No. 19, August 2008

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tourism, Arts & Culture Report

Armagh City Banbridge & Craigavon Borough TOURISM, ARTS & CULTURE REPORT AUGUST 2016 2 \\ ARMAGH CITY BANBRIDGE & CRAIGAVON BOROUGH INTRODUCTION The purpose of this document is to provide an overview of the topics relating to tourism, arts and culture in Armagh City, Banbridge and Craigavon Borough to help inform the development of a community plan. KEY FINDINGS Population (2014) Total Population by Age Population 15% 22% 0-15 years 205,711 16-39 years 40-64 years 32% 65+ years 11% of total 32% NI population Tourism Overnight trips (2015) 3% 0.1m of overnight trips 22m trips in Northern Ireland spent Place of Origin Reason for Visit 5% 5% 8% Great Britain Business 18% 34% North America Other 43% Northern Ireland Visiting Friends & Relatives ROI & Other Holiday/Pleasure/Leisure 5% 11% Mainland Europe 69% 2013 - 2015 Accomodation (2015) 1,173 beds Room Occupancy Rates Hotels 531 55% Hotels Bed & Breakfasts, Guesthouses 308 and Guest Accomodation 25% Self Catering 213 Other Commercial Accomodation Hostel 121 TOURISM, ARTS & CULTURE AUGUST 2016 // 3 Visitor Attractions (2015) Top three attractions 220,928visits 209,027visits 133,437visits Oxford Island National Kinnego Marina Lough Neagh Nature Reserve Discovery Centre Top three parks and gardens 140,074visits 139,435visits 126,123visits Edenvilla Park Tannaghmore Peatlands Park & Garden Gardens & Rare Breed Animal Farm Arts and Culture Engagement in Arts and Culture Arts Arts Used the public Visited a museum attendance participation library service or science centre Armagh City, Banbridge -

County Report

FOP vl)Ufi , NORTHERN IRELAND GENERAL REGISTER OFFICE CENSUS OF POPULATION 1971 COUNTY REPORT ARMAGH Presented pursuant to Section 4(1) of the Census Act (Northern Ireland) 1969 BELFAST : HER MAJESTY'S STATIONERY OFFICE PRICE 85p NET NORTHERN IRELAND GENERAL REGISTER OFFICE CENSUS OF POPULATION 1971 COUNTY REPORT ARMAGH Presented pursuant to Section 4(1) of the Census Act (Northern Ireland) 1969 BELFAST : HER MAJESTY'S STATIONERY OFFICE CONTENTS PART 1— EXPLANATORY NOTES AND DEFINITIONS Page Area (hectares) vi Population vi Dwellings vi Private households vii Rooms vii Tenure vii Household amenities viii Cars and garaging ....... viii Non-private establishments ix Usual address ix Age ix Birthplace ix Religion x Economic activity x Presentation conventions xi Administrative divisions xi PART II--TABLES Table Areas for which statistics Page No. Subject of Table are stated 1. Area, Buildings for Habitation and County 1 Population, 1971 2. Population, 1821-1971 ! County 1 3. Population 1966 and 1971, and Intercensal Administrative Areas 1 Changes 4. Acreage, Population, Buildings for Administrative Areas, Habitation and Households District Electoral Divisions 2 and Towns 5. Ages by Single Years, Sex and Marital County 7 Condition 6. Population under 25 years by Individual Administrative Areas 9 Years and 25 years and over by Quinquennial Groups, Sex and Marital Condition 7. Population by Sex, Marital Condition, Area Administrative Areas 18 of Enumeration, Birthplace and whether visitor to Northern Ireland 8. Religions Administrative Areas 22 9. Private dwellings by Type, Households, | Administrative Areas 23 Rooms and Population 10. Dwellings by Tenure and Rooms Administrative Areas 26 11. Private Households by Size, Rooms, Administrative Areas 30 Dwelling type and Population 12. -

