Twitter, Social Support Messages and the #Metoo Movement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Social Media Tool Analysis

Social Media Tool Analysis John Saxon TCO 691 10 JUNE 2013 1. Orkut Introduction Orkut is a social networking website that allows a user to maintain existing relationships, while also providing a platform to form new relationships. The site is open to anyone over the age of 13, with no obvious bent toward one group, but is primarily used in Brazil and India, and dominated by the 18-25 demographic. Users can set up a profile, add friends, post status updates, share pictures and video, and comment on their friend’s profiles in “scraps.” Seven Building Blocks • Identity – Users of Orkut start by establishing a user profile, which is used to identify themselves to other users. • Conversations – Orkut users can start conversations with each other in a number of way, including an integrated instant messaging functionality and through “scraps,” which allows users to post on each other’s “scrapbooks” – pages tied to the user profile. • Sharing – Users can share pictures, videos, and status updates with other users, who can share feedback through commenting and/or “liking” a user’s post. • Presence – Presence on Orkut is limited to time-stamping of posts, providing other users an idea of how frequently a user is posting. • Relationships – Orkut’s main emphasis is on relationships, allowing users to friend each other as well as providing a number of methods for communication between users. • Reputation – Reputation on Orkut is limited to tracking the number of friends a user has, providing other users an idea of how connected that user is. • Groups – Users of Orkut can form “communities” where they can discuss and comment on shared interests with other users. -

Los Angeles Lawyer June 2010 June2010 Issuemaster.Qxp 5/13/10 12:26 PM Page 5

June2010_IssueMaster.qxp 5/13/10 12:25 PM Page c1 2010 Lawyer-to-Lawyer Referral Guide June 2010 /$4 EARN MCLE CREDIT PLUS Protecting Divorce Web Site Look and Estate and Feel Planning page 40 page 34 Limitations of Privacy Rights page 12 Revoking Family Trusts page 16 The Lilly Ledbetter Fair Pay Act Strength of page 21 Character Los Angeles lawyers Michael D. Schwartz and Phillip R. Maltin explain the effective use of character evidence in civil trials page 26 June2010_IssueMaster.qxp 5/13/10 12:42 PM Page c2 Every Legal Issue. One Legal Source. June2010_IssueMaster.qxp 5/13/10 12:25 PM Page 1 Interim Dean Scott Howe and former Dean John Eastman at the Top 100 celebration. CHAPMAN UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF LAW PROUDLY ANNOUNCES OUR RANKING AMONG THE TOP 100 OF ONE UNIVERSITY DRIVE, ORANGE, CA 92866 www.chapman.edu/law June2010_IssueMaster.qxp 5/13/10 12:25 PM Page 2 0/&'*3. ."/:40-65*0/4 Foepstfe!Qspufdujpo Q -"8'*3.$-*&/54 Q"$$&445007&3130'&44*0/"- -*"#*-*5:1307*%&34 Q0/-*/&"11-*$"5*0/4'03 &"4:$0.1-&5*0/ &/%034&%130'&44*0/"--*"#*-*5:*/463"/$,&3 Call 1-800-282-9786 today to speak to a specialist. 5 ' -*$&/4&$ 4"/%*&(003"/(&$06/5:-04"/(&-&44"/'3"/$*4$0 888")&3/*/463"/$&$0. June2010_IssueMaster.qxp 5/13/10 12:26 PM Page 3 FEATURES 26 Strength of Character BY MICHAEL D. SCHWARTZ AND PHILLIP R. MALTIN Stringent rules for the admission of character evidence in civil trials are designed to prevent jurors from deciding a case on the basis of which party is more likeable 34 Parting of the Ways BY HOWARD S. -

Seamless Interoperability and Data Portability in the Social Web for Facilitating an Open and Heterogeneous Online Social Network Federation

