£SRI LANKA @Unresolved "Disappearances" in the Period

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CHAP 9 Sri Lanka

79o 00' 79o 30' 80o 00' 80o 30' 81o 00' 81o 30' 82o 00' Kankesanturai Point Pedro A I Karaitivu I. Jana D Peninsula N Kayts Jana SRI LANKA I Palk Strait National capital Ja na Elephant Pass Punkudutivu I. Lag Provincial capital oon Devipattinam Delft I. Town, village Palk Bay Kilinochchi Provincial boundary - Puthukkudiyiruppu Nanthi Kadal Main road Rameswaram Iranaitivu Is. Mullaittivu Secondary road Pamban I. Ferry Vellankulam Dhanushkodi Talaimannar Manjulam Nayaru Lagoon Railroad A da m' Airport s Bridge NORTHERN Nedunkeni 9o 00' Kokkilai Lagoon Mannar I. Mannar Puliyankulam Pulmoddai Madhu Road Bay of Bengal Gulf of Mannar Silavatturai Vavuniya Nilaveli Pankulam Kebitigollewa Trincomalee Horuwupotana r Bay Medawachchiya diya A d o o o 8 30' ru 8 30' v K i A Karaitivu I. ru Hamillewa n a Mutur Y Pomparippu Anuradhapura Kantalai n o NORTH CENTRAL Kalpitiya o g Maragahewa a Kathiraveli L Kal m a Oy a a l a t t Puttalam Kekirawa Habarane u 8o 00' P Galgamuwa 8o 00' NORTH Polonnaruwa Dambula Valachchenai Anamaduwa a y O Mundal Maho a Chenkaladi Lake r u WESTERN d Batticaloa Naula a M uru ed D Ganewatta a EASTERN g n Madura Oya a G Reservoir Chilaw i l Maha Oya o Kurunegala e o 7 30' w 7 30' Matale a Paddiruppu h Kuliyapitiya a CENTRAL M Kehelula Kalmunai Pannala Kandy Mahiyangana Uhana Randenigale ya Amparai a O a Mah Reservoir y Negombo Kegalla O Gal Tirrukkovil Negombo Victoria Falls Reservoir Bibile Senanayake Lagoon Gampaha Samudra Ja-Ela o a Nuwara Badulla o 7 00' ng 7 00' Kelan a Avissawella Eliya Colombo i G Sri Jayewardenepura -

Divisional Secretariats Contact Details

Divisional Secretariats Contact Details District Divisional Secretariat Divisional Secretary Assistant Divisional Secretary Life Location Telephone Mobile Code Name E-mail Address Telephone Fax Name Telephone Mobile Number Name Number 5-2 Ampara Ampara Addalaichenai [email protected] Addalaichenai 0672277336 0672279213 J Liyakath Ali 0672055336 0778512717 0672277452 Mr.MAC.Ahamed Naseel 0779805066 Ampara Ampara [email protected] Divisional Secretariat, Dammarathana Road,Indrasarapura,Ampara 0632223435 0632223004 Mr.H.S.N. De Z.Siriwardana 0632223495 0718010121 063-2222351 Vacant Vacant Ampara Sammanthurai [email protected] Sammanthurai 0672260236 0672261124 Mr. S.L.M. Hanifa 0672260236 0716829843 0672260293 Mr.MM.Aseek 0777123453 Ampara Kalmunai (South) [email protected] Divisional Secretariat, Kalmunai 0672229236 0672229380 Mr.M.M.Nazeer 0672229236 0772710361 0672224430 Vacant - Ampara Padiyathalawa [email protected] Divisional Secretariat Padiyathalawa 0632246035 0632246190 R.M.N.Wijayathunga 0632246045 0718480734 0632050856 W.Wimansa Senewirathna 0712508960 Ampara Sainthamarathu [email protected] Main Street Sainthamaruthu 0672221890 0672221890 Mr. I.M.Rikas 0752800852 0672056490 I.M Rikas 0777994493 Ampara Dehiattakandiya [email protected] Divisional Secretariat, Dehiattakandiya. 027-2250167 027-2250197 Mr.R.M.N.C.Hemakumara 027-2250177 0701287125 027-2250081 Mr.S.Partheepan 0714314324 Ampara Navithanvelly [email protected] Divisional secretariat, Navithanveli, Amparai 0672224580 0672223256 MR S.RANGANATHAN 0672223256 0776701027 0672056885 MR N.NAVANEETHARAJAH 0777065410 0718430744/0 Ampara Akkaraipattu [email protected] Main Street, Divisional Secretariat- Akkaraipattu 067 22 77 380 067 22 800 41 M.S.Mohmaed Razzan 067 2277236 765527050 - Mrs. A.K. Roshin Thaj 774659595 Ampara Ninthavur Nintavur Main Street, Nintavur 0672250036 0672250036 Mr. T.M.M. -

