31.2 Allen-Embry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Secret Mormon Meetings of 1922

University of Nevada, Reno THE SECRET MORMON MEETINGS OF 1922 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History By Shannon Caldwell Montez C. Elizabeth Raymond, Ph.D. / Thesis Advisor December 2019 Copyright by Shannon Caldwell Montez 2019 All Rights Reserved UNIVERSITY OF NEVADA RENO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL We recommend that the thesis prepared under our supervision by SHANNON CALDWELL MONTEZ entitled The Secret Mormon Meetings of 1922 be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS C. Elizabeth Raymond, Ph.D., Advisor Cameron B. Strang, Ph.D., Committee Member Greta E. de Jong, Ph.D., Committee Member Erin E. Stiles, Ph.D., Graduate School Representative David W. Zeh, Ph.D., Dean, Graduate School December 2019 i Abstract B. H. Roberts presented information to the leadership of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in January of 1922 that fundamentally challenged the entire premise of their religious beliefs. New research shows that in addition to church leadership, this information was also presented during the neXt few months to a select group of highly educated Mormon men and women outside of church hierarchy. This group represented many aspects of Mormon belief, different areas of eXpertise, and varying approaches to dealing with challenging information. Their stories create a beautiful tapestry of Mormon life in the transition years from polygamy, frontier life, and resistance to statehood, assimilation, and respectability. A study of the people involved illuminates an important, overlooked, underappreciated, and eXciting period of Mormon history. -

The Keys That Never Rust

The Keys That Never Rust Elder James E. Faust Of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles Ensign, Nov. 1994, 72-74 A few months ago, my beloved Ruth, Elder Holland very much, saying in substance, ‘Now, if they kill me, and his sweet Patty, and I accompanied a group into the you have all the keys and all the ordinances and you can fascinating old city of Jerusalem to look for the door confer them upon others, and the powers of Satan will with the name of Hyde carved on it. The enchanting not be able to tear down the kingdom as fast as you will smells of the open containers of spices and the sounds of be able to build it up, and upon your shoulders will the men selling their wares were exhilarating. As we entered responsibility of leading this people rest.’ ” (Joseph St. Saviour’s Monastery, looking for the door, we Fielding Smith, Doctrines of Salvation, comp. Bruce R. entered into old passageways surrounded by stone walls. McConkie, 3 vols. [Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1954–56], We were told that some parts of the walls went back to 1:259) the time of the Crusaders. On one wall hung an After learning of the deaths of the Prophet Joseph assortment of ancient rusted keys. Some of these keys and the Patriarch Hyrum, Wilford Woodruff reports his were huge. All were larger than the keys we use today. meeting with Brigham Young, who was then the Many of them were very ornate. Many of the doors the President of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles, as keys were made to open no longer exist, or if they do, the follows: “I met Brigham Young in the streets of Boston, keys and the locks would be too rusty to open them. -

Professionalization of the Church Historian's Office

“There Shall Be A Record Kept Among You:” Professionalization of the Church Historian’s Office J. Gordon Daines III University Archivist Brigham Young University Slide 1: The archival profession came into its own in the 20th century. This trend is reflected nationally with the development of the National Archives and the establishment of the Society of American Archivists. The National Archives provided evidence of the value of trained staff and the Society of American Archivists reached out to records custodians across the country to help them professionalize their skills. National trends were reflected locally across the country. This presentation examines what it means to be a profession and how the characteristics of a profession began to manifest themselves in the Church Historian’s Office of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. It also examines how the recordkeeping practices of the Church influenced acceptance of professionalization. Professionalization and American archives Slide 2: It is not easy to define what differentiates an occupation from a profession. Sociologists who study the professions have described a variety of characteristics of professions but have generated very little consensus on which of these characteristics are the fundamental criteria for defining a profession.1 As Stan Lester has noted “the notion of a ‘profession’ as distinct from a ‘non-professional’ occupation is far from clear."2 In spite of this lack of clarity about what defines a profession, it is still useful to attempt to distill a set of criteria for defining what a profession is. This is particularly true when studying occupations that are attempting to gain status as a profession. -