Seamless Interoperability and Data Portability in the Social Web for Facilitating an Open and Heterogeneous Online Social Network Federation vorgelegt von Dipl.-Inform. Sebastian Jürg Göndör geb. in Duisburg von der Fakultät IV – Elektrotechnik und Informatik der Technischen Universität Berlin zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades Doktor der Ingenieurwissenschaften - Dr.-Ing. - genehmigte Dissertation Promotionsausschuss: Vorsitzender: Prof. Dr. Thomas Magedanz Gutachter: Prof. Dr. Axel Küpper Gutachter: Prof. Dr. Ulrik Schroeder Gutachter: Prof. Dr. Maurizio Marchese Tag der wissenschaftlichen Aussprache: 6. Juni 2018 Berlin 2018 iii A Bill of Rights for Users of the Social Web Authored by Joseph Smarr, Marc Canter, Robert Scoble, and Michael Arrington1 September 4, 2007 Preamble: There are already many who support the ideas laid out in this Bill of Rights, but we are actively seeking to grow the roster of those publicly backing the principles and approaches it outlines. That said, this Bill of Rights is not a document “carved in stone” (or written on paper). It is a blog post, and it is intended to spur conversation and debate, which will naturally lead to tweaks of the language. So, let’s get the dialogue going and get as many of the major stakeholders on board as we can! A Bill of Rights for Users of the Social Web We publicly assert that all users of the social web are entitled to certain fundamental rights, specifically: Ownership of their own personal information, including: • their own profile data • the list of people they are connected to • the activity stream of content they create; • Control of whether and how such personal information is shared with others; and • Freedom to grant persistent access to their personal information to trusted external sites. -

Confronting Antisemitism in Modern Media, the Legal and Political Worlds an End to Antisemitism!

Confronting Antisemitism in Modern Media, the Legal and Political Worlds An End to Antisemitism! Edited by Armin Lange, Kerstin Mayerhofer, Dina Porat, and Lawrence H. Schiffman Volume 5 Confronting Antisemitism in Modern Media, the Legal and Political Worlds Edited by Armin Lange, Kerstin Mayerhofer, Dina Porat, and Lawrence H. Schiffman ISBN 978-3-11-058243-7 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-067196-4 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-067203-9 DOI https://10.1515/9783110671964 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. For details go to https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Library of Congress Control Number: 2021931477 Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. © 2021 Armin Lange, Kerstin Mayerhofer, Dina Porat, Lawrence H. Schiffman, published by Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston The book is published with open access at www.degruyter.com Cover image: Illustration by Tayler Culligan (https://dribbble.com/taylerculligan). With friendly permission of Chicago Booth Review. Printing and binding: CPI books GmbH, Leck www.degruyter.com TableofContents Preface and Acknowledgements IX LisaJacobs, Armin Lange, and Kerstin Mayerhofer Confronting Antisemitism in Modern Media, the Legal and Political Worlds: Introduction 1 Confronting Antisemitism through Critical Reflection/Approaches -

Metoo: Why Twitter Doesn't Do Enough

Chapman University Chapman University Digital Commons Student Scholar Symposium Abstracts and Posters Center for Undergraduate Excellence Fall 12-2-2020 #MeToo: Why Twitter Doesn't Do Enough Tara Mann [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.chapman.edu/cusrd_abstracts Part of the Gender and Sexuality Commons, Race and Ethnicity Commons, Rhetoric Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Mann, Tara, "#MeToo: Why Twitter Doesn't Do Enough" (2020). Student Scholar Symposium Abstracts and Posters. 408. https://digitalcommons.chapman.edu/cusrd_abstracts/408 This Poster is brought to you for free and open access by the Center for Undergraduate Excellence at Chapman University Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Student Scholar Symposium Abstracts and Posters by an authorized administrator of Chapman University Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. #MeToo: Why Twitter Doesn’t Do Enough Tara Mann ENG 446 Feminist Rhetorics, Professor Ian Barnard Chapman University Department of English How #MeToo Began Conclusion In 2017 Alyssa Milano tweeted the hashtag Even with all of the attention given to #MeToo to give a voice to victims and survivors Me Too, things have not improved as of sexual harassment after accusations were much as they need to. Despite the made against Hollywood producer Harvey truth available to everyone about how Weinstein. Share the Load (mrschachter). “We have to stop saying the #metoo movement deep the issue is and what happens started in 2017. Saying that IS Black femme erasure.” Oct 2, 2020, 10:17 am. Tweet. to the perpetrators versus the victims, Milano’s involvement—involvement by a privileged there is still the fear of retaliation if white woman—made the Me Too movement what it is you speak up. -