Tides of Violence: Mapping the Sri Lankan Conflict from 1983 to 2009 About the Public Interest Advocacy Centre

Tides of violence: mapping the Sri Lankan conflict from 1983 to 2009 About the Public Interest Advocacy Centre The Public Interest Advocacy Centre (PIAC) is an independent, non-profit legal centre based in Sydney. Established in 1982, PIAC tackles barriers to justice and fairness experienced by people who are vulnerable or facing disadvantage. We ensure basic rights are enjoyed across the community through legal assistance and strategic litigation, public policy development, communication and training. 2nd edition May 2019 Contact: Public Interest Advocacy Centre Level 5, 175 Liverpool St Sydney NSW 2000 Website: www.piac.asn.au Public Interest Advocacy Centre @PIACnews The Public Interest Advocacy Centre office is located on the land of the Gadigal of the Eora Nation. TIDES OF VIOLENCE: MAPPING THE SRI LANKAN CONFLICT FROM 1983 TO 2009 03 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ....................................................................................................................... 09 Background to CMAP .............................................................................................................................................09 Report overview .......................................................................................................................................................09 Key violation patterns in each time period ......................................................................................................09 24 July 1983 – 28 July 1987 .................................................................................................................................10 -

Urban Development Plan

Urban Development Plan (2018 – 2030) Urban Development Authority Sabaragamuwa Province Volume 01 RATNAPURA DEVELOPMENT PLAN VOLUME I Urban Development Authority “Sethsiripaya” Battaramulla 2018 - 2030 RATNAPURA DEVELOPMENT PLAN VOLUME I Urban Development Authority 2018 - 2030 Minister’s Foreword Local Authority Chairman’s Forward DOCUMENT INFORMATION Report Title : Ratnapura Development Plan Locational Boundary (Declared area) : Ratnapura Municipal Council Area Gazette No : Client / Stakeholder (Shortly) : Local residents of Ratnapura, Relevant Institutions, Commuters. Submission Date : 17/12/2018 Document Status : Final Document Submission Details Author UDA Ratnapura District Office Version No Details Date of Submission Approved for Issue 1 English Draft 07/12/2018 2 English Final 07/01/2019 This document is issued for the party which commissioned it and for specific purposes connected with the above-captioned project only. It should not be relied upon by any other party or used for any other purpose. We accept no responsibility for the consequences of this document being relied upon by any other party, or being used for any other purpose, or containing any error or omission which is due to an error or omission in data supplied to us by other parties. This document contains confidential information and proprietary intellectual property. It should not be shown to other parties without consent from the party which commissioned it. Preface This development plan has been prepared for the implementation of the development of Ratnapura Municipal Council area within next two decades. Ratnapura town is the capital of the Ratnapura District. The Ratnapura town has a population of approximately 49,083 and act as a regional center servicing the surrounding hinterland area and providing major services including administration, education and health. -

The State (The Embilipitiya Abduction and Murder Case)

