RE: Submission to the Senate Inquiry Into Shark Mitigation and Deterrent Measures

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NPOA Sharks Booklet.Indd

National Plan of Action for the Conservation and Management of Sharks (NPOA-Sharks) November 2013 South Africa Department of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries Private Bag X2, Rogge Bay, 8012 Tel: 021 402 3911 Fax: +27 21 402 3364 www.daff.gov.za Design and Layout: FNP Communications and Gerald van Tonder Photographs courtesy of: Department of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries (DAFF), Craig Smith, Charlene da Silva, Rob Tarr Foreword South Africa’s Exclusive Economic Zone is endowed with a rich variety of marine living South Africa is signatory to the Code of Conduct for Responsible Fisheries – voluntarily agreed to by members of the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) – and, as such, is committed to the development and implementation of National Plans of Action (NPOAs) as adopted by the twenty-third session of the FAO Committee on Fisheries in February 1999 and endorsed by the FAO Council in June 1999. Seabirds – aimed at reducing incidental catch and promoting the conservation of seabirds Fisheries and now regularly conducts Ecological Risk Assessments for all the commercial practices. Acknowledging the importance of maintaining a healthy marine ecosystem and the possibility of major detrimental effects due to the disappearance of large predators, South from the list of harvestable species. In accordance with international recommendations, South Africa subsequently banned the landing of a number of susceptible shark species, including oceanic whitetip, silky, thresher and hammerhead sharks. improves monitoring efforts for foreign vessels discharging shark products in its ports. To ensure long-term sustainability of valuable, but biologically limited, shark resources The NPOA-Sharks presented here formalises and streamlines ongoing efforts to improve conservation and management of sharks caught in South African waters. -

Shark Catch Trends and Effort Reduction in the Beach Protection Program, Kwazulu-Natal, South Africa (Elasmobranch Fisheries - Oral)

NOT TO BE CITED WITHOUT PRIOR REFERENCE TO THE AUTHOR(S) Northwest Atlantic Fisheries Organization Serial No. N4746 NAFO SCR Doc. 02/124 SCIENTIFIC COUNCIL MEETING – SEPTEMBER 2002 Shark Catch Trends and Effort Reduction in the Beach Protection Program, KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa (Elasmobranch Fisheries - Oral) S.F.J. Dudley Natal Sharks Board, P. Bag 2, Umhlanga Rocks, 4320, South Africa E-mail: [email protected] Abstract Shark nets have been set off the beaches of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa, since 1952, to minimise risk of shark attack. Reliable catch data for each of the 14 shark species commonly caught are available from 1978 only. The nets fish in fixed localities very close to shore and there is an absence of fisheries independent data for most species. There is uncertainty about factors such as localised stock depletion and philopatry. Catch rates of seven species show a significant decline, but this figure drops to four with the exclusion of the confounding effects of the annual sardine run. Of the four, two are caught in very low numbers (Java Carcharhinus amboinensis and great hammerhead Sphyrna mokarran) and it is probable that any decline in population size reflects either local depletion or additional exploitation elsewhere. The other two species (blacktip C. limbatus and scalloped hammerhead S. lewini) are caught in greater numbers. C. limbatus appears to have been subject to local depletion. Newborn S. lewini are captured by prawn trawlers and discarded, mostly dead, adding to pressure on this species. As a precautionary measure, and in the absence of clarity on the question of stock depletion, in September 1999 a process of reducing the number of nets per installation was begun, with a view to reducing catches. -

The Great Barrier Reed Marine Parks Shark Control Program

Public information package The Great Barrier Reef Marine Parks Shark Control Program Associated with application G33288.1 Applicant: State of Queensland Department of Agriculture and Fisheries GPO Box 46 Brisbane QLD 4001 All comments and submissions to: Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority Assessments and Permissions Team PO Box 1379 Townsville QLD 4810 Email: [email protected] Website: www.gbrmpa.gov.au/about-us/consultation Contents Introduction.......................................................................................................................................... 3 The Application ................................................................................................................................... 4 Program apparatus ......................................................................................................................... 4 Nets ................................................................................................................................................. 4 Drumlines ........................................................................................................................................ 5 Servicing apparatus ........................................................................................................................ 5 Proposed apparatus per location/beach within the GBRMPs ......................................................... 6 Management and mitigation strategies .............................................................................................. -

A Historical Overview of the Origins of Anti-Shark Measures in Natal, 1940 - 1980

