Estimating the Prevalence of Treated Epilepsy Using Administrative Health Data and Its Validity: ESSENCE Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Scientific Program

Scientific Program June 16 (Thu) Educational Session 1:Innovative treatment of medical oncology 08:30-09:40, Crystal Ballroom A Chairs: Joon Oh Park (Samsung Medical Center) Myung Ah Lee (The Catholic University of Korea College of Medicine) 1) Innovative treatment of malignant lymphoma Seok Jin Kim (Samsung Medical Center) 2) Innovative treatment of lung cancer Eun Joo Kang (Korea University College of Medicine) 3) Innovative treatment of ovarian cancer Jae Ho Byun (The Catholic University of Korea College of Medicine) 2:Current status and future perspectives of radiotherapy in hepatocellular carcinoma 08:30-09:40, Crystal Ballroom B Chairs: Jae-Sung Kim (Seoul National University College of Medicine) Joo-Young Kim (National Cancer Center) 1) Radiotherapeutic strategies in management of hepatocellular carcinoma Jinsil Seong (Yonsei University College of Medicine) 2) Recent updates on precision radiotherapy for hepatocellular carcinoma Hee Chul Park (Samsung Medical Center) 3) Radiation induced hepatic toxicity and how to avoid it Tae Hyun Kim (National Cancer Center) 3: Updated management of peritoneal surface maliganancy 08:30-09:40, Crystal Ballroom C Chairs: Jong-Inn Lee (Korea Institute of Radiological & Medical Sciences) Sang-Yoon Park (National Cancer Center) 1) Peritoneactomy Myong Cheol Lim (National Cancer Center) 2) Updated management of peritoneal surface malignancy: HIPEC Seung Hyuk Baik (Yonsei University College of Medicine) 3) EPIC for gastric cancer Oh Kyoung Kwon (Kyungpook National University School of Medicine) Young -

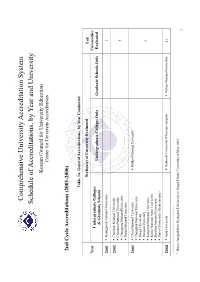

Schedule of Accreditations, by Year and University

Comprehensive University Accreditation System Schedule of Accreditations, by Year and University Korean Council for University Education Center for University Accreditation 2nd Cycle Accreditations (2001-2006) Table 1a: General Accreditations, by Year Conducted Section(s) of University Evaluated # of Year Universities Undergraduate Colleges Undergraduate Colleges Only Graduate Schools Only Evaluated & Graduate Schools 2001 Kyungpook National University 1 2002 Chonbuk National University Chonnam National University 4 Chungnam National University Pusan National University 2003 Cheju National University Mokpo National University Chungbuk National University Daegu University Daejeon University 9 Kangwon National University Korea National Sport University Sunchon National University Yonsei University (Seoul campus) 2004 Ajou University Dankook University (Cheonan campus) Mokpo National University 41 1 Name changed from Kyungsan University to Daegu Haany University in May 2003. 1 Andong National University Hanyang University (Ansan campus) Catholic University of Daegu Yonsei University (Wonju campus) Catholic University of Korea Changwon National University Chosun University Daegu Haany University1 Dankook University (Seoul campus) Dong-A University Dong-eui University Dongseo University Ewha Womans University Gyeongsang National University Hallym University Hanshin University Hansung University Hanyang University Hoseo University Inha University Inje University Jeonju University Konkuk University Korea -