362 Sri Lanka Law Reports [2003] 3 Sri l... DAYANANDA LOKUGALAPPATHTHI AND EIGHT OTHERS v THE STATE (THE EMBILIPITIYA ABDUCTION AND MURDER CASE) COURT OF APPEAL KULATILAKA, J. FERNANDO, J. C .A .9 3 -9 9 H.C.RATNAPURA 121/94 MAY 2,28,29,2001 JUNE 11,12,18,19,25,26, 2001 - JULY 2,3,9,10,17,18,31,2001 AUGUST 2,27,29,2001 SEPTEMBER 3,4,5,10,11,12,17,19,24,25,26,2001 OCTOBER 23,24,25,30,2001 NOVEMBER 5,6,7,12,13,19,20,21,22,26,27,28,29,200 i DECEMBER 3,7,10,11,12,2001 Penal Code - Sections 32 - 113(A), 113(b), 334, 335, 353 and 356 - Evidence Ordinance - Sections 3, 10, 11, 106 and 134 - Code of Criminal Procedure - Sections 217, 229 and 232 - Conspiracy, Abduction - Aiding and Abetting - wrongful confinement - Murder - Is intention a necessary ingredient? - Proof? - Is the offence of abduction a continuing offence?- Corroborative evidence - Dock identification -Test of spontaneity and contemporaneity - Test of Probability and - Improbability - Common intention - Applicability of section 217 Criminal Procedure Code to trial by a Judge of the High Court - Alibi - Nemo Allegans Suam Turpitudinem non audiendus est. Dayananda Lokugalappaththi and eight others v The State CA (The Embilipitiya Abduction and Murder Case) (Kulatilaka, J.) 3 6 3 In the prosecution before the High Court sitting without a jury nine accused were indicted on a total of 80 counts. Count Nos.1-4 - related to all accused to wit: Count 1 and 3 - Conspiracy to commit acts of abduction or aiding and abetting to abduct in order to secretly and wrongfully confine certain unidentified persons and in order to commit murder. -

Classic Sri Lanka

Classic Sri Lanka Classic Sri Lanka 9 Days | Starts/Ends: Colombo PRIVATE TOUR: Exotic Sri Lanka, • 8 nights SUPERIOR hotels. STANDARD Day 2 : Sightseeing in ancient cities steeped in history, and DELUXE hotel options are also Colombo available upon request. Accommodation elephants, tea plantations, lush Today, your guide will take you on a driving rating – See Trip Notes for details countryside, bustling bazaars and tour around colourful Colombo, Sri Lanka's • Touring - Colombo, Dambulla, frenetic capital. Just off the north end of wildlife, Sri Lanka has all this and Polonnaruwa, Sigariya, Matale, Kandy, Galle Road, the main north-south artery of more. Enjoy a wonderful 9 day Nuwara Eliya and Udawalawe NP the city is the area known as the Fort, once • Jeep safari/game drive in Udawalawe holiday taking in the highlights of a colonial stronghold but now the site of National park this enchanting island. many government buildings and interesting • Escorted by a licensed English speaking shops. Just south of the Fort is Galle Face chauffeur guide HIGHLIGHTS AND INCLUSIONS Green, a seaside expanse where informal • An airport arrival transfer day 1 and a cricket games are played out amongst city departure transfer day 9 Trip Highlights folk enjoying a pleasant stroll. At the south • All transfers and transportation in private end of the green is the Galle Face Hotel, a • Polonnaruwa - 11th century city air-conditioned tourism vehicles beautiful colonial-era hotel. Just east of the • Sigiriya - Spectacular 5th century fortress • Specialist local guides at some sites Fort is the Pettah, the traditional bazaar district ruins • Entrance fees to all included sites – a colourful retail experience. -

