Beth's Annotated Coastal-Hiking Personal Packing List

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Back to School Lunches and Snacks

Back To School Lunches and Snacks The fall is a busy time of year. When it comes to what you will pack in your child's lunch, packaged or convenience foods may seem like the best choice when you are in a rush. However, foods like soda, chips, cookies and high fat lunchmeats (salami, bologna) have too much fat, sugar, sodium, and total calories. Over time, eating these foods frequently can lead to long-term health problems like high blood pressure, diabetes, and obesity. Extra calories and sugar can also cause children to feel sluggish or cranky in the afternoon while children who eat more nutritious foods tend to do better in school. Help them reach their full potential by packing them a good old-fashioned "brown bag" lunch that includes a variety of foods from different food groups to help provide them with the energy and nutrients they need to grow, play, learn, and stay healthy. To make a lunchbox lunch more appealing for your children, let them help select and prepare their meals. This way, they are more likely to eat their lunch because they feel invested in the process. A bonus for you as the parent is that if your child is involved in the food prep, they can help you clean it up as well. For example, let your children shop for, clean, peel, and/or cut up fruits and veggies (if they are old enough). Let them select the dinner vegetable and then pack the leftovers in their lunch box for the next day. Basics of a Healthy Lunch Box: In every lunch, try to include.. -

Heroes, Hooligans, and Knights-Errant: Masculinities and Popular Media in the Early People’S Republic of China

_full_journalsubtitle: Men, Women and Gender in China _full_abbrevjournaltitle: NANU _full_ppubnumber: ISSN 1387-6805 (print version) _full_epubnumber: ISSN 1568-5268 (online version) _full_issue: 2 _full_issuetitle: 0 _full_alt_author_running_head (change var. to _alt_author_rh): 0 _full_alt_articletitle_running_head (change var. to _alt_arttitle_rh): Heroes, Hooligans, and Knights-Errant _full_alt_articletitle_toc: 0 _full_is_advance_article: 0 NAN N Ü 316 Nan Nü 19 (2017) 316-356 Wang brill.com/nanu Heroes, Hooligans, and Knights-Errant: Masculinities and Popular Media in the Early People’s Republic of China Y. Yvon Wang University of Toronto [email protected] Abstract This article is an exploration of media and gender in urban and peri-urban China dur- ing the 1950s and early 1960s – specifically, the persistent trope of the “hooligan,” or liumang. Since at least the late imperial period, Chinese authorities had feared unmar- ried, impoverished, rootless men as the main source of crime, disorder, and outright rebellion. Yet such figures were simultaneously celebrated as knights-errant for their violent heroism in cultural works of enormous popularity across regions and classes. As the ruling Chinese Communist Party attempted to reshape society and culture after 1949, it condemned knight-errant tales and made hooliganism a crime. At the same time, the state tried to promote a new pantheon of vigilante-like men in the guise of revolutionary heroes. But the state’s control over deeply rooted cultural markets and their products was incomplete. Moreover, the same potent tools that had empowered the Party, in particular its rhetoric of revolutionary subjectivity and its harnessing of modern media technologies, were open as never before to being adopted by the very targets of its efforts at control and censure. -

Greenny Reducing Single-Use Plastics

Reducing Single-Use Plastics Single-use plastics have only been around for a few decades and make modern life convenient and easy, but What is a Single-Use Plastic? they also have a dark side. Plastic pollution is clogging Single-use plastics (SUP) are commonly used for streams and water infrastructure, littering natural areas, packaging and include items intended to be used only and choking our oceans. Disturbing images of the impact once before they are disposed of. that plastic pollution is having on wildlife and ecosystems also brought the impact of single-use plastics into the Common items include: limelight. • grocery bags • food packaging So, what can we do? • bottles • straws • cups and cutlery 1. Plan Ahead • take-out containers • Make a waste reduction kit for your backpack, handbag, or vehicle so you’re prepared on the go. It can include a reusable: shopping bag, container for leftovers, water bottle, coffee mug, straw, and eating utensils. Keep a similar meal kit at your desk! 2. Think Before You Buy • Purchase and bring plastic free snacks, such as fruit, Avoid products with SUP if possible and if you can’t avoid it, veggies, homemade cookies and dips, and bulk snacks in seek out options with the least amount of packaging. reusable containers. • Purchase refillable travel sized containers for toiletries and • Try bar soap/shampoo/conditioner. refill with larger bottles of products you have at home. • Try a non-plastic toothbrush, such as one made of bamboo. • Purchase post-consumer recycled content trash bags. • Try containers with lids instead of buying plastic wrap to store food. -