PLATELET-001 All Participating Site IRB/EC List Ver.1.0 07May2020 Confidential

BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance Supplemental material placed on this supplemental material which has been supplied by the author(s) BMJ Open Yonsei University College of Medicine Gangnam Severance Hospital PLATELET-001_All Participating Site IRB/EC List_Ver.1.0_07May2020 Confidential PLATELET-001 Site Institutional Review Board(IRB) / Site Name Address No. Ethic Committee(EC) Yonsei University College of Medicine Gangnam Severance Yonsei University College of Medicine Yonsei University Gangnam Severance Hospital 01 Hospital, 211, Eonju-ro, Gangnam-gu, Seoul, Republic of Korea, Gangnam Severance Hospital Institutional Review Board 06273 Gachon University Gil Medical Center Gachon University Gil Medical Center, 21, Namdong-daero 02 Gachon University Gil Medical Center Institutional Review Board 774beon-gil, Namdong-gu, Incheon, Republic of Korea, 21565 Catholic Kwandong University Catholic Kwandong University International 25, Simgok-ro 100beon-gil, Seo-gu, Incheon, Republic of Korea, 03 International St.Mary`s Hospital St.Mary`s Hospital Institutional Review Board 22711 KyungHee University Hospital Kyung Hee University Korean Medicine Hospital Kyung Hee University Hospital at Gangdong, 892, Dongnam-ro, 04 at Gangdong at Gangdong Institutional Review Board Gangdong-gu, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 05278 Kangwon National University Hospital Kangwan National University Hospital, 156, Baengnyeong-ro, 05 Kangwan National University Hospital Institutional Review Board Chuncheon-si, -

Appreciations to Peer Reviewers for Journal of Korean Medical Science 2017

J Korean Med Sci. 2018 Mar 26;33(13):e114 https://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2018.33.e114 eISSN 1598-6357·pISSN 1011-8934 Editorial Appreciations to Peer Reviewers for Journal of Korean Medical Science 2017 Sung-Tae Hong , Editor-in-Chief, Journal of Korean Medical Science Department of Parasitology and Tropical Medicine, Seoul National University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea Received: Mar 21, 2018 The Journal of Korean Medical Science (JKMS) changed its online submission system to the Editorial Accepted: Mar 21, 2018 Manager® powered by the Aries Systems from 1 October 2017. In 2017, the submissions through Address for Correspondence: the old system were 910 and the new system were 227, total 1,137. A total of 320 (28.1%) of them Sung-Tae Hong, MD, PhD were overseas submissions. Overall accept rate was 27.8% in 2017. All of the submissions were Department of Parasitology and Tropical previewed and about half of them were requested to peer review. A total of 1,232 reviewers were Medicine, Seoul National University College of invited and 544 of them finished reviews. They were scored from 1 to 5 (5 is the best) for their Medicine, 103 Daehak-ro, Jongno-gu, review activities. Seoul 03080, Korea. E-mail: [email protected] The JKMS sincerely appreciates contributions of peer reviewers who critically reviewed and © 2018 The Korean Academy of Medical sent us their constructive comments. Thanks to their academic contributions, JKMS can Sciences. publish quality articles and invite global readers. We expect continuous good reviews that can This is an Open Access article distributed make JKMS more academic credits. -

Validation Study of the Official Korean Version of the Movement Disorder Society-Unified Parkinson’S Disease Rating Scale

JCN Open Access ERRATUM pISSN 1738-6586 / eISSN 2005-5013 / J Clin Neurol 2021;17(3):501-501 / https://doi.org/10.3988/jcn.2021.17.3.501 Validation Study of the Official Korean Version of the Movement Disorder Society-Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale Jinse Parka, Seong-Beom Kohb, Kyum-Yil Kwonc, Sang Jin Kimd, Jae Woo Kime, Joong-Seok Kimf, Kun-Woo Parkg, Jong Sam Paikh, Young H. Sohni, Jin-Young Ahnj, Tae-Beom Ahnk, Eungseok Ohl, Jinyoung Younm, Ji-Young Leen, Phil Hyu Leei, Wooyoung Jango, Han-Joon Kimp, Beom Seok Jeonp, Sun Ju Chungq, Jin Whan Chom, Sang-Myung Cheone, Suk Yun Kangr, Mee Young Parks, Seongho Parka, Young Eun Huht, Seok Jae Kangu, Hee-Tae Kimu aDepartment of Neurology, Inje University, Haeundae Paik Hospital, Busan, Korea bDepartment of Neurology, Korea University Guro Hosipital, Korea University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea cDepartment of Neurology, Soonchunhyang University Seoul Hospital, Soonchunhyang University School of Medicine, Seoul, Korea dDepartment of Neurology, Inje University Busan Paik Hospital, Busan, Korea eDepartment of Neurology, Dong-A University Hospital, Dong-A University College of Medicine, Busan, Korea fDepartment of Neurology, Seoul St. Mary's Hospital, The Catholic University of Korea College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea gDepartment of Neurology, Korea University Anam Hospital, Korea University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea hDepartment of Neurology, Inje University Sanggye Paik Hospital, Seoul, Korea iDepartment of Neurology, Severance Hospital, Yonsei University College of Medicine, -