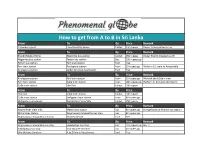

How to Get from a to B in Sri Lanka

How to get from A to B in Sri Lanka From To By Price Remark Colombo airport Erandi Holiday Home tuktuk 250 rupees Owner Erandi picked us up From To By Price Remark Erandi Holiday Home Negombo bus station tuktuk 250 rupees Owner Erandi dropped us off Negombo bus station Pettah bus station Bus 200 rupees pp Pettah bus station Fort train station foot free Fort train station Kirulapona station train 10 rupees pp Platform 10, train to Avissawella Kirulapona station Siebel Serviced Apartments foot free From To By Price Remark Kirulapona station Fort train station train 10 rupees pp We took the 8.10am train Fort train station Galle train station train 180 rupees pp Platform 5, 2nd class (10.30am) Galle train station The One tuktuk 100 rupees From To By Price Remark The One Galle train station tuktuk 100 rupees Galle train station Weligama train station train 60 rupees pp Weligama train station Naomi River View Villa tuktuk 150 rupees From To By Price Remark Naomi River View Villa Matara bus station bus 50 rupees pp change buses at Matara bus station Matara bus station Wajirawansa Maawatha bus stop bus 50 rupees pp Wajirawansa Maawatha bus stop Seaview Resort foot free From To By Price Remark Wajirawansa Maawatha bus stop Embilipitiya bus stop bus 110 rupees pp Bus 11 Embilipitiya bus stop Uda Walawe Junction bus 50 rupees pp Uda Walawe Junction A to Z Family Guesthouse foot free How to get from A to B in Sri Lanka From To By Price Remark Uda Walawe Junction Welawaya bus station bus 100 rupees pp Bus 98 Welawaya bus station Ella (bus stop is -

Efficiency Bar Examination for Grade I Samurdhi Development Officers at Samurdhi Authority of Sri Lanka - 2009(2011)

EFFICIENCY BAR EXAMINATION FOR GRADE I SAMURDHI DEVELOPMENT OFFICERS AT SAMURDHI AUTHORITY OF SRI LANKA - 2009(2011) (Grade I ) Results >=40 then " PASS" INDEX NAME ADDRESS1 ADDRESS2 SEX MEDIUM SUB1 MK SUB2 MK NO 1000012 THILAKAWARDANA, K.D.I. 336, SUMAGA, GANEWATTA ROAD, MAMPE, PILIYANDALA. FEMALE SINHALA 044 --- 1000020 NILANI, H.M. 113/3, MAHARAGAMA ROAD, MAWITTARA, PILIYANDALA. FEMALE SINHALA 047 --- 1000039 SANDAMALI, M.D.P. 120/4, P.S. PERERA MAWATHA, MAMPE, PILIYANDALA. FEMALE SINHALA 040 --- 1000047 HETTIARACHCHI, P.D. 1070/2, DENSIL KOBBAKADUWA MAWATHA, BATTARAMULLA. FEMALE SINHALA 040 --- SAMURDI AUTHORITY,ESTABISHMENT DIV. 4TH 1000055 MANEL, M.A.P. BATTARAMULLA. FEMALE SINHALA 055 --- FLOOR, SETHSIRIPAYA, 1000063 RASHADARI, W.A.D.A. 92/A, SUDARSHANA MAWATHA, MAKANDANA, MADAPATHA. FEMALE SINHALA 029 --- 1000071 DEEPANI, A.A. 209/3, POLWATTA ROAD, PAMUNUWA, MAHARAGAMA. FEMALE SINHALA 041 --- 1000080 DEEPIKA, A.P. 247, MEEGAHAWATTA, KANAMPELLA, KOSGAMA. FEMALE SINHALA ABS --- 1000098 PATHIRAGE, D.S.U. 728/4, MADAWALA ROAD, ERAWWALA, PANNIPITIYA. FEMALE SINHALA ABS --- 1000101 CHITHRA, B.P.A. 1183/23, MARADANA ROAD, BORELLA, COLOMBO 8. FEMALE SINHALA 031 --- 1000110 HAPUTHANTHRI, H.S.P. 47, MAHINGALA, BOPE, PADUKKA. MALE SINHALA 040 --- 1000128 PIYASEELI, G. 228, HORAGALA WEST, PADUKKA. FEMALE SINHALA ABS --- 1000136 PERERA, P.K.V. 418/8, SEA BEACH ROAD, ANGULANA, MORATUWA. MALE SINHALA 040 --- 1000144 GUNAWARDENA, T.T.W.K. 176/4, W.A. SILVA MAWATHA, PAMANKADA, COLOMBO 6. FEMALE SINHALA 040 --- 1000152 SANJEEVANI, P. 12/D/1, KUDAKANDA, THUNNANA, HANWELLA. FEMALE SINHALA ABS --- 1000160 NAWARATHNA, D.L. 11/5, MAHAJANA ROAD, KADALANA, MORATUWA. FEMALE SINHALA 043 --- 1000179 HEMALI, M.A.C. DIVISIONAL SECRETARIAT, KOLONNAWA. -

