Manuel, Alexander

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Recueil Des Actes Administratifs

RECUEIL DES ACTES ADMINISTRATIFS Numéro 33 1er juillet 2010 RECUEIL des ACTES ADMINISTRATIFS N° 33 du 1er juillet 2010 SOMMAIRE ARRÊTÉS DU PRÉFET DE DÉPARTEMENT BUREAU DU CABINET Objet : Liste des établissements recevant du public et immeuble de grande hauteur implantés dans la Somme au 31 décembre 2009 et soumis aux dispositions du règlement de sécurité contre les risques d'incendie et de panique-----1 Objet : Médaille d’honneur agricole-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------1 Objet : Médaille d’honneur régionale, départementale et communale--------------------------------------------------------6 Objet : délégation de signature : cabinet-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------27 Objet : délégation de signature : permanences des sous-préfets et du secrétaire général pour les affaires régionales 28 DIRECTION DES AFFAIRES JURIDIQUES ET DE L'ADMINISTRATION LOCALE Objet : CNAC du 8 avril 2010 – création d'un ensemble commercial à VILLERS-BRETONNEUX------------------29 DIRECTION DÉPARTEMENTALE DES TERRITOIRES ET DE LA MER DE LA SOMME Objet : Règlement intérieur de la Commission locale d’amélioration de l’habitat du département de la Somme-----30 Objet : Arrêté portant sur la régulation des blaireaux--------------------------------------------------------------------------31 Objet : Arrêté fixant la liste des animaux classés nuisibles et fixant les modalités de destruction à tir pour la période du 1er juillet 2010 au 30 juin 2011 pour le -

ANNEXE 1 DÉCOUPAGE DES SECTEURS AVEC RÉPARTITION DES COMMUNES PAR SECTEUR Secteur 1 : AUTHIE (Bassin-Versant De L’Authie Dans Le Département De La Somme)

ANNEXE 1 DÉCOUPAGE DES SECTEURS AVEC RÉPARTITION DES COMMUNES PAR SECTEUR Secteur 1 : AUTHIE (bassin-versant de l’Authie dans le département de la Somme) ACHEUX-EN-AMIENOIS 80003 LOUVENCOURT 80493 AGENVILLE 80005 LUCHEUX 80495 ARGOULES 80025 MAISON-PONTHIEU 80501 ARQUEVES 80028 MAIZICOURT 80503 AUTHEUX 80042 MARIEUX 80514 AUTHIE 80043 MEZEROLLES 80544 AUTHIEULE 80044 MONTIGNY-LES-JONGLEURS 80563 BARLY 80055 NAMPONT-SAINT-MARTIN 80580 BAYENCOURT 80057 NEUILLY-LE-DIEN 80589 BEALCOURT 80060 NEUVILLETTE 80596 BEAUQUESNE 80070 OCCOCHES 80602 BEAUVAL 80071 OUTREBOIS 80614 BERNATRE 80085 PONCHES-ESTRUVAL 80631 BERNAVILLE 80086 PROUVILLE 80642 BERTRANCOURT 80095 PUCHEVILLERS 80645 BOISBERGUES 80108 QUEND 80649 BOUFFLERS 80118 RAINCHEVAL 80659 BOUQUEMAISON 80122 REMAISNIL 80666 BREVILLERS 80140 SAINT-ACHEUL 80697 BUS-LES-ARTOIS 80153 SAINT-LEGER-LES-AUTHIE 80705 CANDAS 80168 TERRAMESNIL 80749 COIGNEUX 80201 THIEVRES 80756 COLINCAMPS 80203 VAUCHELLES-LES-AUTHIE 80777 CONTEVILLE 80208 VERCOURT 80787 COURCELLES-AU-BOIS 80217 VILLERS-SUR-AUTHIE 80806 DOMINOIS 80244 VIRONCHAUX 80808 DOMLEGER-LONGVILLERS 80245 VITZ-SUR-AUTHIE 80810 DOMPIERRE-SUR-AUTHIE 80248 VRON 80815 DOULLENS 80253 ESTREES-LES-CRECY 80290 FIENVILLERS 80310 FORT-MAHON-PLAGE 80333 FROHEN-SUR-AUTHIE 80369 GEZAINCOURT 80377 GROUCHES-LUCHUEL 80392 GUESCHART 80396 HEM-HARDINVAL 80427 HEUZECOURT 80439 HIERMONT 80440 HUMBERCOURT 80445 LE BOISLE 80109 LE MEILLARD 80526 LEALVILLERS 80470 LIGESCOURT 80477 LONGUEVILLETTE 80491 Secteur 2 : MAYE (bassin-versant de la Maye) ARRY 80030 BERNAY-EN-PONTHIEU -