Dissertation Online Consumer Engagement

DISSERTATION ONLINE CONSUMER ENGAGEMENT: UNDERSTANDING THE ANTECEDENTS AND OUTCOMES Submitted by Amy Renee Reitz Department of Journalism and Technical Communication In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Colorado State University Fort Collins, Colorado Summer 2012 Doctoral Committee: Advisor: Jamie Switzer Co-Advisor: Ruoh-Nan Yan Jennifer Ogle Donna Rouner Peter Seel Copyright by Amy Renee Reitz 2012 All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT ONLINE CONSUMER ENGAGEMENT: UNDERSTANDING THE ANTECEDENTS AND OUTCOMES Given the adoption rates of social media and specifically social networking sites among consumers and companies alike, practitioners and academics need to understand the role of social media within a company’s marketing efforts. Specifically, understanding the consumer behavior process of how consumers perceive features on a company’s social media page and how these features may lead to loyalty and ultimately consumers’ repurchase intentions is critical to justify marketing efforts to upper management. This study focused on this process by situating online consumer engagement between consumers’ perceptions about features on a company’s social media page and loyalty and (re)purchase intent. Because online consumer engagement is an emerging construct within the marketing literature, the purpose of this study was not only to test the framework of online consumer engagement but also to explore the concept of online consumer engagement within a marketing context. The study refined the definition of online -

Can Women Break the Glass Ceiling?: an Analysis of #Metoo Hashtagged Posts on Twitter

Can Women Break the Glass Ceiling?: An Analysis of #MeToo Hashtagged Posts on Twitter Naeemul Hassan Manash Kumar Mandal Mansurul Bhuiyan University of Mississippi Khulna University of Engineering and IBM Research, Almaden nhassan@olemiss:edu Technology mansurul:bhuiyan@ibm:com manashmndl@gmail:com Aparna Moitra Syed Ishtiaque Ahmed University of Delhi University of Toronto aparna:moitra@gmail:com ishtiaque@cs:toronto:edu ABSTRACT social activist Tarana Burke launched a grass-root level campaign In October 2017, there happened the uprising of an unprecedented for “empowering through empathy" for the women of color within 3 online movement on social media by women across the world who their community . Milano’s call for sharing harassment experiences started publicly sharing their untold stories of being sexually ha- with #MeToo hashtag that followed her own allegation against rassed along with the hashtag #MeToo (or some variants of it). Harvey Weinstein, an American film producer, for sexually abusing 4 Those stories did not only strike the silence that had long hid the her took the original movement to a whole new level and millions perpetrators, but also allowed women to discharge some of their of women around the world started participating. Before this, a 5 bottled-up grievances, and revealed many important information few other hashtags were also used for similar purposes , including surrounding sexual harassment. In this paper, we present our anal- #MyHarveyWeinstein, #YouOkSis, #WhatWereYouWearing, and ysis of about one million such tweets collected between October #SurvivorPrivilege. However none of them could create such a 15 and October 31, 2017 that reveals some interesting patterns and massive movement on social media. -

