Opium Trade in Rajasthan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CRAFT and TRADE in the 18Th CENTURY RAJASTHAN

CRAFT AND TRADE IN THE 18th CENTURY RAJASTHAN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF Boctor of ^l)ilos;opl)p IN )/er HISTORY ! SO I A. // XATHAR HUSSAIN -- .A Under the Supervision of Prof. B. L. Bhadani Chairman & Coordinator CENTRE OF ADVANCED STUDY DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALIGARH (INDIA) 2008 ^Ci>Musu m ABSTRACT The study on the 18* century has been attracting the attention of the historians such as Richard Bamett, C.A. Bayly, Muzaffar Alam, Andre Wink, Chetan Singh and others. Two subsequent works on the eastern Rajasthan by S.P. Gupta and Dilbagh Singh and on the northern Rajasthan by G.S.L. Devra have added new dimensions to the whole issue of existing debate on the 18' century, a period of transition in the history of India. Therefore, the importance of the studies on Rajasthan assumes significance which contains a treasure house of archival records, hitherto largely unexplored. My work is consisted of eight chapters with an introduction and conclusion. The first chapter deals with the study of geographical and historical profile of the Rajasthan. The geographical factor such as types of soils, hills, river and vegetation always nourishes the economy of the region. The physical location of Rajasthan had influenced its history to a greater extent. The region bears the physical diversity and we can divide it into two parts namely in the fertile south eastern zone and the thar arid zone. It was bounded by the Mughal subas (provinces) like Multan, Sindh, Delhi, Agra, Gujarat and Malwa. -

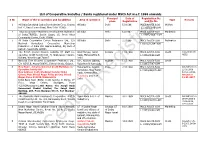

S. No. Regional Office Party/Payee Name Individual

AGRICULTURE INSURANCE COMPANY OF INDIA LTD. STATEMENT OF STALE CHEQUES As on 30.09.2017 Unclaimed amount of Policyholders related to Stale Cheques more than Rs. 1000/- TYPE OF PAYMENT- REGIONAL INDIVIDUAL/ FINANCIAL AMOUNT (IN S. NO. PARTY/PAYEE NAME ADDRESS CLAIMS/ EXCESS SCHEME SEASON OFFICE INSTITUTION RS.) COLLECTION (a) (b) (c) (d) (e) (i) (j) (k) (l) (m) 1 AHMEDABAD BANK OF BARODA, GODHARA FINANCIAL INSTITUTION STATION ROAD ,GODHARA 2110.00 EXCESS COLLECTION NAIS KHARIF 2006 2 AHMEDABAD STATE BANK OF INDIA, NADIAD FINANCIAL INSTITUTION PIJ ROAD,NADIAD 1439.70 EXCESS COLLECTION NAIS KHARIF 2006 3 AHMEDABAD STATE BANK OF INDIA (SBS),JUNAGADH FINANCIAL INSTITUTION CIRCLE CHOWK,JUNAGADH 1056.00 EXCESS COLLECTION NAIS KHARIF 2007 4 AHMEDABAD UNION BANK OF INDIA, NADIAD FINANCIAL INSTITUTION TOWER,DIST.KHEDA,NADIAD 1095.50 EXCESS COLLECTION NAIS KHARIF 2007 5 AHMEDABAD BANK OF BARODA, MEHSANA FINANCIAL INSTITUTION STATION ROAD,MEHSANA 1273.80 EXCESS COLLECTION NAIS KHARIF 2008 PATNAGAR YOJANA 6 AHMEDABAD BANK OF INDIA, GANDHINAGAR FINANCIAL INSTITUTION 13641.60 EXCESS COLLECTION NAIS KHARIF 2008 BHAVAN,GHANDHINAGAR 7 AHMEDABAD ORIENTAL BANK OF COMMERCE, UNJHA FINANCIAL INSTITUTION DIST.MEHSANA,UNJA 16074.00 EXCESS COLLECTION NAIS KHARIF 2008 OTHERS 8 AHMEDABAD NAJABHAI DHARAMSIBHAI SAKARIYA INDIVIDUAL DHANDHALPUR, CHOTILA 1250.00 CLAIMS KHARIF 2009 PRODUCTS OTHERS 9 AHMEDABAD TIGABHAI MAVJIBHAI INDIVIDUAL PALIYALI, TALAJA, BHAVNAGAR 1525.00 CLAIMS KHARIF 2009 PRODUCTS OTHERS 10 AHMEDABAD REMATIBEN JEHARIYABHAI VASAVA INDIVIDUAL SAGBARA, -

