Arxiv:1303.3453V1 [Astro-Ph.SR] 14 Mar 2013

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Limits from the Hubble Space Telescope on a Point Source in SN 1987A

Limits from the Hubble Space Telescope on a Point Source in SN 1987A The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Graves, Genevieve J. M., Peter M. Challis, Roger A. Chevalier, Arlin Crotts, Alexei V. Filippenko, Claes Fransson, Peter Garnavich, et al. 2005. “Limits from the Hubble Space Telescopeon a Point Source in SN 1987A.” The Astrophysical Journal 629 (2): 944–59. https:// doi.org/10.1086/431422. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:41399924 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA The Astrophysical Journal, 629:944–959, 2005 August 20 # 2005. The American Astronomical Society. All rights reserved. Printed in U.S.A. LIMITS FROM THE HUBBLE SPACE TELESCOPE ON A POINT SOURCE IN SN 1987A Genevieve J. M. Graves,1, 2 Peter M. Challis,2 Roger A. Chevalier,3 Arlin Crotts,4 Alexei V. Filippenko,5 Claes Fransson,6 Peter Garnavich,7 Robert P. Kirshner,2 Weidong Li,5 Peter Lundqvist,6 Richard McCray,8 Nino Panagia,9 Mark M. Phillips,10 Chun J. S. Pun,11,12 Brian P. Schmidt,13 George Sonneborn,11 Nicholas B. Suntzeff,14 Lifan Wang,15 and J. Craig Wheeler16 Received 2005 January 27; accepted 2005 April 26 ABSTRACT We observed supernova 1987A (SN 1987A) with the Space Telescope Imaging Spectrograph (STIS) on the Hubble Space Telescope (HST ) in 1999 September and again with the Advanced Camera for Surveys (ACS) on the HST in 2003 November. -

1 NASA Goddard Space Flight Center

Source of Acquisition 1 NASA Goddard Space Flight Center \> SN 1987A AFTER 18 YEARS: MID-INFRARED GEMINI and SPITZER OBSERVATIONS OF THE REMNANT Patrice Bouchet1,2, Eli Dwek3, John Danziger4, Richard G. Arendt 5, I. James M. De Buizer', Sangwook Park7, Nicholas B. SuntzefF2, Robert P. Kirshners, and Peter Challis ABSTRACT We present high resolution 11.7 and 18.3 pm mid-IR images of SN 1987A obtained on day 6526 since the explosion with the Thermal-Region Camera and Spectrograph (T-ReCS) attached to the Gemini South 8m telescope. The 11.7 pm flux has increased significantly since our last observations on day 6067. The images clearly show that all the emission arises from the equatorial ring (ER). Nearly contemporaneous spectra obtained on day 6184 with the MIPS at 24 pm, on day 6130 with the IRAC in 3.6- 8 pm region, and on day 6190 with the IRS in the 12-37 ,urn instruments on board the Spitzer Space Telescope's show that the emission consists of thermal emission from silicate dust that condensed out in the red giant wind of the progenitor star. The dust temperature is 1662:; K, and the emitting dust mass is (2.6:;;:) x MB.Lines of [Ne 111 12.82 pm and [Ne 1111 15.56 pm are clearly present in the Spitzer spectrum, as well as a weak [Si 113 34.8 pm line. We also detect two lines near 26 pm which we tentatively ascribe to [Fe 117 25.99 pm and [0 IV] 25.91 pm. Comparison of the mid-IR Gemini 11.7 pm image with X-ray images obtained by Chandra, UV- optical images obtained by HST, and radio synchrotron images obtained by the ATCA show generally good correlation of the images across all wavelengths. -

