Internalized Gender Roles and the Gothic in Native American

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fools Crow, James Welch

by James Welch Model Teaching Unit English Language Arts Secondary Level with Montana Common Core Standards Written by Dorothea M. Susag Published by the Montana Office of Public Instruction 2010 Revised 2014 Indian Education for All opi.mt.gov Cover: #955-523, Putting up Tepee poles, Blackfeet Indians [no date]; Photograph courtesy of the Montana Historical Society Research Center Photograph Archives, Helena, MT. by James Welch Model Teaching Unit English Language Arts Secondary Level with Montana Common Core Standards Written by Dorothea M. Susag Published by the Montana Ofce of Public Instruction 2010 Revised 2014 Indian Education for All opi.mt.gov #X1937.01.03, Elk Head Kills a Buffalo Horse Stolen From the Whites, Graphite on paper, 1883-1885; digital image courtesy of the Montana Historical Society, Helena, MT. Anchor Text Welch, James. Fools Crow. New York: Viking/Penguin, 1986. Highly Recommended Teacher Companion Text Goebel, Bruce A. Reading Native American Literature: A Teacher’s Guide. National Council of Teachers of English, 2004. Fast Facts Genre Historical Fiction Suggested Grade Level Grades 9-12 Tribes Blackfeet (Pikuni), Crow Place North and South-central Montana territory Time 1869-1870 Overview Length of Time: To make full use of accompanying non-fiction texts and opportunities for activities that meet the Common Core Standards, Fools Crow is best taught as a four-to-five week English unit—and history if possible-- with Title I support for students who have difficulty reading. Teaching and Learning Objectives: Through reading Fools Crow and participating in this unit, students can develop lasting understandings such as these: a. -

Notes for the Downloaders

NOTES FOR THE DOWNLOADERS: This book is made of different sources. First, we got the scanned pages from fuckyeahradicalliterature.tumblr.com. Second, we cleaned them up and scanned the missing chapters (Entering the Lives of Others and El Mundo Zurdo). Also, we replaced the images for new better ones. Unfortunately, our copy of the book has La Prieta, from El Mundo Zurdo, in a bad quality, so we got it from scribd.com. Be aware it’s the same text but from another edition of the book, so it has other pagination. Enjoy and share it everywhere! Winner0fThe 1986 BEFORECOLTJMBUS FOTJNDATION AMERICANBOOK THIS BRIDGE CALLED MY BACK WRITINGS BY RADICAL WOMEN OF COLOR EDITORS: _ CHERRIE MORAGA GLORIA ANZALDUA FOREWORD: TONI CADE BAMBARA KITCHEN TABLE: Women of Color Press a New York Copyright © 198 L 1983 by Cherrie Moraga and Gloria Anzaldua. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced without permission in writing from the publisher. Published in the United States by Kitchen Table: Women of Color Press, Post Office Box 908, Latham, New York 12110-0908. Originally published by Peresphone Press, Inc. Watertown, Massachusetts, 1981. Also by Cherrie Moraga Cuentos: Stories by Latinas, ed. with Alma Gomez and Mariana Romo-Carmona. Kitchen Table: Women of Color Press, 1983. Loving in the War Years: Lo Que Nunca Paso Por Sus Labios. South End Press, 1983. Cover and text illustrations by Johnetta Tinker. Cover design by Maria von Brincken. Text design by Pat McGloin. Typeset in Garth Graphic by Serif & Sans, Inc., Boston, Mass. Second Edition Typeset by Susan L. -