20000 Indra Sagar DB Khandwa 15000

MADHYA PRADESH PROJECTS COMMISSIONED Sl no. Name of Type Name of Name of Name of Capacity Head Discharge Remarks COMMISIONED Verified Project State District river/ in in in Date canal kW m m3/sec 1 bargi LBC CB MP 10000 COMMISIONED 2 Bhimgarh DB MP Seoni 2400 10 18 COMMISIONED 1992 3 Birsinghpur CB MP Shahdol 20000 COMMISIONED 1990 4 Birsinghpur MHS CB MP 2200 COMMISIONED 5 Chargaon Jatlapur DB MP Seoni 800 12 8 COMMISIONED 6 Morand CB MP Hoshangabad 1005 3 12 COMMISIONED 2009 7 Satpura CB MP Betul 1000 2 23 COMMISIONED 2009 8 Tawa DB MP Hoshangabad 13500 COMMISIONED 2009 9 Tiwara SHP CB MP Seoni 250 5 7 COMMISIONED 2009 10 Bansagar Tons Ph-4 DB Shahdol 20000 11 Indra sagar DB Khandwa 15000 TOTAL = 86155 AHEC-IITR/SHP Data Base/July 2016 170 MADHYA PRADESH IDENTIFIED FUTURE PROJECTS Sl no. Name of Name of Name of Category Name of Capacity Head Discharge Remarks Annual Project State District of Proj river/ in in in Rainfall * canal kW m m3/sec 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 1 Add MP Sidhi ROR Sone 100 30 1 IPP(Proposed) 1538 2 Amba RD 996 MP Morena Canal Fall Chambal 200 12 Site Identified 1538 3 Asan Fall MP Canal Fall Chambal Lr.C. 2700 13 Site Identified 1050 4 Ataria MP Dam Toe Wainganga 15000 57 Site Identified 5 Bah MP Vidisha ROR 700 30 IPP(Proposed) 6 Bahuti Fall MP Rewa ROR 1500 300 1 IPP 1134 7 Ban Sagar MP ROR Sone 2500 18 Site Identified 1134 8 Bansagar RBC MP Shahdol Canal Fall Bansagar RBC 300 20 3 IPP(Proposed) 776 9 Barna MP Raisen Dam Toe 1500 IPP 835 10 Betwa MP Guna ROR 2000 30 Site Identified 1024 11 Bhawan thadi MP Balaghat -

Teaching Eighteenth-Century French Literature: the Good, the Bad and the Ugly

Eighteenth-Century Modernities: Present Contributions and Potential Future Projects from EC/ASECS (The 2014 EC/ASECS Presidential Address) by Christine Clark-Evans It never occurred to me in my research, writing, and musings that there would be two hit, cable television programs centered in space, time, and mythic cultural metanarrative about 18th-century America, focusing on the 1760s through the 1770s, before the U.S. became the U.S. One program, Sleepy Hollow on the FOX channel (not the 1999 Johnny Depp film) represents a pre- Revolutionary supernatural war drama in which the characters have 21st-century social, moral, and family crises. Added for good measure to several threads very similar to Washington Irving’s “Legend of Sleepy Hollow” story are a ferocious headless horseman, representing all that is evil in the form of a grotesque decapitated man-demon, who is determined to destroy the tall, handsome, newly reawakened Rip-Van-Winkle-like Ichabod Crane and the lethal, FBI-trained, diminutive beauty Lt. Abigail Mills. These last two are soldiers for the politically and spiritually righteous in both worlds, who themselves are fatefully inseparable as the only witnesses/defenders against apocalyptic doom. While the main characters in Sleepy Hollow on television act out their protracted, violent conflict against natural and supernatural forces, they also have their own high production-level, R & B-laced, online music video entitled “Ghost.” The throaty feminine voice rocks back and forth to accompany the deft montage of dramatic and frightening scenes of these talented, beautiful men and these talented, beautiful women, who use as their weapons American patriotism, religious faith, science, and wizardry. -

