Summary of 2019 Massachusetts Piping Plover Census Data

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Summary of 2017 Massachusetts Piping Plover Census Data

SUMMARY OF THE 2017 MASSACHUSETTS PIPING PLOVER CENSUS Bill Byrne, MassWildlife SUMMARY OF THE 2017 MASSACHUSETTS PIPING PLOVER CENSUS ABSTRACT This report summarizes data on abundance, distribution, and reproductive success of Piping Plovers (Charadrius melodus) in Massachusetts during the 2017 breeding season. Observers reported breeding pairs of Piping Plovers present at 147 sites; 180 additional sites were surveyed at least once, but no breeding pairs were detected at them. The population increased 1.4% relative to 2016. The Index Count (statewide census conducted 1-9 June) was 633 pairs, and the Adjusted Total Count (estimated total number of breeding pairs statewide for the entire 2017 breeding season) was 650.5 pairs. A total of 688 chicks were reported fledged in 2017, for an overall productivity of 1.07 fledglings per pair, based on data from 98.4% of pairs. Prepared by: Natural Heritage & Endangered Species Program Massachusetts Division of Fisheries & Wildlife 2 SUMMARY OF THE 2017 MASSACHUSETTS PIPING PLOVER CENSUS INTRODUCTION Piping Plovers are small, sand-colored shorebirds that nest on sandy beaches and dunes along the Atlantic Coast from North Carolina to Newfoundland. The U.S. Atlantic Coast population of Piping Plovers has been federally listed as Threatened, pursuant to the U.S. Endangered Species Act, since 1986. The species is also listed as Threatened by the Massachusetts Division of Fisheries and Wildlife pursuant to Massachusetts’ Endangered Species Act. Population monitoring is an integral part of recovery efforts for Atlantic Coast Piping Plovers (U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service 1996, Hecht and Melvin 2009a, b). It allows wildlife managers to identify limiting factors, assess effects of management actions and regulatory protection, and track progress toward recovery. -

New Horizons Woolly Bears See Page 2

S e p t e m b e r – D e c e m b e r 2010 A N e w s l e t t e r f o r t h e M e M b e r s o f M A s s A u d u b o N Inside This Issue 2 A Vision for the Future 4 New Land Opportunities 6 Creating Conservation Communities 8 Bird Conservation in Action 9 Stay Connected 13 Young Environmental Leaders Inside Every Issue 10 ready, set, Go Outside! Seeds 11 Exploring the Nature of Massachusetts: Fruits 14 Volunteer Spotlight: Dick and Sally Avery 15 The Natural Inquirer: New Horizons Woolly Bears see page 2 Connections online · Regional news · Exclusive online content www.massaudubon.org/connections A Vision for the Future A Newsletter for the MeMbers of MAss AuduboN Volume 8, Number 3 Editorial Team: Hilary Koeller, Jan Kruse, Susannah Lund, Ann Prince, and Hillary G. Truslow We invite your comments, photographs, and suggestions. Please send correspondence to: Mass Audubon Connections, 208 South Great Road, Lincoln, MA 01773, tel: 781-259-9500, or e-mail: [email protected]. For information about becoming a member, or for questions regarding your membership, contact: Member Services, Mass Audubon, 208 South Great Road, Lincoln, MA 01773 tel: 781-259-9500 or 800-AUDUBON, or e-mail: [email protected]. Connections is published three times each year in January, May, and September. Please recycle this newsletter by giving it to a friend by Laura Johnson, President or t donating i to a school, library, or business. -

Massachusetts Summary of Proposed Changes

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service John H. Chafee Coastal Barrier Resources System (CBRS) Unit C00, Clark Pond, Massachusetts Summary of Proposed Changes Type of Unit: System Unit County: Essex Congressional District: 6 Existing Map: The existing CBRS map depicting this unit is: ■ 025 dated October 24, 1990 Proposed Boundary Notice of Availability: The U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service (Service) opened a public comment period on the proposed changes to Unit C00 via Federal Register notice. The Federal Register notice and the proposed boundary (accessible through the CBRS Projects Mapper) are available on the Service’s website at www.fws.gov/cbra. Establishment of Unit: The Coastal Barrier Resources Act (Pub. L. 97-348), enacted on October 18, 1982 (47 FR 52388), originally established Unit C00. Historical Changes: The CBRS map for this unit has been modified by the following legislative and/or administrative actions: ■ Coastal Barrier Improvement Act (Pub. L. 101-591) enacted on November 16, 1990 (56 FR 26304) For additional information on historical legislative and administrative actions that have affected the CBRS, see: https://www.fws.gov/cbra/Historical-Changes-to-CBRA.html. Proposed Changes: The proposed changes to Unit C00 are described below. Proposed Removals: ■ One structure and undeveloped fastland near Rantoul Pond along Fox Creek Road ■ Four structures and undeveloped fastland located to the north of Argilla Road and east of Fox Creek Proposed Additions: ■ Undeveloped fastland and associated aquatic habitat along Treadwell Island Creek, -

