Patterns of Pollen Dispersal in a Small Population of the Canarian Endemic Palm (Phoenix Canariensis)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SZENT ISTVÁN EGYETEM Kertészettudományi Kar

SZENT ISTVÁN EGYETEM Kertészettudományi Kar SORBUS FAJKELETKEZÉS TRIPARENTÁLIS HIBRIDIZÁCIÓVAL A KELET- ÉS DÉLKELET- EURÓPAI TÉRSÉGBEN (Nothosubgenus Triparens) Doktori (PhD) értekezés Németh Csaba BUDAPEST 2019 A doktori iskola megnevezése: Kertészettudományi Doktori Iskola tudományága: Növénytermesztési és kertészeti tudományok vezetője: Zámboriné Dr. Németh Éva egyetemi tanár, DSc Szent István Egyetem, Kertészettudományi Kar, Gyógy- és Aromanövények Tanszék Témavezető: Dr. Höhn Mária egyetemi docens, CSc Szent István Egyetem, Kertészettudományi Kar, Növénytani Tanszék és Soroksári Botanikus Kert A jelölt a Szent István Egyetem Doktori Szabályzatában előírt valamennyi feltételnek eleget tett, az értekezés műhelyvitájában elhangzott észrevételeket és javaslatokat az értekezés átdolgozásakor figyelembe vette, azért az értekezés védési eljárásra bocsátható. .................................................. .................................................. Az iskolavezető jóváhagyása A témavezető jóváhagyása 2 Édesanyám emlékének. 3 4 TARTALOMJEGYZÉK RÖVIDÍTÉSEK JEGYZÉKE .......................................................................................................... 7 1. BEVEZETÉS ÉS CÉLKITŰZÉS .................................................................................................. 9 2. IRODALMI ÁTTEKINTÉS ..................................................................................................... 11 2.1. A Sorbus nemzetség taxonómiai vonatkozásai .................................................................... -

Sorbus Torminalis

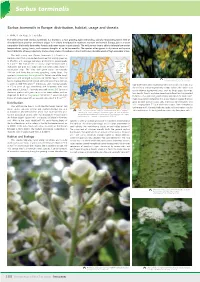

Sorbus torminalis Sorbus torminalis in Europe: distribution, habitat, usage and threats E. Welk, D. de Rigo, G. Caudullo The wild service tree (Sorbus torminalis (L.) Crantz) is a fast-growing, light-demanding, clonally resprouting forest tree of disturbed forest patches and forest edges. It is widely distributed in southern, western and central Europe, but is a weak competitor that rarely dominates forests and never occurs in pure stands. The wild service tree is able to tolerate low winter temperatures, spring frosts, and summer droughts of up to two months. The species often grows in dry-warm and sparse forest habitats of low productivity and on steep slopes. It produces a hard and heavy, durable wood of high economic value. The wild service tree (Sorbus torminalis (L.) Crantz) is a medium-sized, fast-growing deciduous tree that usually grows up to 15-25 m with average diameters of 0.6-0.9 m, exceptionally Frequency 1-3 < 25% to 1.4 m . The mature tree is usually single-stemmed with a 25% - 50% distinctive ash-grey and scaly bark that often peels away in 50% - 75% > 75% rectangular strips. The shiny dark green leaves are typically Chorology 10x7 cm and have five to nine spreading, acute lobes. This Native species is monoecious hermaphrodite, flowers are white, insect pollinated, and arranged in corymbs of 20-30 flowers. The tree Yellow and red-brown leaves in autumn. has an average life span of around 100-200 years; the maximum (Copyright Ashley Basil, www.flickr.com: CC-BY) 1-3 is given as 300-400 years . -

