Copyright Protection of Digital Audio Radio Broadcasts: the “Audio Flag”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Proposed Rules Federal Register Vol

32068 Proposed Rules Federal Register Vol. 83, No. 133 Wednesday, July 11, 2018 This section of the FEDERAL REGISTER [email protected]. Each can be annual statements of account with contains notices to the public of the proposed contacted by telephone by calling (202) respect to distribution, accompanied by issuance of rules and regulations. The 707–8350. royalty payments.8 The Register receives purpose of these notices is to give interested SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION: all royalty payments and, after persons an opportunity to participate in the deducting the reasonable costs incurred rule making prior to the adoption of the final I. Background rules. for administering this license, deposits A. The Audio Home Recording Act of the balance with the Treasury of the 1992 and DART Royalty Funds United States.9 These royalty payments LIBRARY OF CONGRESS The Audio Home Recording Act of are divided between a sound recording fund and a musical works fund, which 1992 (AHRA) 1 amended title 17 to are in turn subdivided into various Copyright Office ‘‘provide a legal and administrative subfunds, referred to collectively as the framework within which digital audio DART subfunds.10 The royalty 37 CFR Part 201 recording technology may be made payments attributed to these subfunds available to consumers,’’ 2 including to [Docket No. 2018–6] are allocated to copyright owners implement a royalty payment system pursuant to distribution orders issued in Streamlining the Administration of regarding the importation, manufacture, proceedings before the CRJs, as DART Royalty Accounts and Electronic and distribution of digital audio described in section 1007 and in various Royalty Payment Processes recording devices or media. -

1 United States District Court Southern District of New

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK -----------------------------------X ATLANTIC RECORDING CORPORATION; BMG MUSIC; CAPITOL RECORDS, INC.; ELEKTRA ENTERTAINMENT GROUP, INC.; INTERSCOPE RECORDS; MOTOWN RECORD COMPANY, L.P.; SONY BMG MUSIC ENTERTAINMENT; UMG RECORDINGS, INC.; VIRGIN RECORDS AMERICA, INC.; and WARNER BROS. RECORDS INC., Plaintiffs - against - 06 Civ. 3733 (DAB) MEMORANDUM & ORDER XM SATELLITE RADIO, INC., Defendant. -----------------------------------X DEBORAH A. BATTS, United States District Judge. Above-named Plaintiffs (hereinafter “Plaintiffs” or “the Record Companies”) bring this action against Defendant XM Satellite Radio, Inc. (“XM”). Plaintiffs allege XM operates a digital download subscription service that distributes Plaintiffs’ copyrighted works without their authority. Plaintiffs contend this conduct violates federal and state copyright and unfair competition laws. Now before this Court is XM’s motion to dismiss the Complaint, pursuant to Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 12(b)(6). Plaintiffs bring nine causes of action against Defendant XM. Count One alleges that XM directly infringes on the Record 1 Companies’ exclusive distribution rights, in violation of sections 106(3) and 501 of the Copyright Act of 1976 (“the Copyright Act”). Count Two alleges that XM also violates 17 U.S.C. §§ 115, 501, which bar unauthorized digital phonorecord delivery. In Counts Three and Four, the Record Companies allege XM directly infringes upon their exclusive right to reproduce their copyrighted sound recordings: Count Three charges that this activity violates provisions of the Copyright Act which set forth exclusive reproduction rights for copyright owners, namely 17 U.S.C. §§ 106(1), 501. Count Four charges that XM violates its license, granted under 17 U.S.C. -