The Distance to the Large Magellanic Cloud

Proceedings Astronomy from 4 perspectives 1. Cosmology The distance to the large magellanic cloud Stefan V¨olker (Jena) In the era of modern cosmology it is necessary to determine the Hubble constant as precise as possible. Therefore it is important to know the distance to the Large Mag- ellanic Cloud (LMC), because this distance forms the fundament of the cosmological distance ladder. The determination of the LMC's distance is an suitable project for highschool students and will be presented in what follows. Calculating the distance to the LMC using the supernova SN 1987 A [1, 2] By combining the angular size α of an object with its absolute size R, one can calculate the distance d (at least for our cosmological neighborhood) using the equation R R d = ≈ (1) tan α α and the approximation d R. In the case of the SN 1987 A students can measure the angular size of the circumstellar ring on the Hubble Space Telescope (HST) image (Figure 1). The absolute size of the ring can be derived from the delay time due to light-travel effects seen in the emission light curve (also Figure 1). Once the supernova exploded, the UV-flash started 1,00 0,75 0,50 intensity (normalized) 0,25 0 0 500 1000 time t/d ESA/Hubble tP1' tP2' Figure 1: left: HST picture of the SN 1987 A; right: emission light curve of the circumstellar [2, 3] propagating and reached the whole ring at the same time, which started emitting immediately. The additional distance x is linked to the delay time by the equation x = c · ∆t = c · (t 0 − t 0 ). -

Gas and Dust in the Magellanic Clouds

Gas and dust in the Magellanic clouds A Thesis Submitted for the Award of the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Physics To Mangalore University by Ananta Charan Pradhan Under the Supervision of Prof. Jayant Murthy Indian Institute of Astrophysics Bangalore - 560 034 India April 2011 Declaration of Authorship I hereby declare that the matter contained in this thesis is the result of the inves- tigations carried out by me at Indian Institute of Astrophysics, Bangalore, under the supervision of Professor Jayant Murthy. This work has not been submitted for the award of any degree, diploma, associateship, fellowship, etc. of any university or institute. Signed: Date: ii Certificate This is to certify that the thesis entitled ‘Gas and Dust in the Magellanic clouds’ submitted to the Mangalore University by Mr. Ananta Charan Pradhan for the award of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the faculty of Science, is based on the results of the investigations carried out by him under my supervi- sion and guidance, at Indian Institute of Astrophysics. This thesis has not been submitted for the award of any degree, diploma, associateship, fellowship, etc. of any university or institute. Signed: Date: iii Dedicated to my parents ========================================= Sri. Pandab Pradhan and Smt. Kanak Pradhan ========================================= Acknowledgements It has been a pleasure to work under Prof. Jayant Murthy. I am grateful to him for giving me full freedom in research and for his guidance and attention throughout my doctoral work inspite of his hectic schedules. I am indebted to him for his patience in countless reviews and for his contribution of time and energy as my guide in this project. -

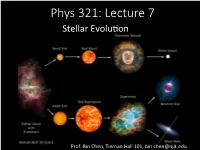

Phys 321: Lecture 7 Stellar Evolu�On

Phys 321: Lecture 7 Stellar Evolu>on Prof. Bin Chen, Tiernan Hall 101, [email protected] Stellar Evoluon • Formaon of protostars (covered in Phys 320; briefly reviewed here) • Pre-main-sequence evolu>on (this lecture) • Evolu>on on the main sequence (this lecture) • Post-main-sequence evolu>on (this lecture) • Stellar death (next lecture) The Interstellar Medium and Star Formation the cloud’s internal kinetic energy, given by The Interstellar Medium and Star Formation the cloud’s internal kinetic energy, given by 3 K NkT, 3 = 2 The Interstellar MediumK andNkT, Star Formation = 2 where N is the total number2 ofTHE particles. FORMATIONwhere ButNNisis the just total OF number PROTOSTARS of particles. But N is just M Mc N c , Our understandingN , of stellar evolution has= µm developedH significantly since the 1960s, reaching = µmH the pointwhere whereµ is the much mean of molecular the life weight. history Now, of by a the star virial is theorem, well determined. the condition for This collapse success has been where µ is the mean molecular weight.due to advances Now,(2K< byU the in) becomes observational virial theorem, techniques, the condition improvements for collapse in our knowledge of the physical | | (2K< U ) becomes processes important in stars, and increases in computational2 power. In the remainder of this | | 3MckT 3 GMc chapter, we will present an overview of< the lives. of stars, leaving de(12)tailed discussions 2 µmH 5 Rc of s3oMmeckTspecia3l pGMhasces of evolution until later, specifically stellar pulsation, supernovae, The radius< may be replaced. by using the initial mass density(12) of the cloud, ρ , assumed here µmH 5 Rc 0 and comtop beac constantt objec throughoutts (stellar theco cloud,rpses). -