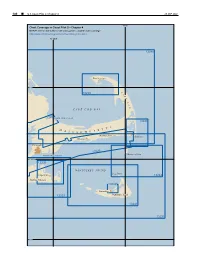

Outer Cape Cod and Nantucket Sound

186 ¢ U.S. Coast Pilot 2, Chapter 4 26 SEP 2021 70°W Chart Coverage in Coast Pilot 2—Chapter 4 NOAA’s Online Interactive Chart Catalog has complete chart coverage http://www.charts.noaa.gov/InteractiveCatalog/nrnc.shtml 70°30'W 13246 Provincetown 42°N C 13249 A P E C O D CAPE COD BAY 13229 CAPE COD CANAL 13248 T S M E T A S S A C H U S Harwich Port Chatham Hyannis Falmouth 13229 Monomoy Point VINEYARD SOUND 41°30'N 13238 NANTUCKET SOUND Great Point Edgartown 13244 Martha’s Vineyard 13242 Nantucket 13233 Nantucket Island 13241 13237 41°N 26 SEP 2021 U.S. Coast Pilot 2, Chapter 4 ¢ 187 Outer Cape Cod and Nantucket Sound (1) This chapter describes the outer shore of Cape Cod rapidly, the strength of flood or ebb occurring about 2 and Nantucket Sound including Nantucket Island and the hours later off Nauset Beach Light than off Chatham southern and eastern shores of Martha’s Vineyard. Also Light. described are Nantucket Harbor, Edgartown Harbor and (11) the other numerous fishing and yachting centers along the North Atlantic right whales southern shore of Cape Cod bordering Nantucket Sound. (12) Federally designated critical habitat for the (2) endangered North Atlantic right whale lies within Cape COLREGS Demarcation Lines Cod Bay (See 50 CFR 226.101 and 226.203, chapter 2, (3) The lines established for this part of the coast are for habitat boundary). It is illegal to approach closer than described in 33 CFR 80.135 and 80.145, chapter 2. -

A Newsletter for the Members of Mass Audubon Message from the President

July–September 2016 A Newsletter for the Members of Mass Audubon Message from the President During the spring of 1916, Dr. George W. Field…offered the use of “his large estate at Moose Hill, Sharon, as a Bird Sanctuary, it being hoped that it might be developed as a model… s we celebrate 100 Years of Wildlife Sanctuaries and our hundred properties this year, the above passage in the first Bulletin of the Massachusetts Audubon ”Society reveals remarkable A foresight—though its authors could never have imagined where we stand today as a 21st-century conservation leader. That original 225-acre estate in Sharon evolved into Moose Hill Wildlife Sanctuary, Mass Audubon’s first, which today welcomes visitors to an oasis of almost 2,000 protected acres. Yet Moose Hill is but one bright thread in a tapestry of sanctuaries spreading from the Cape and Islands to the Berkshires. The terms wildlife and sanctuary are both evocative words on their own. But in partnership, they serve as a powerful illustration of the sum being greater than its parts. Our foundational commitment was to the protection and promotion of birds and their habitats, and that legacy endures at each and every Mass Audubon wildlife sanctuary. In 2016, our sanctuaries and nature centers not only support a much fuller concept of species protection and biodiversity, but also serve as hubs for carrying out that work in service to the three core elements of our mission: conservation, education, and advocacy. And just as important, they exist as community-based resources for members and those in the general public eager to forge their own connections to nature through an ever-broader array of programs and activities for all ages, backgrounds, and abilities. -