The Kalinga Collection of Nazarana Coins Auction 41

The Kalinga Collection of Nazarana Coins Auction 41 10 Sep. 2015 | The Diplomat Highlight of Auction 39 63 64 133 111 90 96 97 117 78 103 110 112 138 122 125 142 166 169 Auction 41 The Kalinga Collection of Nazarana Coins (with Proof & OMS Coins) Thursday, 10th September 2015 7.00 pm onwards VIEWING Noble Room Monday 7 Sept. 2015 11:00 am - 6:00 pm The Diplomat Hotel Behind Taj Mahal Palace, Tuesday 8 Sept. 2015 11:00 am - 6:00 pm Opp. Starbucks Coffee, Wednesday 9 Sept. 2015 11:00 am - 6:00 pm Apollo Bunder At Rajgor’s SaleRoom Mumbai 400001 605 Majestic Shopping Centre, Near Church, 144 JSS Road, Opera House, Mumbai 400004 Thursday 10 Sept. 2015 3:00 pm - 6:30 pm At the Diplomat Category LOTS Coins of Mughal Empire 1-75 DELIVERY OF LOTS Coins of Independent Kingdoms 76-80 Delivery of Auction Lots will be done from the Princely States of India 81-202 Mumbai Office of the Rajgor’s. European Powers in India 203-236 BUYING AT RAJGOR’S Republic of India 237-245 For an overview of the process, see the Easy to buy at Rajgor’s Foreign Coins 246-248 CONDITIONS OF SALE Front cover: Lot 111 • Back cover: Lot 166 This auction is subject to Important Notices, Conditions of Sale and to Reserves To download the free Android App on your ONLINE CATALOGUE Android Mobile Phone, View catalogue and leave your bids online at point the QR code reader application on your www.Rajgors.com smart phone at the image on left side. -

Administrative Report on the Census of the Central India Agency, Madhya Pradesh

ADMINISTRATIVE REPORT ON THE CENSUS OF THE CENTRAL INDIA AGENCY, 1921 BY Lieut.-Colonel C. E. LUARD, C.I.E., M.A. (Oxon.), 1.A., Superintendent of Census Operations CALOUTTa SUl'ElUXTENDENT GOVERNMENT PRINTING, INDIA 19;?·~ Agents tor the Sale of Books Published by the Superintendent of Government Printing, India, Calcutta.. OJ EUROPE. COl1:stable & Cn., 10, Or .. n·~c StrJet, L)i'Jester Squa.re, Wneldon & Wesley. Ltd., 2, 3 & 4, Arthur Street, London, W.C. New Oxford Street, London, W. C. 2. Kegan Pa.nl, Tr'cndl, Trnbne" & Co., 68.;4, Carter L"ne, E.C., "au :J\I,New OKlord Street, London, Messrs. E~st and West Ltd.., 3, Victoria St., London, W.C S. W 1. BernMd Quaritch. 11. Gr",fton Stroot, New Bond n. H. Blackwell, GO & 51, Broad SLreet, OxfonJ:. Streot, London, W. Deighton Bell & Co., Ltd., Ca.mbridge. P. S. King & Sons, 2 & 4. Grea.t Smith Street Westminst~r, London, S.W. Oliver & Boyd, Tw"eddalo Ccmrt, Edinburgh. H. S. King & Co .• 65, Cornhill, E.C., and 9, Pal E. Ponsonby, Ltd., l!6, Grafton Stroot, Dublin. Mall, London, W. Ea.rnest Leroux, 28, Rue Bonap"rte, Pal'is. Grindla.v & Co., 54. Parliament Street, London, S.W. Lnzac & Co, 46, Grea.t Hussell Street, London, W.C· MarLinu. Nijhoil', Tho Hague, Holla.nd. W. Thacker & Co., 2, Crew La.no, London, E.C. Otto Harrassowitz" Leipzig. T. }<'isher Unwin, Ltd., No. I, Adelphi Terrace, Friedlander and Sohn, Berlin. London, W.C. IN INDIA AND CEYLON. Thacker, Splllk & Co., Calcutta and Simla. -