D'assainissement Non Collectif (SPANC)

Acheux-en-Amiénois • Albert • Arquèves • Auchonvillers • Authie • Authuille ce que dit la loi protéger l’eau • Aveluy • Bayencourt • Bazentin • Beaucourt-sur-l’Ancre • Beaumont- Hamel • Bécordel-Bécourt • Bertrancourt • Bouzincourt • Bray-sur-Somme • Depuis la Loi du 3 janvier 1992, toute habitation doit être reliée à un réseau les bons conseils LEBuire-sur-l’Ancre SERVICE • Bus-lès-Artois • Cappy • Carnoy PUBLIC • Chuignolles • Coigneux d’assainissement collectif ou être dotée d’un système d’assainissement non • Colincamps • Contalmaison • Courcelette • Courcelles-au-Bois • Curlu • collectif. Dernancourt • Eclusier-Vaux • Englebelmer • Etinehem • Forceville • Fricourt • L’assainissement fait appel à la participation de chacun et certains réflexes d’AssainissementFrise • Grandcourt • Harponville • Hédauville • Hérissart • Irles • La Neuville- sont à prendre au quotidien pour en assurer la bonne efficacité. lès-Bray • Laviéville • Léalvillers • Louvencourt • Mailly-Maillet • Mametz • À ce titre, la Communauté de Communes du Pays du Coquelicot a procédé aux Maricourt • Marieux • Méaulte • Méricourt-sur-Somme • Mesnil-Martinsart études du schéma directeur d’assainissement des communes de son territoire Non• Millencourt •Collectif Miraumont • Montauban-de-Picardie (SPANC) • Morlancourt • Ovillers- et a élaboré les plans de zonage qui ont permis de définir les zones où sera Les eaux pluviales doivent être collectées et traitées séparément par des la-Boisselle • Pozières • Puchevillers • Pys • Raincheval • Saint-Léger-lès-Authie mis en place l’assainissement non collectif, conformément aux décisions des ouvrages indépendants de la filière de traitement des eaux usées. • Senlis-le-Sec • Suzanne • Thiepval • Thièvres • Toutencourt • Varennes • communes. Vauchelles-lès-Authie • Ville-sur-Ancre La Loi sur l’Eau et les Milieux Aquatiques du 30 décembre 2006 précise évitez la mousse l’ensemble des obligations qui nous incombent dans le domaine de l’eau. -