Magazine of the Max Planck Phd

m et agazine of the max planck phd n Publisher: Max Planck PhDnet (2008) Editorial board: Verena Conrad, MPI for Biological Cybermetics, Tübingen Corinna Handschuh, MPI for Evolutionary Anthroplology, Leipzig Julia Steinbach, MPI for Biogeochemistry, Jena Peter Buschkamp, MPI for Extraterrestrial Physics, Garching Franziska Hartung, MPI for Experimental Biology, Göttingen Design: offspring Silvana Schott, MPI for Biogeochemistry, Jena Table of Contents Dear reader, you have the third issue of the Offspring So, here you see the first issue of this new Dear Reader 3 in your hands, the official magazine of Offspring and we hope you enjoy reading the Max Planck PhDnet. This magazine it! The main topic of this issue is “Success”, A look back ... 4 was started in 2005 to communicate the for instance you may read interviews with ... and forward 5 network‘s activities and to provide rele- MPI-scientists at different levels of their Introduction of the new Steering Group 6 vant information to PhD students at all career, giving their personal perception of institutes. Therefore, the first issues mainly scientific success, telling how they celeb- Success story 8 contained reports about previous meetings rate success and how they cope with fai- Questionnaire on Scientific Success 10 and announcements of future events. lure; you will learn how two foreign PhD What the ?&%@# is Bologna? 14 students succeeded in getting along in However, at the PhD representatives’ mee- Germany in their first months – and of ting in Leipzig, November 2006, a new Workgroups of the PhDnet 15 course about the successful work of the work group was formed as the editorial PhDnet Meeting 2007 16 PhDnet during the last year. -

The Justice in Policing Act of 2020 in the U.S

June 23, 2020 Honorable Nancy Pelosi Speaker of the House 1236 Longworth House Office Building Washington, DC 20515 Honorable Kevin McCarthy Republican Leader 2468 Rayburn House Office Building Washington, DC 20515 Dear Speaker Pelosi and Leader McCarthy: Since the killing of George Floyd just one month ago, our country has seen protests grow, attitudes shift, and calls for change intensify. We in the music and entertainment communities believe that Black lives matter and have long decried the injustices endured by generations of Black citizens. We are more determined than ever to push for federal, state, and local law enforcement programs that truly serve their communities. Accordingly, we are grateful for movement of the Justice in Policing Act of 2020 in the U.S. House of Representatives and urge its quick passage. The Justice in Policing Act is not about marginal change; it takes bold steps that will make a real, positive difference for law enforcement and the communities they serve. We celebrate the long- overdue rejection of qualified immunity, emphasizing that law enforcement officers themselves are not above the law – that bad cops must be held accountable and victims must have recourse. We applaud the provisions to ban chokeholds and no-knock warrants, to establish a national police misconduct registry, to collect data and improve investigations into police misconduct, to promote de-escalation practices, to establish comprehensive training programs, and to update and enhance standards and practices. This legislation will not only promote justice; it will establish a culture of responsibility, fairness, and respect deserving of the badge. Our communities and nation look to you to take a stand in this extraordinary moment and we respectfully ask that you vote YES on the Justice in Policing Act of 2020. -

Social Media Use in Higher Education: a Review

education sciences Review Social Media Use in Higher Education: A Review Georgios Zachos *, Efrosyni-Alkisti Paraskevopoulou-Kollia and Ioannis Anagnostopoulos Department of Computer Science and Biomedical Informatics, School of Sciences, University of Thessaly, 35131 Lamia, Greece; [email protected] (E.-A.P.-K.); [email protected] (I.A.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +30-223-102-8628 Received: 14 August 2018; Accepted: 1 November 2018; Published: 5 November 2018 Abstract: Nowadays, social networks incessantly influence the lives of young people. Apart from entertainment and informational purposes, social networks have penetrated many fields of educational practices and processes. This review tries to highlight the use of social networks in higher education, as well as points out some factors involved. Moreover, through a literature review of related articles, we aim at providing insights into social network influences with regard to (a) the learning processes (support, educational processes, communication and collaboration enhancement, academic performance) from the side of students and educators; (b) the users’ personality profile and learning style; (c) the social networks as online learning platforms (LMS—learning management system); and (d) their use in higher education. The conclusions reveal positive impacts in all of the above dimensions, thus indicating that the wider future use of online social networks (OSNs) in higher education is quite promising. However, teachers and higher education institutions have not yet been highly activated towards faster online social networks’ (OSN) exploitation in their activities. Keywords: social media; social networks; higher education 1. Introduction Within the last decade, online social networks (OSN) and their applications have penetrated our daily life. -