The Need for a Digital First Sale Doctrine Amendment to the Copyright Act

THIS VERSION MAY CONTAIN INACCURATE OR INCOMPLETE PAGE NUMBERS. PLEASE CONSULT THE PRINT OR ONLINE DATABASE VERSIONS FOR THE PROPER CITATION INFORMATION. NOTE LET ME SELL MY SONG! THE NEED FOR A DIGITAL FIRST SALE DOCTRINE AMENDMENT TO THE COPYRIGHT ACT Kimberly A. Condoulis* I. INTRODUCTION Suppose I had both the e-books and hard copy books of the Harry Potter series. I legally purchased and owned digital copies1 of the series in addition to hard copies. My sister wanted to read the series after I had finished and I had two choices: I could hand her my hard copies of Harry’s adventures or I could e-mail my e-books to her and delete them off my laptop. She did not pay me to borrow the books, but it would not have made a difference if she did. While these two transactions may seem fundamentally the same, the law sees one as legal and the other as copyright infringement. Although copyright owners generally have an exclusive right to sell or distribute their works,2 the Copyright Act includes an important exception— the first sale doctrine or right of first sale.3 This exception allows owners of a * J.D. candidate, 2016, Boston University School of Law. Thank you to Stacey Dogan for her advice and guidance throughout this writing process, to Melissa Nasson for introducing me to this topic and to Wendy Gordon for encouraging my passion for this topic. Also thank you to those in my support system for their endless encouragement and to the Journal of Science & Technology Law editors for their tireless work on this note. -

MP3 in Y2K: the Audio Home Recording Act and Other Important Copyright Issues for the Year MM

MP3 in Y2K: The Audio Home Recording Act and Other Important Copyright Issues for the Year MM INTRODUCTION "The problem's plain to see, too much technology.. The Copyright Act of 19762 (Act) is remarkably well-equipped to deal with new technological challenges to the music industry in the next century. As the Internet changes the way music is bought, sold and enjoyed in fundamental ways, the Act keeps pace with the needs of copyright holders. The broad categories provided in the Act, combined with its comfort in an uncertain technological future, make the Act a steadying influence in the face of a changing market for online music. The facility with which the Act provides intellectual property protection, however, is not always to be found in other copyright legislation. Some of the statutory amendments to the original Act do not adequately balance the competing interests of intellectual property, and do not provide appropriate support for the acquisition and protection of intellectual property rights. Currently, the best example of these issues is the Audio Home Recording Act (AHRA)3 and the MP3 controversy. This comment will examine the issues and implications of music and the Internet as affected by several competing interests. Part I briefly outlines the current state of affairs in MP3 music by examining the driving forces behind Internet music. Part 1 explains the constitutional rights of copyright holders and the goals of copyright law. The constitutional issues are further developed under the United States Supreme Court's decision in Sony Corp. of America v. Universal City Studios, Inc.4 Part Ill briefly introduces some important aspects of the AHRA. -

Music Piracy and the Audio Home Recording Act

MUSIC PIRACY AND THE AUDIO HOME RECORDING ACT In spite of the guidance provided by the Audio Home Recording Act1 (AHRA) of 1992, music companies are once again at odds with consumer electronics manufacturers. This time around, the dispute is over certain information technology products that enable consumers to copy digital music and transfer them to different formats, or exchange them over the Internet. This article will discuss anti-piracy measures being taken by digital content owners and the United States legislature to combat piracy and evaluate them in light of the AHRA. The Promulgation of Music Piracy Over the last two years, the music industry has fed the media stark statistics about “piracy,” the act of copying digital music content to a blank CD, or uploading or downloading it on the Internet. According to various newspaper articles, an estimated 3.6 billion songs are illegally downloaded each month in the United States.2 In 1999, the music industry estimated that one in four compact discs of new music was actually an unauthorized copy.3 By the end of 2001, it was estimated that as many CDs were burned and copied as were bought.4 In Europe, blank CDs are outselling recorded CDs (although these blank CDs might have also been purchased for legitimate reasons, such as to back-up personal computer files).5 And since 1999, ownership of CD burners has nearly tripled.6 This trend of consumers sharing their music rather than purchasing it may be attributable to many factors, including the slow economy. However, the music industry seems to believe that the most likely culprit in this trend is the rise of digital music,7 i.e., free online file sharing, and the growing popularity of CD burners.8 In an act of self-defense, the largest record companies are developing anti-piracy technology to protect their copyrighted music against the information technology industry’s 1 17 U.S.C. -