06 087 23 Sorbus.Pdf

414 LXXXVII. ROSACEAE – MALOIDEAE 23. Sorbus HÍBRIDOS C. azarolus × C. monogyna C. × sinaica Boiss., Diagn. Pl. Orient. ser. 2, 2: 48 (1856), pro sp. C. laevigata × C. monogyna C. × media Bechst. in Diana 1: 88 (1797) [n.v.] Mespilus oxyacantha var. laciniata Wallr., Sched. Crit. 1: 219 (1822), nom. illeg., non var. lacinia- ta Desv. (1818) 23. Sorbus L.* [Sórbus, -i f. – lat. sorbus(sorvus), -i f. = principalmente el serbal común –Sorbus domestica L.– y su madera; y quizá el serbal de cazadores –S. aucuparia L.–, pero también un determinado mos- tajo –S. torminalis (L.) Crantz–, cuyo fruto llamó Plinio sorvum torminale] Árboles o arbustos, inermes. Ramas jóvenes con numerosas lenticelas; corte- za gris, lisa o escamosa; yemas cónico-ovoides, ovoides u obovoides, pelosas, ciliadas o glabras, a veces viscosas. Hojas simples o imparipinnadas, caducas, pecioladas; limbo de margen aserrado, dentado o ± lobado; estípulas lineares, lanceoladas o falcadas, ± dentadas, poco visibles, caducas. Inflorescencias cimo- sas, generalmente corimbiformes, en el extremo de ramillas hojosas laterales (braquiblastos), de ramas muy pelosas en la floración y en general casi glabras en la fructificación. Receptáculo campanulado (hipanto), acrescente. Sépalos 5, triangulares, más cortos que los pétalos, marcescentes. Pétalos 5, erectos o pa- tentes, de orbiculares a estrechamente obovados, blancos, rosados o rojos. Estambres 15-20, en 3 verticilos, el externo de c. 10 y los 2 internos de c. 5; an- teras de color blanco, crema o salmón. Carpelos 2-5, encerrados en el receptácu- lo, ± soldados entre sí y con el receptáculo; estilos 2-5, libres o ± soldados entre sí; rudimentos seminales 2 por carpelo, colaterales –al menos en las especies ibé- ricas–. -

New Taxa of Sorbus from Bohemia (Czech Republic)

Verh.© Zool.-Bot. Zool.-Bot. Ges. Österreich, Ges. Austria;Österreich download 133 unter www.biologiezentrum.at(1996): 319-345 New taxa of Sorbus from Bohemia (Czech Republic) M iloslav Ko v a n da Three species of Sorbus are described as new: S. rhodanthera (one Station in W Bohemia) and S. gemella (one Station in W Central Bohemia) belonging to the S. latifolia agg. and S. quernea (two stations in Central Bohemia) of the S. hybrida agg. Basic data on their karyology, morphology, Variation, relation- ships, geographical distribution, ecology and ecobiology are provided. Also described is one primary hybrid, S. X abscondita (S. aucuparia L. X S. danu- bialis [JÄv.] P rodan) o f the S. hybrida agg. Kovanda M., 1996: Neue Sorbus-Taxa aus Böhmen (Tschechische Republik). Drei Sorbus- Arten werden als neu beschrieben: S. rhodanthera (ein Fundort in W-Böhmen) und S. gemella (ein Fundort in W-Mittelböhmen) der S. latifolia agg. und S. quernea (zwei Fundorte in Mittelböhmen) der S. hybrida agg. Grundlegende Daten zur Karyologie, Morphologie, Variation, Verwandtschaft, geographischen Verbreitung, Ökologie, Phytozönologie und Ökobiologie werden präsentiert. Weiters wird eine Primärhybride, S. X abscondita (S. aucuparia L. X S. danubialis [JÄv.] Prodan) der 5. hybrida agg. beschrieben. Keywords: Sorbus, Bohemia, chromosome numbers, morphological Variation, geographical distribution, ecology, phytocenology, ecobiology, interspecific hybridization. Introduction Interspecific hybridization with concomitant polyploidy and apomixis is an acknowledged vehicle of speciation in Sorbus (e.g. Liu efo r s 1953, 1955, Ko v a n d a 1961, Challice & Ko v a n d a 1978, Ja nk un & Ko v a n da 1986, 1987, 1988, Kutzelnigg 1994). -

