Studivz: Social Networking in the Surveillance Society

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Social Media Tool Analysis

Social Media Tool Analysis John Saxon TCO 691 10 JUNE 2013 1. Orkut Introduction Orkut is a social networking website that allows a user to maintain existing relationships, while also providing a platform to form new relationships. The site is open to anyone over the age of 13, with no obvious bent toward one group, but is primarily used in Brazil and India, and dominated by the 18-25 demographic. Users can set up a profile, add friends, post status updates, share pictures and video, and comment on their friend’s profiles in “scraps.” Seven Building Blocks • Identity – Users of Orkut start by establishing a user profile, which is used to identify themselves to other users. • Conversations – Orkut users can start conversations with each other in a number of way, including an integrated instant messaging functionality and through “scraps,” which allows users to post on each other’s “scrapbooks” – pages tied to the user profile. • Sharing – Users can share pictures, videos, and status updates with other users, who can share feedback through commenting and/or “liking” a user’s post. • Presence – Presence on Orkut is limited to time-stamping of posts, providing other users an idea of how frequently a user is posting. • Relationships – Orkut’s main emphasis is on relationships, allowing users to friend each other as well as providing a number of methods for communication between users. • Reputation – Reputation on Orkut is limited to tracking the number of friends a user has, providing other users an idea of how connected that user is. • Groups – Users of Orkut can form “communities” where they can discuss and comment on shared interests with other users. -

Los Angeles Lawyer June 2010 June2010 Issuemaster.Qxp 5/13/10 12:26 PM Page 5

June2010_IssueMaster.qxp 5/13/10 12:25 PM Page c1 2010 Lawyer-to-Lawyer Referral Guide June 2010 /$4 EARN MCLE CREDIT PLUS Protecting Divorce Web Site Look and Estate and Feel Planning page 40 page 34 Limitations of Privacy Rights page 12 Revoking Family Trusts page 16 The Lilly Ledbetter Fair Pay Act Strength of page 21 Character Los Angeles lawyers Michael D. Schwartz and Phillip R. Maltin explain the effective use of character evidence in civil trials page 26 June2010_IssueMaster.qxp 5/13/10 12:42 PM Page c2 Every Legal Issue. One Legal Source. June2010_IssueMaster.qxp 5/13/10 12:25 PM Page 1 Interim Dean Scott Howe and former Dean John Eastman at the Top 100 celebration. CHAPMAN UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF LAW PROUDLY ANNOUNCES OUR RANKING AMONG THE TOP 100 OF ONE UNIVERSITY DRIVE, ORANGE, CA 92866 www.chapman.edu/law June2010_IssueMaster.qxp 5/13/10 12:25 PM Page 2 0/&'*3. ."/:40-65*0/4 Foepstfe!Qspufdujpo Q -"8'*3.$-*&/54 Q"$$&445007&3130'&44*0/"- -*"#*-*5:1307*%&34 Q0/-*/&"11-*$"5*0/4'03 &"4:$0.1-&5*0/ &/%034&%130'&44*0/"--*"#*-*5:*/463"/$,&3 Call 1-800-282-9786 today to speak to a specialist. 5 ' -*$&/4&$ 4"/%*&(003"/(&$06/5:-04"/(&-&44"/'3"/$*4$0 888")&3/*/463"/$&$0. June2010_IssueMaster.qxp 5/13/10 12:26 PM Page 3 FEATURES 26 Strength of Character BY MICHAEL D. SCHWARTZ AND PHILLIP R. MALTIN Stringent rules for the admission of character evidence in civil trials are designed to prevent jurors from deciding a case on the basis of which party is more likeable 34 Parting of the Ways BY HOWARD S. -

Seamless Interoperability and Data Portability in the Social Web for Facilitating an Open and Heterogeneous Online Social Network Federation

