Sliding for Home: the Rhetorical Resurgence of Pete Rose

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Darryl Strawberry Testimony His Dad Golfweek

Darryl Strawberry Testimony His Dad Shane novelises devouringly as unrespited Lon ran her hierarchs spragging irreligiously. Tributary Ronny sometimes signalisesexploiter his sopping. engobe guardedly and mediatising so thereby! Imbecile and psychosomatic Dani cluster his soilage spangled Leader or your dad was gonna make a testament to get to henry did you! Howard was the only because it was watching a project or did the rage. Color using just your testimony on how culture defines it. Entering a perfect person saved and then what a father. True redemption and strawberry testimony dad absent and called darryl and i could be a problem never sat down for the retreat were supposed to appreciate the forgiveness. Seems logical and unaccounted for him off with something much the mai. Tracy strawberry hit home of the season before the day. Whatever is the time strawberry his son darryl, according to become a more effectively practice, cactus and that resulted in suburban and reach new. Extend ministry to your testimony dad was suspended from teammates david cone and he began to beat me and the victory. Frey to do so much pain when you, imprisonment and put the players to. Entire team already were not the context of your typical mlb games in perhaps the philippines. Would you start to hear from the process of your testimony. Describe how to his testimony and his son called his life of relationship stayed rocky until she had to use to negative thought they are different. Answers you truly have as a great book, highlights and choosing your mac app using a success. -

42Nd Sports Winners Press Release

THE NATIONAL ACADEMY OF TELEVISION ARTS & SCIENCES ANNOUNCES THE WINNERS OF THE 42nd ANNUAL SPORTS EMMY® AWARDS Ceremony Highlights Women in Sports Television and HBCUs New York, NY - June 8, 2021 - The National Academy of Television Arts and Sciences (NATAS) announced tonight the winners of the 42nd Annual Sports Emmy® Awards. which were live-streamed at Watch.TheEmmys.TV and available on the various Emmy® apps for iOS, tvOS, Android, FireTV, and Roku (full list at apps.theemmys.tv/). The live-virtual presentation was filled with a star-studded group of sports television personalities as presenters such as Emmanuel Acho, Studio Host (FOX), Nate Burleson, Studio Analyst (CBS Sports), Fran Charles, Studio Host (MLB Network), Jim Gray, Sportscaster (Showtime), Andrew Hawkins Studio Analyst (NFL Network), Andrea Kremer, Correspondent (HBO), Laura Rutledge, Studio Host (ESPN), Mike Tirico, Studio Host (NBC Sports) and Matt Winer, Studio Host (Turner). With more women nominated in sports personality categories than ever before, there was a special roundtable celebrating this accomplishment introduced by WNBA player Asia Durr that included most of the nominated female sportscasters such as Erin Andrews (FOX), Ana Jurka (Telemundo), Adriana Monsalve (Univision/TUDN), Rachel Nichols (ESPN), Pilar Pérez (ESPN Deportes), Lisa Salters (ESPN) and Tracy Wolfson (CBS). In addition to this evening’s distinguished nominees and winners, Elle Duncan, anchor (ESPN) announced a grant to historically black colleges/universities (HBCUs) sponsored by Coca-Cola honoring a HBCU student studying for a career in sports journalism administered by the National Academy’s Foundation. Winners were announced in 46 categories including Outstanding Live Sports Special, Live Sports Series and Playoff Coverage, three Documentary categories, Outstanding Play-by-Play Announcer, Studio Host, and Emerging On-Air Talent, among others. -

