1 Why Media Researchers Don't Care About Teletext

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Readers' Guide Retrospective: 1890-1982 (H.W

Readers' Guide Retrospective: 1890-1982 (H.W. Wilson) Peer- ISSN Publication Name Publisher Indexing Start Indexing Stop Reviewed 0163-2027 50 Plus 50 Plus 1978/09 1982/12 0568-0727 Aerospace Technology 1967/07 1968/06 0002-0966 Aging Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office 1968/01 1982/04 0364-4006 ALA Bulletin American Library Association 1961/01 1969/12 0002-7049 America America Press Inc. 1953/03 1982/12 0002-7375 American Artist Aspire Media, Interweave Press, Inc. 1953/01 1982/12 0271-5767 American Catholic Quarterly Review 1900/01 1912/12 American Child 1919/05 1922/08 0002-7936 American City 1909/01 1974/12 0149-337X American City & County Penton Media, Inc. 1975/01 1977/12 American City (Town and County edition) 1914/01 1920/06 0194-8008 American Craft American Craft Council 1979/06 1983/01 American Economic Association Bulletin 1911/04 1911/04 0002-8282 American Economic Review American Economic Review 1911/01 1912/12 Y 0002-8304 American Education Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office 1964/12 1982/11 0002-8541 American Forests American Forestry Association 1953/01 1977/12 0002-8738 American Heritage American Heritage Publishing 1952/09 1982/12 American Historical Association. Reports 1898/00 1922/00 0002-8762 American Historical Review American Historical Assn. 1895/10 1977/12 Y 0002-8770 American History Illustrated American History Illustrated 1974/02 1982/12 0002-8789 American Home 1928/12 1977/12 1049-1104 American Homes and Gardens 1909/01 1915/08 0065-860X American Imago Johns -

Loudoun County Public Schools

LOUDOUN COUNTY PUBLIC SCHOOLS DEPARTMENT OF BUSINESS & FINANCIAL SERVICES PROCUREMENT AND RISK MANGEMENT DIVISION 21000 Education Court, Suite #301 Ashburn, VA 20148 Phone (571) 252-1270 Fax (571) 252-1432 July 1, 2021 Contract Information Title: Magazine and Periodical Subscription Service IFB/RFP Number: IFB #I21332 Supersedes: IFB #I17142 Vendor Name: Debarment Form: Required: No Form on File: Not Applicable Contractor Certification: Required: No Form on File: Not Applicable Virginia Code 22.1-296.1 …the school board shall require the contractor to provide certification that all persons who will provide such services have not been convicted of a felony or any offense involving the sexual molestation or physical or sexual abuse or rape of a child. Pricing: See attached Pricing Sheet(s) Contract Period: July 1, 2021 – June 30, 2022 Contract Renewal New Number: Number of Renewals 4 Remaining: Procurement Contact: Pixie Calderwood Procurement Director: Andrea Philyaw LOUDOUN COUNTY PUBLIC SCHOOLS DEPARTMENT OF BUSINESS & FINANCIAL SERVICES PROCUREMENT AND RISK MANAGEMENT SERVICES 21000 Education Court, Suite #301 Ashburn, VA 20148 Phone (571) 252-1270 Fax (571) 252-1432 June 28, 2021 NOTICE OF AWARD IFB #I21332 Magazine and Periodical Subscription Services Loudoun County Public Schools is awarding IFB #I21332 Magazine and Periodical Subscription Services to EBSCO Information Services of Birmingham, AL. We appreciate your interest in being of service to the Loudoun County Public Schools. Andrea Philyaw Procurement Director LOUDOUN COUNTY PUBLIC SCHOOLS IFB #I21332 MAGAZINES AND PERIODICALS SUBSCRIPTION SERVICE Package 1: Library Office Print & Online Line Awarded UoM Title Name Format Publisher Name ISSN # Item Price 1EAComputers in Libraries Print Information Today, Inc. -