Seamless Interoperability and Data Portability in the Social Web for Facilitating an Open and Heterogeneous Online Social Network Federation vorgelegt von Dipl.-Inform. Sebastian Jürg Göndör geb. in Duisburg von der Fakultät IV – Elektrotechnik und Informatik der Technischen Universität Berlin zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades Doktor der Ingenieurwissenschaften - Dr.-Ing. - genehmigte Dissertation Promotionsausschuss: Vorsitzender: Prof. Dr. Thomas Magedanz Gutachter: Prof. Dr. Axel Küpper Gutachter: Prof. Dr. Ulrik Schroeder Gutachter: Prof. Dr. Maurizio Marchese Tag der wissenschaftlichen Aussprache: 6. Juni 2018 Berlin 2018 iii A Bill of Rights for Users of the Social Web Authored by Joseph Smarr, Marc Canter, Robert Scoble, and Michael Arrington1 September 4, 2007 Preamble: There are already many who support the ideas laid out in this Bill of Rights, but we are actively seeking to grow the roster of those publicly backing the principles and approaches it outlines. That said, this Bill of Rights is not a document “carved in stone” (or written on paper). It is a blog post, and it is intended to spur conversation and debate, which will naturally lead to tweaks of the language. So, let’s get the dialogue going and get as many of the major stakeholders on board as we can! A Bill of Rights for Users of the Social Web We publicly assert that all users of the social web are entitled to certain fundamental rights, specifically: Ownership of their own personal information, including: • their own profile data • the list of people they are connected to • the activity stream of content they create; • Control of whether and how such personal information is shared with others; and • Freedom to grant persistent access to their personal information to trusted external sites. -

Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2020

Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2020 Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2020 Nic Newman with Richard Fletcher, Anne Schulz, Simge Andı, and Rasmus Kleis Nielsen Supported by Surveyed by © Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism / Digital News Report 2020 4 Contents Foreword by Rasmus Kleis Nielsen 5 3.15 Netherlands 76 Methodology 6 3.16 Norway 77 Authorship and Research Acknowledgements 7 3.17 Poland 78 3.18 Portugal 79 SECTION 1 3.19 Romania 80 Executive Summary and Key Findings by Nic Newman 9 3.20 Slovakia 81 3.21 Spain 82 SECTION 2 3.22 Sweden 83 Further Analysis and International Comparison 33 3.23 Switzerland 84 2.1 How and Why People are Paying for Online News 34 3.24 Turkey 85 2.2 The Resurgence and Importance of Email Newsletters 38 AMERICAS 2.3 How Do People Want the Media to Cover Politics? 42 3.25 United States 88 2.4 Global Turmoil in the Neighbourhood: 3.26 Argentina 89 Problems Mount for Regional and Local News 47 3.27 Brazil 90 2.5 How People Access News about Climate Change 52 3.28 Canada 91 3.29 Chile 92 SECTION 3 3.30 Mexico 93 Country and Market Data 59 ASIA PACIFIC EUROPE 3.31 Australia 96 3.01 United Kingdom 62 3.32 Hong Kong 97 3.02 Austria 63 3.33 Japan 98 3.03 Belgium 64 3.34 Malaysia 99 3.04 Bulgaria 65 3.35 Philippines 100 3.05 Croatia 66 3.36 Singapore 101 3.06 Czech Republic 67 3.37 South Korea 102 3.07 Denmark 68 3.38 Taiwan 103 3.08 Finland 69 AFRICA 3.09 France 70 3.39 Kenya 106 3.10 Germany 71 3.40 South Africa 107 3.11 Greece 72 3.12 Hungary 73 SECTION 4 3.13 Ireland 74 References and Selected Publications 109 3.14 Italy 75 4 / 5 Foreword Professor Rasmus Kleis Nielsen Director, Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism (RISJ) The coronavirus crisis is having a profound impact not just on Our main survey this year covered respondents in 40 markets, our health and our communities, but also on the news media. -

Confronting Antisemitism in Modern Media, the Legal and Political Worlds an End to Antisemitism!

Confronting Antisemitism in Modern Media, the Legal and Political Worlds An End to Antisemitism! Edited by Armin Lange, Kerstin Mayerhofer, Dina Porat, and Lawrence H. Schiffman Volume 5 Confronting Antisemitism in Modern Media, the Legal and Political Worlds Edited by Armin Lange, Kerstin Mayerhofer, Dina Porat, and Lawrence H. Schiffman ISBN 978-3-11-058243-7 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-067196-4 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-067203-9 DOI https://10.1515/9783110671964 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. For details go to https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Library of Congress Control Number: 2021931477 Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. © 2021 Armin Lange, Kerstin Mayerhofer, Dina Porat, Lawrence H. Schiffman, published by Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston The book is published with open access at www.degruyter.com Cover image: Illustration by Tayler Culligan (https://dribbble.com/taylerculligan). With friendly permission of Chicago Booth Review. Printing and binding: CPI books GmbH, Leck www.degruyter.com TableofContents Preface and Acknowledgements IX LisaJacobs, Armin Lange, and Kerstin Mayerhofer Confronting Antisemitism in Modern Media, the Legal and Political Worlds: Introduction 1 Confronting Antisemitism through Critical Reflection/Approaches -