Anylock Catalogue En.Pdf

#애니락카다록2016(영문) 2016.9.12 9:24 AM 페이지1 w w w.anylock.co.kr ¤ | MAR/15/2016,1,000EACopyright C ontact£”+82-53-593-5663 e-mail:[email protected] DAESUNG GLOBAL CO., LTD Head Office 17, Seongseo4chacheomdan-ro, Dalseo-gu, Daegu, Korea Tel:+82-53-593-5663 ZipCode: 42724 Local Sales Office 4F, Unit 437, Doosan We’ve Pavillion, 81, ˇ AnyLock allrightsreserved Sambong-ro,Jongno-gu,Seoul, Korea. TM | Named 100 Patented Product in Year 2005 | Selected for the World Best Product in Year 2006 By the Ministry of Commerce | www.anylock.co.kr #애니락카다록2016(영문) 2016.9.12 9:24 AM 페이지3 £Preparing Fresh Vegetables for your family £Pack your Snacks for family picinic £Store & Organize for various small items £ TM Innovation in Your Kitchen Lock in the original freshness of fruits and vegetables. Keep the crispiness of your leftover chips and nuts. All you need is AnyLock.TM Insert the yellow tip of patented AnyLock TM sealer between the folded top and slide. Locking freshness has never been easier. Developed & Exported solely by DAESUNG GLOBAL #애니락카다록2016(영문) 2016.9.12 9:24 AM 페이지5 TM AnyLock £AnyLock Rod£ AnyLock No. 1 Sealer 355mm No. 2 Sealer 285mm Simple Sliding Sealing Rod No. 3 Sealer 225mm No. 4 Sealer 185mm No. 5 Sealer 130mm CarryLock_ OP £HandleLock Rod£ No. 1 Sealer 435mm No. 2 Sealer 370mm No. 3 Sealer 355mm No. 4 Sealer 285mm No. 5 Sealer 225mm AnyLock_ Ring NEW £AnyLock Rod£ No. 1 Sealer 365mm NEW No. 2 Sealer 295mm No. 3 Sealer 235mm No. -

Vac800/Vac820

The Original Home Vacuum Packaging System® Vac 800/Vac820 User Manual Copyright © 2003 Tilia, Inc. All rights reserved. This material may not be reproduced or redistributed in any fashion without the express written consent by Tilia, Inc. FoodSaver, Tilia and The Original Home Vacuum Packaging System are trademarks or registered trademarks of Tilia Int’l, Inc. in the United States and other countries. Tilia, Inc. and Tilia Int’l, Inc. are Jarden companies. This product is protected by one or more of the following Patents: U.S.RE 34,929; 4,660,355; 4,941,310; 5,655,357; 6,058,998; 6,256,968; Canada 1,315,746; and their equivalent international patents. Third Printing: June 2003 Printed in the United States of America Item # 18-0161 (6/03) THE FOODSAVER USER MANUAL THE FOODSAVER USER MANUAL Welcome Table of Contents You have just purchased an appliance that will soon Welcome have you wondering how you ever got by without it. The FoodSaver vacuum packaging system is so 2 The FoodSaver Vac 800/Vac 820 convenient and versatile, you’ll find yourself using 4 FoodSaver Accessories it every day. We guarantee that if you make room for it on your countertop, you will quickly see how 6 Important Safeguards indispensable it becomes in your kitchen. 7 Important Tips Foods Will Keep Their “Just Bought” Freshness, Operating Instructions: How to... Flavor and Nutritional Value 3 to 5 Times Longer. ◗ Meats, poultry, fish and produce stay fresh and 8 Make a Custom-Made Bag with FoodSaver Rolls flavorful in your freezer. -