BONNIER ANNUAL REPORT Table of Contents

BONNIERS ÅRSBERÄTTELSE 2017 1 2018BONNIER ANNUAL REPORT Table of Contents Board of Directors’ Report 3 Consolidated Income Statements 14 Consolidated Statements of Comprehensive Income 14 Consolidated Statements of Financial Position 15 Consolidated Statements of Changes in Equity 17 Consolidated Statements of Cash Flow 18 Notes to the Consolidated Financial Statements 19 The Parent Company’s Income Statements 48 The Parent Company’s Statements of Comprehensive Income 48 The Parent Company’s Balance Sheets 49 The Parent Company’s Statements of Changes in Equity 50 The Parent Company’s Statements of Cash Flow 50 Notes to the Parent Company’s Financial Statements 51 Auditor’s Report 61 Multi-year Summary 63 Translation from the Swedish original bonnier ab annual report 2018 2 Board of Directors’ Report The Board of Directors and the CEO of Bonnier AB, corporate Development of the operations, financial position and registration no. 556508-3663, herewith submit the annual report profit or loss (Group) and consolidated financial statements for the 2018 financial year on pages 3-60. SEK million (unless stated otherwise) 2018 2017 2016 Net sales 26,447 25,740 25,492 The Group’s business area and business model EBITA1) 824 625 731 Bonnier AB is a parent company in a media group with companies in Operating profit/loss -225 -1,423 630 3) TV, daily newspapers, business media, magazines, film production, Net financial items -157 -212 -239 books, e-commerce and digital media and services. The group con- Profit/loss before tax -382 -1,635 391 3) ducts operations in 12 countries with its base in the Nordic countries Profit/loss for the year -872 -2,239 276 3) and significant operations in the United States, Germany, United EBITA margin 3.1% 2.4% 2.9% Kingdom and Eastern Europe. -

Loudoun County Public Schools Ifb I21332 Magazine and Periodicals Subscription Service Library Office - Print and Online Package 1

LOUDOUN COUNTY PUBLIC SCHOOLS IFB I21332 MAGAZINE AND PERIODICALS SUBSCRIPTION SERVICE LIBRARY OFFICE - PRINT AND ONLINE PACKAGE 1 Line Quantity UoM Title Name Format Publisher Name ISSN # Item 1 1 EA Computers in Libraries Print Information Today, Inc. 1041-7915 2 1 EA Teacher Librarian Print + Online E L Kurdyla Publishing, LLC 1481-1782 LOUDOUN COUNTY PUBLIC SCHOOLS IFB I21332 MAGAZINE AND PERIODICALS SUBSCRIPTION SERVICE ELEMENTARY SCHOOLS - PRINT AND ONLINE PACKAGE 2 Line Item Quantity UoM Title Name Format Publisher Name ISSN # 1 2 EA Animal Tales Print A360 Media, LLC 2373-8278 2 1 EA Bazoof! Print + Online Dream Wave Publishing, Inc. 2369-6389 3 7 EA Boys Life Print Boys Life 0006-8608 4 4 EA Brainspace Print Brainspace Publishing, Inc. 2291-8930 5 5 EA Catster Print Belvoir Publs, Inc. 2376-8258 6 1 EA Chirp Print Owlkids 1206-4580 7 2 EA ChopChop Magazine Print Chopchop Magazine 2169-0987 8 1 EA Click Print Cricket Media 2694-1171 9 2 EA Cobblestone Print Cricket Media 0199-5197 10 1 EA Discovery Box Print Bayard Presse 1366-9028 11 4 EA Dogster Print Belvoir Publs, Inc. 2376-8266 12 2 EA Faces Print Cricket Media 0749-1387 13 1 EA Girls Life Print Red Engine, LLC 1078-3326 14 1 EA Girls World Print A360 Media, LLC 2332-4511 15 3 EA Highlights for Children Print Highlights For Children 0018-165X 16 1 EA Highlights High Five Print Highlights For Children 1943-1465 17 1 EA Horn Book Magazine Print Library Journals, LLC 0018-5078 18 1 EA ID : Ideas & Discoveries Print Bauer Publishing 2161-2641 Ingredient : A Magazine for Kids -