List of 1000 Secondary Schools - Sabaragamuwa Schools Secondary Province 1000 of List Name Ofname School Halwinna, Godakawela

LIST OF 1000 SECONDARY SCHOOLS - SABARAGAMUWA PROVINCE NO. OF STUDENTS EDUCATION S/N NAME OF SCHOOL ADDRESS TEL. NO. ZONE NO. OF TEACHERS 1-5 6-11 12-13 TOTAL 1 BALANGODA ANANDA MAITHRIYA M.M.V. BALANGODA. 0452287191 0 1660 1368 3028 143 2 BALANGODA JEILANI MUSLIM M.V. DEHIGASTALAWA, BALANGODA. 0452287185 0 631 213 844 42 3 BALANGODA KANAGANAYAGAM T.M.V. RASSAGALA ROAD , BALANGODA. 104 537 48 689 33 4 BALANGODA SRI NARADA M.V. WIKILIYA, BALANGODA. 0452288238 54 413 129 596 48 5 BALANGODA VIDYALOKA M.V. OLD ROAD, BALANGODA. 0452286206 0 933 153 1086 67 6 BALANGODA WELIPATHAYAYA M.V. WELIPATHAYAYA, BALANGODA. 0455738008 64 199 44 307 23 7 BALANGODA KARAGASTHALAWA M.V. KARAGASTHALAWA, BELIHULOYA. 0 353 98 451 38 8 BALANGODA UDAGAMA M.V. PINNAWALA, BALANGODA. 0452050553 0 1047 462 1509 74 9 BALANGODA SRI WAJIRAWANSHA M.V. AMBEWILA, PALLEBEDDA. 0452241528 402 332 74 808 43 10 BALANGODA SRI WALAGMBA M.V. WELIGEPOLA, BALANGODA. 0 402 124 526 38 11 BALANGODA UDAWELA M.V. OPANAYAKA. 0453453937 0 204 32 236 20 12 BALANGODA VIDYAKARA M.V. OPANAYAKA. 0452270390 0 651 178 829 49 13 EMBILIPITIYA CHANDRIKAWEWA JAYANTHI M.V. 42, PADALANGALA. 0 972 243 1215 61 14 EMBILIPITIYA COLOMBAGEARA M.V. COLOMBAGEARA. 0472232271 0 848 150 998 56 15 EMBILIPITIYA PANAMURA M.V. PANAMURA. 0473470915 0 423 76 499 30 16 EMBILIPITIYA PRESIDENT'S COLLEGE NEW TOWN, EMBILIPITIYA. 0472230310 1786 2533 870 5189 220 17 EMBILIPITIYA KULARATHNA M.M.V. GODAKAWELA. 0452240313 0 1140 354 1494 81 18 EMBILIPITIYA RAHULA M.M.V. GODAKAWELA. -