A HISTORICAL OVERVIEW OF THE ORIGINS OF ANTI-SHARK MEASURES IN NATAL, 1940 - 1980 Melissa Joyce van Oordt A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Master of Arts University of KwaZulu-Natal, Howard College 2006 I declare that this thesis has not been submitted to any other university and that it is my entirely own work and that I have given due acknowledgement of all sources. Melissa Joyce van Oordt Supervisor Copyright by Melissa Joyce van Oordt 2006 © Table of Contents Abstract III Acknowledgments iv - vi Figures and Illustrations vii Abbreviations viii Prologue The emergence of beach recreation and anti-shark measures in Natal: 1900s - 1957 "Caution"l 1 - 16 Chapter One "Black December", Myths, Fear and Sharks "Undoubtedly it is a man-killer.,,2 17 - 48 Chapter Two Post-War Beach Recreation off the Natal coastline and the establishment of shark research institutions in Natal I Pietermaritzburg Archives Repository (PAR), Attorney General's Office (AGO) 1/8/47, 45A11895, 'Natal Water Police Point to The Attorney General: Superintendent of Water Police Reports on Danger of Sharks in Durban', 6th February 1895. 2 V. Coppleson. Shark Attack (Sydney: Angus and Robertson, 1988) originally published in 1958, p.2 on "Great Wh ites" 49 - 81 Chapter Three Anti-shark measures in Natal during the 1960s 82 -108 Chapter Four The 1970s, Anti-shark measures, Tourism, Media and Conservation 109 - 141 Conclusion 142 - 151 Bibliography 152 - 182 ABSTRACT This thesis studies the ongms of anti-shark measures in Natal, highlighting the relationship between beach recreation, anti-shark measures and the important influence of human perceptions of sharks. -

UNEP/CMS/MS/Inf/10 PRESENT STATUS of SHARK FISHING IN

UNEP/CMS/MS/Inf/10 PRESENT STATUS OF SHARK FISHING IN THE MARINE WATER OF BANGLADESH Abstract : The present study was done during the period April/2006 to March/2007. A total 22 species belongs to 17 genera and 11 families including sharks, skates and rays were identified. Out of this sharks comprises of 10 species, 08 genera belongs to 06 families. In the ray group 10 species, 07 genera and 05 families and 02 species of skates belongs to 02 genera and 01 family were identified. The total landed of sharks, skates and rays were 398.68 MT. The percentage composition should that the highest catch in percentage weight, Himantura uarnak was 41.11% and the lowest Amphotistius kuhlii which was 0.04%. The highest landing was in the month of June/06 was 81.935 MT and the lowest in the August/06 was 4.458 MT. *Bikram Jit Roy *Manju Prava Dey *Md. Fokhrul Alam *Niprandra Kumar Singha Scientific Officer, Marine Fisheries Survey Management Unite, C.G.O. Building-2, 6th Floor, Agrabad, Chittagong, Bangladesh. PRESENT STATUS OF SHARK FISHING IN THE MARINE WATER OF BANGLADESH Abstract : The present study was done during the period April/2006 to March/2007. A total 22 species belongs to 17 genera and 11 families including sharks, skates and rays were identified. Out of this sharks comprises of 10 species, 08 genera belongs to 06 families. In the rays group 10 species, 07 genera and 05 families and 02 species of skates belongs to 02 genera and 01 family were identified. -

Queensland Shark Control Program

Queensland Shark Control Program Queensland Shark Control Program Review of Alternative Approaches 59919123 Prepared for Qld Dept. Agriculture and Fisheries 20 September 2019 23 September 2019 Cardno i Queensland Shark Control Program Contact Information Document Information Cardno (NSW/ACT) Pty Ltd Prepared for Qld Dept. Agriculture and ABN 95 001 145 035 Fisheries Project Name Review of Alternative Level 9 - The Forum Approaches 203 Pacific Highway St Leonards NSW 2065 File Reference 59919123_Qld shark bite Australia control options review_ Cardno 20_9_19 www.cardno.com Rev_0.docx Phone +61 2 9496 7700 Fax +61 2 9439 5170 Job Reference 59919123 Date 20 September 2019 Version Number Rev 0 Author(s): Name: Craig Blount Effective Date 20/09/2019 Job title: Regional Senior Principal Approved By: Name: Marcus Lincoln Smith Date Approved 20/09/2019 Job title: Senior Principal Document History Version Effective Date Description of Revision Prepared by Reviewed by Rev A 12 September First draft for client Daryl McPhee, Craig Blount, Marcus Lincoln Smith 2019 review Will MacBeth, Dilys Zhang Rev 0 20 September Final for issue Daryl McPhee, Craig Blount, Marcus Lincoln Smith 2019 Will MacBeth, Dilys Zhang © Cardno. Copyright in the whole and every part of this document belongs to Cardno and may not be used, sold, transferred, copied or reproduced in whole or in part in any manner or form or in or on any media to any person other than by agreement with Cardno. This document is produced by Cardno solely for the benefit and use by the client in accordance with the terms of the engagement. -