Constituency Profile Newry and Armagh - January 2015

Constituency Profile Newry and Armagh - January 2015 Constituency Profile – Newry and Armagh January 2015 About this Report Welcome to the 2015 statistical profile of the Constituency of Newry and Armagh produced by the Research and Information Service (RaISe) of the Northern Ireland Assembly. The profile is based on the new Constituency boundary which came into force following the May 2011 Assembly elections. This report includes a demographic profile of Newry and Armagh and indicators of Health, Education, the Labour Market, Low Income, Crime and Traffic and Travel. For each indicator, this profile presents: ■ The most up-to-date information available for Newry and Armagh; ■ How Newry and Armagh compares with the Northern Ireland average; and, ■ How Newry and Armagh compares with the other 17 Constituencies in Northern Ireland. For a number of indicators, ward level data is provided demonstrating similarities and differences within the Constituency of Newry and Armagh. A summary table has been provided showing the latest available data for each indicator, as well as previous data, illustrating change over time. Please note that the figures contained in this report may not be comparable with those in previous Constituency Profiles as government Departments sometimes revise figures. Where appropriate, rates have been re-calculated using the most up-to-date mid-year estimates that correspond with the data. The data used in this report has been obtained from NISRAs Northern Ireland Neighbourhood Information Service (NINIS). To access the full range of information available on NINIS, please visit: http://www.ninis2.nisra.gov.uk i Constituency Profile – Newry and Armagh January 2015 This report presents a statistical profile of the Constituency of Newry and Armagh which comprises the wards shown below. -

Register of Employers 2021

REGISTER OF EMPLOYERS A Register of Concerns in which people are employed In accordance with Article 47 of the Fair Employment and Treatment (Northern Ireland) Order 1998 The Equality Commission for Northern Ireland Equality House 7-9 Shaftesbury Square Belfast BT2 7DP Tel: (02890) 500 600 E-mail: [email protected] August 2021 _______________________________________REGISTRATION The Register Under Article 47 of the Fair Employment and Treatment (Northern Ireland) Order 1998 the Commission has a duty to keep a Register of those concerns employing more than 10 people in Northern Ireland and to make the information contained in the Register available for inspection by members of the public. The Register is available for use by the public in the Commission’s office. Under the legislation, public authorities as specified by the Office of the First Minister and the Deputy First Minister are automatically treated as registered with the Commission. All other employers have a duty to register if they have more than 10 employees working 16 hours or more per week. Employers who meet the conditions for registration are given one month in which to apply for registration. This month begins from the end of the week in which the concern employed more than 10 employees in Northern Ireland. It is a criminal offence for such an employer not to apply for registration within this period. Persons who become employers in relation to a registered concern are also under a legal duty to apply to have their name and address entered on the Register within one month of becoming such an employer. -

988 Road Traffic and Vehicles No. 290 1978 No. 290 Made Coming

988 Road Traffic and Vehicles No. 290 1978 No. 290 ROAD TRAFFIC AND VEIDCLES Roads (Speed Limit) (No.2) Order (Northern Ireland) 1978 Made 27th September 1978 Coming into operation 4th December 1978 The Department of the Environment in exercise of the powers conferred by section 43(4) of the Road Traffic Act (Northern Ireland) 1970(a}(hereinafter referred to as "the Act") and now vested in itCb) and of every other power enabling it in that behalf hereby orders and direct~ as follows:- Citation and commencement 1. This Order may be cited as the Roads (Speed Limit) (No.2) Order . (Northern Ireland) 1978 and shall come into operation on 4th December 1978. Revocation of previous directions 2. The directions contained in article 2 of the Roads (Speed Limit) Order (Northern Ireland) 1956(c); article 4 of the Roads (Speed Limit) Order (Nor thern Ireland) 1960(d); article 3 of the Roads (Speed Limit) (No.2) Order (Northern Ireland) 1963(e); article 3 of the Roads (Speed Limit) (No.2) Order (Northern Ireland) 1964(f); article 3 of the Roads (Speed Limit) (No.2) Order (Northern Ireland) 1977(g) relative to the lengths of road specified in Schedule 1 are hereby revoked: . Speed restrictions on 'certain roads 3. Each of the roads specified in Schedule 2 shall be a r~stricted road for the p1ll"poses of section 43 of the Act for its. entire length except where other- wise indicated in Schedule 2. Sealed with the Official Seai of the Department of the. Environment for Northern Ireland on 27th September 1978. -

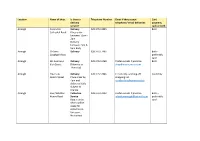

Location Name of Shop Is There a Delivery Service?