Country Media Point Media Type

Country Media Point Media Type Austria satzKONTOR Blog Austria A1 Telekom Austria AG Company/Organisation Austria Accedo Austria GmbH Company/Organisation Austria Agentur für Monopolverwaltung Company/Organisation Austria AGES – Agentur für Ernährungssicherheit Company/Organisation Austria AGGM – Austrian Gas Grid Management GmbHCompany/Organisation Austria Agrana AG Company/Organisation Austria Agrarmarkt Austria Company/Organisation Austria AHHV Verlags GmbH Company/Organisation Austria Aidshilfe Salzburg Company/Organisation Austria Air Liquide Company/Organisation Austria AIZ - Agrarisches Informationszentrum Company/Organisation Austria AKH – Allgemeines Krankenhaus der Stadt WienCompany/Organisation Austria Albatros Media GmbH Company/Organisation Austria Albertina Company/Organisation Austria Alcatel Lucent Austria AG Company/Organisation Austria Allgemeine Baugesellschaft A. Porr AG Company/Organisation Austria Allianz Elementar Versicherungs-AG Company/Organisation Austria Alphaaffairs Kommunikationsberatung Company/Organisation Austria Alpine Bau Company/Organisation Austria Alstom Power Austria AG Company/Organisation Austria AMA - Agrarmarkt Austria Marketing Company/Organisation Austria Amnesty International Company/Organisation Austria AMS Arbeitsmarktservice – BundesgeschäftsstelleCompany/Organisation Austria AMS Burgenland Company/Organisation Austria AMS Kärnten Company/Organisation Austria AMS Niederösterreich Company/Organisation Austria AMS Oberösterreich Company/Organisation Austria AMS Salzburg Company/Organisation -

The Future of Education, Including the Importance of the Affective

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 197 074 CE 027 573 AUTHOR Spitze, Hazel Taylor, Ed. TITLE Proceedings of the Conference on Current Concerns in Home Economics Education (Champaign, Illinois, April 16-19, 1973). INSTITUTION Illinois Univ., Urbana. Dept. of Vocational and Technical Education. PUB DATE Apr. 78 NOTE 73p. AVAILABLE FROM Illinois Teacher, College of Education, University of Illinois, 1310 S. 6th St., Champaign, IL 61820 ($2.00: $1.00, 100 or more copies). EDRS PRICE MF01/PC01 Plus Postage. DESCPIPTO"RS *Educational Needs: Educational Objectives; Educational Philosophy: *Educational Planning: Futures (of Society): *Home Economics; *Home Economics Education: Legislation; *Policy Formation: Postsecondary Education: Professional Associations: Professional Development: Professional Education; Professional Recognition: Reputation; Secondary Education: *Social Problems: Status IDENTIFIERS *Social Impact: *Societal Needs ABSTRACT Participants in a conference held in April, 1978, had four main objectives: (1) to help identify and become more aware of the current concerns in home economics education: (2) to value the role of home economics education in promoting needed social change: (3) to contribute during the conference to the generation of possible solutions and actions to be taken regaIding current social problems; and (4) to make plans and feel committed to share the conference with others in their home state or region. To accomplish these objectives, speakers, beggining with keynote speaker Marjorie East, focused on issues such as the profession of home economics and how to build it: the future of education, including the importance of the affective domain, the accountability movement, and the National Institute of Education evaluation of consumer and homemaking education; and needs in secondary home economics education programs in the 1980s. -

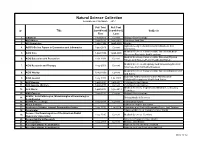

Natural Science Collection Accurate As of 06 March 2017

Natural Science Collection Accurate as of 06 March 2017 Full Text Full Text Lp Title (combined) (combined) Subjects First Last 1. 3 Biotech 1-kwi-2012 Current Biology--Biotechnology 2. A&D Watch 1-sty-2013 1-gru-2015 Petroleum And Gas 3. AEI Newsletter 1-cze-1998 1-paź-2000 Energy Agriculture--Agricultural Economics|Business And 4. AGRIS On-line Papers in Economics and Informatics 1-gru-2010 Current Economics Medical Sciences--Communicable Diseases|Medical 5. AIDS Care 1-paź-1996 1-paź-2000 Sciences--Psychiatry And Neurology Medical Sciences--Communicable Diseases|Physical 6. AIDS Education and Prevention 1-sie-1998 Current Fitness And Hygiene|Public Health And Safety Medical Sciences--Allergology And Immunology|Medical 7. AIDS Research and Therapy 1-sty-2009 Current Sciences--Communicable Diseases Medical Sciences--Communicable Diseases|Public Health 8. AIDS Weekly 13-lut-1995 Current And Safety Business And Economics--Labor And Industrial 9. AIHA Journal 1-sty-1993 1-lis-2003 Relations|Occupational Health And Safety 10. AKC Gazette 1-paź-2001 1-wrz-2011 Pets|Sports And Games 11. AKC Gazette (Online) 1-paź-2011 Current Pets|Sports And Games Medical Sciences--Experimental Medicine, Laboratory 12. ALN World 1-paź-2013 1-gru-2014 Technique 13. AMB Express 1-sty-2012 Current Biology--Biotechnology APMIS ; Acta Pathologica, Microbiologica et Immunologica 14. Biology|Medical Sciences Scandinavica 15. ASTRA Proceedings 1-sty-2014 Current Astronomy|Physics 16. About Campus Education--Higher Education 17. Academica Science Journal, Geographica Series 1-sty-2012 1-lip-2014 Environmental Studies|Geography|Travel And Tourism 18. Accelerator Education|Sciences: Comprehensive Works Access : the Newsmagazine of the American Dental 19. -