2021 Global Korea Scholarship

2021 Global Korea Scholarship Application Guidelines for Graduate Degrees 2021 정부초청외국인 대학원 장학생 모집 요강 2021. 2. 1 2021 Global Korea Scholarship Application Guidelines for Graduate Degrees I. PROGRAM OBJECTIVES ○ Global Korea Scholarship is designed to provide international students with opportunities to study at higher educational institutions in Korea at graduate-level degrees, which will enhance international education exchange and deepen mutual friendship between Korea and participating countries. ※ As Korean Government Scholarship Programs have been integrated and branded as Global Korea Scholarship in 2010, the name is changed to GKS (Global Korea Scholarship). II. NUMBER OF EXPECTED GRANTEES ◈ Total Number of Expected Grantees Embassy Track University Track Degree Program Degree Program Classifica Total tion Korean Research Sub Research Sub Overseas Language Program Total Program Total General General Reg/Sci* Korean Teaching Professionals Quota 603 20 30 10 663 430 180 5 615 1,278 * Science & Engineering majors of Regional University applicants ◈ Embassy Track ○ Quota for General Applicants No. Country & Region Quota No. Country & Region Quota No. Country & Region Quota 1 Afghanistan 4 14 Belarus 2 27 Canada (Quebec) 2 2 Albania 1 15 Belgium 2 28 Chile 3 3 Algeria 2 16 Benin 1 29 China 31 4 Angola 2 17 Bolivia 2 30 Colombia 4 5 Argentina 3 18 Bosnia and Herzegovina 1 31 Comoros 1 6 Armenia 3 19 Botswana 2 32 Congo 1 7 Australia 1 20 Brazil 6 33 Costa Rica 3 8 Austria 1 21 Brunei 4 34 Cote d'Ivoire 4 9 Azerbaijan 6 22 Bulgaria 8 35 Croatia 1 10 Bahamas 1 23 Burkina Faso 1 36 Czech Republic 2 11 Bahrain 1 24 Burundi 1 37 Denmark 1 12 Bangladesh 5 25 Cambodia 10 38 Dominican Republic 3 13 Barbados 2 26 Canada 3 39 DR Congo 3 1 No. -

2021 Global Korea Scholarship

2021 Global Korea Scholarship Application Guidelines for Undergraduate Degrees 2021 정부초청외국인 학부 장학생 모집 요강 2020. 9. Table of Contents I. PROGRAM OBJECTIVES ........................................................................................................... 2 II. PROGRAM and EXPECTED GRANTEES .............................................................................. 2 III. AVAILABLE UNIVERSITIES AND FIELDS OF STUDY ................................................... 5 IV. ELIGIBILITY .............................................................................................................................. 6 V. REQUIRED DOCUMENTS ........................................................................................................ 9 VI. SELECTION PROCEDURES ................................................................................................. 10 VII. SCHOLARSHIP INFORMATION ........................................................................................ 14 VIII. PERIOD OF SCHOLARSHIP .............................................................................................. 15 IX. KOREAN LANGUAGE PROGRAM ..................................................................................... 16 X. OTHER IMPORTANT NOTES ................................................................................................ 17 XI. CONTACT INFORMATION .................................................................................................. 18 2021 GLOBAL KOREA SCHOLARSHIP Application Checklist ................................... -