Twenty Years of SN 1987A

Astronomical Science Twenty Years of Supernova 1987A Claes Fransson1 Prize in 2002 (shared with Riccardo scope covers. Some of the smaller tele- Roberto Gilmozzi 2 Giacconi for X-ray astronomy and Ray- scopes took their chance. The 61-cm Per Gröningsson1 mond Davis Jr. for solar neutrinos). Bochum telescope on La Silla was used, Reinhard Hanuschik 2 The most important implication of the on a nearly daily basis for more than Karina Kjær 2 neutrinos was that it confirmed the a year, to measure optical spectroscopy Bruno Leibundgut 2 hydrodynamic core collapse, releasing with photometric accuracy. Since the Jason Spyromilio 2 about 3 × 1053 ergs of gravitational LMC is circumpolar for most southern energy, mainly in neutrinos of all kinds. observatories, this also meant that This confirmed the predictions by Col- we have an uninterrupted record of the 1 Stockholm University gate, Arnett and others from the 1960s. photometry and spectroscopy; else 2 ESO Among many other results, the few we would have missed part of the peak neutrinos showed that the electron-neu- phase, which lasted into May of 1987. trino mass has to be rather small (m ≤ By July, the first conference on SN 1987A ve The unique supernova SN 1987A has 20 eV, superseded in the meantime by had already taken place at ESO in Gar- been a bonanza for astrophysicists. direct experiments) as no time-delay ching (Danziger 1987) to be followed by It provided several observational ‘firsts’, effects could be measured. Also, the fact several others during that year and fol- like the detection of neutrinos from that there is no structure in the neutrino lowing years. -

The Star Newsletter

THE HOT STAR NEWSLETTER ? An electronic publication dedicated to A, B, O, Of, LBV and Wolf-Rayet stars and related phenomena in galaxies No. 41 June/July 1998 editor: Philippe Eenens http://www.astro.ugto.mx/∼eenens/hot/ [email protected] http://www.star.ucl.ac.uk/∼hsn/index.html Contents of this newsletter From the Editor . 1 Abstracts of 24 accepted papers . 2 Abstracts of 2 submitted paper . 16 Abstracts of 2 proceedings papers . 17 Book ......................................................................18 Meetings ...................................................................20 From the editor This issue covers two months of publications and is dominated by η Car, other LBVs and B[e] stars. Other papers tell us about massive stars in the Galactic Center and R136, OB stars, polarimetry, wind models and [WC] central stars of Planetary Nebulae. We also present a book and remind readers about future meetings: two special sessions during IAU symposium 193 in Mexico (on HD5980 and on the XMEGA campaign) as well as IAU colloquium 175 in Spain in June 1999 (on Be stars). 1 Accepted Papers On the Multiplicity of η Carinae Henny J.G.L.M. Lamers1,2, Mario Livio1, Nino Panagia1,3, & Nolan R. Walborn1 1 Space Telescope Science Institute, 3700 San Martin Drive, Baltimore, MD 21218, USA 2 Astronomical Institute and SRON Laboratory for Space Research, Princetonplein 2, 3584CC Utrecht, The Netherlands 3 On assignment from the Astrophysics Division, Space Science Department of ESA. The nebula around the luminous blue variable η Car is extremely N-rich and C,O-poor, indicative of CNO-cycle products. On the other hand, the recent HST-GHRS observation of the nucleus of η Car shows the spectrum of a star with stellar-wind lines of C ii,C iv, Si ii, Si iv etc. -