Bonnier Annual Review

2019BONNIER ANNUAL REVIEW Albert Bonniers Förlag publishes its first The statue Det Fria book by August Strindberg, Från Fjerdingen Ordet (The Free och Svartbäcken, in 1877. During the 1880s Word) from 1947 by and ’90s, Albert Bonniers Förlag becomes sculptor Puck Stock- the leading publisher of fiction, with lassa has long been authors such August Strindberg, Selma a symbol of Bonni- Lagerlöf, Gustaf Fröding and Verner von er’s core values. A Heidenstam. large version of the statue can be found outside Bonnier- huset on Torsgatan in Stockholm. The characteristic B, designed by Karl-Erik Forsberg for Bonnier in the 1960s, is still a The daily paper symbol for the company. Seen Tidning Avesta here as cufflinks, designed by has been pub- lished since 1882. The In October 2019, silversmith Klara Eriksson. Dagens newspaper covers the industri, southern part of Dalarna as the first busi- ness daily in the world, province. It is included in starts to regularly publish MittMedia, which became climate indicators on the a part of Bonnier News in stock market pages and the spring of 2019. on di.se. By doing so, Di 75 years. Journalism just as sharp now as highlights climate factors in 1944, the year that as decisive business light of day. The first edition of ratios. was printed as World WarExpressen II was raging, on November 16, 1944. The ideas behind saw the Expressen Expressen and Carl-Adam came Nycop, from Albertand set Bonnier the tone. Jr. Expressen Karin Olsson, chief culture editor at currents in society.was founded to offset Nazi gives a speech at a manifestation in supportExpressen of , Swedish-Chinese bookseller Gui Minhai, being detained in China. -

Central & Eastern Europe Market & Mediafact 2009 Edition

Central & Eastern Europe Market & MediaFact 2009 Edition Compiled by: Anne Austin, Nicola Hutcheon Produced by: David Parry © 2010 ZenithOptimedia All rights reserved. This publication is protected by copyright. No part of it may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form, or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without written permission from the copyright owners. ISSN 1469-6622 Every effort has been made in the preparation of this book to ensure accuracy of the contents, but the publishers and copyright owners cannot accept liability in respect of errors or omissions. Readers will appreciate that the data is only as up-to-date as printing schedules will allow and is subject to change. ZENITHOPTIMEDIA ZenithOptimedia is one of the world's leading ZenithOptimedia is committed to delivering to global media services agencies with 218 offices clients the best possible return on their in 72 countries. advertising investment. Key clients include AlcatelLucent, Beam Global This approach is supported by a unique system Spirits & Wine, British Airways, Darden for strategy development and implementation, Restaurants, Electrolux, General Mills, Giorgio The ROI Blueprint. At each stage, proprietary Armani Parfums, Kingfisher, Mars, Nestlé, ZOOM (ZenithOptimedia Optimisation of Media) L'Oréal, Puma, Polo Ralph Lauren, Qantas, tools have been designed to add value and Richemont Group, Sanofi-Aventis, Siemens, insight. Thomson Multimedia, Toyota/Lexus, Verizon, Whirlpool and Wyeth. The ZenithOptimedia -