Location Name of shop Is there a Telephone Number Email if they accept Card delivery telephone/ email deliveries payment, service? cash or both Armagh Costcutter Delivery 028 3752 2885 Both Cathedral Road Place order between 11am - 2pm Delivery between 2pm & 5pm daily Armagh O’Kanes Delivery 028 3752 7985 Both- Loughgall Road preferably card Armagh Mc Anerneys Delivery 028 3752 2468 Prefer e-mails if possible Both Irish Street (Monday to [email protected] Thursday) Armagh Emersons Delivery 028 3752 2846 E-mail only- working off Card Only Scotch Street Place order by shopping list 4pm and [email protected] delivered daily Subject to change Armagh Spar/Whittles Collection 028 3752 2232 Prefer e-mails if possible Both – Newry Road Service [email protected] preferably Ring in order card which will be ready for collection in forecourt. No contact Armagh Mullans Delivery 028 3752 6300 Both- Monaghan Place order preferably Road between card. 9.30am-4.30pm Armagh Currans Spar Delivery 028 3752 3535 Both – Cathedral Road Preferably place preferably order by 3pm card Armagh Mace Delivery 028 3752 7527 Both Railway Street Place order by 1pm Annaghmore Annaghmore Delivery 028 3885 1201 Both – Spar preferably Derrycoose card Road Portadown Road Fruitfield Delivery 07747801242 [email protected] Cash and Portadown Road Delivering paypal within 3 mile transactions radius Specifically for older and vulnerable people Place order between 10am- 1pm Tandragee Spar Delivery and 028 3884 0097 Card Tandragee Collection Service Tandragee -

EONI-REP-223 - Streets - Streets Allocated to a Polling Station by Area Local Council Elections: 02/05/2019

EONI-REP-223 - Streets - Streets allocated to a Polling Station by Area Local Council Elections: 02/05/2019 LOCAL COUNCIL: ARMAGH, BANBRIDGE AND CRAIGAVON DEA: ARMAGH ST PETER'S PRIMARY SCHOOL, COLLEGELANDS, 90 COLLEGELANDS ROAD, CHARLEMONT, DUNGANNON, BT71 6SW BALLOT BOX 1/AR TOTAL ELECTORATE 810 WARD STREET POSTCODE N08000207 AGHINLIG COTTAGES, AGHINLIG, DUNGANNON BT71 6TD N08000207 AGHINLIG PARK, AGHINLIG, DUNGANNON BT71 6TE N08000207 AGHINLIG ROAD, AGHINLIG, DUNGANNON BT71 6SR N08000207 AGHINLIG ROAD, AGHINLIG, DUNGANNON BT71 6SP N08000207 ANNAHAGH ROAD, KILMORE, DUNGANNON BT71 7JE N08000207 ARMAGH ROAD, CORR AND DUNAVALLY, DUNGANNON BT71 7HY N08000207 ARMAGH ROAD, KEENAGHAN, DUNGANNON BT71 7HZ N08000207 ARMAGH ROAD, DRUMARN, DUNGANNON BT71 7HZ N08000207 ARMAGH ROAD, KILMORE, DUNGANNON BT71 7JA N08000207 CANARY ROAD, DERRYSCOLLOP, DUNGANNON BT71 6SU N08000207 CANARY ROAD, CANARY, DUNGANNON BT71 6SU N08000207 PORTADOWN ROAD, CHARLEMONT BORO, DUNGANNON BT71 7SE N08000207 COLLEGE LANDS ROAD, KISHABOY, DUNGANNON BT71 6SN N08000207 CHURCHVIEW, CHARLEMONT, DUNGANNON BT71 7SZ N08000207 DERRYGALLY ROAD, DERRYCAW, DUNGANNON BT71 6LZ N08000207 GARRISON PLACE, CHARLEMONT, DUNGANNON BT71 7SA N08000207 MAIN STREET, CHARLEMONT, MOY BT71 7SF N08000207 COLLEGE LANDS ROAD, CHARLEMONT BORO, MOY BT71 7SE N08000207 COLLEGE LANDS ROAD, KEENAGHAN, MOY BT71 6SN N08000207 COLLEGE LANDS ROAD, AGHINLIG, MOY BT71 6SW N08000207 CORRIGAN HILL ROAD, KEENAGHAN, DUNGANNON BT71 6SL N08000207 DERRYCAW ROAD, CANARY, DUNGANNON BT71 6SX N08000207 DERRYCAW ROAD, CANARY, -

