m) tall on sheltered sites. The largest trees in the Expedition Island grove were 21.5 inches (54.6 cm) in d.b.h. and 55 feet (16.8 m) tall. -

Unalaska Port of Dutch Harbor Wildlife Viewing Guide

ildlife W ur O atch W visitor center at 5 Broadway Street. Street. Broadway 5 at center visitor V i s i & All other photos ©ADF&G. photos other All t o n r o s i t Fish and Game and Fish visiting Unalaska, stop by the the by stop Unalaska, visiting Williams • Whale / Fox ©Ali Bonomo • Emperor goose / Seal ©Suzi Golodoff ©Suzi Seal / goose Emperor • Bonomo ©Ali Fox / Whale • Williams B n u e Crested auklets / Seacoast ©Dan Parrett • Sunset flowers ©Richard Bye • Otter ©Jim ©Jim Otter • Bye ©Richard flowers Sunset • Parrett ©Dan Seacoast / auklets Crested r v e n info or call (877)581-2612. While While (877)581-2612. call or info a Photos Alaska Department of of Department Alaska o u C Bureau. Visit www.unalaska. Visit Bureau. − − U r Harbor Convention and Visitors Visitors and Convention Harbor n www.wildlifeviewing.alaska.gov o a b l a r s a k H consult the Unalaska, Port of Dutch Dutch of Port Unalaska, the consult a , h c P t o u r D t f o For information on tours and lodging, lodging, and tours on information For interesting land animals inhabit these lands and waters. waters. and lands these inhabit animals land interesting visit www.wildlifeviewing.alaska.gov. www.wildlifeviewing.alaska.gov. visit For more information on wildlife viewing across Alaska, Alaska, across viewing wildlife on information more For the world, bountiful fish and marine mammals and several several and mammals marine and fish bountiful world, the Opportunities to see wildlife abound. Birds from all over over all from Birds abound. -

Attu the Forgotten Battle

ATTU THE FORGOTTEN BATTLE John Haile Cloe soldiers, Attu Island, May 14, 1943. (U.S. Navy, NARA 2, RG80G-345-77087) U.S. As the nation’s principal conservation agency, the Department of the Interior has responsibility for most of our nationally owned public lands and natural and cultural resources. This includes fostering the wisest use of our land and water resources, our national parks and historical places, and providing for enjoyment of life through outdoorprotecting recreation. our fish and wildlife, preserving the environmental and cultural values of The Cultural Resource Programs of the National Park Service have responsibilities that include stewardship of historic buildings, museum collections, archeological sites, cultural landscapes, oral and written histories, and ethnographic resources. Our mission is to identify, evaluate and preserve the cultural resources of the park areas and to bring an understanding of these resources to the public. Congress has mandated that we preserve these resources because they are important components of our national and personal identity. Study prepared for and published by the United State Department of the Interior through National Park Servicethe Government Printing Office. Aleutian World War II National Historic Area Alaska Affiliated Areas Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author and contributors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Department of the Interior. Attu, the Forgotten Battle ISBN-10:0-9965837-3-4 ISBN-13:978-0-9965837-3-2 2017 ATTU THE FORGOTTEN BATTLE John Haile Cloe Bringing down the wounded, Attu Island, May 14, 1943. (UAA, Archives & Special Collections, Lyman and Betsy Woodman Collection) TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF PHOTOGRAPHS .........................................................................................................iv LIST OF MAPS ......................................................................................................................... -

City of Unalaska, International Port of Dutch Harbor, Alaska Page 1

CITY OF UNALASKA International Port of Dutch Harbor Alaska Controller 43 Raven Way · P. O. Box 610 · Unalaska, Alaska 99685 (907) 581-1251 · www.ci.unalaska.ak.us Comptroller - City of Unalaska, International Port of Dutch Harbor, Alaska Page 1 WHY APPLY? Unalaska is the anchor for commercial fishing activity in the Bering Sea and the Aleutian Islands and is the The City of Unalaska is a well-financed and #1 commercial fishing port in the United States, professionally run organization, staffed by based on the quantity of the catch, a distinction held hardworking, talented and successful people. City for more than 20 years. facilities are well-maintained, and we have a history of numerous and successful capital projects. This Unalaska is also the home of the western-most position will provide many challenges and the container terminal in the United States and is one of opportunity to grow professionally. the most productive ports for transshipment of cargo in Alaska. In addition to product shipped COMMUNITY PROFILE domestically to and from this regional hub, product is shipped to ports around the world with weekly The City of Unalaska is located on an island of the shipments headed to Europe and Asia by container same name, located in the Aleutian Chain off the ship and freighter. west coast of Alaska. We are 800 miles southwest of Unalaska is unique among Alaska’s coastal Anchorage, which is a 3 hour flight, and have a communities in the support services provided. In population of about 4,700. Our community is a addition to the five seafood processing facilities in vibrant mix of industry and history connected by 40 Unalaska, the business community provides a wide miles of roads linking our port, harbors and private range of support services including accounting and docks with local businesses and our thriving bookkeeping, banking, cold storage, construction residential community. -

The Alaska Peninsula-Aleutian Islands (Dutch Harbor) Herring Food and Bait Fishery

Fishery Management Report No. 10-14 Dutch Harbor Herring Food and Bait Fisheries Management Plan, 2010, and Alaska Peninsula-Aleutian Islands Management Area Herring Sac Roe and Food and Bait Fisheries Management Plan, 2010 by Alex C. Bernard April 2010 Alaska Department of Fish and Game Divisions of Sport Fish and Commercial Fisheries Symbols and Abbreviations The following symbols and abbreviations, and others approved for the Système International d'Unités (SI), are used without definition in the following reports by the Divisions of Sport Fish and of Commercial Fisheries: Fishery Manuscripts, Fishery Data Series Reports, Fishery Management Reports, and Special Publications. All others, including deviations from definitions listed below, are noted in the text at first mention, as well as in the titles or footnotes of tables, and in figure or figure captions. Weights and measures (metric) General Measures (fisheries) centimeter cm Alaska Administrative fork length FL deciliter dL Code AAC mideye to fork MEF gram g all commonly accepted mideye to tail fork METF hectare ha abbreviations e.g., Mr., Mrs., standard length SL kilogram kg AM, PM, etc. total length TL kilometer km all commonly accepted liter L professional titles e.g., Dr., Ph.D., Mathematics, statistics meter m R.N., etc. all standard mathematical milliliter mL at @ signs, symbols and millimeter mm compass directions: abbreviations east E alternate hypothesis HA Weights and measures (English) north N base of natural logarithm e cubic feet per second ft3/s south S catch per unit effort CPUE foot ft west W coefficient of variation CV gallon gal copyright © common test statistics (F, t, χ2, etc.) inch in corporate suffixes: confidence interval CI mile mi Company Co.