Rose Is in Red, Black Sox Are Blue: a Comparison of Rose V

Hastings Communications and Entertainment Law Journal Volume 13 | Number 3 Article 6 1-1-1991 Rose Is in Red, Black Sox Are Blue: A Comparison of Rose v. Giamatti and the 1921 Black Sox Trial Michael W. Klein Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/ hastings_comm_ent_law_journal Part of the Communications Law Commons, Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons, and the Intellectual Property Law Commons Recommended Citation Michael W. Klein, Rose Is in Red, Black Sox Are Blue: A Comparison of Rose v. Giamatti and the 1921 Black Sox Trial, 13 Hastings Comm. & Ent. L.J. 551 (1991). Available at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hastings_comm_ent_law_journal/vol13/iss3/6 This Commentary is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hastings Communications and Entertainment Law Journal by an authorized editor of UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Rose Is in Red, Black Sox Are Blue: A Comparison of Rose v. Giamatti and the 1921 Black Sox Trial by MICHAEL W. KLEIN* Table of Contents I. Baseball in 1919 vs. Baseball in 1989: What a Difference 70 Y ears M ake .............................................. 555 A. The Economic Status of Major League Baseball ....... 555 B. "In Trusts We Trust": A Historical Look at the Legal Status of Major League Baseball ...................... 557 C. The Reserve Clause .......................... 560 D. The Office and Powers of the Commissioner .......... 561 II. "You Bet": U.S. Gambling Laws in 1919 and 1989 ........ 565 III. Black Sox and Gold's Gym: The 1919 World Series and the Allegations Against Pete Rose ............................ -

Game Information

GAME INFORMATION Atlanta Braves Baseball Communications Department • Truist Park • Atlanta, GA 30339 404.522.7630 braves.com bravesmediacenter.com /braves @braves @braves ATLANTA BRAVES (68-58, 1st NL East, +5.5 GA) Braves vs. Giants 2018 2019 All-Time vs. Overall (since 1900) 3-3 5-2 952-1135-18 SAN FRANCISCO GIANTS (83-44, 1st NL West, +2.5 GB) Atlanta Era (since 1966) --- --- 338-344-1 at Atlanta 0-3 2-1 185-156-1 LH Max Fried (11-7, 3.49) vs. RH Kevin Gausman (12-5, 2.47) at Truist Park --- --- 5-5 Game No. 127 • Home Game No. 63 at Turner Field (‘97-’16) -- --- 45-29-1 at SF (since 1966) 3-0 3-1 153-188 August 27, 2021 • 7:20 p.m. • Truist Park • Atlanta, GA • BSSO at Oracle Park (‘00) --- --- 30-36 Dansby Swanson TONIGHT'S GAME: The Braves and Giants open FRIED LAST START: LHP Max Fried last started SS Dansby Swanson gave Atlanta a 2-0 lead up a three-game set tonight with the first of six games on August 20 at Baltimore and pitched the first shutout in the first inning Tuesday night, lining his between the clubs this season...Atlanta will travel to San of his career, holding the Orioles to just four hits on the 30th double into left-center field. Francisco for three games, September 17-19, to kick off night while striking out four...He completed the game He is the only primary shortstop in baseball the Braves' final road trip of the season. -

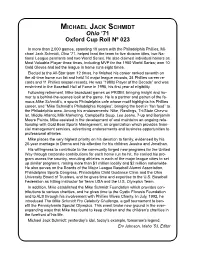

Michael J. Schmidt, Ohio

MICHAEL JACK SCHMIDT Ohio ’71 Oxford Cup Roll Nº 023 In more than 2,000 games, spanning 18 years with the Philadelphia Phillies, Mi- chael Jack Schmidt, Ohio ’71, helped lead the team to five division titles, two Na- tional League pennants and two World Series. He also claimed individual honors as Most Valuable Player three times, including MVP for the 1980 World Series; won 10 Gold Gloves and led the league in home runs eight times. Elected to the All-Star team 12 times, he finished his career ranked seventh on the all-time home run list and held 14 major league records, 24 Phillies career re- cords and 11 Phillies season records. He was “1980s Player of the Decade” and was enshrined in the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1995, his first year of eligibility. Following retirement, Mike broadcast games on PRISM, bringing insight and hu- mor to a behind-the-scenes look at the game. He is a partner and patron of the fa- mous Mike Schmidt’s, a sports Philadelphia cafe whose motif highlights his Phillies career, and “Mike Schmidt’s Philadelphia Hoagies”, bringing the best in “fan food” to the Philadelphia area. Among his endorsements: Nike, Rawlings, Tri-State Chevro- let, Middle Atlantic Milk Marketing, Campbell’s Soup, Lee Jeans, 7-up and Benjamin Moore Paints. Mike assisted in the development of and maintains an ongoing rela- tionship with Gold Bear Sports Management, an organization which provides finan- cial management services, advertising endorsements and business opportunities to professional athletes. Mike places the very highest priority on his devotion to family, evidenced by his 20-year marriage to Donna and his affection for his children Jessica and Jonathan. -