Editorial Board

Editorial Board Editor-in-Chief Choon-Sik Park Soonchunhyang University, Korea Advisory Board Jean Bousquet Seung-Yull Cho Takeshi Fukuda The University of Montpellier, France Sungkyunkwan University, Korea Dokkyo University, Japan Chein Soo Hong Choon Shil Lee Ha-Baik Lee Yonsei University, Korea Sookmyung Women’s University, Korea Hanyang University, Korea Joon Sung Lee Sang-Il Lee Yang-Gi Min The Catholic University of Korea, Korea Sungkyunkwan University, Korea Seoul National University, Korea Sung Hak Park Yang Keun Rhee The Catholic University of Korea, Korea Chonbuk National University, Korea Associate Editors Stephen T Holgate Soo-Jong Hong Kyu-Earn Kim Southampton University, UK University of Ulsan, Korea Yonsei University, Korea Chun Geun Lee Kyung-Up Min Jae Won Oh Yale University, USA Seoul National University, Korea Hanyang University, Korea Hae-Sim Park Hirohisa Saito Ajou University, Korea National Research Institute for Child Health and Development, Japan Editorial Board Kangmo Ahn Walter Canonica Thomas B Casale Sungkyunkwan University, Korea University of Genova DIMI, Italy Creighton University, USA Hiok Hee Chng Sang Heon Cho You Sook Cho National University of Singapore, Singapore Seoul National University, Korea University of Ulsan, Korea In Seon Choi Hun-Jong Dhong Philippe A Eigenmann Chonnam National University, Korea Sungkyunkwan University, Korea University Hospital of Geneva, Switzerland James E Gern Woo Kyung Kim Yoon Keun Kim University of Wisconsin-Madison, USA Inje University, Korea Postech, Korea Young -

01. 2020-001(종설)-77.Hwp

Supplementary Table 1. List of responding participants Participants Affiliation Jang-Hyun Baek Department of Neurology, National Medical Center, Seoul, Korea Dong-Hyun Shim Department of Neurology, Samsung Changwon Hospital, Changwon, Korea Dong Geun Lee Department of Neurology, Sejong General Hospital, Bucheon, Korea Hee-Kwon Park Department of Neurology, Inha University Hospital, Incheon, Korea Woo-Keun Seo Department of Neurology and Stroke Center, Samsung Medical Center, Sungkyunkwan University, Seoul, Korea Joonsang Yoo Department of Neurology, Keimyung University Dongsan Medical Center, Daegu, Korea Jun Lee Department of Neurology, Yeungnam University Hospital, Daegu, Korea Jin Soo Lee Department of Neurology, Ajou University School of Medicine, Suwon, Korea Sam Yeol Ha Department of Neurology, Inje University Haeundae Paik Hospital, Busan, Korea Jeong-Jin Park Department of Neurology, Konkuk University Hospital, Seoul, Korea Si Baek Lee Department of Neurology, Uijeongbu St. Mary’s Hospital, Uijeongbu, Korea Jun Young Chang Department of Neurology, Asan Medical Center, University of Ulsan College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea Ho Geol Woo Department of Neurology, Soonchunhyang University Cheonan Hospital, Cheonan, Korea Sang Joon An Department of Neurology, Catholic Kwandong University International St. Mary’s Hospital, Incheon, Korea Ji Hoe Heo Department of Neurology, Severance Hospital, Yonsei University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea Joung-Ho Rha Department of Neurology, Inha University College of Medicine, Incheon, Korea Sun U. Kwon Department of Neurology, Asan Medical Center, University of Ulsan College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea Keun-Sik Hong Department of Neurology, Ilsan Paik Hospital, Inje University, Goyang, Korea Sang-Bae Ko Department of Neurology, Seoul National University Hospital Hong-Kyun Park Department of Neurology, Ilsan Paik Hospital, Inje University, Goyang, Korea Jong S. -

Professional Graduate School of Medicine

경희대영문요람원고_최종2_3 2012.2.24 5:1 PM 페이지222 004 Professional Graduate School School of Medicine Tel : +82 2 961 0274, 0301 Fax : +82 2 969 6958 E-mail : [email protected] URL : http://khusm.khu.ac.kr The School of Medicine seeks to impart students with a firm grasp of mental and physical health by basic and clinical studies. To accomplish this goal, the school offers a 4-year program in basic human science and clinical science. The first year of the program is devoted to a basic medical course such as Anatomy, Physiology, Biochemistry, Histology, Embryology, Neurology Genetics, Pathology, Pharmacology, Microbiology, Immunology, Preventive Medicine, and Parasitology. During the next three years, the students are trained to gain expertise in the various clinical subjects. Degree Requirements Year 1 The first year of program requires 45 credit hours of 30 class courses consisting primarily of basic medical sciences. The courses include Anatomy, Physiology, Biochemistry, Histology, Embryology, Behavioral Science, Genetics, Pathology, Pharmacology, Microbiology, Immunology, Preventive Medicine, and Parasitology. Year 2 The second year program mainly contains clinical lectures and practice. Students are asked to register for 46 credit hours of 25 class courses. Year 3 The third year program mainly contains clinical clerkships. Students are asked to register for 46 credit hours of 12 class courses. Year 4 The fourth year program contains clinical clerkships. Students are asked to register for 46 credit hours of 31 class courses. Courses Year 1 Anatomy, -