Sharks (NPOA-Sharks) Foreword

National Plan of Action for the Conservation and Management of Sharks (NPOA-Sharks) Foreword South Africa’s Exclusive Economic Zone is endowed with a rich variety of marine living resources. The sustainable management of these resources for the benefit of all South Africans, present and future, remains a firm commitment of the South African Government. South Africa is signatory to the Code of Conduct for Responsible Fisheries - voluntarily agreed to by members of the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) - and, as such, is committed to the development and implementation of National Plans of Action (NPOAs) as adopted by the twenty- third session of the FAO Committee on Fisheries in February 1999 and endorsed by the FAO Council in June 1999. NPOAs describe strategies through which commercial fishing nations can achieve economically and ecologically sustainable fisheries. South Africa published the NPOA-Seabirds – aimed at reducing incidental catch and promoting the conservation of seabirds in longline fisheries - in August 2008. South Africa has adopted an Ecosystem Approach to Fisheries and now regularly conducts Ecological Risk Assessments for all the commercial fishing sectors, widely consulting with all stakeholders regarding best management practices. Acknowledging the importance of maintaining a healthy marine ecosystem and the possibility of major detrimental effects due to the disappearance of large predators, South Africa was the first country to offer full protection to the great white shark, removing it from the list of harvestable species. In accordance with international recommendations, South Africa subsequently banned the landing of a number of susceptible shark species, including oceanic whitetip, silky, thresher and hammerhead sharks. -

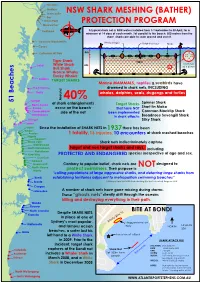

SHARK MESHING (BATHER) Bar Dixon Park PROTECTION PROGRAM Merewether

Stockton Nobbys Newcastle NSW SHARK MESHING (BATHER) Bar Dixon Park PROTECTION PROGRAM Merewether Redhead A typical shark net in NSW waters installed from 1st September to 30 April, for a minimum of 14 days of each month. Set parallel to the beach, 500 metres from the shore. Sharks are able to swim around and over it. Swansea-Blacksmiths Whale pinger Dolphin pinger Floats Caves Catherine Hill Bay 4m Tiger Shark 150m mesh size Lakes White Shark 6m Bull Shark 60 X 60 cm Bronze Whaler Dusky Whaler Soldiers TARGET SHARKS Marine MAMMALS, reptiles & seabirds have The Entrance drowned in shark nets, INCLUDING Shelly whales, dolphins, seals, dugongs and turtles Around 40% 51 Beaches Terrigal Spinner Shark North Avoca of shark entanglements Target Sharks Avoca occur on the beach that have NOT Short fin Mako Copacabana side of the net been implemented Common Blacktip Shark MacMasters in shark attacks Broadnose Sevengill Shark Killcare Silky Shark Umina Palm Since the installation of SHARK NETS in there has been Whale 1937 Avalon 1 fatality,16 injuries,10 encounters at shark meshed beaches Bilgola Newport Mona Vale Shark nets indiscriminately capture Warriewood North Narrabeen target and non target sharks and rays, including Narrabeen Dee Why PROTECTED AND ENDANGERED species irrespective of age and sex. Curl Curl Harbord Queenscliff Contrary to popular belief, shark nets are NOT designed to North Steyne Their purpose is: Manly protect swimmers. “culling populations of large aggressive sharks, and deterring large sharks from Bondi establishing territories adjacent to metropolitan swimming beaches” Bronte DPI Report into the NSW Shark Meshing (Bather Protection) Program 2009 Coogee Maroubra A number of shark nets have gone missing during storms. -

Sharks, Nets and More-Than-Human Territory in Eastern Australia Leah Maree Gibbs University of Wollongong, [email protected]

University of Wollongong Research Online Faculty of Social Sciences - Papers Faculty of Social Sciences 2018 Shores: Sharks, Nets and More-Than-Human Territory in Eastern Australia Leah Maree Gibbs University of Wollongong, [email protected] Publication Details Gibbs, L. (2018). Shores: Sharks, Nets and More-Than-Human Territory in Eastern Australia. In K. Peters, P. Steinberg & E. Stratford (Eds.), Territory Beyond Terra (pp. 203-219). London, United Kingdom: Rowman & Littlefield International. Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] Shores: Sharks, Nets and More-Than-Human Territory in Eastern Australia Abstract In Australia, for eight months of each year Sydney's most popular beaches are laced with fishing nets. Stretching 150 metres (492 feet) across, and set within 500 metres (1,640 feet) of the shore, the nets are anchored off fifty-one beaches between Newcastle in the north and Wollongong in the south. The aim of the Shark Meshing (Bather Protection) Program NSW is to reduce the risk of dangerous encounters between sharks and people, and specifically to deter sharks from establishing territories (Department of Primary Industries NSW 2009, 2015). Program managers achieve such ends by devising and deploying tools and employing people to catch and kill sharks. By considering what happens when non-human animals are enlisted in territorialising practices of shore control, this chapter examin es and unsettles the interplay between multiple interpretations of territory and the political implications of those interpretations. The orkw traces the state of New South Wales' Shark Meshing (Bather Protection) Program to understand how ter- ritory is claimed, asserted, and confounded at the shore. -

