Chapter 7 Assessment of Stormwater Best Management Practice

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Urban Flooding Mitigation Techniques: a Systematic Review and Future Studies

water Review Urban Flooding Mitigation Techniques: A Systematic Review and Future Studies Yinghong Qin 1,2 1 College of Civil Engineering and Architecture, Guilin University of Technology, Guilin 541004, China; [email protected]; Tel.: +86-0771-323-2464 2 College of Civil Engineering and Architecture, Guangxi University, 100 University Road, Nanning 530004, China Received: 20 November 2020; Accepted: 14 December 2020; Published: 20 December 2020 Abstract: Urbanization has replaced natural permeable surfaces with roofs, roads, and other sealed surfaces, which convert rainfall into runoff that finally is carried away by the local sewage system. High intensity rainfall can cause flooding when the city sewer system fails to carry the amounts of runoff offsite. Although projects, such as low-impact development and water-sensitive urban design, have been proposed to retain, detain, infiltrate, harvest, evaporate, transpire, or re-use rainwater on-site, urban flooding is still a serious, unresolved problem. This review sequentially discusses runoff reduction facilities installed above the ground, at the ground surface, and underground. Mainstream techniques include green roofs, non-vegetated roofs, permeable pavements, water-retaining pavements, infiltration trenches, trees, rainwater harvest, rain garden, vegetated filter strip, swale, and soakaways. While these techniques function differently, they share a common characteristic; that is, they can effectively reduce runoff for small rainfalls but lead to overflow in the case of heavy rainfalls. In addition, most of these techniques require sizable land areas for construction. The end of this review highlights the necessity of developing novel, discharge-controllable facilities that can attenuate the peak flow of urban runoff by extending the duration of the runoff discharge. -

Highlights from WERF Stormwater Research and Future Opportunities

Highlights from WERF Stormwater Research and Future Opportunities Jeff Moeller, P.E. Director of Water Technologies Water Environment Research Foundation [email protected] WEFTEC 2013 Stormwater Pavilion BMPs & Green Infrastructure "We still do not know one thousandth of one percent of what nature has revealed to us." - Albert Einstein What data is available on the performance of green infrastructure and BMPs? BMP Database Overview BMP Database includes over 530 BMP monitoring studies, including significant GI/LID BMPs From 2008-2013, a key focus has been to better integrate green infrastructure through: Monitoring Guidance (Updated) New Data Entry Spreadsheets Updated Analysis Results BMP Category Count BR Bioretention 31 BMP Summary BI Biofilter - Grass Strip 45 BS Biofilter-Grass Swale 41 Representative Green CO Composite 25 Infrastructure BMP Categories: DB Detention Basin 39 GR Green Roof 17 Bioretention IB Infiltration Basin 2 LD LID 2 Biofilters MD Manufactured Device 82 MF Media Filter 38 Green Roofs MP Maintenance Practice 28 Permeable Pavement OT Other 6 PP Porous Pavement 39 Rainwater Harvesting PT Percolation Trench 13 RP Retention Pond 75 Site-scale LID WB Wetland Basin 31 WC Wetland Channel 19 Total BMPs 533 CX Control/Ref. Sites 21 Quick Overview of 2012-13 Performance Summaries Updates: TSS, Nutrients, Metals, Bacteria, Volume Reduction New Detailed Analyses: Bioretention Volume Reduction Manufactured Device Unit Processes New On-line Tools: Map Interface Custom Statistical Queries On-line Search Tool BMP Database Vision International Stormwater BMP Database Urban Stormwater Construction Stormwater Agricultural BMPs BMPs Quality BMPs Partners: Partners: Partners: Partners: WERF University of Alabama IECA WERF NCGA EPA ASCE-EWRI MCGA FHWA Planned for 2013. -

King County Drainage Maintenance Standards for Commercial and Multifamily Drainage Facilities