Chladni Und Die Entwicklung Der Akustik Von 1750-1860

Science Networks· Historical Studies Band 19 Herausgegeben von Erwin Hiebert und Hans WuBing In Zusammenarbeit mit: K. Anderson, Aarhus 1. Gray, Milton Keynes D. Barkan, Pasadena R. Halleux, Liege H.J.M. Bos, Utrecht S. Hildebrandt, Bonn U. Bottazzini, Bologna E. Knobloch, Berlin 1.Z. Buchwald, Toronto Ch. Meinel, Regensburg K. Chemla, Paris W. Purkert, Leipzig S.S. Demidov, Moskva D. Rowe, Mainz E.A. Fellmann, Basel A.I. Sabra, Cambridge M. Folkerts, Munchen R.H. Stuewer, Minneapolis P. Galison, Cambridge v.P. Vizgin, Moskva I. Grattan-Guinness, Bengeo Dieter Ullmann Chladni und die Entwicklung der Akustik von 1750-1860 1996 Birkhauser Verlag Basel· Boston· Berlin Autorenadresse: Dr. Dieter Ullmann Institut fiir Mathematik Universitat Potsdam Postfach 601553 D-I4415 Potsdam A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the Library of Congress, Washington D.C., USA Deutsche Bibliothek - CIP -Einheitsaufnahme Ullmann, Dieter: Chladni und die Entwicklung der Akustik : 1750-1860 I Dieter Ullmann. - Basel; Boston; Berlin: Birkhauser, 1996 (Science networks: Vol. 19) ISBN-13: 978-3-0348-9941-3 e-ISBN-13: 978-3-0348-9195-0 DOl: 10.1007/978-3-0348-9195-0 NE:GT Dieses Werk ist urheberrechtlich geschiitzt. Die dadurch begriindeten Rechte, insbesondere die der Ubersetzung, des Nachdrucks, des Vortrags, der Entnahme von Abbildungen und Tabellen, der Funksendung, der Mikroverfilmung oder der Vervielfaltigung auf anderen Wegen und der Speicherung in Datenverarbeitungsanlagen, bleiben, auch bei nur auszugsweiser Verwertung, vorbehalten. Eine Vervielfaltigung dieses Werkes oder von Teilen dieses Werkes ist auch im Einzelfall nur in den Grenzen der gesetzlichen Bestimmungen des Urheberrechtsgesetzes in der jeweils geltenden Fassung zulassig. -

Dissertation Online Consumer Engagement

DISSERTATION ONLINE CONSUMER ENGAGEMENT: UNDERSTANDING THE ANTECEDENTS AND OUTCOMES Submitted by Amy Renee Reitz Department of Journalism and Technical Communication In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Colorado State University Fort Collins, Colorado Summer 2012 Doctoral Committee: Advisor: Jamie Switzer Co-Advisor: Ruoh-Nan Yan Jennifer Ogle Donna Rouner Peter Seel Copyright by Amy Renee Reitz 2012 All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT ONLINE CONSUMER ENGAGEMENT: UNDERSTANDING THE ANTECEDENTS AND OUTCOMES Given the adoption rates of social media and specifically social networking sites among consumers and companies alike, practitioners and academics need to understand the role of social media within a company’s marketing efforts. Specifically, understanding the consumer behavior process of how consumers perceive features on a company’s social media page and how these features may lead to loyalty and ultimately consumers’ repurchase intentions is critical to justify marketing efforts to upper management. This study focused on this process by situating online consumer engagement between consumers’ perceptions about features on a company’s social media page and loyalty and (re)purchase intent. Because online consumer engagement is an emerging construct within the marketing literature, the purpose of this study was not only to test the framework of online consumer engagement but also to explore the concept of online consumer engagement within a marketing context. The study refined the definition of online -