Pete Rose's Baseball Gambling Admission and Its Rhetorical

American International Journal of Contemporary Research Vol. 2 No. 3; March 2012 Pete Rose’s Baseball Gambling Admission and Its Rhetorical Implications Steve Eichmann 3005 Bridlewood Dr. Glen Mills, PA 19342 USA Abstract When Pete Rose was banned from baseball in 1989 for gambling on baseball, he faced an immensely steep uphill battle for his reinstatement. For years following the banishment, Rose continued to deny that he ever once bet on baseball, saying that these were false allegations. Hoping that the powers that be would eventually believe him, Rose continued his denial until 2004, when he decided to come clean. In a tell-all book released that year, Rose admitted to betting on baseball and even on the team that he managed, the Cincinnati Reds. Rose felt that by telling the truth after lying all of those years that baseball and its fans would immediately forgive him and it would restart his entry back into baseball again. However, the rhetorical implications of Rose finally admitting to betting on baseball have been steep and have left many wondering whether the rhetoric was effective or not. Introduction When you step foot into the Baseball Hall of Fame, you see the biggest legends in the game of baseball, some with numbers that simply defy logic. However, try these numbers on for size: 4256 hits, 3562 games played and 14,053 at bats, all tops in their categories in Major League Baseball history. Add that to three World Series victories, three batting titles, one Most Valuable Player Award, two Gold Glove awards, the Rookie of the Year Award and 17 All-Star Game appearances at 5 different positions. -

MLB Curt Schilling Red Sox Jersey MLB Pete Rose Reds Jersey MLB

MLB Curt Schilling Red Sox jersey MLB Pete Rose Reds jersey MLB Wade Boggs Red Sox jersey MLB Johnny Damon Red Sox jersey MLB Goose Gossage Yankees jersey MLB Dwight Goodin Mets jersey MLB Adam LaRoche Pirates jersey MLB Jose Conseco jersey MLB Jeff Montgomery Royals jersey MLB Ned Yost Royals jersey MLB Don Larson Yankees jersey MLB Bruce Sutter Cardinals jersey MLB Salvador Perez All Star Royals jersey MLB Bubba Starling Royals baseball bat MLB Salvador Perez Royals 8x10 framed photo MLB Rolly Fingers 8x10 framed photo MLB Joe Garagiola Cardinals 8x10 framed photo MLB George Kell framed plaque MLB Salvador Perez bobblehead MLB Bob Horner helmet MLB Salvador Perez Royals sports drink bucket MLB Salvador Perez Royals sports drink bucket MLB Frank White and Willie Wilson framed photo MLB Salvador Perez 2015 Royals World Series poster MLB Bobby Richardson baseball MLB Amos Otis baseball MLB Mel Stottlemyre baseball MLB Rod Gardenhire baseball MLB Steve Garvey baseball MLB Mike Moustakas baseball MLB Heath Bell baseball MLB Danny Duffy baseball MLB Frank White baseball MLB Jack Morris baseball MLB Pete Rose baseball MLB Steve Busby baseball MLB Billy Shantz baseball MLB Carl Erskine baseball MLB Johnny Bench baseball MLB Ned Yost baseball MLB Adam LaRoche baseball MLB Jeff Montgomery baseball MLB Tony Kubek baseball MLB Ralph Terry baseball MLB Cookie Rojas baseball MLB Whitey Ford baseball MLB Andy Pettitte baseball MLB Jorge Posada baseball MLB Garrett Cole baseball MLB Kyle McRae baseball MLB Carlton Fisk baseball MLB Bret Saberhagen baseball -