Inventory of Habitat Modifications to Sandy Beaches ME-NY Rice 2015

Inventory of Habitat Modifications to Sandy Beaches in the U.S. Atlantic Coast Breeding Range of the Piping Plover (Charadrius melodus) prior to Hurricane Sandy: Maine to the North Shore and Peconic Estuary of New York1 Tracy Monegan Rice Terwilliger Consulting, Inc. June 2015 Recovery Task 1.2 of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) Recovery Plan for the piping plover (Charadrius melodus) prioritizes the maintenance of “natural coastal formation processes that perpetuate high quality breeding habitat,” specifically discouraging the “construction of structures or other developments that will destroy or degrade plover habitat” (Task 1.21), “interference with natural processes of inlet formation, migration, and closure” (Task 1.22), and “beach stabilization projects including snowfencing and planting of vegetation at current or potential plover breeding sites” (Task 1.23) (USFWS 1996, pp. 65-67). This assessment fills a data need to identify such habitat modifications that have altered natural coastal processes and the resulting abundance, distribution, and condition of currently existing habitat in the breeding range. Four previous studies provided these data for the United States (U.S.) continental migration and overwintering range of the piping plover (Rice 2012a, 2012b) and the southern portion of the U.S. Atlantic Coast breeding range (Rice 2014, 2015a). This assessment provides these data for one habitat type – namely sandy beaches within the northern portion of the breeding range along the Atlantic coast of the U.S. prior to Hurricane Sandy. A separate report assessed tidal inlet habitat in the same geographic range prior to Hurricane Sandy (Rice 2015b). Separate reports will assess the status of these two habitats in the northern and southern portions of the U.S. -

Least Tern & Endangered Species Sternula Antillarum

Natural Heritage Least Tern & Endangered Species Sternula antillarum Program State Status: Special Concern www.mass.gov/nhesp Federal Status: None Massachusetts Division of Fisheries & Wildlife Tern’s voice is high and shrill. Its repertoire includes zwreep and kit-kit-kit-kit alarm calls, k’ee-you-hud-dut recognition call, and the male’s ki-dik contact call. SIMILAR SPECIES IN MASSACHUSETTS: Common (Sterna hirundo), Roseate (Sterna dougallii), and Arctic (Sterna paradisaea) Terns are all much larger, have entirely black foreheads and crowns in breeding plumage, have different colored bills and, proportionately, have much longer tails. Photo by B. Byrne, MDFW Diminutive yet feisty, the Least Tern is a spring and summer colonial nester on Massachusetts’ sandy beaches. For nesting, it favors sites with little or no vegetation. This preference coincides with humans’ most desired spots for recreation and development, resulting in conflicts of use and loss of considerable Least Tern habitat in the past century. Currently, the Least Tern is considered a Species of Special Concern in Massachusetts, and continued management of nesting habitat and colonies is necessary to protect the state’s population. DESCRIPTION: The Least Tern measures 21-23 cm in length and weighs 40-62 g. In breeding plumage, the adult has a black cap and eyestripe, white forehead, pale Figure 1. Distribution of present and historic Least Tern gray upperparts, white underparts, a black-tipped, nesting colonies in Massachusetts. yellow-orange bill, and yellow-orange legs. Outside the breeding season, the crown and eyestripe become DISTRIBUTION AND MIGRATION: The Least Tern flecked with white, a dark bar forms on the wing, and breeds in North, Middle, and South America and the the bill and legs darken. -