KING COUNTY DRAINAGE MAINTENANCE STANDARDS FOR COMMERCIAL AND MULTIFAMILY DRAINAGE FACILITIES Definitions, Defects & Maintenance Necessary to Bring to Standard June 2008 Contents A. Type I Catch Basin ............................................................................................................... 4 B. Type II Catch Basin ............................................................................................................. 5 C. Flow Restrictor .................................................................................................................... 7 D. Debris Barrier ..................................................................................................................... 8 E. Energy Dissipater/Dispersion Trench .................................................................................... 9 F. Pipe/Culvert ......................................................................................................................10 G. Ditch .................................................................................................................................10 H. Fencing .............................................................................................................................. 11 I. Access Road .......................................................................................................................13 J. Other—Specific to Ponds (Including Infiltration Ponds) ........................................................14 K. Other—Specific to Tanks (Including -

Infiltration/Percolation Trench

97 ACTIVITY: Infiltration / Percolation Trench I – 01 Targeted Constituents z Significant Benefit Partial Benefit { Low or Unknown Benefit z Sediment Heavy Metals Floatable Materials Oxygen Demanding Substances Nutrients Toxic Materials Oil & Grease { Bacteria & Viruses { Construction Wastes Implementation Requirements z High Medium { Low Capital Costs O & M Costs Maintenance { Training Description This BMP includes the infiltration / percolation trench, in which stormwater runoff is infiltrated into a shallow, excavated trench backfilled with stone aggregate rather than discharged to a surface channel. It is located below ground or at-grade and is usually designed to accept the first flush of stormwater runoff, temporarily store it, and eventually allow it to infiltrate into the subsoil through its sides and bottom. Infiltration rates in many areas of the state are typically poor due to clay soils and bedrock. Such locations may not be suitable of infiltration trench BMPs. Infiltration systems work best at sites having sandy loam types of soils. Areas containing karst topography and sinkholes may initially appear to have excellent infiltration, but should be considered as unreliable and will require very careful investigation and analysis. Selection Following are some criteria for placement of infiltration trenches: Criteria Infiltration trenches may be used for stormwater quality and stormwater detention at small project sites only if soil, geologic and groundwater conditions are suitable. Soils must have adequate infiltration rates as measured or tested in the field. No unfavorable geologic conditions shall be present that would indicate sinkholes or underground passageways. Infiltration trenches are often used in low to medium density, residential and commercial areas with limited and costly land space. -

Urban Stormwater BMP Performance Monitoring a Guidance Manual for Meeting the National Stormwater BMP Database Requirements April 25, 2002 45

3 Developing a BMP Monitoring Program This chapter describes the steps involved in developing and implementing a monitoring program to evaluate BMP effectiveness. Regardless of the scope and objectives, designing a monitoring plan generally involves four phases: Phase 1: Determine the objectives and scope of your monitoring program Phase 2: Develop the monitoring plan in view of your objectives Phase 3: Implement the monitoring plan Phase 4: Evaluate and report the results of monitoring The activities associated with each phase are listed below. Phase 1: Determine Objectives and Scope · Identify permit requirements and/or information needs · Compile and review existing information (maps, drawings, results from prior sampling, etc.) relevant to permit requirements and/or information needs · Develop monitoring program objectives and scope Phase 2: Develop Monitoring Plan · Select monitoring locations · Select monitoring frequency · Select parameters and analytical methods · Select monitoring methods and equipment · Select storm criteria (i.e., size, duration, season) · Develop mobilization procedures · Prepare a quality assurance/quality control plan · Prepare a health and safety plan · Prepare a data management plan Phase 3: Implement Monitoring Plan · Install equipment (and modify channels, if applicable) · Test and calibrate equipment · Conduct training · Conduct monitoring (collect samples) · Conduct analyses (field and/or laboratory) Urban Stormwater BMP Performance Monitoring A Guidance Manual for Meeting the National Stormwater BMP Database Requirements April 25, 2002 45 Phase 4: Evaluate and Report Results · Validate chemical data quality · Evaluate results · Report the results Several of the steps in developing a monitoring program are dependent on one another. Consequently, earlier steps may need to be revisited and refined throughout the planning process. -