In Vitro Investigation of Sorbus Domestica As an Enzyme Inhibitor

Istanbul J Pharm 50 (1): 28-32 DOI: 10.26650/IstanbulJPharm.2019.0071 Original Article In vitro investigation of Sorbus domestica as an enzyme inhibitor Gozde Hasbal1 , Tugba Yilmaz-Ozden1 , Musa Sen2, Refiye Yanardag2 , Ayse Can1 1Istanbul University, Faculty of Pharmacy, Department of Biochemistry, Istanbul, Turkey 2Istanbul University Cerrahpaşa, Cerrahpaşa Faculty of Engineering, Department of Chemistry, Istanbul, Turkey ORCID IDs of the authors: G.H. 0000-0002-0216-7635; T.Y.Ö. 0000-0003-4426-4502; R.Y. 0000-0003-4185-4363; A.C. 0000-0002-8538-663X Cite this article as: Hasbal, G., Yilmaz-Ozden, T., Sen, M., Yanardag, R., & Can, A. (2020). In vitro investigation of Sorbus domestica as an enzyme inhibitor. İstanbul Journal of Pharmacy, 50(1), 28–32. ABSTRACT Background and Aims: Finding new therapeutic enzyme inhibitors by investigating especially medicinal plants is an impor- tant research area. The fruits and leaves of Sorbus domestica (service tree) are used as food and folk remedies due to astrin- gent, antidiabetic, diuretic, antiinflammatory, antiatherogenic, antidiarrhoeal, vasoprotective, and vasorelaxant activities, and also used commercially as a vitamin and antioxidant. In this study, the therapeutic effect of S. domestica against diabetes, Alzheimer’s disease, aging, and hyperuricemia was investigated. Methods: α-Glucosidase, α-amylase, acetylcholinesterase (AChE), butyrylcholinesterase (BChE), elastase and xanthine oxidase (XO) inhibitory activities of the fruit extract from S. domestica were measured. Results: The extract showed inhibitory activity against α-glucosidase, α-amylase, BChE, elastase, and XO whereas AChE inhibitory activity of the extract could not be determined. Moreover, the inhibition effects of the extract against α-glucosidase and elastase were more effective than the standard drugs acarbose and ursolic acid, respectively. -

Sorbus Torminalis Present of Vascular Plants Isles (1992)

Article Type: Biological Flora BIOLOGICAL FLORA OF THE BRITISH ISLES* No. 286 List Vasc. Pl. Br. Isles (1992) no. 75, 28, 24 Biological Flora of the British Isles: Sorbus torminalis Peter A. Thomas† School of Life Sciences, Keele University, Staffordshire ST5 5BG, UK Running head: Sorbus torminalis Article †Correspondence author. Email: [email protected] * Nomenclature of vascular plants follows Stace (2010) and, for non-British species, Flora Europaea. Summary 1. This account presents information on all aspects of the biology of Sorbus torminalis (L.) Crantz (Wild Service-tree) that are relevant to understanding its ecological characteristics and behaviour. The main topics are presented within the standard framework of the Biological Flora of the British Isles: distribution, habitat, communities, responses to biotic factors, responses to environment, structure and physiology, phenology, floral and seed characters, herbivores and disease, history, and conservation. 2. Sorbus torminalis is an uncommon, mostly small tree (but can reach 33 m) native to lowland England and Wales, and temperate and Mediterranean regions of mainland Europe. It is the most shade-tolerant member of the genus in the British Isles and as a result it is more closely associated with woodland than any other British species. Like other British Sorbus species, however, it grows best where competition for space and sunlight is limited. Seedlings are shade tolerant but adults are only moderately so. This, combined with its low competitive ability, restricts the best growth to open areas. In shade, saplings and young adults form a sapling bank, This article has been accepted for publication and undergone full peer review but has not Accepted been through the copyediting, typesetting, pagination and proofreading process, which may lead to differences between this version and the Version of Record. -