Summary of the 2016 Massachusetts Piping Plover Census

SUMMARY OF THE 2016 MASSACHUSETTS PIPING PLOVER CENSUS B. Byrne, MassWildlife SUMMARY OF THE 2016 MASSACHUSETTS PIPING PLOVER CENSUS ABSTRACT This report summarizes data on abundance, distribution, and reproductive success of Piping Plovers (Charadrius melodus) in Massachusetts during the 2016 breeding season. Observers reported breeding pairs of Piping Plovers present at 145 sites; 172 additional sites were surveyed at least once, but no breeding pairs were detected at them. The population decreased 5.5% relative to 2015. The Index Count (statewide census conducted 1-9 June) was 628.5 pairs, and the Adjusted Total Count (estimated total number of breeding pairs statewide for the entire 2016 breeding season) was 649 pairs. A total of 912 chicks were reported fledged in 2016, for an overall productivity of 1.44 fledglings per pair, based on data from 97.5% of pairs. Prepared by: Natural Heritage & Endangered Species Program Massachusetts Division of Fisheries & Wildlife 2 SUMMARY OF THE 2016 MASSACHUSETTS PIPING PLOVER CENSUS INTRODUCTION Piping Plovers are small, sand-colored shorebirds that nest on sandy beaches and dunes along the Atlantic Coast from North Carolina to Newfoundland. The U.S. Atlantic Coast population of Piping Plovers has been federally listed as Threatened, pursuant to the U.S. Endangered Species Act, since 1986. The species is also listed as Threatened by the Massachusetts Division of Fisheries and Wildlife pursuant to Massachusetts’ Endangered Species Act. Population monitoring is an integral part of recovery efforts for Atlantic Coast Piping Plovers (U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service 1996, Hecht and Melvin 2009a, b). It allows wildlife managers to identify limiting factors, assess effects of management actions and regulatory protection, and track progress toward recovery. -

A Guide to Mass Audubon's

Places to Explore A Guide to Mass Audubon’s Wildlife Sanctuaries, Nature Centers, and Museums Table of Contents Introduction 1 Map of Wildlife Sanctuaries, Nature Centers, and Museums 8 Icon Key 10 Greater Boston 11 Central Massachusetts 46 Blue Hills Trailside Museum, Milton 12 Broad Meadow Brook, Worcester 47 Boston Nature Center, Mattapan 13 Burncoat Pond, Spencer 48 Broadmoor, Natick 14 Cook’s Canyon, Barre 49 Drumlin Farm, Lincoln 15 Eagle Lake, Holden 50 Habitat Education Center, Belmont 16 Flat Rock, Fitchburg 51 Moose Hill, Sharon 17 Lake Wampanoag, Gardner 52 Museum of American Bird Art, Canton 18 Lincoln Woods, Leominster 53 Stony Brook, Norfolk 19 Nashoba Brook, Westford 54 Waseeka, Hopkinton 20 Pierpont Meadow, Dudley 55 Poor Farm Hill, New Salem 56 North Shore 21 Rocky Hill, Groton 57 Eastern Point, Gloucester 22 Rutland Brook, Petersham 58 Endicott, Wenham 23 Wachusett Meadow, Princeton 59 Ipswich River, Topsfield 24 Joppa Flats Education Center, Connecticut Newburyport 25 60 River Valley Marblehead Neck, Marblehead 26 Arcadia, Easthampton Nahant Thicket, Nahant 27 & Northampton 61 Rough Meadows, Rowley 28 Conway Hills, Conway 62 Graves Farm, Williamsburg South of Boston 29 & Whately 63 Allens Pond, Dartmouth & Westport 30 High Ledges, Shelburne 64 Attleboro Springs, Attleboro 31 Laughing Brook, Hampden 65 Daniel Webster, Marshfield 32 Lynes Woods, Westhampton 66 Great Neck, Wareham 33 Richardson Brook, Tolland 67 North Hill Marsh, Duxbury 34 Road’s End, Worthington 68 North River, Marshfield 35 West Mountain, Plainfield -

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Proposed Boundary Notice of Availability: John H. Chafee Coastal Barrier Resources System (CBRS

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service John H. Chafee Coastal Barrier Resources System (CBRS) Unit C00, Clark Pond, Massachusetts Summary of Proposed Changes Type of Unit: System Unit County: Essex Congressional District: 6 Existing Map: The existing CBRS map depicting this unit is: ■ 025 dated October 24, 1990 Proposed Boundary Notice of Availability: The U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service (Service) opened a public comment period on the proposed changes to Unit C00 via Federal Register notice. The Federal Register notice and the proposed boundary (accessible through the CBRS Projects Mapper) are available on the Service’s website at www.fws.gov/cbra. Establishment of Unit: The Coastal Barrier Resources Act (Pub. L. 97-348), enacted on October 18, 1982 (47 FR 52388), originally established Unit C00. Historical Changes: The CBRS map for this unit has been modified by the following legislative and/or administrative actions: ■ Coastal Barrier Improvement Act (Pub. L. 101-591) enacted on November 16, 1990 (56 FR 26304) For additional information on historical legislative and administrative actions that have affected the CBRS, see: https://www.fws.gov/cbra/Historical-Changes-to-CBRA.html. Proposed Changes: The proposed changes to Unit C00 are described below. Proposed Removals: ■ One structure and undeveloped fastland near Rantoul Pond along Fox Creek Road ■ Four structures and undeveloped fastland located to the north of Argilla Road and east of Fox Creek Proposed Additions: ■ Undeveloped fastland and associated aquatic habitat along Treadwell Island Creek, -