With Customers in Mind. W

ANNUAL REVIEW 2015. With Customers in Mind. W This is Bonnier. We continuously reinvent media. Bonnier is the Nordic region’s leading media company, with over 200 years of experience in changing media markets. We are based in Sweden, have operations in 15 countries and are wholly owned by the Bonnier family. Our businesses span the media spectrum, with a strong historic core in independent journalism and book publishing. Now we are working to turn Bonnier into a leading digital media group. 2 BONNIER ANNUAL REVIEW 2015 W Contents 4 6 12 Guaranteeing the future. With Customers in Mind. Where Consumers Are ... In 2015, Bonnier showed that we can reach Three companies. Three different Power lies in the hands of consumers as a balance between investing in the future and approaches to growing and developing never before when it comes to digital media. being profitable, says CEO Tomas Franzén. business with a focus on the consumer. What are the trends affecting media? 16 18 20 Books. Broadcasting. Business to Business. It was a stable year of literary and Record digital consumption and continued Record profits made 2015 a great year, commercial success, with new initiatives high linear viewing marked the year. And with a number of major acquisitions such like Type & Tell, with head of business new viewers were reached through projects as Deutsche Wirtschafts Nachrichten, development Rebecka Leffler. like multi-channel network ENT. with Christoph Hermann. 22 24 26 Growth Media. Magazines. News. An intensive year of investments The business area's house & home Earnings improved and digital readership and organic growth included the launch titles in the Nordic region improved increased, with more online subscribers of Kit, with Linda Öhrn Lernström, profitability, with Erik Rimmer and digital ad sales than ever, head of features. -

Business Wire Catalog

Full Global Comprehensive media coverage in the Americas, including the US (National Circuit), Canada and Latin America, Asia-Pacific, Europe (including saturated coverage of Central and Eastern Europe), Middle East, and Africa. Distribution to a global mobile audience via a variety of platforms and aggregators including AFP Mobile, AP Mobile and Yahoo! Finance. Includes Full Text translations in Arabic, simplified-PRC Chinese & traditional Chinese, Czech, Dutch, French, German, Hebrew, Hungarian, Indonesia (Bahasa), Italian, Japanese, Korean, Malay, Polish, Portuguese, Russian, Slovak, Slovenian, Spanish, Thai, Turkish, and Vietnamese based on your English-language news release. Additional translation services are available. Full Global Der Standard Thomson Reuters OSCE Secretariat All Europe Die Furche Magazines & Periodicals x.news Information Technology Albania Die Presse New Business GMBH Newspapers Heute News.at Belarus 24 Orë Hrvatske Novine Profil Newspapers Albanian Daily News Kleine Zeitung Trend BDG Gazeta 55 Kurier Television Belarus Today Gazeta Ballkan Neue Kronen Zeitung ATV Belarusky Riynok Gazeta Shqip Neue Vorarlberger Tageszeitung ORF Belgazeta Gazeta Shqiptare Neues Volksblatt Radio Television Autrichienne - Gomel'skaya Pravda Integrimi Niederösterreichische APA Minskij Kurier Koha Jone Nachrichten Servus TV Narodnaya Gazeta Metropol Oberösterreichische ServusTV Nasha Niva Panorama Nachrichten Radio Respublika Rilindja Demokratike Gazete Osttiroler Bote Antenne Oesterreich - Radio Telegraf Shekulli Regionalmedien.at -

Business Wire Catalog

Full Global Comprehensive media coverage in the Americas, including the US (National Circuit), Canada and Latin America, Asia-Pacific, Europe (including saturated coverage of Central and Eastern Europe), Middle East, and Africa. Distribution to a global mobile audience via a variety of platforms and aggregators including AP Mobile, Yahoo! Finance and Viigo. Includes Full Text translations in Arabic, simplified- PRC Chinese & traditional Chinese, Czech, Dutch, French, German, Hebrew, Hungarian, Italian, Japanese, Korean, Polish, Portuguese, Russian, Slovak, Slovenian, Spanish, Thai and Turkish based on your English-language news release. Additional translation services are available. Full Global Der Standard Magazines & Periodicals Respublika All Europe Die Furche Format Telegraf Albania Die Presse New Business Vechernie Bobruisk Newspapers Heute News Vyecherny Brest 24 Orë Hrvatske Novine Profil Vyecherny Minsk Albanian Daily News Kleine Zeitung Trend Zviazda Gazeta 55 Kurier Television Zvyazda Gazeta Albania Neue Kronen Zeitung ATV Magazines & Periodicals Gazeta Ballkan Neue Kärntner Tageszeitung ORF Belarus Segodnya Gazeta Shqip Neue Vorarlberger Tageszeitung Radio Online Gazeta Shqiptare Neues Volksblatt Hitradio Ö3 bobr.by Integrimi Niederösterreichische Osterreichischer Rundfunk ORF Chapter 97 Koha Jone Nachrichten Online Computing News Metropol Oberösterreichische Ariva.de TUT.BY Panorama Nachrichten Finanzen.net Belgium Rilindja Demokratike Gazete Osttiroler Bote Finanznachrichten.de Newspapers Shekulli Salzburger Fenster Live-PR