5000-Schools-Funded-By-The-Ministry

5000 Schools developed as Child Frendly Schools by funding Rs 500,000.00 by Economic Development Ministry to develop infastructure Province District Name of School Address Education Zone Education Division 1 Western Colombo SRI SANGAMITTA P.V. 62,ANANDA RAJAKARUNA MW.,COL-09 Colombo Borella 2 Western Colombo SUJATHA B.V. KIRIMANDALA MW.,COL-05 Colombo Colombo - South 3 Western Colombo LUMBINI P.V. HAVELOCK TOWN,COL-05. Colombo Colombo - South 4 Western Colombo ST.CLARE'S B.M.V. 1SR CHAPEL LANE,COL-06. Colombo Colombo - South 5 Western Colombo THANNINAYAGAM T.V. LESLEY RANAGALA MW.,COL-08 Colombo Borella 6 Western Colombo SIR BARON JAYATHILAKA V. MALIGAWATTA,COL-10. Colombo Colombo - Central 7 Western Colombo MIHINDU MAWATHA SINHALA V. MIHINDU MAWATHA,COLOMBO 12. Colombo Colombo - Central 8 Western Colombo ROMAN CATHOLIC V. KOTIKAWATTA, MULLERIYAWA NEW TOWN. Sri Jaya' pura Kolonnawa 9 Western Colombo MEETHOTAMULLA SRI RAHULA V. MEETHOTAMULLA, KOLONNAWA. Sri Jaya' pura Kolonnawa 10 Western Colombo KOTUWILA GAMINI V. KOTUWILA, WELLAMPITIYA. Sri Jaya' pura Kolonnawa 11 Western Colombo WERAGODA K.V. KOLONNAWA, WELLAMPITIYA. Sri Jaya' pura Kolonnawa 12 Western Colombo GOTHATUWA M.V. GOTHATUWA, ANGODA. Sri Jaya' pura Kolonnawa 13 Western Colombo VIDYAWARDENA V. WELLAMPITIYA, KOLONNAWA. Sri Jaya' pura Kolonnawa 14 Western Colombo SUGATHADHARMADHARA V. EGODAUYANA, MORATUWA Piliyandala Moratuwa 15 Western Colombo KATUKURUNDA ST MARY'S V. KATUKURUNDA, MORATUWA Piliyandala Moratuwa 16 Western Colombo SRI SADDARMODAYA V. KORALAWELLA MORATUWA Piliyandala Moratuwa 17 Western Colombo SRI NAGASENA V. KORAWELLA, MORATUWA Piliyandala Moratuwa 18 Western Colombo PITIPANA K.V. PITIPANA NORTH, HOMAGAMA. Homagama Homagama 19 Western Colombo DOLAHENA K.V. -

Levi Strauss & Co. Factory List

Levi Strauss & Co. Factory List Published : November 2019 Total Number of LS&Co. Parent Company Name Employees Country Factory name Alternative Name Address City State Product Type (TOE) Initiatives (Licensee factories are (Workers, Staff, (WWB) blank) Contract Staff) Argentina Accecuer SA Juan Zanella 4656 Caseros Accessories <1000 Capital Argentina Best Sox S.A. Charlone 1446 Federal Apparel <1000 Argentina Estex Argentina S.R.L. Superi, 3530 Caba Apparel <1000 Argentina Gitti SRL Italia 4043 Mar del Plata Apparel <1000 Argentina Manufactura Arrecifes S.A. Ruta Nacional 8, Kilometro 178 Arrecifes Apparel <1000 Argentina Procesadora Serviconf SRL Gobernardor Ramon Castro 4765 Vicente Lopez Apparel <1000 Capital Argentina Spring S.R.L. Darwin, 173 Federal Apparel <1000 Asamblea (101) #536, Villa Lynch Argentina TEXINTER S.A. Texinter S.A. B1672AIB, Buenos Aires Buenos Aires <1000 Argentina Underwear M&S, S.R.L Levalle 449 Avellaneda Apparel <1000 Argentina Vira Offis S.A. Virasoro, 3570 Rosario Apparel <1000 Plot # 246-249, Shiddirgonj, Bangladesh Ananta Apparels Ltd. Nazmul Hoque Narayangonj-1431 Narayangonj Apparel 1000-5000 WWB Ananta KASHPARA, NOYABARI, Bangladesh Ananta Denim Technology Ltd. Mr. Zakaria Habib Tanzil KANCHPUR Narayanganj Apparel 1000-5000 WWB Ananta Ayesha Clothing Company Ltd (Ayesha Bangobandhu Road, Tongabari, Clothing Company Ltd,Hamza Trims Ltd, Gazirchat Alia Madrasha, Ashulia, Bangladesh Hamza Clothing Ltd) Ayesha Clothing Company Ltd( Dhaka Dhaka Apparel 1000-5000 Jamgora, Post Office : Gazirchat Ayesha Clothing Company Ltd (Ayesha Ayesha Clothing Company Ltd(Unit-1)d Alia Madrasha, P.S : Savar, Bangladesh Washing Ltd.) (Ayesha Washing Ltd) Dhaka Dhaka Apparel 1000-5000 Khejur Bagan, Bara Ashulia, Bangladesh Cosmopolitan Industries PVT Ltd CIPL Savar Dhaka Apparel 1000-5000 WWB Epic Designers Ltd 1612, South Salna, Salna Bazar, Bangladesh Cutting Edge Industries Ltd. -

