Analysis of Impediments to Fair Housing Choice (AI)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Table of Contents

City of Santa Clarita Transit Development Plan Report Appendix Table of Contents Appendix A: Survey Instruments ................................................. A - 1 COMMUNITY SURVEY INSTRUMENT ............................................................................. A-1 ONBOARD SURVEY INSTRUMENT ................................................................................. A-2 COMMUTER SURVEY INSTRUMENT............................................................................... A-3 DIAL-A-RIDE SURVEYINSTRUMENT ................................................................................ A-4 SUPPLEMENTAL SCHOOL DAY SURVEY INSTRUMENT .................................................... A-6 Appendix B: Survey Frequencies .................................................. B - 1 COMMUNITY SURVEY FREQUENCIES ............................................................................. B-1 ONBOARD SURVEY FREQUENCIES ................................................................................. B-35 COMMUTER SURVEY FREQUENCIES .............................................................................. B-69 DIAL-A-RIDE SURVEY FREQUENCIES .............................................................................. B-88 SUPPLEMENTAL SCHOOL DAY SURVEY FREQUENCIES .................................................... B-102 Moore & Associates, Inc. | 2019 City of Santa Clarita Transit Development Plan Report Appendix A. Survey Instruments Exhibit A.1 Community Survey Instrument A - 1 Moore & Associates, Inc. | 2019 City of Santa -

Federal Register/Vol. 68, No. 181/Thursday, September 18, 2003

54728 Federal Register / Vol. 68, No. 181 / Thursday, September 18, 2003 / Notices DEPARTMENT OF ENERGY other interested parties to exchange information is necessary for the proper information and views on promoting performance of the functions of the Federal Energy Regulatory water-efficient products in the Commission, including whether the Commission marketplace. information shall have practical utility; [Docket Nos. RP00–336–014] The meeting will consist of several (b) the accuracy of the Commission’s panel discussions, and is open to the burden estimate; (c) ways to enhance El Paso Natural Gas Company; Notice public. The audience will have an the quality, utility, and clarity of the of Technical Conference opportunity to ask questions and information collected; and (d) ways to provide comments at the conclusion of minimize the burden of the collection of September 12, 2003. the meeting. information on the respondents, The Commission, in its order of DATES: The meeting will begin at 9 a.m. including the use of automated August 29, 2003 in this proceeding,1 on October 9, 2003. collection techniques or other forms of directed that a technical conference be ADDRESSES: The meeting will be held at information technology. held to address the issues raised by El the Hotel Washington, 15th and DATES: Written Paperwork Reduction Paso Natural Gas Company’s (El Paso) Pennsylvania Avenue, NW, Washington, Act (PRA) comments should be tariff compliance filing of August 1, DC 20004. submitted on or before November 17, 2003. FOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT: For 2003. If you anticipate that you will be Take notice that a technical more information on this meeting, submitting comments, but find it conference will be held on Wednesday, please see EPA’s Water Efficiency Web difficult to do so within the period of September 24, 2003, at 9 am, in a room page at www.epa.gov/owm/water- time allowed by this notice, you should to be designated at the Federal Energy efficiency/index.htm. -

The Cruise Passengers' Rights & Remedies 2016

PANEL SIX ADMIRALTY LAW: THE CRUISE PASSENGERS’ RIGHTS & REMEDIES 2016 245 246 ADMIRALTY LAW THE CRUISE PASSENGERS’ RIGHTS & REMEDIES 2016 Submitted By: HON. THOMAS A. DICKERSON Appellate Division, Second Department Brooklyn, NY 247 248 ADMIRALTY LAW THE CRUISE PASSENGERS’ RIGHTS & REMEDIES 2016 By Thomas A. Dickerson1 Introduction Thank you for inviting me to present on the Cruise Passengers’ Rights And Remedies 2016. For the last 40 years I have been writing about the travel consumer’s rights and remedies against airlines, cruise lines, rental car companies, taxis and ride sharing companies, hotels and resorts, tour operators, travel agents, informal travel promoters, and destination ground operators providing tours and excursions. My treatise, Travel Law, now 2,000 pages and first published in 1981, has been revised and updated 65 times, now at the rate of every 6 months. I have written over 400 legal articles and my weekly article on Travel Law is available worldwide on www.eturbonews.com Litigator During this 40 years, I spent 18 years as a consumer advocate specializing in prosecuting individual and class action cases on behalf of injured and victimized 1 Thomas A. Dickerson is an Associate Justice of the Appellate Division, Second Department of the New York State Supreme Court. Justice Dickerson is the author of Travel Law, Law Journal Press, 2016; Class Actions: The Law of 50 States, Law Journal Press, 2016; Article 9 [New York State Class Actions] of Weinstein, Korn & Miller, New York Civil Practice CPLR, Lexis-Nexis (MB), 2016; Consumer Protection Chapter 111 in Commercial Litigation In New York State Courts: Fourth Edition (Robert L. -