Avis D'enquete Publique

Communauté de communes du Pays du Coquelicot AVIS D’ENQUETE PUBLIQUE du 27 août 2018 au 27 septembre 2018 inclus. Concernant l’enquête publique sur le projet de Plan Local d’Urbanisme intercommunal (PLUi) valant Programme Local de l’Habitat (PLH) arrêté par le Conseil Communautaire et comprenant les communes suivantes : ACHEUX-EN-AMIENOIS, ALBERT, ARQUEVES, AUCHONVILLERS, AUTHIE, AUTHUILLE, AVELUY, BAYENCOURT, BAZENTIN, BEAUCOURT-SUR-L’ANCRE, BEAUMONT-HAMEL, BECORDEL-BECOURT, BERTRANCOURT, BOUZINCOURT, BRAY-SUR-SOMME, BUIRE-SUR-ANCRE, BUS-LES-ARTOIS, CAPPY, CARNOY, CHUIGNOLLES, COIGNEUX, COLINCAMPS, CONTALMAISON, COURCELETTE, COURCELLES-AU-BOIS, CURLU, DERNANCOURT, ECLUSIER-VAUX, ENGLEBELMER, ETINEHEM-MERICOURT, FORCEVILLE-EN-AMIENOIS, FRICOURT, FRISE, GRANDCOURT, HARPONVILLE, HEDAUVILLE, HERISSART, IRLES, LA NEUVILLE-LES-BRAY, LAVIEVILLE, LEALVILLERS, LOUVENCOURT, MAILLY-MAILLET, MAMETZ, MARICOURT, MARIEUX, MEAULTE, MESNIL-MARTINSART, MILLENCOURT, MIRAUMONT, MONTAUBAN-DE-PICARDIE, MORLANCOURT, OVILLERS-LA-BOISELLE, POZIERES, PUCHEVILLERS, PYS, RAINCHEVAL, SAINT-LEGER-LES-AUTHIE, SENLIS-LE-SEC, SUZANNE, THIEVRES, THIEPVAL, TOUTENCOURT, VARENNE-EN-CROIX, VAUCHELLES-LES-AUTHIE, VILLE-SUR-ANCRE Par arrêté en date du 3 août 2018, le Président de la Communauté de Communes du Pays du Coquelicot a ordonné l’ouverture de l’enquête publique sur le projet de PLUi arrêté par le Conseil Communautaire et fixer l’ensemble des modalités de l’enquête publique. VU : - le Code de l’Environnement, - le Code de l’Urbanisme, - la délibération du Conseil Communautaire en date du 24 juin 2013 ayant prescrit l’élaboration du Plan Local d’Urbanisme intercommunal (PLUi), - la délibération du Conseil Communautaire en date du 19 février 2018 ayant arrêté le projet de PLUi, - la décision n° E18000103/80 en date du 19 juin 2018 de M. -

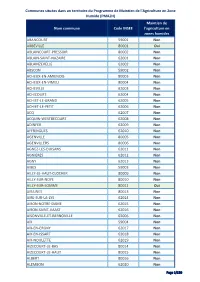

(PMAZH) Nom Commune Code INSEE

Communes situées dans un territoire du Programme de Maintien de l'Agriculture en Zone Humide (PMAZH) Maintien de Nom commune Code INSEE l'agriculture en zones humides ABANCOURT 59001 Non ABBEVILLE 80001 Oui ABLAINCOURT-PRESSOIR 80002 Non ABLAIN-SAINT-NAZAIRE 62001 Non ABLAINZEVELLE 62002 Non ABSCON 59002 Non ACHEUX-EN-AMIENOIS 80003 Non ACHEUX-EN-VIMEU 80004 Non ACHEVILLE 62003 Non ACHICOURT 62004 Non ACHIET-LE-GRAND 62005 Non ACHIET-LE-PETIT 62006 Non ACQ 62007 Non ACQUIN-WESTBECOURT 62008 Non ADINFER 62009 Non AFFRINGUES 62010 Non AGENVILLE 80005 Non AGENVILLERS 80006 Non AGNEZ-LES-DUISANS 62011 Non AGNIERES 62012 Non AGNY 62013 Non AIBES 59003 Non AILLY-LE-HAUT-CLOCHER 80009 Non AILLY-SUR-NOYE 80010 Non AILLY-SUR-SOMME 80011 Oui AIRAINES 80013 Non AIRE-SUR-LA-LYS 62014 Non AIRON-NOTRE-DAME 62015 Non AIRON-SAINT-VAAST 62016 Non AISONVILLE-ET-BERNOVILLE 02006 Non AIX 59004 Non AIX-EN-ERGNY 62017 Non AIX-EN-ISSART 62018 Non AIX-NOULETTE 62019 Non AIZECOURT-LE-BAS 80014 Non AIZECOURT-LE-HAUT 80015 Non ALBERT 80016 Non ALEMBON 62020 Non Page 1/130 Communes situées dans un territoire du Programme de Maintien de l'Agriculture en Zone Humide (PMAZH) Maintien de Nom commune Code INSEE l'agriculture en zones humides ALETTE 62021 Non ALINCTHUN 62022 Non ALLAINES 80017 Non ALLENAY 80018 Non ALLENNES-LES-MARAIS 59005 Non ALLERY 80019 Non ALLONVILLE 80020 Non ALLOUAGNE 62023 Non ALQUINES 62024 Non AMBLETEUSE 62025 Oui AMBRICOURT 62026 Non AMBRINES 62027 Non AMES 62028 Non AMETTES 62029 Non AMFROIPRET 59006 Non AMIENS 80021 Oui AMPLIER 62030 Non AMY -