ULSTER BANK Senior League Section 2 the Thomas Stewart Memorial Trophy

ULSTER BANK Senior League Section 2 The Thomas Stewart Memorial Trophy Winners 2011: Academy/Laurelvale/Templepatrick Section Secretary: George Whitten, 3 Hazelwood Park, Newtownabbey BT36 7QB (H) 9077 9977 (E) [email protected] 28 April 9 June Armagh v BISC Armagh v Saintfield Laurelvale v Portadown Academy v Cooke Collegians Millpark v Saintfield Millpark v Laurelvale Academy v Templepatrick Portadown v Drumaness BISC v Templepatrick 5 May Academy v Portadown 16 June BISC v Cooke Collegians Academy v Drumaness Drumaness v Laurelvale Portadown v BISC Millpark v Armagh Laurelvale v Armagh Saintfield v Templepatrick Millpark v Templepatrick Saintfield v Cooke Collegians 12 May Cooke Collegians v Millpark 23 June BISC v Drumaness Ireland v Australia (ODI) Stormont Laurelvale v Academy Closed date Portadown v Saintfield Templepatrick v Armagh 24 June Cooke Collegians v Drumaness 19 May Templepatrick v Academy Junior Cup 1st Round 30 June 26 May Academy v BISC Armagh v Portadown Armagh v Cooke Collegians BISC v Laurelvale Drumaness v Saintfield Drumaness v Millpark Portadown v Millpark Saintfield v Academy Templepatrick v Laurelvale Templepatrick v Cooke Collegians 7 July 2 June Armagh v Drumaness Armagh v Academy Cooke Collegians v Laurelvale BISC v Millpark Millpark v Academy Drumaness v Templepatrick Portadown v Templepatrick Laurelvale v Saintfield Saintfield v BISC Portadown v Cooke Collegians 14 July 18 August BISC v Armagh Cooke Collegians v Academy Drumaness v Cooke Collegians Templepatrick v BISC Portadown v Laurelvale Drumaness -

(Automatic Telling Machines) (Designation of Rural Areas) Order (Northern Ireland) 2006

STATUTORY RULES OF NORTHERN IRELAND 2006 No. 516 RATES The Rates (Automatic Telling Machines) (Designation of Rural Areas) Order (Northern Ireland) 2006 Made - - - - 13th December 2006 Coming into operation - 1st April 2007 The Department of Finance and Personnel(a) makes the following Order in exercise of the powers conferred by Article 42(1G) of the Rates (Northern Ireland) Order 1977(b): Citation and commencement 1. This Order may be cited as the Rates (Automatic Telling Machines) (Designation of Rural Areas) Order (Northern Ireland) 2006 and shall come into operation on 1st April 2007. Designation of rural areas 2. Wards as set out in the Schedule are designated as rural areas for the purposes of Article 42(1F) of the Rates (Northern Ireland) Order 1977. Sealed with the Official Seal of the Department of Finance and Personnel on 13th December 2006 Brian McClure A senior officer of the Department of Finance and Personnel (a) Formerly the Department of Finance; see S.I. 1982/338 (N.I. 6) Article 3 (b) S.I. 1977/2157 (N.I. 28); Article 42 was amended by Article 25 of the Rates (Amendment) (Northern Ireland) Order 2006 (S.I. 2006/2954 (N.I. 18)) SCHEDULE Article 2 List of Designated Rural Areas District Wards Derry Banagher Claudy Eglinton Limavady Magilligan Dungiven Gresteel Upper Glenshane The Highlands Ballykelly Feeny Glack Coleraine Kilrea Castlerock Garvagh Agivey Macosquin Dunluce Ringsend Ballymoney Benvardin Knockaholet Clogh Mills Dervock The Vow Killoquin Upper Stranocum Killoquin Lower Ballyhoe and Dunloy Corkey Moyle Bushmills -