The Art of Hybridization-James Welch's Fools Crow

The Art of Hybridization-James Welch's Fools Crow Hans Bak University of Nijmegen Recent Native American fiction has yielded a particularly hybrid mode of realism, one fluid and flexible enough to accommodate elements from tribal lore and, in varying modes and degrees, an awareness of the epis- temological dilemmas of postmodernism. The injection of tribal ele- ments-shamanism, spirits, witchcraft, charms, love medicines-together with the use of a non-Western (cyclical rather than linear) concept of time, for example, help to account for the vaunted "magical" realism in the work of Louise Erdrich (Love Medicine and Tracks) or the radically subversive and unambiguously postmodernist revision of American history and Western myth in Gerald Vizenor's The Heirs of Columbus. As critics have recurrently suggested, Native American fiction which seeks to connect itself to the oral tradition of tribal narrative (as Vizenor in his use of trickster myths and the "stories in the blood") more natu- rally accommodates itself to a postmodernist approach to fiction than to a traditional realistic one.1 The oral tradition, then, might be seen as by nature antithetical to realism. As Paula Gunn Allen has also noted, for the contemporary Native writer loyalty to the oral tradition has been "a major force in Indian resistance" to the dominant culture. By fostering an awareness of tribal identity, spiritual traditions, and connection to the 1 See, for example, Paula Gunn Allen, The Sacred Hoop: Recovering the Feminine in American Indian Traditions (Boston: Beacon Press, 1986), Brian Swann and Arnold Krupat, eds., Recovering the Word: Essays on Native American Literature (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1987), and Gerald Vizenor, Narrative Chance: Postmodern Discourse on Native American Indian Literatures (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1989). -

Honouring Indigenous Writers

Beth Brant/Degonwadonti Bay of Quinte Mohawk Patricia Grace Ngati Toa, Ngati Raukawa, and Te Ati Awa Māori Will Rogers Cherokee Nation Cheryl Savageau Abenaki Queen Lili’uokalani Kanaka Maoli Ray Young Bear Meskwaki Gloria Anzaldúa Chicana Linda Hogan Chickasaw David Cusick Tuscarora Layli Long Soldier Oglala Lakota Bertrand N.O. Walker/Hen-Toh Wyandot Billy-Ray Belcourt Driftpile Cree Nation Louis Owens Choctaw/Cherokee Janet Campbell Hale Coeur d’Alene/Kootenay Tony Birch Koori Molly Spotted Elk Penobscot Elizabeth LaPensée Anishinaabe/Métis/Irish D’Arcy McNickle Flathead/Cree-Métis Gwen Benaway Anishinaabe/Cherokee/Métis Ambelin Kwaymullina Palyku Zitkala-Ša/Gertrude Bonnin Yankton Sioux Nora Marks Dauenhauer Tlingit Gogisgi/Carroll Arnett Cherokee Keri Hulme Kai Tahu Māori Bamewawagezhikaquay/Jane Johnston Schoolcraft Ojibway Rachel Qitsualik Inuit/Scottish/Cree Louis Riel Métis Wendy Rose Hopi/Miwok Mourning Dove/Christine Quintasket Okanagan Elias Boudinot Cherokee Nation Sarah Biscarra-Dilley Barbareno Chumash/Yaqui Kateri Akiwenzie-Damm Anishinaabe Dr. Charles Alexander Eastman/ Ohíye S’a Santee Dakota Witi Ihimaera Māori Esther Berlin Diné Lynn Riggs Cherokee Nation Arigon Starr Kickapoo Dr. Carlos Montezuma/Wassaja Yavapai Marilyn Dumont Cree/Métis Woodrow Wilson Rawls Cherokee Nation Ella Cara Deloria/Aŋpétu Wašté Wiŋ Yankton Dakota LeAnne Howe Choctaw Nation Simon Pokagon Potawatomi Marie Annharte Baker Anishinaabe John Joseph Mathews Osage Gloria Bird Spokane Sherwin Bitsui Diné George Copway/Kahgegagahbowh Mississauga Chantal -