Home Audio Taping of Copyrighted Works and the Audio Home Recording Act of 1992: a Critical Analysis Joel L

Hastings Communications and Entertainment Law Journal Volume 16 | Number 2 Article 4 1-1-1993 Home Audio Taping of Copyrighted Works and the Audio Home Recording Act of 1992: A Critical Analysis Joel L. McKuin Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/ hastings_comm_ent_law_journal Part of the Communications Law Commons, Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons, and the Intellectual Property Law Commons Recommended Citation Joel L. McKuin, Home Audio Taping of Copyrighted Works and the Audio Home Recording Act of 1992: A Critical Analysis, 16 Hastings Comm. & Ent. L.J. 311 (1993). Available at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hastings_comm_ent_law_journal/vol16/iss2/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hastings Communications and Entertainment Law Journal by an authorized editor of UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Home Audio Taping of Copyrighted Works and The Audio Home Recording Act of 1992: A Critical Analysis by JOEL L. McKuIN* Table of Contents I. Home Taping: The Problem and its Legal Status ....... 315 A. Constitutional and Statutory Background ........... 315 B. Home Taping or Home "Taking"?: The History of Home Taping's Legal Status ........................ 318 C. New Technologies Sharpen the Home Taping Problem ............................................ 321 1. The DAT Debacle .............................. 321 2. Other New Technologies ........................ 322 II. The Audio Home Recording Act of 1992 (AHRA) ..... 325 A. Serial Copy Management System (SCMS) .......... 325 B. Royalties on Digital Hardware and Media .......... 326 C. Prohibition of Copyright Infringement Actions ..... 328 III. -

Copyright and the Fall Line

Nimmer Galley 7.11 FINAL (Do Not Delete) 7/12/2013 4:49 PM COPYRIGHT AND THE FALL LINE DAVID NIMMER* I. BODY VS. SPIRIT ............................................................................ 810 II. COSMOGONY VS. EVOLUTION ....................................................... 816 A. The Semiconductor Chip Protection Act .......................... 816 B. The Audio Home Recording Act ...................................... 818 C. Sound Recordings and Music Videos ............................... 819 D. The Digital Millennium Copyright Act ............................ 821 E. The Vessel Hull Design Protection Act ............................ 823 III. ESOTERIC VS. EXOTERIC REVELATION ........................................ 826 IV. IDPPPA: THE FASHION BILL ...................................................... 830 EDITOR’S NOTE In March 2012, the Penn Intellectual Property Group hosted a symposium on the topic of Fashion Law at The University of Pennsylvania Law School. Keynote speaker David Nimmer assessed a proposed bill amending the Copyright Act to add protection for fashion designs. While teaching a seminar at Cardozo Law School in January 2013, Professor Nimmer delivered an illustrated lecture on his experience at the symposium and more recent developments with respect to the fashion bill. The following Article is an edited transcript of Professor Nimmer’s lecture and its accompanying graphics. * The author thanks Shyam Balganesh and the Penn Intellectual Property Group for the initial invitation that prompted this lecture, adding -

Chapter 10 • Digital Audio Recording Devices And

Chapter 10 1 Digital Audio Recording Devices and Media section page 1001 Definitions ................................................274 1002 Incorporation of copying controls ..............................276 1003 Obligation to make royalty payments ...........................277 1004 Royalty payments . 278 1005 Deposit of royalty payments and deduction of expenses . 279 1006 Entitlement to royalty payments . 279 1007 Procedures for distributing royalty payments . 281 1008 Prohibition on certain infringement actions ......................282 1009 Civil remedies ..............................................282 1010 Determination of certain disputes . 284 § 1001 Digital Audio Recording Devices and Media subchapter a — defiNitioNs § 1001 · Definitions As used in this chapter, the following terms have the following meanings: (1) A “digital audio copied recording” is a reproduction in a digital re- cording format of a digital musical recording, whether that reproduction is made directly from another digital musical recording or indirectly from a transmission. (2) A “digital audio interface device” is any machine or device that is de- signed specifically to communicate digital audio information and related interface data to a digital audio recording device through a nonprofessional interface. (3) A “digital audio recording device” is any machine or device of a type commonly distributed to individuals for use by individuals, whether or not included with or as part of some other machine or device, the digital record- ing function of which is designed or marketed for the primary purpose of, and that is capable of, making a digital audio copied recording for private use, except for— (A) professional model products, and (B) dictation machines, answering machines, and other audio record- ing equipment that is designed and marketed primarily for the creation of sound recordings resulting from the fixation of nonmusical sounds. -