The 2021 Santa Clarita Valley Economic Outlook Volume 21 • Number 1 March 2021

SANTA CLARITA VALLEY 2021 ECONOMIC OUTLOOK The 2021 Santa Clarita Valley Economic Outlook Volume 21 • Number 1 March 2021 This publication was prepared by: The California Economic Forecast Mark Schniepp, Director 5385 Hollister Avenue, Box 207 Santa Barbara, California 93111 (805) 692-2498 [email protected] Visit our website at: www.californiaforecast.com Copyright 2021 by the California Economic Forecast Reproduction of this document or any portion therein is prohibited without the expressed written permission of the California Economic Forecast. All queries regarding this publication should be directed to the California Economic Forecast. 2021 ECONOMIC OUTLOOK 1 SANTA CLARITA VALLEY 2021 ECONOMIC OUTLOOK Table of Contents Executive Summary 3 Employment and Workforce 17 Residential Real Estate 29 Commercial Real Estate 35 New Development 41 Acknowledgements 53 2021 ECONOMIC OUTLOOK 2 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY General U.S. Economy California The Santa Clarita Valley The Outlook 3 CALIFORNIA ECONOMIC FORECAST EXECUTIVE SUMMARY / SANTA CLARITA VALLEY 2021 ECONOMIC OUTLOOK Executive Summary by Mark Schniepp March 23, 2021 index Consumer Sentiment / University of Michigan Survey General U.S. Economy 1985=100 September 2017 -- March 2021 100 After the first 90 days of 2021, the evidence 95 on the U.S. economy remains mixed. Through 90 December, the economy was losing momentum 85 as new restrictions on businesses were 80 mandated during the winter surge in COVID-19 cases. 75 70 The surge has clearly abated and despite new 65 Sep-17 Mar-18 Sep-18 Mar-19 Sep-19 Mar-20 Sep-20 Mar-21 predictions of another surge by infectious health professionals, we believe the pandemic is now fading away. -

Port-Of-Call Options

A SYSTEMATIC APPROACH PORT-OF-CALL OPTIONS V7.10.12.02.20 HOW IS THE INDUSTRY COMING BACK? © Bermello, Ajamil & Partners, Inc. STATUS OF REGULATORY APPROVALS TO SAIL SOURCE: B&A CRUISE DASHBOARD As of 12.02.20, © Bermello, Ajamil & Partners, Inc. SOURCE: B&A CRUISE DASHBOARD CRUISE INDUSTRY RETURN TO SERVICE ANNOUNCEMENTS ) As of 12.02.20 12.02.20 10.01.20 SHIPS SAILING © Bermello, Ajamil & Partners, Inc. CRUISE RESTART ANNOUNCEMENTS ) JUN JUL AUG SEP OCT NOV DEC • HURTIGRUTEN • TUI • MSC • COSTA • AIDA • HERITAGE EXPED • RCI (SINGAPORE) • SEADREAM • HAPAG-LLOYD • SILVERSEA (CHARTER) • NICKO CRUISES • CORAL EXPEDITIONS • MITSUI OSK • FRED. OLSEN • PAUL GAUGUIN • BLACK SEA CRUISES • NYK CRUISES • ASTRO OCEAN • DREAM CRUISES • ARANUI CRUISES • VENUS CRUISE LINE 2020 • PONANT • VARIETY VOYAGES • CROISIEUROPE JAN FEB MAR APR MAY JUN JUL • SEABOURN • CARNIVAL • NORWEGIAN • PRINCESS • CELEBRITY • DISNEY • CUNARD • P&O • VIRGIN • P&O AUSTRALIA • CRYSTAL • HOLLAND AMERICA • MARELLA • FRED OLSEN • AZAMARA • OCEANIA • SCENIC • CELESTYAL 10.01.20 • REGENT • VIKING SHIPS• WINDSTARSAILING • SAGA • SEACLOUD • RITZ • SILVERSEA 2021 THERE WILL BE MOVEMENT As of 11.30.20, SOURCE: B&A CRUISE DASHBOARD © Bermello, Ajamil & Partners, Inc. GLOBAL FLEET ANNUAL WITHDRAWALS (2020 ANNOUNCED TO DATE, 2021+ ANTICIPATED) As of 11.10.20, B&A 40,000 30 35,000 25 30,000 20 25,000 20,000 15 Ships Lower Berths Lower 15,000 10 10,000 5 5,000 0 0 Lower Berths Ships © Bermello, Ajamil & Partners, Inc. GLOBAL FLEET WITHDRAWALS (2020 ANNOUNCED TO DATE, 2021+ ANTICIPATED) As -