Manpower Pvt Ltd 114320544 G Enterprise Rentals Pvt Ltd

TIN Name 114440175 AMIRO INVEST: SECUR: & MANPOWER PVT LTD 114320544 G ENTERPRISE RENTALS PVT LTD 422251464 GUNAWARDHANA W K J 693630126 INDUKA K B A 722623517 JANATH RAVINDRA W P M 673371825 NUGEGODA M B 291591310 RATHNAYAKE W N 537192461 SITHY PATHUMMA M H MRS 409248160 STAR ENTERPRISES 568003977 WEERASINGHE L D A 134009080 1 2 4 DESIGNS LTD 114287954 21ST CENTURY INTERIORS PVT LTD 409327150 3 C HOLDINGS 174814414 3 DIAMOND HOLDINGS PVT LTD 114689491 3 FA MANAGEMENT SERVICES PVT LTD 114458643 3 MIX PVT LTD 114234281 3 S CONCEPT PVT LTD 409084141 3 S ENTERPRISE 114689092 3 S PANORAMA HOLDINGS PVT LTD 409243622 3 S PRINT SOLUTION 114488151 3 WAY FREIGHT INTERNATIONAL PVT LTD 114707570 3 WHEEL LANKA AUTO TECH PVT LTD 409086896 3D COMPUTING TECHNOLOGIES 409248764 3D PACKAGING SERVICE 409088198 3S INTERNATIONAL MARKETING PVT CO 114251461 3W INNOVATIONS PVT LTD 672581214 4 X 4 MOTORS 114372706 4M PRODUCTS & SERVICES PVT LTD 409206760 4U OFFSET PRINTERS 114102890 505 APPAREL'S PVT LTD 114072079 505 MOTORS PVT LTD 409150578 555 EGODAGE ENVIR;FRENDLY MANU;& EXPORTS 114265780 609 PACKAGING PVT LTD 114333646 609 POLYMER EXPORTS PVT LTD 409115292 6-7BHATHIYAGAMA GRAMASANWARDENA SAMITIYA 114337200 7TH GEAR PVT LTD 114205052 9.4.MOTORS PVT LTD 409274935 A & A ADVERTISING 409096590 A & A CONSTRUCTION 409018165 A & A ENTERPRISES 114456560 A & A ENTERPRISES FIRE PROTECTION PVT LT 409208711 A & A GRAPHICS 114211524 A & A HOLDINGS PVT LTD 114610569 A & A TECHNOLOGY PVT LTD 114480860 A & A TELECOMMUNICATION ENG;SER;PVT LTD 409118887 A & B ENTERPRISES 114268410