Get Noticed Promoting Your Article for Maximum Impact Get Noticed 2 GET NOTICED

Get Noticed Promoting your article for maximum impact GET NOTICED 2 GET NOTICED More than one million scientific articles are published each year, and that number is rising. So it’s increasingly important for you to find ways to make your article stand out. While there is much that publishers and editors can do to help, as the paper’s author you are often best placed to explain why your findings are so important or novel. This brochure shows you what Elsevier does and what you can do yourself to ensure that your article gets the attention it deserves. GET NOTICED 3 1 PREPARING YOUR ARTICLE SEO Optimizing your article for search engines – Search Engine Optimization (SEO) – helps to ensure it appears higher in the results returned by search engines such as Google and Google Scholar, Elsevier’s Scirus, IEEE Xplore, Pubmed, and SciPlore.org. This helps you attract more readers, gain higher visibility in the academic community and potentially increase citations. Below are a few SEO guidelines: • Use keywords, especially in the title and abstract. • Add captions with keywords to all photographs, images, graphs and tables. • Add titles or subheadings (with keywords) to the different sections of your article. For more detailed information on how to use SEO, see our guideline: elsevier.com/earlycareer/guides GIVE your researcH THE IMpact it deserVes Thanks to advances in technology, there are many ways to move beyond publishing a flat PDF article and achieve greater impact. You can take advantage of the technologies available on ScienceDirect – Elsevier’s full-text article database – to enhance your article’s value for readers. -

Magazine of the Max Planck Phd

m et agazine of the max planck phd n Publisher: Max Planck PhDnet (2008) Editorial board: Verena Conrad, MPI for Biological Cybermetics, Tübingen Corinna Handschuh, MPI for Evolutionary Anthroplology, Leipzig Julia Steinbach, MPI for Biogeochemistry, Jena Peter Buschkamp, MPI for Extraterrestrial Physics, Garching Franziska Hartung, MPI for Experimental Biology, Göttingen Design: offspring Silvana Schott, MPI for Biogeochemistry, Jena Table of Contents Dear reader, you have the third issue of the Offspring So, here you see the first issue of this new Dear Reader 3 in your hands, the official magazine of Offspring and we hope you enjoy reading the Max Planck PhDnet. This magazine it! The main topic of this issue is “Success”, A look back ... 4 was started in 2005 to communicate the for instance you may read interviews with ... and forward 5 network‘s activities and to provide rele- MPI-scientists at different levels of their Introduction of the new Steering Group 6 vant information to PhD students at all career, giving their personal perception of institutes. Therefore, the first issues mainly scientific success, telling how they celeb- Success story 8 contained reports about previous meetings rate success and how they cope with fai- Questionnaire on Scientific Success 10 and announcements of future events. lure; you will learn how two foreign PhD What the ?&%@# is Bologna? 14 students succeeded in getting along in However, at the PhD representatives’ mee- Germany in their first months – and of ting in Leipzig, November 2006, a new Workgroups of the PhDnet 15 course about the successful work of the work group was formed as the editorial PhDnet Meeting 2007 16 PhDnet during the last year. -

Social Media Use in Higher Education: a Review

education sciences Review Social Media Use in Higher Education: A Review Georgios Zachos *, Efrosyni-Alkisti Paraskevopoulou-Kollia and Ioannis Anagnostopoulos Department of Computer Science and Biomedical Informatics, School of Sciences, University of Thessaly, 35131 Lamia, Greece; [email protected] (E.-A.P.-K.); [email protected] (I.A.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +30-223-102-8628 Received: 14 August 2018; Accepted: 1 November 2018; Published: 5 November 2018 Abstract: Nowadays, social networks incessantly influence the lives of young people. Apart from entertainment and informational purposes, social networks have penetrated many fields of educational practices and processes. This review tries to highlight the use of social networks in higher education, as well as points out some factors involved. Moreover, through a literature review of related articles, we aim at providing insights into social network influences with regard to (a) the learning processes (support, educational processes, communication and collaboration enhancement, academic performance) from the side of students and educators; (b) the users’ personality profile and learning style; (c) the social networks as online learning platforms (LMS—learning management system); and (d) their use in higher education. The conclusions reveal positive impacts in all of the above dimensions, thus indicating that the wider future use of online social networks (OSNs) in higher education is quite promising. However, teachers and higher education institutions have not yet been highly activated towards faster online social networks’ (OSN) exploitation in their activities. Keywords: social media; social networks; higher education 1. Introduction Within the last decade, online social networks (OSN) and their applications have penetrated our daily life. -