Helping Families Thrive. Center & Foundation Boards

A NNU A L R EPO R T 2 0 1 6 / 2 0 1 7 Helping families thrive. Center & Foundation Boards Center Board Officers (July - December 2016) William Cooper - Chair Mission Michael Berger - Vice Chair Dr. David Wong –Treasurer The Child & Family Center helps build a healthy Gloria Mercado Fortine –Secretary Steve Zimmer - Immed. Past Chair Santa Clarita Valley by providing mental health, (January - June 2017) Michael Berger - Chair behavioral and education services to children, Cheri Fleming –Vice Chair Michael Lebecki - Vice Chair adults and families. Dr. Marc Winger –Treasurer Ginger LeVang –Secretary William Cooper - Immed. Past Chair Foundation Board Officers (July - December 2016) Vision Nick Lentini - Chair Michael Lebecki – Vice Chair At the Child & Family Center, children, adults, and Chris Blazey – Treasurer Jane Bettencourt-Soto - Secretary families can easily access the help they need in a Members safe and nurturing environment. Responding to the Fred Arnold Lois Bauccio community’s need for services, the Child & Family Amanda Benson Joyce Carson Center continues to grow and expand. Reaching out Barbara Cochran Diana Cusumano to new areas of need, the Center provides children Michael DeLorenzo Neil Fitzgerald and adults the opportunity to live in healthy, Cheri Fleming John Geraci supportive relationships that encourage them to Stephanie Graziano Dan Gunning become responsible, caring citizens. Kiki Hacker Linda Hafizi G. Marshall Hann Alicia Humphries Darren Hernandez Debbie Holbrook Don Hubbard Jenny Ketchepaw Charlotte Kleeman Ken Kreyenhagen Terry Martin Laina McFerren John Musella Linda Pedersen Doreen Chastain-Shine Diane Stewart Steve Sturgeon Irene Thomas-Johnson Silvia Weeks Vanessa Wilk Michelle Witkin, PhD Apo Yessayan 2016/17 ANNUAL REPORT | 3 Message from our President/CEO and Board Chair The Child & Family Center, just like any other vibrant and evolving organization, continues to change over time to meet the needs of our clients and communities. -

Princess Cruises and Fincantieri Sign Contracts for Two Next-Generation Cruise Ships Santa Clarita, California, Usa / Trieste

PRINCESS CRUISES AND FINCANTIERI SIGN CONTRACTS FOR TWO NEXT-GENERATION CRUISE SHIPS SANTA CLARITA, CALIFORNIA, USA / TRIESTE, ITALY (March 27, 2019) – Princess Cruises and Fincantieri announced today the signing of the final contracts for the construction of two next-generation 175,000-ton cruise ships, which will be the largest ships built so far in Italy with deliveries scheduled in Monfalcone in late 2023 and in spring 2025. This announcement follows the initial signing of a memorandum of agreement between the two parties in July 2018. The vessels will each accommodate approximately 4,300 guests and will be based on a next- generation platform design, being the first Princess Cruises ships to be dual-fuel powered primarily by Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG). LNG is the marine industry’s most environmentally friendly advanced fuel technology and the world’s cleanest fossil fuel, which will significantly reduce air emissions and marine gasoil usage. “Princess Cruises continues to grow globally -- adding new ships to our fleet built by our long- time trusted ship building partner, Fincantieri, who brings decades of expertise to these next- generation cruise ships” said Jan Swartz, Princess Cruises President. “Even more exciting is that these two ships are being designed to include our MedallionClass platform, powered by OceanMedallion, the most advanced wearable device available within the global hospitality industry”. Giuseppe Bono, CEO of Fincantieri, commented on the announcement: “This result proves, once again, the trust we receive from the market, which allows us to look to the future with ambition. It honors our great work focused on innovation thanks to which we have been able to offer to the client a record-breaking proposal not only in terms of size. -