Astroparficle,Physics,, With,Mev,Neutrinos

University(of(Virginia,(HEP(Seminar,(April(21st(2015( Astropar(cle,physics,, with,MeV,neutrinos, Shunsaku(Horiuchi(( (Center(for(Neutrino(Physics,(Virginia(Tech)( Image(credit:(NASA/ESA( Contents, • IntroducJon:(why(astrophysical(neutrinos(now?( • Topic(1:(Supernova(neutrinos( – GalacJc(events:(rich(physics(and(astronomy( – Detectability(beyond(GalacJc(events( • Topic(2:(Dark(maPer(neutrinos( – Two(searches,(two(constraints( • Summary( UVa,(April(21st(2015( Shunsaku(Horiuchi((Virginia(Tech)( 2( Neutrinos,as,messenger,par(cles Neutrinos(are(great(messenger(parJcles:( • allow(us(to(see(opJcally(thick((to(photons)(regions( • experience(liPle(aPenuaJon(through(cosmic(space( • travel(in(straight(lines( Source Neutrinos gamma(rays( Cosmic(raysCosmic(rays( MagneJc(field UVa,(April(21st(2015 Shunsaku(Horiuchi((Virginia(Tech) 3( Neutrino,detec(on:,Cherenkov,, Use(the(Cherenkov(light(to(reconstruct(the(original(neutrino( ν" IceCube( Eν >(10(GeV( Muon(range(increases( the(effecJve(volume(( lepton( e( Du>a,et,al,,PRD,(2001),, SuperVKamiokande( Eν(>(few(MeV(( Volume(~(50(kton(of(water( Volume(~(1(Gton(of(ice( UVa,(April(21st(2015( Shunsaku(Horiuchi((Virginia(Tech)( 4( Neutrino,sources, RadioacJve(decay( Sun((x1)( Nuclear( Supernova((x1)( reactors( ParJcle( Astrophysical( accelerator( accelerator( Likely' Cosmic(background( Atmospheric( +(others?( UVa,(April(21st(2015(Shunsaku(Horiuchi((IPMU)((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((Shunsaku(Horiuchi((Virginia(Tech)( -

Curriculum Vitae of You-Hua Chu

Curriculum Vitae of You-Hua Chu Address and Telephone Number: Institute of Astronomy and Astrophysics, Academia Sinica 11F of Astronomy-Mathematics Building, AS/NTU No.1, Sec. 4, Roosevelt Rd, Taipei 10617 Taiwan, R.O.C. Tel: (886) 02 2366 5300 E-mail address: [email protected] Academic Degrees, Granting Institutions, and Dates Granted: B.S. Physics Dept., National Taiwan University 1975 Ph.D. Astronomy Dept., University of California at Berkeley 1981 Professional Employment History: 2014 Sep - present Director, Institute of Astronomy and Astrophysics, Academia Sinica 2014 Jul - present Distinguished Research Fellow, Institute of Astronomy and Astrophysics, Academia Sinica 2014 Jul - present Professor Emerita, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign 2005 Aug - 2011 Jul Chair of Astronomy Dept., University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign 1997 Aug - 2014 Jun Professor, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign 1992 Aug - 1997 Jul Research Associate Professor, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign 1987 Jan - 1992 Aug Research Assistant Professor, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign 1985 Feb - 1986 Dec Graduate College Scholar, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign 1984 Sep - 1985 Jan Lindheimer Fellow, Northwestern University 1982 May - 1984 Jun Postdoctoral Research Associate, University of Wisconsin at Madison 1981 Oct - 1982 May Postdoctoral Research Associate, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign 1981 Jun - 1981 Aug Postdoctoral Research Associate, University of California at Berkeley Committees Served: -

The Lives and Death-Throes of Massive Stars Iau Symposium 329

Proceedings of the International Astronomical Union IAU Symposium No. 329 IAU Symposium IAU Symposium 28 November–2 December Research on massive stars is undergoing a period of rapid progress Auckland, New Zealand with long-held convictions being shown to be incomplete. While 329 these stars are relatively few in number, they are the main driver of chemical and dynamical evolution in galaxies through their stellar winds and explosive deaths in core-collapse supernovae. Furthermore the impact of massive stars is widely recognized in 28 November– 329 28 November–2 December many areas, as they are often used as tools to interpret the 2 December The Lives and conditions and processes arising in different environments. In Auckland, New Zealand The Lives and parallel, the development of new instrumentation, analysis Auckland, Death-Throes of techniques and dedicated surveys across all possible wavelengths New Zealand have delivered large amounts of exquisite new data. These data are Death-Throes of now providing a harsh test for the current state-of-the-art Massive Stars theoretical calculations of massive star birth, evolution and death. IAU Symposium 329 covers these topics and is therefore an invaluable resource for researchers in the fi eld of massive stars and Massive Stars their evolution. Proceedings of the International Astronomical Union Editor in Chief: Dr Piero Benvenuti This series contains the proceedings of major scientifi c meetings held by the International Astronomical Union. Each volume contains a series of articles on a topic of current interest in astronomy, giving a timely overview of research in the fi eld. With The Lives and contributions by leading scientists, these books are at a level Death-Throes of suitable for research astronomers and graduate students. -