Beaumont Hamel - SE01-2 Mémorial Du Commonwealth « 29 Th Division (Newfoundland) Memorial »

Association « Paysages et Sites de mémoire de la Grande Guerre » SECTEUR K - LA VALLÉE DE L’ANCRE SE01 SE02 SE03 SE04 Description générale du secteur mémoriel Le secteur mémorial de la « Vallée de l'Ancre » se situe sur le plateau de l’Amiénois, sur les rives est et ouest de la rivière Ancre – un affluent de la Somme. Son organisation spatiale d’openfield en fait un paysage agraire ouvert, ponctué de villages, hameaux et bois. Le « saillant de Leipzig », sur les hauteurs, culmine à plus de 140m à l’est et constitue une véritable forteresse naturelle, dominant la vallée de l’Ancre. Au plan géologique, la vallée présente un limon argilo-sableux, tandis que le sol du plateau est constitué tant d’argile que de limon. Ces caractéristiques géologiques ont été utilisées pendant le conflit et ont eu un impact sur l’offensive. Le secteur mémoriel « Vallée de l'Ancre » regroupe quatre éléments constitutifs. Son homogénéité, tant chronologique qu’environnementale, architecturale et spatiale, en fait un lieu mémoriel unique, doté d’un maillage très dense de mémoriaux, cimetières et paysages marqués par le conflit. Chacun se distingue par une identité individuelle forte et complémentaire. C’est un territoire rural totalement « sacralisé », pour lequel la dimension funéraire de la Première Guerre mondiale constitue la première caractéristique : outre les stèles des combattants inhumés dans les cimetières, c’est surtout le « missing » ou « disparu » en anglais qui se trouve au cœur du discours architectural. En parallèle, la proximité et le principe de co-visibilité entre chaque élément constitutif contribuent à définir l’identité symbolique, esthétique et mémorielle unique qui caractérise cet espace, né de la bataille de la Sommeen 1916 (1 er juillet-18 novembre). -

Surname Forenames Date Died Age Service Number Rank Battalion Regiment / Unit / Ship Where Buried / Remembered History

Surname Forenames Date Died Age Service Number Rank Battalion Regiment / Unit / Ship Where Buried / Remembered History Died of wounds. Enlisted August 1916 to Army Service Corps (serial number T4/21509). Only Brandhoek New Military Cemetery No 3 Abrey James 18/08/1917 37 Army 42772 Private 12th Royal Irish Rifles Royal Irish Rifles is recorded on Medal Card. Born Rochford. Married to Miriam of 4 Bournes Belgium Green Southchurch in 1903 Died of wounds received while serving as a stretcher bearer. Enlisted April 1916. Born Rayleigh son of Harry of Weir Cottages. Married to Lily, 8 Guildford Road Southend. Employed as a carman. A member of the Peculiar People religious group. Remembered on Rayleigh Memorial. Adey Fred William 22/10/1916 23 Army 40129 Private 2nd Essex Regiment Etaples Military Cemetery France His brother Harry enlisted 1/9/191 into Middlesex Regiment (service number 2897) and transferred to Machine Gun Corps (13419) being discharged 30/9/1916 through wounds. Inscription on his headstone "Free from a world of grief and sin with God eternally shut in" Died at Shamran Mamourie. Went overseas 5/12/1915. Born Tooting and lived in Rochford. Son Affleck William 05/09/1916 Army 8379 Sergeant 1st Oxfordshire & Buckingham Regiment Basra Memorial Iraq of William and Rebecca The Stores Ashingdon Rochford. Married to Mary in 1915. Killed in action. Born Plaistow. Son of Walter and Eliza of Mount Bovers Lane Hawkwell. Married Feuchy Chapel British Cemetery Wancourt Allen John Charles 10/05/1917 28 Army 33626 Private 2nd Suffolk Regiment (Alice / Sarah) with two children, occupation groom-gardener. -