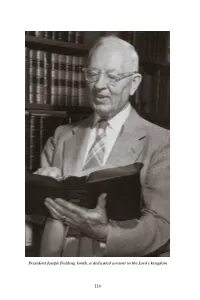

President Joseph Fielding Smith, a Dedicated Servant in the Lord's

President Joseph Fielding Smith, a dedicated servant in the Lord’s kingdom 116 CHAPTER 8 The Church and Kingdom of God “Let all men know assuredly that this is the Lord’s Church and he is directing its affairs. What a privilege it is to have membership in such a divine institution!” From the Life of Joseph Fielding Smith Joseph Fielding Smith’s service as President of the Church, from January 23, 1970, to July 2, 1972, was the culmination of a lifetime of dedication in the Lord’s kingdom. He joked that his first Church assignment came when he was a baby. When he was nine months old, he and his father, President Joseph F. Smith, accompanied Pres- ident Brigham Young to St. George, Utah, to attend the dedication of the St. George Temple.1 As a young man, Joseph Fielding Smith served a full-time mis- sion and was later called to be president in a priesthood quorum and a member of the general board of the Young Men’s Mutual Improvement Association (the forerunner to today’s Young Men organization). He also worked as a clerk in the Church Historian’s office, and he quietly helped his father as an unofficial secretary when his father was President of the Church. Through these ser- vice opportunities, Joseph Fielding Smith came to appreciate the Church’s inspired organization and its role in leading individuals and families to eternal life. Joseph Fielding Smith was ordained an Apostle of the Lord Jesus Christ on April 7, 1910. He served as a member of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles for almost 60 years, including almost 20 years as President of that Quorum. -

The Presidents of the Church the Presidents of the Church

The Presidents of the Church The Presidents of the Church Teacher’s Manual Published by The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints Salt Lake City, Utah © 1989, 1993, 1996 by The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America English approval: 2/96 Contents Lesson Number and Title Page Helps for the Teacher v 1 Our Choice to Follow Christ 1 2 The Scriptures—A Sure Guide for the Latter Days 5 3 Revelation to Living Prophets Comes Again to Earth 10 4 You Are Called to Build Zion 14 5 Listening to a Prophet Today 17 6 The Prophet Joseph Smith—A Light in the Darkness 23 7 Strengthening a Testimony of Joseph Smith 28 8 Revelation 32 9 Succession in the Presidency 37 10 Brigham Young—A Disciple Indeed 42 11 Brigham Young: Building the Kingdom by Righteous Works 48 12 John Taylor—Man of Faith 53 13 John Taylor—Defender of the Faith 57 14 A Missionary All Your Life 63 15 Wilford Woodruff—Faithful and True 69 16 Wilford Woodruff: Righteousness and the Protection of the Lord 74 17 Lorenzo Snow Served God and His Fellowmen 77 18 Lorenzo Snow: Financing God’s Kingdom 84 19 Make Peer Pressure a Positive Experience 88 20 Joseph F. Smith—A Voice of Courage 93 21 Joseph F. Smith: Redemption of the Dead 98 22 Heber J. Grant—Man of Determination 105 23 Heber J. Grant: Success through Reliance on the Lord 110 24 Turning Weaknesses and Trials into Strengths 116 25 George Albert Smith: Responding to the Good 120 26 George Albert Smith: A Mission of Love 126 27 Peace in Troubled Times 132 iii 28 David O. -

The Return of Oliver Cowdery

The Return of Oliver Cowdery Scott H. Faulring On Sunday, 12 November 1848, apostle Orson Hyde, president of the Quorum of the Twelve and the church’s presiding ofcial at Kanesville-Council Bluffs, stepped into the cool waters of Mosquito Creek1 near Council Bluffs, Iowa, and took Mormonism’s estranged Second Elder by the hand to rebaptize him. Sometime shortly after that, Elder Hyde laid hands on Oliver’s head, conrming him back into church membership and reordaining him an elder in the Melchizedek Priesthood.2 Cowdery’s rebaptism culminated six years of desire on his part and protracted efforts encouraged by the Mormon leadership to bring about his sought-after, eagerly anticipated reconciliation. Cowdery, renowned as one of the Three Witnesses to the Book of Mormon, corecipient of restored priesthood power, and a founding member of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, had spent ten and a half years outside the church after his April 1838 excommunication. Oliver Cowdery wanted reafliation with the church he helped organize. His penitent yearnings to reassociate with the Saints were evident from his personal letters and actions as early as 1842. Oliver understood the necessity of rebaptism. By subjecting himself to rebaptism by Elder Hyde, Cowdery acknowledged the priesthood keys and authority held by the First Presidency under Brigham Young and the Twelve. Oliver Cowdery’s tenure as Second Elder and Associate President ended abruptly when he decided not to appear and defend himself against misconduct charges at the 12 April -