Amend PFM 6-0000 (STORM DRAINAGE – TABLE of CONTENTS) to Read As Follows

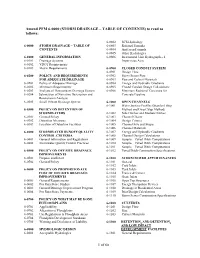

Amend PFM 6-0000 (STORM DRAINAGE – TABLE OF CONTENTS) to read as follows: 6-0802 SCS Hydrology 6-0000 STORM DRAINAGE – TABLE OF 6-0803 Rational Formula CONTENTS 6-0804 Anderson Formula 6-0805 Other Hydrologies 6-0100 GENERAL INFORMATION 6-0806 Incremental Unit Hydrograph – 1 6-0101 Drainage Systems Impervious Acre 6-0102 VDOT Requirements 6-0103 Metric Requirements 6-0900 CLOSED CONDUIT SYSTEM 6-0901 Design Flow 6-0200 POLICY AND REQUIREMENTS 6-0902 Storm Sewer Pipe FOR ADEQUATE DRAINAGE 6-0903 Pipe and Culvert Materials 6-0201 Policy of Adequate Drainage 6-0904 Energy and Hydraulic Gradients 6-0202 Minimum Requirements 6-0905 Closed Conduit Design Calculations 6-0203 Analysis of Downstream Drainage System 6-0906 Minimum Radius of Curvature for 6-0204 Submission of Narrative Description and Concrete Pipeline Downstream Analysis 6-0205 Small Private Drainage System 6-1000 OPEN CHANNELS 6-1001 Water Surface Profiles (Standard Step 6-0300 POLICY ON DETENTION OF Method and Direct Step Method) STORMWATERS 6-1002 Side Ditches and Median Ditches 6-0301 General Policy 6-1003 Channel Charts 6-0302 Detention Measures 6-1004 Design Criteria 6-0303 Location of Detention Facilities 6-1005 Channel Size and Shape 6-1006 Channel Materials 6-0400 STORMWATER RUNOFF QUALITY 6-1007 Energy and Hydraulic Gradients CONTROL CRITERIA 6-1008 Channel Design Calculations 6-0401 General Information and Regulations 6-1009 Sample – Paved Ditch Computations 6-0402 Stormwater Quality Control Practices 6-1010 Sample – Paved Ditch Computations 6-1011 Sample – Paved Ditch -

6-0000 STORM DRAINAGE 2001 PFM Page

6-0000 STORM DRAINAGE 6-0000 STORM DRAINAGE – TABLE OF 6-0802 NRCS (formerly SCS) Hydrology CONTENTS 6-0803 Rational Formula 6-0804 Anderson Formula 6-0100 GENERAL INFORMATION 6-0805 Other Hydrologies 6-0101 Drainage Systems 6-0806 Incremental Unit Hydrograph – 1 Imper- 6-0102 VDOT Requirements vious Acre 6-0103 Metric Requirements 6-0200 POLICY AND REQUIREMENTS 6-0900 CLOSED CONDUIT SYSTEM FOR ADEQUATE DRAINAGE 6-0201 Policy of Adequate Drainage 6-0901 Design Flow 6-0202 Minimum Requirements 6-0902 Storm Sewer Pipe 6-0203 Analysis of Downstream Drainage 6-0903 Pipe and Culvert Materials System 6-0904 Energy and Hydraulic Gradients 6-0204 Submission of Narrative Description and 6-0905 Closed Conduit Design Calculations Downstream Analysis 6-0906 Minimum Radius of Curvature for Con- 6-0205 Small Private Drainage System crete Pipeline 6-0300 POLICY ON DETENTION OF 6-1000 OPEN CHANNELS STORMWATERS 6-1001 Water Surface Profiles (Standard Step 6-0301 General Policy Method and Direct Step Method) 6-0302 Detention Measures 6-1002 Side Ditches and Median Ditches 6-0303 Location of Detention Facilities 6-1003 Channel Charts 6-1004 Design Criteria 6-0400 STORMWATER RUNOFF QUALITY 6-1005 Channel Size and Shape CONTROL CRITERIA 6-1006 Channel Materials 6-0401 General Information and Regulations 6-1007 Energy and Hydraulic Gradients 6-0402 Stormwater Quality Control Practices 6-1008 Channel Design Calculations 6-1009 Sample – Paved Ditch Computations 6-0500 POLICY ON OFF-SITE DRAINAGE 6-1010 Sample – Paved Ditch Computations IMPROVEMENTS 6-1011 Sample -