The Shifting Sands of Sampson's Island

A SHORT HISTORY OF THE OSTERVILLE/WIANNO CUT THE SHIFTING SANDS OF SAMPSON'S ISLAND June 20, 2019 – Cotuit Chronicles Lecture Series ONE ISLAND TWO NAMES TWO VILLAGES TWO OWNERS COTUIT CHRONICLES 2 3 THE NEWEST LAND ON THE CAPE COTUIT CURRENTS 4 EARLY USES • Salt Hay • Storage of spars , rigging and cargo for coastal shipping • Forage for cattle • Clams • Access to Oyster Island (Oyster Harbors/Grand Island) COTUIT CHRONICLES 5 WHO WAS SAMPSON? Squire Josiah Sampson (1754-1829) inherited the island from his mother Desiree Crocker. The Crockers were given the land by the “Proprietors” in 1708. Sampson is best known for “Sampson’s Folly,” his home on Old King’s Road. Daniel Childs, a salt maker, bought the island from Sampson’s descendants in two transactions in 1837 and 1839 for $105. It isn’t known if he used Sampson’s as a saltworks COTUIT CHRONICLES 6 1. John Crocker was granted the island in 1708 by the “proprietors. OWNERS OF 2. Desiree Crocker, great granddaughter of John Crocker bequeathed the island to her son, Joseph Sampson SAMPSON’S ISLAND 3. Daniel Childs, salt maker, bought the island in two transactions in 1837 and 1839 from Sampson’s cousin Ezra Crocker and Josiah Sampson Jr. 4. Charlotte Davidson, a summer resident of Cotuit, bought Sampson’s from Child’s descendants for $275 in 1885 5. Horace Sears, Boston textile manufacturer, bought the island from Davidson in 1906 6. His secretary, Harry L. Bailey, inherited Sears’ estate and the island in 1923. 7. Bailey, persuaded by Cotuit bird watcher Alva Morrison, donated the island to the Massachusetts Audubon Society in 1953 COTUIT CHRONICLES 7 1. -

Places We Love

J U LY –S EPTEMBER 2015 A N EWSLETTER FOR THE M E M BERS OF M A SS A UDUBO N Inside This Issue 1-3 Places We Love: An Inside View 3-4 Field Notes: Richardson Brook Wildlife Sanctuary, a Quiet Gem Summers are Free for Military Families at Wildlife Sanctuaries Goat Encounters at Habitat Controlled Burns Conserve Rare Habitats on Nantucket 5 Teen Programs: Bridging the Gap 6 Bird Conservation: Return of the Osprey 7 Volunteer Spotlight: Blue Hill Trailside Museum’s Bridget Waldbaum Advocacy: Catching Rain, Saving Money 8 Climate: Sustainable Summer Checklist 9 By the Numbers: A More Accessible and Inclusive Mass Audubon 10 Program Sampler 11 Exploring the Nature of Massachusetts: Carnivorous Plants 12 Outdoor Almanac 13 Ready, Set, Go Outside!: Peaceful Ponds 14 The Natural Inquirer: Crabs Connect with us Places We Love: An Inside View Facebook Twitter Instagram YouTube Flickr Blogs massaudubon.org View from Brown Hill, Wachusett Meadow Wildlife Sanctuary, Princeton South Esker Trail, Ipswich River Places We Love: South of Boston Allens Pond, Dartmouth An Inside View “Tree Top View on our Quansett Trail. It’s a restful perch on cool stone high above a thicket of clethra, under a canopy of graceful oak ith thousands of miles of trails to explore on our wildlife where you can be still, listening to life thronging all around—frogs, Wsanctuaries, there is no shortage of amazing locations to visit. birds, crickets. It’s remote without isolation.” – No group knows this better than Mass Audubon’s sanctuary directors. Gina Purtell We asked each of them to describe a spot on our properties that is near and dear to their heart.