Valencia Town Center 24300-24305 TOWN CENTER DRIVE, VALENCIA, CALIFORNIA 91355

FOR LEASE Valencia Town Center 24300-24305 TOWN CENTER DRIVE, VALENCIA, CALIFORNIA 91355 11TH LARGEST RETAIL CENTER IN LA COUNTY, RANKED BY GROSS LEASABLE AREA Valencia Town Center Drive (“VTC”) is one of the most successful mixed-use projects in the nation. The VTC project consists 395,037 of square feet of office and retail space. There are four class “A” office buildings (“VTC I – IV”) anchored by Princess Cruises worldwide headquarters (Carnival Corporation, S&P: A-) and two parking structures with plenty of parking. The project is inline of the Westfield Valencia Town Center regional mall (“Westfield VTC”), the 244-room Hyatt Valencia & Santa Clarita Conference Center (“Hyatt Valencia”), a 12-screen Edwards’s multiplex IMAX theater, 551 luxury apartment units, and a 57,000 square foot Medical facility. The available space for lease is on the ground floors of the two office buildings which serve as VTC’s “main street” connecting the area’s major expressway (McBean Parkway) with the “Westfield VTC” enclosed mall. This main street is distinguished by its Entertainment Plaza, anchored by Gold’s Gym and Edwards Grand Palace Theaters. VALENCIA TOWN CENTER’S NEWEST RESTAURANTS: CONTACT INFORMATION Retail Leasing Cody Chiarella First Vice President +1 818 502 6730 [email protected] www.cbre.com/lanorth Lic. 01754878 FOR LEASE Valencia Town Center 24300-24305 TOWN CENTER DRIVE, VALENCIA, CALIFORNIA 91355 LOCATION INFORMATION Retail Availabilities Valencia is one of America’s most respected master-planned communities. Valencia’s residents can live, work, shop, play and thrive at The Valencia Suite Rental Rate Space Available Availability Town Center. -

Princess Cruises Pause Extension Through May 14, 2021

Princess Cruises Pause Extension through May 14, 2021 As Princess Cruises continues to prepare and develop its plans to meet the “Framework for Conditional Sailing Order” issued by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), in addition to the uncertainty around travel restrictions, the company is extending its pause of guest cruise vacations on ships sailing through May 14, 2021. This includes sailings in the Caribbean, the California Coast, along with early season Alaska and Europe cruises and select other voyages for deployment purposes. Guests have the option to stick with us by accepting this special higher value Future Cruise Credit (FCC) offer: • 100% value of cruise fare paid as a refundable FCC • Bonus non-refundable FCC equal to 25% of the cruise fare paid* *Bonus FCC minimum of $50 per person (minimum varies by FCC currency: $50USD, $50CAD, $50AUD, £50GBP, €50EUR, ¥5,000) This requires no action from the guest and gives our team a chance to shine at a later date by using the above Future Cruise Credits on any voyage booked by May 1, 2022 and sailing by December 31, 2022. Princess will protect travel advisor commission on bookings for cancelled cruises that were paid in full in recognition of the critical role they play in the cruise line’s business and success. Alternatively, guests can forfeit the higher value FCC offer and request a refund for all money paid on their booking by using this online form. Guests have until February 15, 2021 to decide, or they will automatically receive the default offer listed above. -

Summer 2019 the Millergram Is Designed and Formatted by Tim Noble, Our Good Friend from Melbourne, Australia and a Former Navigating Officer with the Blue Star Line

The & MILLERGRAM by Bill Miller billmilleratsea.com Summer 2019 The Millergram is designed and formatted by Tim Noble, our good friend from Melbourne, Australia and a former navigating officer with the Blue Star Line. AIDA CRUISES: Just in case you had to know, Aida has beat Branson’s Virgin Cruises by offering the very first tattoo parlor to hit the high seas. It is aboard the Mein Schiff 2 and already popular with mostly younger German cruisers. Virgin will go a step further – they’ll also offer a piercing salon on its new cruise liners. Page 1 ALONG THE PROMENADE: Celebrities – royalty, politicians, but especially Hollywood stars – added to the glamour, even the sheer fascination of the old liners. They were all but regulars on the liners. But photos of them are rare. Some were destroyed, others simply discarded. But here’s Rita Hayworth, arriving at Pier 86 aboard the United States. The date is 1955. Page 2 BOOKS: Happily & generously, Capt Aseem Hashmi – master of the Queen Mary 2 – has contributed a fine foreword to our new book celebrating 50 years of the QE2. The Captain is seen below, just last winter, before the re-opened QE2 out in Dubai. We had a thorough read of Union-Castle Line: The Post-War Liners, published by Ships Illustrated and written by the late Peter Newall. Wonderful photos & fine text of such great liners on the UK-Africa run such as the Edinburgh Castle, Braemar Castle, Pendennis Castle, Windsor Castle (seen below) and then the last of them (1961), the Transvaal Castle. -