UFO Digital Cinema THEATRE COMPANY WEB S.No

UFO Digital Cinema THEATRE COMPANY WEB S.No. THEATRE_NAME ADDRESS CITY ACTIVE DISTRICT STATE SEATING CODE NAME CODE 1 TH1011 Maheshwari 70Mm Cinema Road,4-2-198/2/3, Adilabad 500401 Adilabad Y Adilabad ANDHRA PRADESH UFO 698 2649 2 TH1012 Sri Venkataramana 70Mm Sirpur Kagzahnagar, Adilabad - 504296 Kagaznagar Y Adilabad ANDHRA PRADESH UFO 878 514 3 TH1013 Mayuri Theatre Mancherial, Adilabad, Mancherial - 504209, AP Mancherial Y Adilabad ANDHRA PRADESH UFO 354 1350 4 TH1014 Noor Jahan Picture Palace (Vempalli) Main Road, Vempalli, Pin- 516329, Andhar Pradesh Vempalli Y Adilabad ANDHRA PRADESH UFO 635 4055 5 TH1015 Krishna Theatre (Kadiri) Dist. - Ananthapur, Kadiri - 515591 AP Anantapur Y Anantapur ANDHRA PRADESH UFO 371 3834 Main Road, Gorantla, Dist. - Anantapur, Pin Code - 6 TH1016 Ramakrishna Theatre (Gorantla) Anantapur Y Anantapur ANDHRA PRADESH UFO 408 3636 515231 A.P 7 TH1017 Sri Varalakshmi Picture Palace Dharmavaram-515671 Ananthapur Distict Dharmavaram Y Anantapur ANDHRA PRADESH UFO 682 2725 8 TH1018 Padmasree Theatre (Palmaner) M.B.T Road, Palmaner, Chittor. Pin-517408 Chittoor Y Chittoor ANDHRA PRADESH UFO 587 3486 9 TH1021 Sri Venkateswara Theatre Chitoor Vellore Road, Chitoor, Dist Chitoor, AP Chittoor Y Chittoor ANDHRA PRADESH UFO 584 2451 10 TH1022 Murugan Talkies Kuppam, Dist. - Chittoor, AP Kuppam Y Chittoor ANDHRA PRADESH UFO 316 3696 Nagari, Venkateshmudaliyar St., Chittoor, Pin 11 TH1023 Rajeswari Theatre Nagari Y Chittoor ANDHRA PRADESH UFO 600 1993 517590 12 TH1024 Sreenivasa Theatre Nagari, Prakasam Road, Chithoor, -