![Journal of Stroke 2019 Apr 17. [Epub Ahead of Print]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6079/journal-of-stroke-2019-apr-17-epub-ahead-of-print-5526079.webp)

Journal of Stroke 2019 Apr 17. [Epub Ahead of Print]

Journal of Stroke 2019 Apr 17. [Epub ahead of print] Supplementary Table 1. List of responding participants Participants Affiliation Jang-Hyun Baek Department of Neurology, National Medical Center, Seoul, Korea Dong-Hyun Shim Department of Neurology, Samsung Changwon Hospital, Sungkyunkwan University School of Medicine, Changwon, Korea Dong Geun Lee Department of Neurology, Sejong General Hospital, Bucheon, Korea Hee-Kwon Park Department of Neurology, Inha University Hospital, Incheon, Korea Woo-Keun Seo Department of Neurology and Stroke Center, Samsung Medical Center, Sungkyunkwan University School of Medicine, Seoul, Korea Joonsang Yoo Department of Neurology, Keimyung University Dongsan Medical Center, Daegu, Korea Jun Lee Department of Neurology, Yeungnam University Hospital, Daegu, Korea Jin Soo Lee Department of Neurology, Ajou University School of Medicine, Suwon, Korea Sam Yeol Ha Department of Neurology, Inje University Haeundae Paik Hospital, Busan, Korea Jeong-Jin Park Department of Neurology, Konkuk University Hospital, Seoul, Korea Si Baek Lee Department of Neurology, Uijeongbu St. Mary’s Hospital, College of Medicine, The Catholic University of Korea, Uijeongbu, Korea Jun Young Chang Department of Neurology, Asan Medical Center, University of Ulsan College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea Ho Geol Woo Department of Neurology, Soonchunhyang University Cheonan Hospital, Cheonan, Korea Sang Joon An Department of Neurology, International St. Mary’s Hospital, Catholic Kwandong University College of Medicine, Incheon, Korea Ji Hoe Heo -

Assessment of Korea's Orthopedic Research Activities in the Top 15

Original Article Clinics in Orthopedic Surgery 2019;11:237-243 • https://doi.org/10.4055/cios.2019.11.2.237 Assessment of Korea’s Orthopedic Research Activities in the Top 15 Orthopedic Journals, 2008–2017 Won Yong Shon, MD, Byung-Ho Yoon, MD*, Eun-Ae Jung, MS†, Jin Woo Kim, MD‡, Yong-Chan Ha, MD§, Seung Hwan Han, MDΙΙ, Hak-Sun Kim, MDΙΙ Department of Orthopedic Surgery, Bumin Hospital, Busan, *Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Seoul Paik Hospital, Inje University College of Medicine, Seoul, †Medical Library, Soonchunhyang University Bucheon Hospital, Bucheon, ‡Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Eulji University College of Medicine, Seoul, §Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Chung-Ang University College of Medicine, Seoul, ΙΙDepartment of Orthopaedic Surgery, Yonsei University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea Background: Bibliometrics is increasingly used to assess the quantity and quality of scientific research output in many research fields worldwide. This study aims to update Korea’s worldwide research productivity in the field of orthopedics using bibliometric methods and to provide Korean surgeons and researchers with insights into such research. Methods: Articles published in the top 15 orthopedic journals between 2008 and 2017 were retrieved using the Web of Science. The number of articles, citations and h-index (Hirsch index), funding sources, institutions, and journal patterns were analyzed. Results: Of the total 39,494 articles, Korea’s contribution accounted for 5.6% (2,161 articles), ranking fifth in the world in the number of publications. Korea ranked sixth (with 29,456) for total citations worldwide but ranked 17th (13.64) in terms of average citation per item and 14th (55) in terms of h-index.