Early Quaker Records in Co Armagh

Early Quaker Records in County Armagh_Layout 1 23/10/2013 10:42 Page 1 POYNTZPASS AND DISTRICT LOCAL HISTORY SOCIETY 71 EARLY QUAKER RECORDS IN COUNTY ARMAGH BY ROSS CHAPMAN Friends house - Moyallon built 1736 n these parts, the 1600’s were a time of turmoil, unsettled lands being resettled, new laws and ways of worship being introduced, land ownership being Ichanged. The seeds of discord were being sown. A century later when Poyntzpass was coming into being, its three main streets tell us of the three strands that make up the character of Ulster. These streets are Church Street, Chapel Street and Meeting Street, representing the English Protestant (Church), the Irish Catholic (Chapel), and Scottish Presbyterian (Meeting) roots. In Armagh City, the three strands are named English, Irish and Scotch streets and they are good reminders of the way that those identities grew up side by side. But history is not as simple and tidy as that! For among those who came from the north of England and settled in County Armagh were some who did not fit into any of the three main categories. At that time in the 1650’s this county was part of a Republic under Oliver Cromwell. Church and government were developing in a way which left some unsatisfied and disillusioned. A few men and women preachers came, travelling through towns and villages, to give a different slant on Christianity, distinct from each of the three main strands. They called themselves ‘friends’, as Christ said to his followers, “I call you not servants, but friends”,(John 15:15) so these pioneers took up the calling of being ‘Friends’. -

Constituency Profile

CCoonnssttiittuueennccyy PPrrooffiillee NNeewwrryy aanndd AArrmmaagghh September 2010 Using the latest data available through the Northern Ireland Neighbourhood Information Service (NINIS) www.ninis.nisra.gov.uk, this report provides an up-to-date statistical profile of the Constituency of Newry and Armagh. It includes information on the demographics of people living in Newry and Armagh as well as key indicators of Health, Education, the Economy, Employment, Housing, Crime and Poverty. For each indicator, this profile presents: • The most up-to-date information available for Newry and Armagh; • How this compares with Northern Ireland as a whole; • The ranking of the Constituency; and • Information on the lowest and highest ranking wards where available. This report presents a statistical profile of the Constituency of Newry and Armagh which comprises of the 39 wards shown below. 0 Charlemount 13 The Mall 26 Drumgullion 1 Loughgall 14 Milford 27 Windsor Hill 2 Hockley 15 Killeen 28 Ballybot 3 Ballymartrim 16 Downs 29 Derrymore 4 Tandragee 17 Demesne 30 St Patricks’ 5 Rich Hill 18 Markethill 31 Daisy Hill 6 Laurelvale 19 Carrigatuke 32 St Marys’ 7 Hamiltonsbawn 20 Derrynoose 33 Drumalane 8 Observatory 21 Tullyhappy 34 Fathom 9 Abbey Park 22 Keady 35 Silver Bridge 10 Killylea 23 Newtownhamilton 36 Creggan 11 Callan Bridge 24 Bessbrook 37 Forkhill 12 Poyntz Pass 25 Camlough 38 Crossmaglen 2 NEWRY AND ARMAGH: KEY FACTS Demographics • An estimated 110,033 people live in Newry and Armagh, the Constituency with the 4 th highest population in 2008. • The majority (67.2%) of people living in Newry and Armagh are of Catholic community background. -

The Abbey Christian Brothers’ Grammar School, Newry

The Abbey Christian Brothers’ Grammar School, Newry A guide for prospective parents and pupils The Abbey :: Christian Brothers’ Grammar School :: :: Prospectus :: 2011 Headmaster’s Welcome Abbey Christian Brothers’ Grammar School I am delighted that you have taken the 77A Ashgrove Rd time to get to know our school and I NEWRY BT34 1QN welcome you warmly. We are a school Telephone: Newry (028) 30263142 which has traditionally served the whole Fax: Newry (028) 30262514 E-mail: [email protected] Newry, South Down and South Armagh Website: www.abbeycbs.co.uk area and are very proud of our traditions Headmaster: Mr. D. H. J. McGovern BEd, MEd and our heritage. Contents Voluntary Grammar Denominational 2011 sees the Abbey in a very strong position having Boys successfully completed the move to our wonderful new building Age Range 11-19 and expansive site and again having its academic and non Headmaster’s Welcome .......................................................1 Careers Education, Information, Advice academic successes publicised on a national level. Background ..............................................................................2 and Guidance .......................................................................13 Enrolment Sept 2010: 880 Expected Enrolment Sept 2011: 890 New School Project ...............................................................2 Parental Links ......................................................................13 I hope that there are three elements of our school which Approved Admissions Number