Ca. 156.04 KB

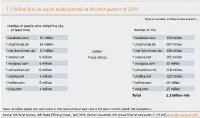

1.3 billion hits on social media portals in the first quarter of 2010 - Figures rounded, multiple choice answers - Number of people who visited the site … at least once Number of hits *.facebook.com 15 million *.facebook.com 330 million *.stayfriends.de 14 million *.stayfriends.de 107 million *.wer-kennt-wen.de 11 million … visited *.wer-kennt-wen.de 338 million *.meinvz.net 6 million these site(s) … *.meinvz.net 195 million *.myspace.com 6 million *.myspace.com 33 million *.schuelervz.net 6 million *.schuelervz.net 118 million *.studivz.net 5 million *.studivz.net 123 million *.twitter.com 5 million *.twitter.com 20 million *.xing.com 4 million *.xing.com 25 million Total 1.3 billion hits Basis: 44 million people who went online in their leisure time at least once in the past 3 months (AGOF, GfK calculations) Source: GfK Panel Services (GfK Media Efficiency Panel), April 2010, German households with private Internet connection (n=15,000) www.gfk-compact.com Explosive growth on previous year’s period Number of people who visited the site ... at least once - Figures in %, multiple choice answers - *.facebook.com 35 32 *.stayfriends.de *.wer-kennt-wen.de 25 26 *.meinvz.net 19 *.myspace.com 13 14 14 *.schuelervz.net 12 13 11 12 12 10 9 9 *.studivz.net 7 *.twitter.com 3 *.xing.com Q1/2009 Q1/2010 Basis: 44 million people who went online in their leisure time at least once in the past 3 months (AGOF, GfK calculations) Source: GfK Panel Services (GfK Media Efficiency Panel), April 2010, German households with private Internet connection (n=15,000) www.gfk-compact.com Intensive cross-over use by social communities Cross-usage - Figures in %, multiple choice answers – … % of people who visited … also visited … Key to table (example): 47% of Facebook users also visited “Stayfriends” in the first quarter of 2010; 50% of “Stayfriends” subscribers also visited Facebook facebook. -

An Exporter's Guide to the UK

MANAGING SOCIAL MEDIA IN EUROPE Social media overview and tips An Exporter’sto making yourself Guide heard in Europe to the UK An overview of the UK export environment from the perspective of American SMEs Share this Ebook @ www.ibtpartners.com An ibt partners presentation© INSIDE YOUR EBOOK ibt partners, the go-to provider for companies seeking an optimal online presence in Europe and the USA. IS THIS EBOOK RIGHT FOR ME? 3 SOCIAL MEDIA USE IN EUROPE 4 TOP SOCIAL NETWORKS BY COUNTRY 5 MANAGING GLOBAL NETWORKS IN EUROPE 6 MANAGING LOCAL NETWORKS IN EUROPE 7 FACEBOOK 8 GOOGLE+ 9 TWITTER 10 LINKEDIN 11 OPTIMIZE YOUR EUROPEAN ONLINE PRESENCE 12 NEXT STEPS, ABOUT IBT PARTNERS AND USEFUL LINKS 13 Produced by the ibt partners publications team. More resources available at: http://www.ibtpartners.com/resources @ Managing social media in Europe www.ibtpartners.com p.2 IS THIS EBOOK RIGHT FOR ME? Having an active social media strategy in your main export markets is crucial to European trade development. Together with country specific websites, it is the easiest, quickest and most cost effective route to developing internationally. You should be reading this ebook, if you want to : Gain an understanding of the most popular social networks in Europe Effectively manage your social media strategy in Europe Speak to your target European audience Generate local demand and sales online Be easily accessible for clients in Europe Own your brand in Europe This ebook is both informative and practical. We will provide you with insight, understanding and most importantly, the capacity to implement and optimize your local online marketing strategy.