Final Report the Goddard High Resolution Spectrograph Scientific

NASA-CR-204980 Final Report The Goddard High Resolution Spectrograph Scientific Support Contract NAS5-32494 December 13, 1993 - December 12, 1996 Computer Sciences Corporation 4061 Powder Mill Road Calverton, MD 20705 GHRS SSC Final Report i Contents List of Acronyms iv I. Introduction II. Summary of Activities 4 1 Project Support - Subtask 1 4 1.1 Proposal Preparation and Tracking ..................... 4 1.2 SMOV and Post-COSTAR Calibration ................... 5 1.3 In-Orbit Performance Papers ........................ 7 1.4 Operations Studies .............................. 7 1.4.1 GHRS Efficiency ........................... 7 1.4.2 GHRS Low-Noise Orbits ....................... 8 1.5 Meetings and Information Distribution ................... 9 1.6 Public Information .............................. 9 1.7 The World Wide Web ............................ 10 1.8 The GHRS Science Symposium ....................... 11 2 Data Analysis Facility - Subtask 2 12 2.1 Facility Management ............................. 12 2.2 GHRS Archive ................................ 13 2.3 GHRS Team Software ............................ 15 2.4 General Software Support .......................... 15 2.5 Data Bases .................................. 16 2.6 Data Reduction and Analysis Assistance .................. 17 3 Extragalactic Imagery- Subtask 3 17 3.1 Analysis of R136 ............................... 17 3.2 Eta Carinae .................................. 19 3.3 Star Clusters in M33 ............................. 19 3.3.1 NGC 595 ............................... 20 3.3,2 -

Hydrodynamic Simulations Unravel the Progenitor-Supernova-Remnant

Astronomy & Astrophysics manuscript no. paper c ESO 2019 December 9, 2019 Hydrodynamic simulations unravel the progenitor-supernova-remnant connection in SN 1987A S. Orlando1, M. Ono2,3, S. Nagataki2,3, M. Miceli4,1, H. Umeda5, G. Ferrand2,3, F. Bocchino1, O. Petruk6,7, G. Peres4,1, K. Takahashi8, and T. Yoshida5 1 INAF – Osservatorio Astronomico di Palermo, Piazza del Parlamento 1, I-90134 Palermo, Italy e-mail: [email protected] 2 Astrophysical Big Bang Laboratory, RIKEN Cluster for Pioneering Research, 2-1 Hirosawa, Wako, Saitama 351-0198, Japan 3 RIKEN Interdisciplinary Theoretical & Mathematical Science Program (iTHEMS), 2-1 Hirosawa, Wako, Saitama 351-0198, Japan 4 Dip. di Fisica e Chimica, Universit`adegli Studi di Palermo, Piazza del Parlamento 1, 90134 Palermo, Italy 5 Department of Astronomy, Graduate School of Science, University of Tokyo, Tokyo 113-0033, Japan 6 Institute for Applied Problems in Mechanics and Mathematics, Naukova Street 3-b, Lviv 79060, Ukraine 7 Astronomical Observatory, National University, Kyryla and Methodia St 8, Lviv 79008, Ukraine 8 Max-Planck-Institut f¨ur Gravitationsphysik (Albert-Einstein-Institute), Am M¨uhlenberg 1, D-14476 Potsdam-Golm, Germany Received date / Accepted date ABSTRACT Context. Massive stars end their lives with catastrophic supernova (SN) explosions. Key information on the explosion processes and on the progenitor stars can be extracted from observations of supernova remnants (SNRs), the outcome of SNe. Deciphering these observations however is challenging because of the complex morphology of SNRs. Aims. We aim at linking the dynamical and radiative properties of the remnant of SN 1987A to the geometrical and physical charac- teristics of the parent aspherical SN explosion and to the internal structure of its progenitor star.