LIBRARY of CONGRESS U.S. Copyright Office 37 CFR Part 201

This document is scheduled to be published in the Federal Register on 10/15/2018 and available online at https://federalregister.gov/d/2018-22372, and on govinfo.gov LIBRARY OF CONGRESS U.S. Copyright Office 37 CFR Part 201 [Docket No. 2018-6] Streamlining the Administration of DART Royalty Accounts and Electronic Royalty Payment Processes AGENCY: U.S. Copyright Office, Library of Congress. ACTION: Final rule. SUMMARY: The U.S. Copyright Office is establishing a rule to codify its procedures for closing royalty payments accounts under section 1005 of the Copyright Act, and is amending its regulations governing online payment procedures for statutory licensing statements of account to no longer require that payments for these accounts be made in a single lump sum. These changes are intended to improve the efficiency of the Copyright Office’s Licensing Division operations. DATES: Effective [INSERT DATE 30 DAYS AFTER DATE OF PUBLICATION IN THE FEDERAL REGISTER]. FOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT: Regan A. Smith, General Counsel and Associate Register of Copyrights, by email at [email protected], or Jalyce Mangum, Attorney-Advisor, by email at [email protected]. Each can be contacted by telephone by calling (202) 707-8350. SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION: I. Background On July 11, 2018 (83 FR 32068), the Office published a Notice of Proposed Rulemaking (“NPRM”) to streamline the administration of digital audio recording technology (DART) royalty accounts and the statement of account royalty payment processes. Specifically, the Copyright Office proposed to codify the manner in which it would exercise its statutory authority to close out DART royalty payment accounts under 17 U.S.C. -

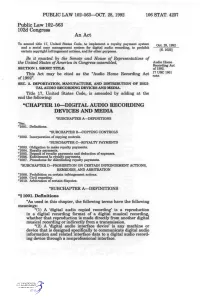

CHAPTER 10—DIGITAL AUDIO RECORDING DEVICES and MEDIA "SUBCHAPTER A—DEFINITIONS "Sec

PUBLIC LAW 102-563—OCT. 28, 1992 106 STAT. 4237 Public Law 102-563 102d Congress An Act To amend title 17, United States Code, to implement a royalty payment system Q^^ 28 1992 and a serial copy management system for digital audio recording, to prohibit certain copyright infringement actions, and for other purposes. "^ •' Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America in Congress assembled. Audio Home Recording Act SECTION 1. SHORT TITLE. of 1992. This Act may be cited as the "Audio Home Recording Act il+Y^ ^^^ of 1992". SEC. 2. IMPORTATION, MANUFACTURE, AND DISTRIBUTION OF DIGI TAL AUDIO RECORDING DEVICES AND MEDIA. Title 17, United States Code, is amended by adding at the end the following: "CHAPTER 10—DIGITAL AUDIO RECORDING DEVICES AND MEDIA "SUBCHAPTER A—DEFINITIONS "Sec. "1001. Definitions. "SUBCHAPTER B—COPYING CONTROLS "1002. Incorporation of copying controls. "SUBCHAPTER C—ROYALTY PAYMENTS "1003. Obligation to make royalty payments. "1004. Royalty payments. "1005. Deposit of royalty payments and deduction of expenses. "1006. Entitlement to royalty pajrments. "1007. Procedures for distributing royalty payments. "SUBCHAPTER D—PROHIBITION ON CERTAIN INFRINGEMENT ACTIONS, REMEDIES, AND ARBITRATION "1008. Prohibition on certain infringement actions. "1009. Civil remedies. "1010. Arbitration of certain disputes. "SUBCHAPTER A—DEFINITIONS *<§ 1001. Definitions "As used in this chapter, the foUovdng terms have the following meanings: "(1) A 'digital audio copied recording* is a reproduction in a digital recording format of a digital musical recording, whether that reproduction is made directly from smother digital musical recording or indirectly from a transmission. "(2) A 'digil^ audio interface device' is any machine or device that is designed specifically to communicate digital audio information and related interface data to a digital audio record ing device through a nonprofessional interface. -