No. 46 No Shark Cull

Submission No 46 MANAGEMENT OF SHARKS IN NEW SOUTH WALES WATERS Organisation: No Shark Cull Inc Name: Ms Sharnie Connell Date Received: 22/10/2015 Parliamentary Enquiry into the Shark Management in NSW Submission by No Shark Cull Inc Written by Sharnie Connell Submitted 22nd October 2015 Executive Summary Shark attacks are incredibly rare events with less than 10 fatal incidents occurring worldwide on average per year. Shark bites occasionally occur in clusters in small localised areas causing fear in the population fuelled by sensationalist media reporting resulting in Government officials who feel that drastic action must be taken. Despite this there is little evidence to suggest that people significantly change their ocean based recreation activities and there is no negative impact on tourism to areas or beaches affected by recent shark incidents. Serious declines in the abundance of shark populations have been recorded with 90% having been removed from global the ocean ecosystem in the last 60 years. Due to biological factors such as sharks being slow growing, late to mature and having low reproduction rates recovery plans for white sharks have not been in place for long enough to have a positive impact on population levels. Increases in the rate of shark bite have been documented and are a direct result of human factors such as 50% global population increase, changes to the abundance and location of food sources and habitat change. Shark bites are most likely to be caused by mistaken identity, curiosity, self defence and dominance displays no evidence exists to justify common misconceptions of sharks as mindless killing machines, sharks are not attracted to human blood or certain colours, they do not defend territories or target people for food. -

Phylogeny of Lamniform Sharks Based on Whole Mitochondrial Genome Sequences

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 1-1-2003 Phylogeny of lamniform sharks based on whole mitochondrial genome sequences Toni Laura Ferrara Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Recommended Citation Ferrara, Toni Laura, "Phylogeny of lamniform sharks based on whole mitochondrial genome sequences" (2003). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 19960. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/19960 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Phylogeny of lamniform sharks based on whole mitochondrial genome sequences by Toni Laura Ferrara A thesis submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE Major: Zoology Program of Study Committee: Gavin Naylor, Major Professor Dean Adams Bonnie Bowen Jonathan Wendel Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 2003 11 Graduate College Iowa State University This is to certify that the master's thesis of Toni Laura Ferrara has met the thesis requirements of Iowa State University Signatures have been redacted for privacy 111 TABLE OF CONTENTS GENERAL INTRODUCTION 1 LITERATL:jRE REVIEW 2 CHAPTER ONE: THE BIOLOGY OF LAMNIFORM -

Should Nets and Drumlines Continue to Be Used to Protect Australians from Sharks? What They Said... the Issue at a Glance Backgr

Should nets and drumlines continue to be used to protect Australians from sharks? What they said... “There needs to be more drum lines immediately installed at Greenmount until the shark involved in the attack is found.” Queensland Opposition Leader Deb Frecklington “There's no such thing as a rogue shark. Unlike in the film Jaws nor in the early literature, there's no evidence sharks "get a taste for human flesh” ABC Environment reporter Nick Kilvert. The issue at a glance On September 8, 2020, a 46-year-old Gold Coast real estate agent, Nick Slater, was fatally mauled by a shark while surfing at Greenmount Beach. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2020- 09-09/shark-attack-gold-coast-greenmount-nick-slater/12643548 While there have been several fatal attacks in Queensland waters recently, no deaths have occurred off “protected” beaches such as Greenmount for more than twenty years. The beaches are protected mainly by shark nets and baited drumlines. Queensland Opposition leader Deb Frecklington called for more drumlines to be installed and for the shark to be found. However, Fisheries Minister Mark Furner said that there would be no hunt for the shark responsible for Mr Slater’s death. Instead, reliance on the system of nets and drumlines would continue. “We don’t hunt sharks, we put in material to protect swimmers,” Mr Furner told an ABC reporter. Queensland Premier Annastacia Palaszczuk said that if improvements could be made to the Queensland program, they should be. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2020-09-10/how-do-shark- nets-and-drum-lines-work-fatal-gold-coast-attack/12645488 Background Shark nets and drum lines A shark net is a submerged net placed around beaches to reduce shark attacks on swimmers.