World War 1 Casualities from Weardale Les Blackett.Xlsx

Les Blackett Database First World War Casualties from Weardale (1914-1918) Surname Forenames Database Address Village Parish Regiment Battalion Rank Date of Death Regimental Place of Next of Kin Burial Place War Mamorial Age at Place of Death Type of Casualty Notes War reference Number Enlistment Death Record Adamson Richard Bell 57High Rookhope Rookhope Durham Light 1st/6th Battalion Corporal 05/11/1915 1957 Son of Margaret THIEPVAL 26 No Redburn Infantry Adamson, of High MEMORIAL Red Burn, Rookhope, Eastgate, Co. Durham, and the late Ambrose Adamson Adamson Robert 58 Princess Rookhope Rookhope Durham Light 1st/6th Battalion Private 07/02/19161956 Rookhope Son of Pearson and PERTH CEMETERY 19 France and Killed in action No Hodgson Cottage Infantry Lucy Margaret (CHINA WALL) Flanders Adamson, of Princess Cottages, Rookhope, Co. Durham. Airey Edward 154East End Frosterley Frosterley York and 6th (Service) Private 10/05/1918 33562,12275 Bishop Son of Samuel and MONT HUON 19 France Died Occupation on Yes (20) Lancaster Battalion 6,42756 Auckland Mary Elizabeth Airey, MILITARY enlistment - Railway Regiment of Front St., CEMETERY, LE Porter - Born in Frosterley TREPORT Sunderland - 1911 Census, Living at White Kirkley, Frosterley Allison Joseph 70 Graham Stanhope Stanhope Durham Light 26th Battalion Private 30/09/1916 4375 Bishop Brother of Stanhope 35 Home Died Died of Pneumonia No William Street Infantry Auckland Christopher Allison Cemetary in the U.K. - Prior to of Graham Street, the War he is Stanhope described as being employed as a Plate Layer in the Quarries Anderson Alexander 75Market Wolsingham Wolsingham Durham Light 1st/8th Battalion Private 323016 5610 Bishop Son of the late Mrs LIDZBARK 31 Poland Died whilst a Born in Coldstream, Yes Place Infantry Auckland Katherine Anderson WARMINSKI WAR prisoner Berwickshire. -