The Audio Home Recording Act of 1992, 1 J

Journal of Intellectual Property Law Volume 1 | Issue 2 Article 5 March 1994 The Audio omeH Recording Act of 1992 Christine C. Carlisle Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.uga.edu/jipl Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, and the Intellectual Property Law Commons Recommended Citation Christine C. Carlisle, The Audio Home Recording Act of 1992, 1 J. Intell. Prop. L. 335 (1994). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.uga.edu/jipl/vol1/iss2/5 This Recent Developments is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ Georgia Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Intellectual Property Law by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Georgia Law. Please share how you have benefited from this access For more information, please contact [email protected]. Carlisle: The Audio Home Recording Act of 1992 RECENT DEVELOPMENTS THE AUDIO HOME RECORDING ACT OF 1992 I. INTRODUCTION The enactment of the Audio Home Recording Act' (AHRA) to regulate the new area of Digital Audio Technology' (DAT) raises several questions in light of the Constitution and the Copyright Act of 1976. This Comment addresses two areas in which problems may exist with the AHRA. First, the AHRA is inconsistent with the Copyright Clause of the Constitution.3 The legislation presents two constitutional concerns: it allows copyright holders to control access to works and it subjects public domain works to copyright protection. Second, the AHRA makes no allowance for the fair use of a copyrighted work under section 107 of the Copyright Act.4 The deficiencies in the AHRA most likely reflect the negotiation process behind the legislation;5 the Act grew out of negotiations and lobbying efforts by special interest groups in the music and electronics industries. -

Subchapter A—Copyright Office and Procedures

SUBCHAPTER A—COPYRIGHT OFFICE AND PROCEDURES PART 201—GENERAL PROVISIONS 201.26 Recordation of documents pertaining to computer shareware and donation of public domain computer software. Sec. 201.27 Initial notice of distribution of dig- 201.1 Communication with the Copyright ital recording devices or media. Office. 201.28 Statements of Account for digital 201.2 Information given by the Copyright audio recording devices or media. Office. 201.29 Access to, and confidentiality of, 201.3 Fees for registration, recordation, and Statements of Account, Verification related services, special services, and Auditor’s Reports, and other verification services performed by the Licensing Di- information filed in the Copyright Office vision. for digital audio recording devices or 201.4 Recordation of transfers and certain media. other documents. 201.5 Corrections and amplifications of 201.30 Verification of Statements of Ac- copyright registrations; applications for count. supplementary registration. 201.31 Procedures for copyright restoration 201.6 Payment and refund of Copyright Of- in the United States for certain motion fice fees. pictures and their contents in accordance 201.7 Cancellation of completed registra- with the North American Free Trade tions. Agreement. 201.8 Disruption of postal or other transpor- 201.32 [Reserved] tation or communication services. 201.33 Procedures for filing Notices of In- 201.9 Recordation of agreements between tent to Enforce a restored copyright copyright owners and public broad- under the Uruguay Round Agreements casting entities. Act. 201.10 Notices of termination of transfers 201.34 Procedures for filing Correction No- and licenses. tices of Intent to Enforce a Copyright 201.11 Satellite carrier statements of ac- Restored under the Uruguay Round count covering statutory licenses for sec- Agreements Act.