Decentralized BMP Categories Chart

CITY OF ARROYO GRANDE COMMUNITY DEVELOPMENT DEPARTMENT Decentralized Stormwater Structural Best Management Practices Decentralized Stormwater Structural Best Management Practices (BMP) Description: System is small to moderate in size and accepts runoff from a single land use drainage area less than 10.0 acres. Structural BMPType Description Vegetated BMP that filters stormwater through a specialized soil media and discharges via an underdrain. Little to no overflow of captured runoff volume. Biofiltration Outlet design requires surface ponding prior to surface outflow typically with a maximum ponding depth of 6 inches. (Examples: Lined rain Site designs use soil media ideally 18-24 inches in depth to enhance garden.) filtration processes to retain pollutants. Treatment Process: Bio-Chemical Cycling, Particle Capture Vegetation: Yes Location: Above Ground Type: Decentralized Vegetated retention structure where the base of the BMP is not lined and allows for infiltration to unsaturated zone. Designs may or may not include an underdrain to discharge some fraction of treated water. Design will include either passive surface outlet or piped overflow to Bioretention allow retention and ponding. Design will include soil media ideally 18-24 inches in depth to enhance (Examples: Rain garden with filtration processes to retain pollutants. infiltration) May include aggregate subsurface layer to enhance storage or infiltration. Vegetation types must be able to tolerate stormwater ponding and drought conditions. Treatment Process: Bio-Chemical -

6-0000 Storm Drainage for Grandfathered & Time Limited

6-0000 STORM DRAINAGE TABLE OF CONTENTS 6-0100 GENERAL INFORMATION See current PFM ..................................................................................... 5 6-0200 POLICY AND REQUIREMENTS FOR ADEQUATE DRAINAGE ................................................ 5 6-0201 Policy of Adequate Drainage See current PFM .......................................................................................... 5 6-0202 Minimum Requirements See current PFM ................................................................................................. 5 6-0203 Analysis of Downstream Drainage System .................................................................................................. 5 6-0204 Submission of Narrative Description and Downstream Analysis ............................................................... 9 6-0205 Small Private Drainage System See current PFM .................................................................................... 10 6-0300 POLICY ON DETENTION OF STORMWATERS ........................................................................... 11 6-0301 General Policy ............................................................................................................................................... 11 6-0302 Detention Measures ...................................................................................................................................... 11 6-0303 Location of Detention Facilities ................................................................................................................. -

On the Design of Percolation Facilities Communication of the Department of Sanitary Engineering and VI/C'ltflr Management May 1996 Fr