Sectorisation Par Commune

Conseil départemental de la Somme / Direction des Collèges Périmètre de recrutement des collèges par commune octobre 2019 Code communes du secteur Libellé du secteur collège commune 80001 Abbeville voir sectorisation spécifique 80002 Ablaincourt-Pressoir CHAULNES 80003 Acheux-en-Amiénois ACHEUX EN AMIENOIS 80004 Acheux-en-Vimeu FEUQUIERES EN VIMEU 80005 Agenville BERNAVILLE 80006 Agenvillers NOUVION AGNIERES (ratt. à HESCAMPS) POIX 80008 Aigneville FEUQUIERES EN VIMEU 80009 Ailly-le-Haut-Clocher AILLY LE HAUT CLOCHER 80010 Ailly-sur-Noye AILLY SUR NOYE 80011 Ailly-sur-Somme AILLY SUR SOMME 80013 Airaines AIRAINES 80014 Aizecourt-le-Bas ROISEL 80015 Aizecourt-le-Haut PERONNE 80016 Albert voir sectorisation spécifique 80017 Allaines PERONNE 80018 Allenay FRIVILLE ESCARBOTIN 80019 Allery AIRAINES 80020 Allonville RIVERY 80021 Amiens voir sectorisation spécifique 80022 Andainville OISEMONT 80023 Andechy ROYE ANSENNES ( ratt. à BOUTTENCOURT) BLANGY SUR BRESLE (76) 80024 Argoeuves AMIENS Edouard Lucas 80025 Argoules CRECY EN PONTHIEU 80026 Arguel BEAUCAMPS LE VIEUX 80027 Armancourt ROYE 80028 Arquèves ACHEUX EN AMIENOIS 80029 Arrest ST VALERY SUR SOMME 80030 Arry RUE 80031 Arvillers MOREUIL 80032 Assainvillers MONTDIDIER 80033 Assevillers CHAULNES 80034 Athies HAM 80035 Aubercourt MOREUIL 80036 Aubigny CORBIE 80037 Aubvillers AILLY SUR NOYE 80038 Auchonvillers ALBERT PM Curie 80039 Ault MERS LES BAINS 80040 Aumâtre OISEMONT 80041 Aumont AIRAINES 80042 Autheux BERNAVILLE 80043 Authie ACHEUX EN AMIENOIS 80044 Authieule DOULLENS 80045 Authuille -

SE11 - Cimetière Militaire Du Commonwealth "Louvencourt Military Cemetery"

Association « Paysages et Sites de mémoire de la Grande Guerre » SE11 - Cimetière militaire du Commonwealth "Louvencourt Military Cemetery" Récapitulatif des attributs de l’élément constitutif Liste de l’ élément constitutif SE11 Cimetière - SE11 Cimetière militaire du Commonwealth et de leur(s) attribut(s) militaire du « Louvencourt Military Cemetery » majeur(s) Commonwealth « Louvencourt Military Cemetery » Eventuellement, liste de(s) Élément Aucun attribut(s) secondaire(s) constitutif Zone tampon Aucun Zone - SE03-i1 Basilique Notre-Dames de Brebières – Albert d’interprétation - SE04-i1 Cimetière militaire allemand - Fricourt - SE04-i2 Cairn au bataille McCrae - Contalmaison - SE04-i3 Mémorial canadien – Courcelette - SE04-i4 Site de l'ancien blockhaus-observatoire dit de « Gibraltar » - SE04-i5 Lochnagar crater - Ovillers-La Boisselle - SE11-i1 Forceville Communal Cemetery and Extension – Forceville Association « Paysages et Sites de mémoire de la Grande Guerre » ELEMENT CONSTITUTIF SE 11 ICONOGRAPHIE SE11- 001 Cimeti ère militair e du Comm onwea lth « Louv encour t Militar y Cemet ery © CD80 – F. Dourn el SE11-002 et SE-11-003 Stèles françaises et stèle de R. Leighton, du cimetière militaire du Commonwealth « Louvencourt Military Cemetery© CD80 – C. Calimez / F. Dournel Brève description textuelle des limites de l’élément constitutif Le « Louvencourt Military Cemetery » se situe sur le territoire communal de Louvencourt, au sud du village. Il longe la route communale reliant la commune de Louvencourt à celle de Léalvillers. Son environnement Association « Paysages et Sites de mémoire de la Grande Guerre » est rural et agraire. Au nord, un chemin enherbé permet l’acc ès piétonnier direct vers le centre du village. La position topographique du cimetière - surélevé par rapport à la route - lui permet de dominer le paysage agraire d’openfield qui s’étend vers l’ouest et le sud jusqu’à la crête qui lui fait face. -