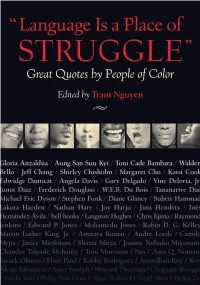

"Language Is a Place of Struggle" : Great Quotes by People of Color

“Language Is a Place of STRUGGLE” “Language Is a Place of STRUGGLE” Great Quotes by People of Color Edited by Tram Nguyen Beacon Press, Boston A complete list of quote sources for “Language Is a Place of Struggle” can be located at www.beacon.org/nguyen Beacon Press 25 Beacon Street Boston, Massachusetts 02108-2892 www.beacon.org Beacon Press books are published under the auspices of the Unitarian Universalist Association of Congregations. © 2009 by Tram Nguyen All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America 12 11 10 09 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 This book is printed on acid-free paper that meets the uncoated paper ANSI/NISO specifications for permanence as revised in 1992. Text design by Susan E. Kelly at Wilsted & Taylor Publishing Services Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Language is a place of struggle : great quotes by people of color / edited by Tram Nguyen. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-0-8070-4800-9 (hardcover : alk. paper) 1. Minorities—United States—Quotations. 2. Immigrants—United States—Quotations. 3. United States—Race relations—Quotations, maxims, etc. 4. United States—Ethnic relations—Quotations, maxims, etc. 5. United States—Social conditions—Quotations, maxims, etc. 6. Social change—United States—Quotations, maxims, etc. 7. Community life—United States—Quotations, maxims, etc. 8. Social justice—United States— Quotations, maxims, etc. 9. Spirituality—Quotations, maxims, etc. I. Nguyen, Tram. E184.A1L259 2008 305.8—dc22 2008015487 Contents Foreword vii Chapter 1 Roots -

FP 3.4 1983.Pdf (3.214Mb)

a current listing of contents Volume 3, Number 4,1983 Published by Susan Searing, Women's Studies Librarian-at-Large, University of Wisconsin System 112A Memorial Library 728 State Street Madison, Wisconsin 53706 (608) 263-5754 a current listins of contents Volume 3, Number 4, 1983 Periodical literature is the cutting edge of women's scholarship, feminist theory, and much of women's culture. Feminist Periodicals : A Current Listinq of Contents is publ ished by the Office of the Women's Studies Librarian-at-Large on a quarterly basis with the intent of increasing public awareness of feminist periodicals. It is our hope that Feminist Periodicals will serve several purposes: to keep the reader abreast of current topics in feminist literature; to increase readers' familiarity with a wide spectrum of feminist periodicals; and to pro- vide the requisite bibliographic information should a reader wjsh to subscribe to a journal or to obtain a particular article at her 1ibrary or through inter1ibrary loan. (Users will need to be aware of the limitations of the new copyright law with regard to photocopying of copyrighted materials. ) Table of contents paqes from current issues of major feminist journals are reproduced in each issue of Feminist ~eriodi cal s , preceded- by a comprehensive annotated listinq of a1 1 journals we have selected, As publ ication schedules vary enormously , not every periodical wi 11 have table of contents pages reproduced in each issue of FP. The annotated 1isting provides the following information on each journal : Year of first publ ication. Frequency of publication. U.S. subscription price(s) . -

The Exiled Native. Questions of Cultural Removal and Translocal

Philipp Kneis; Universität Potsdam, Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin The Exiled Native. Questions of Cultural Removal and Translocal American Indian Identity in Novels by Sherman Alexie and James Welch Presentation at the conference “Postcolonial Translocations” (GNEL 20), Münster, May 21–24, 2009 Prese ntation Outline 1. Official Indians: Identity per Blood Quantum 2. Historical Indians: Charging Elk in Europe 3. Experienced Indians: Reservation U.S.A. Conclusions Quotations 2. Historical Indians James Welch, The Heartsong of Charging Elk (2000): He liked this wide street with the rows of knobby trees on the street-side edge of the broad walkway. There were many places where he could look in windows at clothes and sweets and knives and everything a man might want. There were cafés, but he hadn’t the courage yet to enter one for a small cup of the bitter pejuta sapa. But he always stopped at a particular kiosk with a bright green-and- white-striped awning that sold the flimsy papers with wasichu writing on them. Often they had pictures on them, drawings, mostly of men he thought all looked alike, with their beards and stiff collars. (165) [after being shouted at in a restaurant, ] Charging Elk sat for a moment, looking down at his half-eaten meal, confused. He understood why the wasicun miners in Paha Sapa hated him, but why would these sailors hate him in Marseille? There were many people of many colors here. Why would they choose him? He had spent the past three winters making himself invisible, yet they knew him right away. -