E-Auction # 28

e-Auction # 28 Ancient India Hindu Medieval India Sultanates of India Mughal Empire Independent Kingdom Indian Princely States European Colonies of India Presidencies of India British Indian World Wide Medals SESSION I SESSION II Saturday, 24th Oct. 2015 Sunday, 25th Oct. 2015 Error-Coins Lot No. 1 to 500 Lot No. 501 to 1018 Arts & Artefects IMAGES SHOWN IN THIS CATALOGUE ARE NOT OF ACTUAL SIZE. IT IS ONLY FOR REFERENCE PURPOSE. HAMMER COMMISSION IS 14.5% Inclusive of Service Tax + Vat extra (1% on Gold/Silver, 5% on other metals & No Vat on Paper Money) Send your Bids via Email at [email protected] Send your bids via SMS or WhatsApp at 92431 45999 / 90084 90014 Next Floor Auction 26th, 27th & 28th February 2016. 10.01 am onwards 10.01 am onwards Saturday, 24th October 2015 Sunday, 25th October 2015 Lot No 1 to 500 Lot No 501 to 1018 SESSION - I (LOT 1 TO 500) 24th OCT. 2015, SATURDAY 10.01am ONWARDS ORDER OF SALE Closes on 24th October 2015 Sl.No. CATEGORY CLOSING TIME LOT NO. 1. Ancient India Coins 10:00.a.m to 11:46.a.m. 1 to 106 2. Hindu Medieval Coins 11:47.a.m to 12:42.p.m. 107 to 162 3. Sultanate Coins 12:43.p.m to 02:51.p.m. 163 to 291 4. Mughal India Coins 02:52.p.m to 06:20.p.m. 292 to 500 Marudhar Arts India’s Leading Numismatic Auction House. COINS OF ANCIENT INDIA Punch-Mark 1. Avanti Janapada (500-400 BC), Silver 1/4 Karshapana, Obv: standing human 1 2 figure, circular symbol around, Rev: uniface, 1.37g,9.94 X 9.39mm, about very fine. -

List of Cooperative Societies / Banks Registered Under MSCS Act W.E.F. 1986 Onwards Principal Date of Registration No

List of Cooperative Societies / Banks registered under MSCS Act w.e.f. 1986 onwards Principal Date of Registration No. S No Name of the Cooperative and its address Area of operation Type Remarks place Registration and file No. 1 All India Scheduled Castes Development Coop. Society All India Delhi 5.9.1986 MSCS Act/CR-1/86 Welfare Ltd.11, Race Course Road, New Delhi 110003 L.11015/3/86-L&M 2 Tribal Cooperative Marketing Development federation All India Delhi 6.8.1987 MSCS Act/CR-2/87 Marketing of India(TRIFED), Savitri Sadan, 15, Preet Vihar L.11015/10/87-L&M Community Center, Delhi 110092 3 All India Cooperative Cotton Federation Ltd., C/o All India Delhi 3.3.1988 MSCS Act/CR-3/88 Federation National Agricultural Cooperative Marketing L11015/11/84-L&M Federation of India Ltd. Sapna Building, 54, East of Kailash, New Delhi 110065 4 The British Council Division Calcutta L/E Staff Co- West Bengal, Tamil Kolkata 11.4.1988 MSCS Act/CR-4/88 Credit Converted into operative Credit Society Ltd , 5, Shakespeare Sarani, Nadu, Maharashtra & L.11016/8/88-L&M MSCS Kolkata, West Bengal 700017 Delhi 5 National Tree Growers Cooperative Federation Ltd., A.P., Gujarat, Odisha, Gujarat 13.5.1988 MSCS Act/CR-5/88 Credit C/o N.D.D.B, Anand-388001, District Kheda, Gujarat. Rajasthan & Karnataka L 11015/7/87-L&M 6 New Name : Ideal Commercial Credit Multistate Co- Maharashtra, Gujarat, Pune 22.6.1988 MSCS Act/CR-6/88 Amendment on Operative Society Ltd Karnataka, Goa, Tamil L 11016/49/87-L&M 23-02-2008 New Address: 1143, Khodayar Society, Model Nadu, Seemandhra, & 18-11-2014, Colony, Near Shivaji Nagar Police ground, Shivaji Telangana and New Amend on Nagar, Pune, 411016, Maharashtra 12-01-2017 Delhi. -