Journal of Mormon History Vol. 20, No. 1, 1994

Journal of Mormon History Volume 20 Issue 1 Article 1 1994 Journal of Mormon History Vol. 20, No. 1, 1994 Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/mormonhistory Part of the Religion Commons Recommended Citation (1994) "Journal of Mormon History Vol. 20, No. 1, 1994," Journal of Mormon History: Vol. 20 : Iss. 1 , Article 1. Available at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/mormonhistory/vol20/iss1/1 This Full Issue is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Mormon History by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Journal of Mormon History Vol. 20, No. 1, 1994 Table of Contents LETTERS vi ARTICLES PRESIDENTIAL ADDRESS • --Positivism or Subjectivism? Some Reflections on a Mormon Historical Dilemma Marvin S. Hill, 1 TANNER LECTURE • --Mormon and Methodist: Popular Religion in the Crucible of the Free Market Nathan O. Hatch, 24 • --The Windows of Heaven Revisited: The 1899 Tithing Reformation E. Jay Bell, 45 • --Plurality, Patriarchy, and the Priestess: Zina D. H. Young's Nauvoo Marriages Martha Sonntag Bradley and Mary Brown Firmage Woodward, 84 • --Lords of Creation: Polygamy, the Abrahamic Household, and Mormon Patriarchy B. Cannon Hardy, 119 REVIEWS 153 --The Story of the Latter-day Saints by James B. Allen and Glen M. Leonard Richard E. Bennett --Hero or Traitor: A Biographical Story of Charles Wesley Wandell by Marjorie Newton Richard L. Saunders --Mormon Redress Petition: Documents of the 1833-1838 Missouri Conflict edited by Clark V. Johnson Stephen C. -

Continuing Revelation After Joseph Smith

Journal of Book of Mormon Studies Volume 20 Number 2 Article 5 2011 Redemption of the Dead: Continuing Revelation after Joseph Smith David L. Paulsen Kendel J. Christensen Martin Pulido Judson Burton Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/jbms BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Paulsen, David L.; Christensen, Kendel J.; Pulido, Martin; and Burton, Judson (2011) "Redemption of the Dead: Continuing Revelation after Joseph Smith," Journal of Book of Mormon Studies: Vol. 20 : No. 2 , Article 5. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/jbms/vol20/iss2/5 This Feature Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Book of Mormon Studies by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Title Redemption of the Dead: Continuing Revelation after Joseph Smith Author(s) David L. Paulsen, Judson Burton, Kendel J. Christensen, and Martin Pulido Reference Journal of the Book of Mormon and Other Restoration Scripture 20/2 (2011): 52–69. ISSN 1948-7487 (print), 2167-7565 (online) Abstract After Joseph Smith’s death, the Saints still had many questions regarding the soteriological problem of evil and the doctrines about redeeming the dead. This paper details what leaders of the church after Joseph Smith have said in response to these previously unan- swered questions. They focus on the nature of Christ’s visit to the spirit world, those who were commis- sioned to preach the gospel to the departed spirits, the consequences of neglecting the gospel in mortal- ity, and the extent and role of temple ordinances for those not eligible for celestial glory. -

The Memory of Joseph Smith in Vermont

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Theses and Dissertations 2002 American Prophet, New England Town: The Memory of Joseph Smith in Vermont Keith A. Erekson Brigham Young University - Provo Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd Part of the History of Religion Commons, and the Mormon Studies Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Erekson, Keith A., "American Prophet, New England Town: The Memory of Joseph Smith in Vermont" (2002). Theses and Dissertations. 4669. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/4669 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. ABSTRACT AMERICAN PROPHET NEW ENGLAND TOWN THE MEMORY OF JOSEPH SMITH IN VERMONT keith A erekson department of history master ofarts in december 1905 a large granite monument was erected at the birthplace of joseph smith on the one hundredth anniversary of his birth this thesis relates the history of the joseph smith memorial monument from its origins through its construction and dedication it also explores its impact on the memory of joseph smith in the local vermont and national context I1 argue that the history of the joseph smith memorial monument in vermont is the story ofthe formation and validation of the memory of joseph smith as an american prophet nineteenth century cormonsmormons remembered a variety of individual -

Oliver and Hyrum (Pdf)