Tree Age Effects on Seed Germination in Sorbus Torminalis

GENTree. A PPLage .effects PL A NT on P HYSIOLOseed germinationG Y , 2007, in 33Sorbus (1-2), torminalis 107-119 107 TREE AGE EFFECTS ON SEED GERMINATION IN SORBUS TORMINALIS K. Espahbodi1, S. M. Hosseini2*, H. Mirzaie–Nodoushan3, M. Tabari2 , M. Akbarinia2, Y. Dehghan-Shooraki4 1Natural Resources Faculty, Tarbiat Modares University, Noor, Mazandarn, Iran and Agriculture and Natural Resources Research Center of Mazandaran province 2Natural Resources Faculty, Tarbiat Modares University, Noor, Mazandarn, Iran 3Seed and Plant Certification and Registration Institute, Karaj, Iran 4Scientific board member of Forests and Rangelands Research Institute, Tehran, Iran Received 27 October 2006 Summary. Wild service tree (Sorbus torminalis) is a valuable native species in Iran. It is one of the best alternative species for plantation in Hyrcanian forest in Northern Iran. In order to determine tree age effects on seed germination in a mountainous nursery, seeds were collected from 40 individual trees on nearly 40000 hectares of Iranian residual forests (1700-2200 m altitude) and planted during 2 successive years in a nursery, located 1500 m above sea level. Percentage of germinated seeds was recorded for the two planting dates. Age effects (DBH) on seed germination rate were significant (p<0.05). The best germination rate was related to trees with DBH of 25 to 35 cm both in the first and second year. Besides, differences between total germination rate during the first and second years were significant (p<0.01). Seed germination measured in the first year increased by 9.22% compared with the second year. The _____________ *Corresponding author, email: [email protected] and [email protected] 108 K. -

Variability of Morphological and Biological Characteristics of Wild Service Tree (Sorbus Torminalis (L.) Crantz) Fruits and Seeds from Different Altitudes

PERIODICUM BIOLOGORUM UDC 57:61 VOL. 111, No 4, 495–504, 2009 CODEN PDBIAD ISSN 0031-5362 Original scientific paper Variability of morphological and biological characteristics of Wild Service Tree (Sorbus torminalis (L.) Crantz) fruits and seeds from different altitudes Abstract MILAN OR[ANI]1 DAMIR DRVODELI]1 Aims and objectives of research: The study aimed to research the influ- TOMISLAV JEMRI]2 ence of altitude on dimensions, i.e. the shape of Wild Service tree fruits IGOR ANI]1 1 (Sorbus torminalis (L.) Crantz). We also wanted to test the variability of STJEPAN MIKAC major biological characteristics of fruits and seed, the elements of seed qual- 1 University of Zagreb ity and their relations. Faculty of Forestry Materials and Methods: In September 2003 we gathered fruits from 24 Department of Ecology and Silviculture Wild Service Trees of different ages and positions in the stand structure on P. P. 4 2 2 HR – 10002 Zagreb, Croatia three sites (Medvednica, Psunj and Ju`ni Dilj) situated at different alti- tudes. The altitude of each tree was determined with the GPSmap 60CSx 2 University of Zagreb device, after which dendrometric measurements were carried out and fruits Faculty of Agriculture were collected. We measured fruit length (FL) and width (FW) and calcu- Department of Pomology lated their index (FL/FW). The mass of each fruit was weighed on the labo- Sveto{imunska 25 HR – 10000 Zagreb, Croatia ratory scales Sartorius and the number of fruits per kilo was calculated. The seeds were manually extracted from the fruits and the number of filled Correspondence: (sound) seeds per fruit was counted in line with the ISTA rules. -