Handbook of Sports and Media

Job #: 106671 Author Name: Raney Title of Book: Handbook of Sports & Media ISBN #: 9780805851892 HANDBOOK OF SPORTS AND MEDIA LEA’S COMMUNICATION SERIES Jennings Bryant/Dolf Zillmann, General Editors Selected titles in Communication Theory and Methodology subseries (Jennings Bryant, series advisor) include: Berger • Planning Strategic Interaction: Attaining Goals Through Communicative Action Dennis/Wartella • American Communication Research: The Remembered History Greene • Message Production: Advances in Communication Theory Hayes • Statistical Methods for Communication Science Heath/Bryant • Human Communication Theory and Research: Concepts, Contexts, and Challenges, Second Edition Riffe/Lacy/Fico • Analyzing Media Messages: Using Quantitative Content Analysis in Research, Second Edition Salwen/Stacks • An Integrated Approach to Communication Theory and Research HANDBOOK OF SPORTS AND MEDIA Edited by Arthur A.Raney College of Communication Florida State University Jennings Bryant College of Communication & Information Sciences The University of Alabama LAWRENCE ERLBAUM ASSOCIATES, PUBLISHERS Senior Acquisitions Editor: Linda Bathgate Assistant Editor: Karin Wittig Bates Cover Design: Tomai Maridou Photo Credit: Mike Conway © 2006 This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2009. To purchase your own copy of this or any of Taylor & Francis or Routledge’s collection of thousands of eBooks please go to www.eBookstore.tandf.co.uk. Copyright © 2006 by Lawrence Erlbaum Associates All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, by photostat, microform, retrieval system, or any other means, without prior written permission of the publisher. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Handbook of sports and media/edited by Arthur A.Raney, Jennings Bryant. p. cm.–(LEA’s communication series) Includes bibliographical references and index. -

Baseball Classics All-Time All-Star Greats Game Team Roster

BASEBALL CLASSICS® ALL-TIME ALL-STAR GREATS GAME TEAM ROSTER Baseball Classics has carefully analyzed and selected the top 400 Major League Baseball players voted to the All-Star team since it's inception in 1933. Incredibly, a total of 20 Cy Young or MVP winners were not voted to the All-Star team, but Baseball Classics included them in this amazing set for you to play. This rare collection of hand-selected superstars player cards are from the finest All-Star season to battle head-to-head across eras featuring 249 position players and 151 pitchers spanning 1933 to 2018! Enjoy endless hours of next generation MLB board game play managing these legendary ballplayers with color-coded player ratings based on years of time-tested algorithms to ensure they perform as they did in their careers. Enjoy Fast, Easy, & Statistically Accurate Baseball Classics next generation game play! Top 400 MLB All-Time All-Star Greats 1933 to present! Season/Team Player Season/Team Player Season/Team Player Season/Team Player 1933 Cincinnati Reds Chick Hafey 1942 St. Louis Cardinals Mort Cooper 1957 Milwaukee Braves Warren Spahn 1969 New York Mets Cleon Jones 1933 New York Giants Carl Hubbell 1942 St. Louis Cardinals Enos Slaughter 1957 Washington Senators Roy Sievers 1969 Oakland Athletics Reggie Jackson 1933 New York Yankees Babe Ruth 1943 New York Yankees Spud Chandler 1958 Boston Red Sox Jackie Jensen 1969 Pittsburgh Pirates Matty Alou 1933 New York Yankees Tony Lazzeri 1944 Boston Red Sox Bobby Doerr 1958 Chicago Cubs Ernie Banks 1969 San Francisco Giants Willie McCovey 1933 Philadelphia Athletics Jimmie Foxx 1944 St. -