American Book Awards 2004

BEFORE COLUMBUS FOUNDATION PRESENTS THE AMERICAN BOOK AWARDS 2004 America was intended to be a place where freedom from discrimination was the means by which equality was achieved. Today, American culture THE is the most diverse ever on the face of this earth. Recognizing literary excel- lence demands a panoramic perspective. A narrow view strictly to the mainstream ignores all the tributaries that feed it. American literature is AMERICAN not one tradition but all traditions. From those who have been here for thousands of years to the most recent immigrants, we are all contributing to American culture. We are all being translated into a new language. BOOK Everyone should know by now that Columbus did not “discover” America. Rather, we are all still discovering America—and we must continue to do AWARDS so. The Before Columbus Foundation was founded in 1976 as a nonprofit educational and service organization dedicated to the promotion and dissemination of contemporary American multicultural literature. The goals of BCF are to provide recognition and a wider audience for the wealth of cultural and ethnic diversity that constitutes American writing. BCF has always employed the term “multicultural” not as a description of an aspect of American literature, but as a definition of all American litera- ture. BCF believes that the ingredients of America’s so-called “melting pot” are not only distinct, but integral to the unique constitution of American Culture—the whole comprises the parts. In 1978, the Board of Directors of BCF (authors, editors, and publishers representing the multicultural diversity of American Literature) decided that one of its programs should be a book award that would, for the first time, respect and honor excellence in American literature without restric- tion or bias with regard to race, sex, creed, cultural origin, size of press or ad budget, or even genre. -

York University Graduate Program in English Post-1900 US Literature Comprehensive Reading List Prose

York University Graduate Program in English Post-1900 US Literature Comprehensive Reading List [Updated MarCh 2007] Candidates should submit a reading list composed of the following texts. Where indicated, students may substitute another appropriate text by the same author. Additionally, up to 10% of each section of this list may be replaced with alternatives decided upon by the candidate in consultation with the examination supervisor. Note well: In addition to mastering the list provided below, candidates in twentieth-century American literature are expected to develop a familiarity with a range of major American literary texts from before the 20th century. Ideally, candidates planning to specialize as Americanists will sit the pre-1900 American Literature exam and the twentieth-century American Literature exam. Candidates who opt not to take the earlier American exam should refer to that exam’s reading list in consultation with their supervisor to determine which American authors/texts from before 1900 are unavoidable prerequisites for this field exam. Likely possibilities include: Mark Twain, Herman Melville, Harriet Beecher Stowe, Emily Dickinson, Walt Whitman, Ralph Waldo Emerson, etc. Candidates will not be examined on these materials as part of this field, but exam questions may take for granted knowledge of such fundamental texts. If this will be a second field exam, students are required to submit a copy of their first field examination reading list along with the final copy of the 20th century American list. Prose Candidates should read texts by approximately 10-15 authors from each time period below, selected in consultation with their supervisors. A total of approximately 45-55 prose texts by as many authors is appropriate. -

Northportcollectbib2012.Pdf (593.1Kb)