Sorbus Torminalis

Technical guidelines for genetic conservation and use Wild service tree Sorbus torminalis B. Demesure-Musch and S. Oddou-Muratorio EUFORGEN INRA, Genetic Conservation of Forest Trees ONF, Olivet, France These Technical Guidelines are intended to assist those who cherish the valuable wild service tree genepool and its inheritance, through conserving valuable seed sources or use in practical forestry. The focus is on conserving the genetic diversity of the species at the European scale. The recommendations provided in this module should be regarded as a commonly agreed basis to be complemented and further developed in local, national or regional conditions. The Guidelines are based on the available knowledge of the species and on widely accepted methods for the conservation of forest genetic resources. Biology and ecology Wild service tree (Sorbus tormi- nalis L. (Crantz)) is a diploid species (2n=34) belonging to the family Rosaceae. It can hybridize with at least two other species of Sorbus: whitebeam (Sorbus aria) and mountain ash (Sorbus aucu- paria). Hybridization with white- beam commonly occurs, especially where the natural ranges of these species over- lap. Most of these hybrids are triploid (3n=51) and a few (mainly Sorbus latifolia) are tetraploid (4n=78). Hybrids reproduce mainly by apomixes. Wild service tree is a fast- growing tree, reaching maximum height at around 80–100 years, when they are typically 20–25 m in height with trunks of 50–70 cm diameter. Exceptional trees can reach up to 30 m in height and 1 m diameter at 200 years old. Wild service tree produces hermaphrodite flowers visited by a wide range of generalist polli- nators (social bees, bumblebees orbusSorbus torminalisWild service treeSorbus torminalistorminalisWild service treeSorbus torminalisWild s and beetles). -

"III. Rózsa- És Galagonya-Kutatás a Kárpát-Medencében"

„III. RÓZSA- ÉS GALAGONYA-KUTATÁS A KÁRPÁT-MEDENCÉBEN” NEMZETKÖZI KONFERENCIA 2019. JÚNIUS 1. BUDATÉTÉNYI RÓZSAKERT, BUDAPEST, MAGYARORSZÁG KONFERENCIA-KÖTET – PROCEEDINGS-BOOK „3RD ROSE- AND HAWTHORNRESEARCH IN CARPATHIAN BASIN” INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE 1ST JUNE 2019. ROSARIUM OF BUDATÉTÉNY, BUDAPEST, HUNGARY „III. RÓZSA- ÉS GALAGONYA-KUTATÁS A KÁRPÁT-MEDENCÉBEN” NEMZETKÖZI KONFERENCIA 2019. JÚNIUS 1. BUDATÉTÉNYI RÓZSAKERT, BUDAPEST, MAGYARORSZÁG KONFERENCIA-KÖTET „3RD ROSE- AND HAWTHORNRESEARCH IN CARPATHIAN BASIN” INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE 1ST JUNE 2019. ROSARIUM OF BUDATÉTÉNY, BUDAPEST, HUNGARY PROCEEDINGS-BOOK 1 Konferencia-kötet szerkesztők (Editors of Proceedings-book): KERÉNYI-NAGY VIKTOR – GYURICZA CSABA – ESTÓK JÁNOS – PALKOVICS LÁSZLÓ – LAKATOS TAMÁS – BÉRES ANDRÁS Borító (Cover photo): Rosa hungarica A. KERNER, Budaörs (fotó: Kerényi-Nagy Viktor) Kiadja (Published by): Szent István Egyetemi Kiadó Készült (Print run): 100 példányban A kiadvány a Szent István Egyetem támogatásával készült. (The proceedings book was sponsorated by Szent István University) ISBN 978-963-7092-87-9 2 A KONFERENCIA (THE CONFERENCE) Szervező- és tudományos bizottsága (Professional and scienticfic support): Dr. GYURICZA CSABA, Nemzeti Agrárkutatási és Innovációs Központ, főigazgató Dr. LAKATOS TAMÁS, NAIK-Gyümölcstermesztési Kutatóintézet intézetigazgató Dr. PREININGER ÉVA, NAIK-GyKI kutatási igazgatóhelyettes Dr. ESTÓK JÁNOS, Magyar Mezőgazdasági Múzeum és Könyvtár főigazgató Dr. KERÉNYI-NAGY VIKTOR, MMgMK, muzeológus DR. PALKOVICS LÁSZLÓ, Szent István -