Memorial Hospital (MH) and Parish Church (PC) Memorial Panels

THE GREAT WAR Cirencester Memorials Project Names on the Memorial Hospital (MH) and Parish Church (PC) Memorial Panels Name Death Regiment Cemetery/Memorial MH PC More Pict AGG, Alfred 1915 Mar 7 2 Glosters Ypres (Menin Gate) Mem P1WW1 C1 P1WW M ure AGG, John 1916 Jul 14 MGC Thiepval Mem P1 C1 P11 M P ALLAN, Frederick G 1918 Dec Somerset LI P1 C1 P1 M ALLAWAY, William J 1916 Sep 10 1 Glosters Heilly Station Cem P1 C1 P1 M ANDERSON, R Graham 1917 Nov 12 RGH Gaza War Cem P1 C1 P1 M P ANGELL, Walter 1917 Dec 5 5 Wilts P1 C1 P1 ANGELL, William 1918 Jun 7 7 KSLI Wimereux Communal Cem P1 C1 P1 M P BARRETT, James 1916 Nov 14 Essex Ciren Cem P1 C1 P1 M BARRETT, Richard E 1915 May 13 Royal Navy Chatham Naval Mem P1 C1 P1 M P BAXTER, Arthur 1916 Nov 13 7 RF Ancre British Cem P1 C1 P1 M BENNETT, Wilfred J 1917 Sep 20 20 AIF Ypres (Menin Gate) Mem P1 C1 P1 M BERRY, Albert 1918 May 15 1 Glosters Ciren Cem P1 C1 P1 M BERRY, Edward 1918 Apr 26 1 Wilts Tyne Cot Mem P1 C1 P1 M BILES, Ernest F 1917 Apr 5 1/5 Glosters Villers-Faucon Com Cem P1 C1 P1 M P BISHOP, Charles A 1916 Sep 6 Canadian Inf Vimy Mem P1 C1 P1 BISHOP, H W 1914 Nov 2 1 Somerset Ploegstreet Mem P1 C1 M P BISHOP, Horace E 1916 Jul 1 1/5 London Thiepval Mem P1 C1 P1 M BISHOP, James 1917 Nov 3 1 OBLI Baghdad War Mem P1 C1 P1 M BLACKWELL, Ernest G 1917? Jul 31 13 Glosters Duhallow ADS Cem P1 C1 P1 M P BLACKWELL, Martin W 1917 Feb 25 7 Glosters Basra Mem P1 C1 P1 M BLACKWELL, Reginald 1917 Apr 7 2/5 Glosters Vadencourt Brit Cem P1 C1 P1 M BOOTH, Frank 1916 Nov 18 8 Glosters Grandcourt Road Cem -

Circuit Du Festonval Toutencourt-Harponville

n°11 Circuit du Festonval Toutencourt-Harponville Durée : 3h00 Distance : 12,5 km Départ : Place du Ballon au poing au pied de la Croix de Toutencourt En venant d’Amiens: prendre la D919 et à la sortie de Contay tourner à gauche à la D23. En venant d’Albert, prendre la D91 vers Warloy-Baillon et à l’entrée de Contay tour- - 4886 conception : www.grandnord.fr ner à droite à la D23. Attention à vérifier les périodes de chasse 3 Après le cimetière, prendre à gauche le 6 Cette église aurait été construite avec en plaine. chemin herbeux pour rejoindre le bas les pierres de l’Abbaye de Clairfaye (pour du village. Au bout du chemin, à droite aller jusqu’à la motte castrale, emprun- 1 Départ sur la Place de Toutencourt, de- jusqu’au temple protestant. ter le chemin qui monte après l’église. vant la Croix. Cette croix, érigée au 15ème Un château au 11ème siècle aurait été siècle est classée Monument Historique 4 Sur le temple, regarder de près un re- construit en bois sur la butte, puis par depuis 1847. Prendre à droite, le «fossé» père d’altitude par rapport à la mer : la suite en pierre. Jusqu’au fossé, tou- face au café. A la sortie, prendre à droite vous êtes à 98m au dessus du niveau de tes les rues sont construites en arrondi (rue Terraine). Traverser le carrefour et à la mer ! Reprendre en direction de l’église autour de cette motte). Après l’église, 50m, prendre à droite rue de la Montagne.