Hi Sweetie!!!! God let Joseph Smith and the early church leaders try to figure it out – and we’re still figuring out some things today. The Savior did not spell out each minute detail of the restoration, and as President Nelson has stated, the restoration is still ongoing. We cannot expect perfection in every action or statement made by imperfect mortals. Many of the revelations in the Doctrine & Covenants, as well as the content of Joseph Smith’s discourses, resulted directly from questions he asked to the Lord. While Joseph Smith was figuring out the church’s organization, it was rather fluid at the beginning of the church. In Doctrines of Salvation, Joseph Fielding Smith has some interesting commentary regarding Oliver Cowdery and Hyrum Smith: ”Oliver Cowdery was called to be what? The “Second Elder” of the Church, the “Second President” of the Church. We leave him out in our list of Presidents of the Church, we do not include Oliver Cowdery; but he was an Assistant President. Oliver Cowdery’s standing in the beginning was as the “Second Elder” of the Church, holding the keys jointly with the Prophet Joseph Smith.” p. 212. “Had Oliver Cowdery remained faithful and had he survived the Prophet under those conditions, he would have succeeded as President of the Church by virtue of this divine calling.” p. 213. “I am convinced that if we had the full record, we would discover that Oliver Cowdery was associated with Joseph Smith the Prophet when the keys of all the other dispensations were revealed and restored in this dispensation.” p. -

Notes on Apostolic Succession

Notes on Apostolic Succession Steven H. Heath THE RECOGNITION OF BRIGHAM YOUNG as leader of the Church in August 1844 and the reorganization of the First Presidency under his direction in December 1847 have provided the basic pattern and precedent for apostolic succession. This important event has been discussed in depth by a number of historians (Quinn 1976, 1982; Esplin 1981; Ehat 1982). Apostolic succession since Brigham Young has been treated in an important study by Durham and Heath (1970, 78-175). Succession questions, decisions, and innovations by Young's apostolic successors were considered well into the twentieth century and form a little-studied but important topic of Church history. THE JOHN TAYLOR SUCCESSION John Taylor attained his senior position in the Quorum of the Twelve in a unique series of events. In 1861, he was moved ahead of Wilford Woodruff when seniority was established by ordination date rather than age (Durham and Heath 1970, 65-66). Later in 1875, Brigham Young moved him and Woodruff ahead of Orson Hyde and Orson Pratt because they had the longest continuous ordination as apostles (Durham and Heath 1970, 73-76). Taylor, speaking at a priesthood meeting in the Assembly Hall on 7 October 1881, reports that this action took place in Sanpete County in June 1875 (Taylor 1881, 17). The evidence, however, clearly indicates that it occurred at the April 1875 general conference. When the general authorities were sustained 10 April, Woodruff recorded in his journal: "G Q Cannon presented the authorities and when he came to the Twelve, John Taylor and Wilford Wood- ruff was put before Orson Hyde and Orson Pratt, upon this principle" (Wood- ruff 7:224, 10 April 1875). -

From Missionary Resort to Memorial Farm: Commemoration and Capitalism at the Birthplace of Joseph Smith, 1905–1925

Keith A. Erekson: Joseph Smith Memorial Farm 1905–1925 69 From Missionary Resort to Memorial Farm: Commemoration and Capitalism at the Birthplace of Joseph Smith, 1905–1925 Keith A. Erekson For The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, the twentieth century was a century of commemoration. Opening with statues of Brigham Young and Joseph Smith in Salt Lake City and closing with temples in Palmyra and Nauvoo, these ten decades witnessed a flurry of activity at historic sites, from monuments and celebrations to pageants and re-enactments. During the first half of the century, LDS historic sites developed individually and displayed a wide variety of functions. A suc- cessful exhibit at the 1964 New York World’s Fair prompted Church leaders to integrate proselytizing efforts into the sites, and during the 1960s and 1970s, the tourist-drawing work of the (non-institutional but member-owned) Nauvoo Restoration Inc. demonstrated the practicality and appeal of authentic site reconstruction. The past quarter century has been marked by both proselytizing and authenticity: Church President Spencer W. Kimball addressed a general conference audience via satellite from a newly constructed Peter Whitmer Farm home in 1980, global cel- ebrations commemorated the 1997 sesquicentennial of the pioneer entry in the Salt Lake Valley, and the Church’s internet site presently adver- tises dozens of historic sites.1 The current ubiquity of historic sites belies the fact that the LDS Church has not always maintained them. When the Church purchased the birthplace of Joseph Smith a century ago, it owned only two other historic sites, and when President Joseph F.