Printmgr File

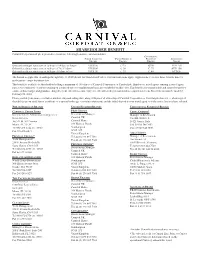

SHAREHOLDER BENEFIT Carnival Corporation & plc is pleased to extend the following benefit to our shareholders: CONTINENTAL NORTH AMERICAN UNITED KINGDOM EUROPEAN AUSTRALIAN BRANDS BRANDS BRANDS BRAND Onboard credit per stateroom on sailings of 14 days or longer US $250 £125 €200 AUD 250 Onboard credit per stateroom on sailings of 7 to 13 days+ US $100 £ 50 € 75 AUD 100 Onboard credit per stateroom on sailings of 6 days or less US $ 50 £ 25 € 40 AUD 50 The benefit is applicable on sailings through July 31, 2010 aboard the brands listed below. Certain restrictions apply. Applications to receive these benefits must be made prior to cruise departure date. This benefit is available to shareholders holding a minimum of 100 shares of Carnival Corporation or Carnival plc. Employees, travel agents cruising at travel agent rates, tour conductors or anyone cruising on a reduced-rate or complimentary basis are excluded from this offer. This benefit is not transferable and cannot be used for casino credits/charges and gratuities charged to your onboard account. Only one onboard credit per shareholder-occupied stateroom. Reservations must be made by February 28, 2010. Please provide your name, reservation number, ship and sailing date, along with proof of ownership of Carnival Corporation or Carnival plc shares (i.e., photocopy of shareholder proxy card, shares certificate or a current brokerage or nominee statement) and the initial deposit to your travel agent or to the cruise line you have selected. NORTH AMERICAN BRANDS UNITED KINGDOM BRANDS CONTINENTAL EUROPEAN BRANDS CARNIVAL CRUISE LINES P&O CRUISES COSTA CRUISES* Guest Solutions Administration Supervisor Reservations Manager Manager of Reservation Guest Services Carnival UK Via XII Ottobre, 2 3655 N.W. -

79667 FCCA Profiles

TableTable ofofContentsContents CARNIVAL CORPORATION Mark M. Kammerer, V.P., Worldwide Cruise Marketing . .43 Micky Arison, Chairman & CEO (FCCA Chairman) . .14 Stein Kruse, Senior V.P., Fleet Operations . .43 Giora Israel, V.P., Strategic Planning . .14 A. Kirk Lanterman, Chairman & CEO . .43 Francisco Nolla, V.P., Port Development . .15 Gregory J. MacGarva, Director, Procurement . .44 Matthew T. Sams, V.P., Caribbean Relations . .44 CARNIVAL CRUISE LINES Roger Blum, V.P., Cruise Programming . .15 NORWEGIAN CRUISE LINE Gordon Buck, Director, Port Operations. .16 Capt. Kaare Bakke, V.P. of Port Operations . .48 Amilicar “Mico” Cascais, Director, Tour Operations . .16 Sharon Dammar, Purchasing Manager, Food & Beverages . .48 Brendan Corrigan, Senior V.P., Cruise Operations . .16 Alvin Dennis, V.P., Purchasing & Logistics Bob Dickinson, President . .16 (FCCA Purchasing Committee Chairman) . .48 Vicki L. Freed, Senior V.P. of Sales & Marketing . .17 Colin Murphy, V.P, Land & Air Services . .48 Joe Lavi, Staff V.P. of Purchasing . .18 Joanne Salzedo, Manager, International Shore Programs . .49 David Mizer, V.P., Strategic Sourcing Global Source . .18 Andrew Stuart, Senior V.P., Marketing & Sales . .49 Francesco Morrello, Director, Port Development Group . .18 Colin Veitch, President & CEO . .49 Gardiner Nealon, Manager, Port Logistics . .19 Mary Sloan, Director, Risk Management . .19 PRINCESS CRUISES Terry L. Thornton, V.P., Marketing Planning Deanna Austin, V.P., Yield Management . .52 (FCCA Marketing Committee Chairman) . .19 Dean Brown, Executive V.P., Customer Service Capt. Domenico Tringale, V.P., Marine & Port Operations . .19 & Sales; Chairman & CEO of Princess Tours . .52 Jeffrey Danis, V.P., Global Purchasing & Logistics . .52 CELEBRITY CRUISES Graham Davis, Manager, Shore Operations, Caribbean and Atlantic .