Madhya Pradesh 2011 the LAND of DIAMONDS

NOVEMBER Madhya Pradesh 2011 THE LAND OF DIAMONDS For updated information, please visit www.ibef.org 1 NOVEMBER Madhya Pradesh 2011 THE LAND OF DIAMONDS Contents Madhya Pradesh – An Introduction Infrastructure Status Business Opportunities Doing Business in Madhya Pradesh State Acts & Policies For updated information, please visit www.ibef.org 2 NOVEMBER Madhya Pradesh 2011 THE LAND OF DIAMONDS Madhya Pradesh Factfile → Indore, Gwalior, Jabalpur and Ujjain are some of the key cities of the state. → There are 11 agro-climatic conditions and a variety of soils available in the state to support cultivation of a wide range of crops. Madhya Parameters Pradesh Capital Bhopal Geographical area (sq km) 308,000 Administrative districts (No) 50 Population density (persons per sq km)* 236 Source: Maps of India Total population (million)* 72.5 → Madhya Pradesh is located in Central India. The state Male population (million)* 37.6 is bound in the North by Uttar Pradesh, the East by Chhattisgarh, the South by Maharashtra and the West Female population (million)* 34.9 by Gujarat and Rajasthan. Sex ratio (females per 1,000 males)* 930 Literacy rate (%)* 70.6 → The most commonly spoken language of the state is Hindi. English and Marathi are the other languages Sources: Government of Madhya Pradesh Website, www.mp.gov.in, used. *Provisional Data – Census 2011 For updated information, please visit www.ibef.org MADHYA PRADESH – AN INTRODUCTION 3 NOVEMBER Madhya Pradesh 2011 THE LAND OF DIAMONDS Madhya Pradesh in Figures … (1/2) Madhya Parameter All-States -

Faculty Handbook

2021 Indian Institute of Technology Indore Faculty Handbook Disclaimer The book may be used only as a handbook to appraise you with the rules and regulations followed at the Institute. The information in this handbook represents guidelines only. The rules, regulations and amount specified in this book are liable to change and it is not mandatory to carry out any amendment to this book every time any changes occur. At no point, the content of this book can be quoted as the rule and absolve the responsibility of the readers to be abreast with latest rule in force. Director’s Message I congratulate you for joining one of the best Institutes of the globe. You are welcome with an open heart to the IIT Indore community. The Institute campus is spread over 501 acres of land of which 200 acres is forest land. The entire campus is rich in flora and fauna. Different buildings and infrastructures have been architected and developed to ensure that the natural beauty remains intact. It creates a conducive environment enabling an individual to excel in academic, research, services, extra-curricular, co-curricular activities and hobbies. With the world class teaching, research and outreach facilities, I am sure that your appointment at IIT Indore will help in your overall development. The faculty members at IIT Indore are selected through rigorous stages of selection process and the chosen ones are one of the best in their field. We have experienced and well- trained staff to assist the Institute in the administrative and other support works. With continuously improving international and national ranking, IIT Indore is the preferred destination for most of the higher rank holders in the qualifying exams such as JEE(Advanced), GATE, JAM. -

Dr. Kailas Nath Katju

Dr. Kailas Nath Katju By MR. JUSTICE P. N. SAPRU Ex-Judge, High Court, Allahabad, and ex-M.P. (Rajya Sabha) Dr. Kailas Nath Katju belonged to a generation of lawyers and statesmen who helped to build up public life in this country and dedicated their lives to the cause of achieving freedom for this ancient land. He was born at Jaora on June 17, 1887. He came from a family of Kashmiri Brahmins settled in Jaora State, which is now a part of Madhya Pradesh, of which he became, before his retirement from active public life, the Chief Minister. He had his earlier education in Lahore. In 1905, he came over to Allahabad for legal studies and after topping the list of successful candidates in the Vakilship examination started practice under Pandit Prithinath Chak. He started practice in 1908 at Kanpur, where Pandit Prithinath Chak was the acknowledged leader of the Bar. For Pandit Prithinath he had the highest reverence. He looked upto him as a 'Guru', and many were the stories that he used to tell about Pandit Prithinath. Before his enrolment as a Vakil, Dr. Katju had a good University career. He was a Master of Arts of the Allahabad University in History, and to historical studies he remained devoted all his life. Endowed with a powerful mind his remarkable quality of thought, expression and understanding of human nature enabled him in no time to build up a solid legal practice at the Kanpur Bar. From Kanpur he shifted to Allahabad in 1914 and joined the Chambers of Sir Tej Bahadur Sapru.