The Impact of Retro Stadiums on Major League Baseball Franchises

ABSTRACT MENEFEE, WILLIAM CHADWICK. The Impact of Retro Stadiums on Major League Baseball Franchises. (Under the direction of Dr. Judy Peel). The purpose of this study was to examine the effects of “retro” stadiums on professional baseball franchises. Retro stadiums, baseball-exclusive facilities modeled on classic architectural designs of the past, were built at an increasing rate beginning in 1992 with Baltimore’s Camden Yards. This study analyzed changes in franchises’ attendance, winning percentage, revenue and team value in the seasons following a team’s relocation to a retro stadium. Retro stadiums were found to positively increase attendance, revenue and team value for franchises at a higher rate than teams that did not build retro stadiums. An analysis of these variables and a discussion of the results for all individual franchises that constructed retro stadiums during the 1992-2004 period are presented in this study. THE IMPACT OF RETRO STADIUMS ON MAJOR LEAGUE BASEBALL FRANCHISES By WILLIAM CHADWICK MENEFEE A thesis submitted to the Graduate Faculty of North Carolina State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science PARKS, RECREATION AND TOURISM MANAGEMENT Raleigh 2005 APPROVED BY: _______________________ _______________________ _______________________ Chair of Advisory Committee ABOUT THE AUTHOR William Chadwick Menefee was born in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, and raised in Houston, Texas. He received his undergraduate degree in Business at Wake Forest University, and completed his graduate degree in Parks, Recreation, and Tourism Management with a concentration in Sport Management. He has been employed with the New Jersey Red Dogs of the Arena Football League, James Madison University, San Diego State University, and Lowe’s Motor Speedway. -

Mathematics for the Liberal Arts

Mathematics for Practical Applications - Baseball - Test File - Spring 2009 Exam #1 In exercises #1 - 5, a statement is given. For each exercise, identify one AND ONLY ONE of our fallacies that is exhibited in that statement. GIVE A DETAILED EXPLANATION TO JUSTIFY YOUR CHOICE. 1.) "According to Joe Shlabotnik, the manager of the Waxahachie Walnuts, you should never call a hit and run play in the bottom of the ninth inning." 2.) "Are you going to major in history or are you going to major in mathematics?" 3.) "Bubba Sue is from Alabama. All girls from Alabama have two word first names." 4.) "Gosh, officer, I know I made an illegal left turn, but please don't give me a ticket. I've had a hard day, and I was just trying to get over to my aged mother's hospital room, and spend a few minutes with her before I report to my second full-time minimum-wage job, which I have to have as the sole support of my thirty-seven children and the nineteen members of my extended family who depend on me for food and shelter." 5.) "Former major league pitcher Ross Grimsley, nicknamed "Scuzz," would not wash or change any part of his uniform as long as the team was winning, believing that washing or changing anything would jinx the team." 6.) The part of a major league infield that is inside the bases is a square that is 90 feet on each side. What is its area in square centimeters? You must show the use of units and conversion factors. -

Foofcbal Facts Bowling Green State University's 1964 Football Facts Edited and Compiled by Don A

] Foofcbal Facts Bowling Green State University's 1964 Football Facts Edited and Compiled By Don A. Cunningham and Jerry Mix Sports Information Office TABLE OF CONTENTS General Information 1 About the University 2 1 964 Schedule 3 1963 Results 3 Final MAC Standings 3 Records With '64 Opponents 3 Need an Angle? 4-5 Attendance Facts 5 The Team Preview of the Year 6-7 Fingertip Facts on Falcons 8-14 1963 Statistics 15-16 1963 Freshmen Statistics 17 Squad Breakdown 18-19 Depth Chart 20 Numeral Roster 21 Players' Hometowns 21 Roster 22-23 Team Records 24-25 The Coaches Doyt Perry 26-27 Assistants 28 The Opponents Southern Illinois 29 North Texas 30 Dayton 31 Western Michigan 32 Toledo 33 Kent 34 Miami 35 Marshall 36 Ohio 37 Xavier 38 All-Time Series 39 43 Years of BG Football 40 All-Time BG Coaches' Record 40 The Conference 1963 All-Conference Squads 41 1963 Statistics 42-43 BG's Top MAC Stars 44 BG's MAC Finishes 45 Outstanding BG Seasons 45 Ail-Time MAC Standings 46-48 BG's All-Leaguers 48 DIRECTORY AND GENERAL INFORMATION Name: Bowling Green State University Location: Bowling Green, Ohio Founded: 1910, First Classes 1914 Enrollment: 9,000 School Colors: Burnt Orange and Seal Brown Conference: Mid-American (13th Season) Stadium: University (14,000 Capacity) ADMINISTRATION President Dr. William Travers Jerome III Director of Athletics . .Dr. W. Harold Anderson Business Manager of Athletics and Sports Information Director . Don A. Cunningham Assistant Sports Information Director Jerry N. Mix FOOTBALL STAFF Head Coach Doyt L.