Ca. 156.04 KB

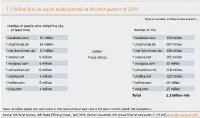

1.3 billion hits on social media portals in the first quarter of 2010 - Figures rounded, multiple choice answers - Number of people who visited the site … at least once Number of hits *.facebook.com 15 million *.facebook.com 330 million *.stayfriends.de 14 million *.stayfriends.de 107 million *.wer-kennt-wen.de 11 million … visited *.wer-kennt-wen.de 338 million *.meinvz.net 6 million these site(s) … *.meinvz.net 195 million *.myspace.com 6 million *.myspace.com 33 million *.schuelervz.net 6 million *.schuelervz.net 118 million *.studivz.net 5 million *.studivz.net 123 million *.twitter.com 5 million *.twitter.com 20 million *.xing.com 4 million *.xing.com 25 million Total 1.3 billion hits Basis: 44 million people who went online in their leisure time at least once in the past 3 months (AGOF, GfK calculations) Source: GfK Panel Services (GfK Media Efficiency Panel), April 2010, German households with private Internet connection (n=15,000) www.gfk-compact.com Explosive growth on previous year’s period Number of people who visited the site ... at least once - Figures in %, multiple choice answers - *.facebook.com 35 32 *.stayfriends.de *.wer-kennt-wen.de 25 26 *.meinvz.net 19 *.myspace.com 13 14 14 *.schuelervz.net 12 13 11 12 12 10 9 9 *.studivz.net 7 *.twitter.com 3 *.xing.com Q1/2009 Q1/2010 Basis: 44 million people who went online in their leisure time at least once in the past 3 months (AGOF, GfK calculations) Source: GfK Panel Services (GfK Media Efficiency Panel), April 2010, German households with private Internet connection (n=15,000) www.gfk-compact.com Intensive cross-over use by social communities Cross-usage - Figures in %, multiple choice answers – … % of people who visited … also visited … Key to table (example): 47% of Facebook users also visited “Stayfriends” in the first quarter of 2010; 50% of “Stayfriends” subscribers also visited Facebook facebook. -

An Exporter's Guide to the UK

MANAGING SOCIAL MEDIA IN EUROPE Social media overview and tips An Exporter’sto making yourself Guide heard in Europe to the UK An overview of the UK export environment from the perspective of American SMEs Share this Ebook @ www.ibtpartners.com An ibt partners presentation© INSIDE YOUR EBOOK ibt partners, the go-to provider for companies seeking an optimal online presence in Europe and the USA. IS THIS EBOOK RIGHT FOR ME? 3 SOCIAL MEDIA USE IN EUROPE 4 TOP SOCIAL NETWORKS BY COUNTRY 5 MANAGING GLOBAL NETWORKS IN EUROPE 6 MANAGING LOCAL NETWORKS IN EUROPE 7 FACEBOOK 8 GOOGLE+ 9 TWITTER 10 LINKEDIN 11 OPTIMIZE YOUR EUROPEAN ONLINE PRESENCE 12 NEXT STEPS, ABOUT IBT PARTNERS AND USEFUL LINKS 13 Produced by the ibt partners publications team. More resources available at: http://www.ibtpartners.com/resources @ Managing social media in Europe www.ibtpartners.com p.2 IS THIS EBOOK RIGHT FOR ME? Having an active social media strategy in your main export markets is crucial to European trade development. Together with country specific websites, it is the easiest, quickest and most cost effective route to developing internationally. You should be reading this ebook, if you want to : Gain an understanding of the most popular social networks in Europe Effectively manage your social media strategy in Europe Speak to your target European audience Generate local demand and sales online Be easily accessible for clients in Europe Own your brand in Europe This ebook is both informative and practical. We will provide you with insight, understanding and most importantly, the capacity to implement and optimize your local online marketing strategy.