c:>soo ISSN 0169-6246 On the Design of Percolation Facilities Communication of the Department of Sanitary Engineering and VI/C'ltflr Management May 1996 fr. N.J. Monster I ir. M.J. Leeflang Ni Faculty of Civil Engineering and Geosciences Department of Water Management, Environmental and Sanitary Engineering TU Delft Land- and Water Management Section Delft University of Technology On the Design of Percolation Facilities Communication nr.: 66 M.J. Leetlang N.J. Monster Delft University of Technology May 1996 Faculty of Civil Engineering Department of Water Management, Environmental and Sanitary Engineering Contents Contents Contents Summary Samenvatting V 1. Introduction 2. Applicable disconnection methods and their design 2.1 Introduction 3 2.2 EvaluatiOn of the various disconnection methods 3 2.3 Evaluatton of the design procedures 3 2.4 Shortcomings and proposed improvements for the design procedure 5 2.5 Proposed disconnection methods 5 3. A design graph based on simulations 3.1 Introduction 7 3.2 The traditional Storage-Design Discharge-Frequency curve 7 3.3 Development of the new des1gn graph 10 4. The modelling of the percolation trench, calculations and results 4. 1 Introduction 13 4.2 The reservoir model 13 4.3 Four different scenarios for the percolation rate from the reservoir 15 4.4 Simulations with the four scenarios 1 7 4.5 S1mulations with other scenarios 19 4.6 A percolatiOn trench with a drain on the bottom 20 5. Design graphs percolation trench 23 6. The Mulden-Rigole system 6.1 Introduction 33 6.2 The model 33 6.3 The optimal use of the system 34 6.4 The design graphs of the Mulden-Rigole system 35 7. -

Wastewater Treatment

Laois County Council Date: 24/09/2019 c/ o Darragh Carey Beng Bsc (Hons) MIEI AOCA , Lismard House, Timahoe Road, Portlaois, Co. Laois. Tel: 057 86 63244 & Email: [email protected] Site Suitability Report for Planning permission for dwelling and proprietary treatment system at: Coolroe, Ballybrittas, Co. Laois. The Proposed System: Molloy Environmental Wastewater Secondary Treatment System (4 – 8 P.E.) The proposed Wastewater Treatment System is EN 12566-3 certified by PIA & Molloy Klaro, is an SBR (Sequencing Batch Reactor) mechanical aeration system designed to cater for 4 – 8 P.E. (population equivalent ), for Klaro aerated Technology for SBRs. The secondary treatment system is inclusive, amongst others, of: Dual chambered pre-cast concrete tank for primary treatment (Primary tank). A single chamber pre-cast concrete tank for secondary treatment [Sequential Batch Reactor (SBR)] tank, (Ref: EPA, CoP, 2009, Fig 9.3, page 39). Delivery, installation and commissioning by employees of MOLLOY ENVIRONMENTAL. The Molloy Environmental Effluent Treatment System is fitted with a comprehensive PLC controller and alarm system. Alarming will occur with overloading or under-loading of the system and if there is a failure/ blockage of the pumps or aerator device. In addition, the system has a high water alarm system. The system uses an economy mode for energy conservation when inputs are low. The primary, buffer and treatment tank is installed underground and will not give rise to any noticeable noise nuisance or any unpleasant odours once the system is correctly vented and maintained. The system will be commissioned by Molloy Precast Products trained technicians. A certificate of conformance will be issued by the commissioning technician, on the condition that the treatment system has been correctly installed and the relevant civil works have been correctly carried out. -

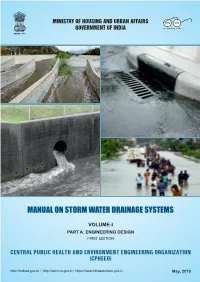

Storm Water Drainage Systems Volume I Engineering Size

Table of Contents CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................. 14 1.1 General .................................................................................................................................... 14 1.2 Status of Urban Drainage System in India ......................................................................... 14 1.3 Causes of urban flooding ...................................................................................................... 15 1.4 Need for Storm Water Drainage Manual ............................................................................ 16 1.5 Scope of Manual ..................................................................................................................... 17 1.6 Use of Manual ......................................................................................................................... 18 CHAPTER 2: PROJECT PLANNING AND INVESTIGATION .............................................. 19 2.1 General .................................................................................................................................... 19 2.2 Objectives of Planning & Investigation ................................................................................ 19 2.3 Data Collection, Survey and Investigation ......................................................................... 20 2.3.1 Data Collection ..............................................................................................................