Co-Rrelation of Fruit Size with Morpho-Physiological Properties

Correlation of Fruit Size with Morphophysiological Properties and Germination Rate of the Seeds of ServiceISSN Tree (Sorbus 1847-6481 domestica L.) eISSN 1849-0891 ORiGinal SCienTiFiC PaPeR DOI: https://doi.org/10.15177/seefor.18-01 Correlation of Fruit Size with Morphophysiological Properties and Germination Rate of the Seeds of Service Tree (Sorbus domestica L.) 1 1 2 2,3 2 Damir Drvodelić , Milan Oršanić , Marko Vuković , Mushtaque ahmed Jatoi , Tomislav Jemrić * (1) University of Zagreb, Faculty of Forestry, Department of Forest Ecology and Silviculture, Citation: DRVODELIĆ D, ORŠANIĆ M, Svetošimunska 25, HR-10000 Zagreb, Croatia; (2) University of Zagreb, Faculty of Agriculture, VUKOVIĆ M, JATOI MA, JEMRIĆ T 2018 Department of Pomology, Svetošimunska 25, HR-10000 Zagreb, Croatia; (3) Shah Abdul Latif Co-rrelation of Fruit Size with Morpho- University, Date Palm Research Institute, 66020, Khairpur, Pakistan physiological Properties and Germination Rate of the Seeds of Service Tree (Sorbus * Correspondence: e-mail: [email protected] domestica L.). South-east Eur for 9 (1): 47-54. DOI: https://doi.org/10.15177/ seefor.18-01 Received: 26 Nov 2017; Revised: 16 Jan 2018; accepted: 26 Jan 2018; Published online: 12 Feb 2018 abstract background and Purpose: The current study aims to evaluate the effect of the fruit size of service tree (Sorbus domestica L.) on physio-morphological properties of seeds and the seed germination process. Materials and Methods: The fruit samples varying in size and divided on the basis of weight into small (5-10 g), medium (11-15 g) and large (16-20 g) were collected from the area of Vukomeričke gorice (45°34′45″N 16°00′11″E), Zagreb County, Croatia. -

ECOLOGY and DISTRIBUTION of SERVICE TREE Sorbus Domestica (L.) in SLOVAKIA

Ekológia (Bratislava) Vol. 27, No. 2, p. 152–167, 2008 ECOLOGY AND DISTRIBUTION OF SERVICE TREE Sorbus domestica (L.) IN SLOVAKIA VIERA PAGANOVÁ Faculty of Horticulture and Landscape Engineering, Slovak Agricultural University, Tulipánová 7, 949 01 Nitra, Slovak Republic; e-mail: [email protected] Abstract Paganová V.: Ecology and distribution of service tree Sorbus domestica (L.) in Slovakia. Ekológia (Bratislava), Vol. 27, No. 2, p. 152–167, 2008. Service tree Sorbus domestica L. is one of the rare autochthonous woody plants. There are analysed data from 24 localities with service tree in Slovakia. They were found mainly in agricultural land (242 individuals) and just on 5 forest stands (22 individuals). Service tree stands were found on south-east, south and south-west exposures. More than 90% of them were on altitudes up to 400 m. The majority of the stands were found in the subtype of mostly warm plain climate, as well as in the subtypes of warm and moderate warm fold climate and mountain climate. In our country service tree grows on soils with favourable physical characteristics and adsorbing complex. The soils are fertile, well supplied with nutrients (Luvisols, Cambisols) on 96% of analysed stands. Some localities (4%) have soils rich in minerals, but the soil chemistry is one-sided, so they are mostly little fertile (Rendzinas). Regarding the water content in soils generally, Cambisols have sufficient water-supply. The Luvisols have lower water supply with possibility of their aridization. Rendzinas are mostly loose soils with good permeability, regarding their shallow profile with lower water capacity and good drainage of the parent rock they have usually less water supply.