Northport Native American Special Emphasis Collection Stony Brook University Stony Brook, N.Y. Compiled by Karen D’Angelo Library Technical Services Stony Brook University 2012 All of the materials included in this bibliography provide valuable educational opportunities to learn more about First Nations Peoples. The Northport Native American Special Emphasis Collection has been relocated to the Frank Melville Jr. Memorial Library at Stony Brook University. The bibliography can be viewed at the Stony Brook web page: https://dspace.sunyconnect.suny.edu/handle/1951/42805 You can ask your local public library if they have copies of the materials. In addition to the Northport Native American Special Emphasis Collection other materials on Native American history and culture can be found at the Frank Melville Jr. Memorial Library. You can search the STARS catalog http://www.stonybrook.edu/~library/index.html or ask a librarian for assistance. The Stony Brook main library can be contacted at: (631) 632-7100. 2nd annual Native American Indian Ceremony. – November 7, 2001. VHS **Contact the Cataloging Department – 631-632-7137** 2nd annual Native American Ceremony. – November 7, 2001. VHS **Contact the Cataloging Department – 631-632-7137** 2nd annual video conference VHA Bronx : emerging issues in SW and aging “differences do make a difference” – June 5, 2002. VHS **Contact the Cataloging Department – 631-632-7137** 3rd annual Native American ceremony. – Novermber 6, 2002. VHS – 60 min. **Contact the Cataloging Department – 631-632-7137** 7th annual VAMC Northport Native American heritage IEEO program with Josephine Smith of Shinnecock Nation : speaking on traditional medicine. DVD **Contact the Cataloging Department – 631-632-7137* 8th annual VAMC tribute to Native American Indian employees and veterans “American Indian Cultural Practices in Healing. -

James Welch's Winter in the Blood: Thawing the Fragments of Misconception in Native American Fiction Mario A

Eastern Illinois University The Keep Masters Theses Student Theses & Publications 1996 James Welch's Winter in the Blood: Thawing the Fragments of Misconception in Native American Fiction Mario A. Leto II Eastern Illinois University This research is a product of the graduate program in English at Eastern Illinois University. Find out more about the program. Recommended Citation Leto, Mario A. II, "James Welch's Winter in the Blood: Thawing the Fragments of Misconception in Native American Fiction" (1996). Masters Theses. 1903. https://thekeep.eiu.edu/theses/1903 This is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Theses & Publications at The Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of The Keep. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THESIS REPRODUCTION CERTIFICATE TO: Graduate Degree Candidates (who have written formal theses) SUBJECT: Permission to Reproduce Theses The University Library is rece1v1ng a number of requests from other institutions asking permission to reproduce dissertations for inclusion in their library holdings. Although no copyright laws are involved, we feel that professional courtesy demands that permission be obtained from the author before we allow theses to be copied. PLEASE SIGN ONE OF THE FOLLOWING STATEMENTS: Booth Library of Eastern Illinois University has my permission to lend my thesis to a reputable college or university for the purpose of copying it for inclusion in that institution's library or research holdings. ~rJate I respectfully request Booth Library of Eastern Illinois University not allow my thesis to be reproduced because: Author Date James Welch's Winter in the Blood: Thawing the Fragments of Misconception in Native American Fiction (TITLE) BY Mario A. -

Rehtinking Resistance: Race, Gender, and Place in the Fictive and Real Geographies of the American West

REHTINKING RESISTANCE: RACE, GENDER, AND PLACE IN THE FICTIVE AND REAL GEOGRAPHIES OF THE AMERICAN WEST by TRACEY DANIELS LERBERG DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at The University of Texas at Arlington May 2016 Arlington, Texas Supervising Committee: Stacy Alaimo, Supervising Professor Neill Matheson Christopher Morris Kenneth Roemer Cedrick May, Texas Christian University Abstract Rethinking Resistance: Race, Gender, and Place in the Fictive and Real Geographies of the American West by Tracey Daniels Lerberg, Ph.D. The University of Texas at Arlington, 2016 Supervising Professor: Stacy Alaimo This project traces the history of the American West and its inhabitants through its literary, cinematic and cultural landscape, exploring the importance of public and private narratives of resistance, in their many iterations, to the perceived singular trajectory of white masculine progress in the American west. The project takes up the calls by feminist and minority scholars to broaden the literary history of the American West and to unsettle the narrative of conquest that has been taken up to enact a particular kind of imaginary perversely sustained across time and place. That the western heroic vision resonates today is perhaps no significant revelation; however, what is surprising is that their forward echoes pulsate in myriad directions, cascading over the stories of alternative voices, that seem always on the verge of slipping away from our collective memories, of ii being conquered again and again, of vanishing. But a considerable amount of recovery work in the past few decades has been aimed at revising the ritualized absences in the North American West to show that women, Native Americans, African Americans, Mexican Americans and other others were never absent from this particular (his)story.