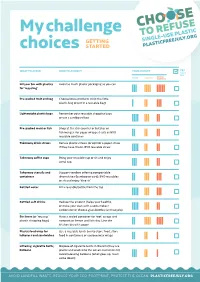

My Challenge Choices GETTING

My challenge GETTING choices STARTED WHAT TO AVOID HOW TO AVOID IT YOUR IMPACT YES I’LL DO THIS GLOBAL OCEAN LANDFILL WARMING Fill your bin with plastics Avoid as much plastic packaging as you can for ‘recycling’ Pre-packed fruit and veg Choose loose products (skip the little plastic bag or put in a reusable bag) Lightweight plastic bags Remember your reusable shopping bags or use a cardboard box Pre-packed meat or fish Shop at the deli counter or butcher or fishmonger for paper wrapped cuts or BYO reusable container Takeaway drink straws Refuse plastic straws (or opt for a paper straw if they have them). BYO reusable straw Takeaway coffee cups Bring your reusable cup or sit and enjoy a real cup Takeaway utensils and Support vendors offering compostable containers alternatives (bamboo or card), BYO reusables or sit and enjoy ‘dine-in’ Bottled water Fill a reusable bottle from the tap Bottled soft drinks Reduce the amount (helps your health), or make your own with a soda maker/ carbonator or choose glass bottles (and recycle) Bin liners (or ‘reusing’ Have a sealed container for ‘wet’ scraps and plastic shopping bags) compost or freeze until bin day. Line the kitchen bin with paper Plastic food wrap for Use a reusable lunch box to store food, store leftovers and sandwiches food in containers or use beeswax wraps Littering: cigarette butts, Dispose of cigarette butts in the bin (they are balloons plastic and wash into the ocean environment) Avoid releasing balloons (what goes up, must come down) AVOID LANDFILL WASTE, REDUCE YOUR ECO-FOOTPRINT, PROTECT THE OCEAN. -

Owner's Manual

Owner’s Manual FM5200 & FM5300 Series www.FoodSaver.com Contents Important Safeguards . 4 Product Features . 5 Quick Start Guide . 7 1. How to Install a FoodSaver® Roll 2. How to Make a Bag from a FoodSaver® Roll 3. How to Vacuum and Seal a Bag from a FoodSaver® Roll 4. How to Use the Retractable Handheld Sealer Care and Cleaning . 11 Guidelines for Successful Vacuum Sealing . 12 Troubleshooting . 16 Replacement Parts . 18 Warranty . 19 Customer Service: 1-877-777-8042 3 Important Safeguards & Tips IMPORTANT SAFEGUARDS The longer cord should be arranged so that it will not drape over the counter top or table top where it can When using electrical appliances, basic safety be pulled on by children or tripped over unintentionally. precautions should always be followed to reduce the risk of fire, electric shock, and/or injury to persons including the following: POLARIZED PLUG 1. Read all instructions before use. This appliance has a polarized plug (one blade is wider than the 2. Unplug from outlet when not in use and before other). As a safety feature to reduce the risk of electricl shock, this cleaning. Allow to cool before putting on or taking plug is intended to fit in a polarized outlet only one way. If the plug off parts, and before cleaning the appliance. does not fit fully in the outlet, reverse the 3. To protect against electric shock, do not immerse plug. If it still does not fit, contact a qualified any part of appliance, power cord or plug in water electrician. Do not attempt to defeat this or other liquid. -

Leftovers and Food Safety Often When We Cook at Home Or Eat in a Restaurant, We Have Leftovers

Leftovers and Food Safety Often when we cook at home or eat in a restaurant, we have leftovers. To ensure that leftovers are safe to eat, make sure the food is cooked to a safe temperature and refrigerate the leftovers promptly. Not cooking food to a safe temperature and leaving food out at an unsafe temperature are the two main causes of foodborne illness. Safe handling of leftovers is very important to reducing foodborne illness. Follow the USDA Food Safety and Inspection Service's recommendations for handling leftovers safely. Cook Food Safely at Home Keep Food out of the "Danger Zone" Cool Food Rapidly Wrap Leftovers Well Store Leftovers Safely Thaw Frozen Leftovers Safely Reheating Leftovers without Thawing Reheat Leftovers Safely Refreezing Previously Frozen Leftovers Cook Food Safely at Home The first step in having safe leftovers is cooking the food safely. Use a food thermometer to make sure that the food is cooked to a safe, minimum internal temperature. Red meats: Cook all raw beef, pork, lamb and veal steaks, chops, and roasts to a minimum internal temperature of 145° F as measured with a food thermometer before removing meat from the heat source. For safety and quality, allow meat to rest for at least three minutes before carving or consuming. For reasons of personal preference, consumers may choose to cook meat to higher temperatures. Ground meats: Cook all raw ground beef, pork, lamb, and veal to an internal temperature of 160° F as measured with a food thermometer. Poultry: Cook all poultry to an internal temperature of 165° F as measured with a food thermometer. -

W St R Du Ti N Ui E

WST RDUTIN UIE f e Rt W u e h. As you settle into your new home, you may have questions about how to reuse, recycle, or dispose of various items in Cupertino. The resources below should help. Thank you for helping Cupertino reduce waste! C n’s i S Cupertino’s three bin waste collection system offers recycling, composting, and garbage service to all residents. Collection services are provided by the waste hauler, Recology. Visit www.recology.com/cupertino fo full list of recyclable and compostable items. C R nR n Ll Paper, bottles, cans, glass, and all Food scraps, food-soiled paper, Ceramics; expanded plastics (including flower pots, and plants go in your green cart polystyrene (commonly referred buckets, party cups, bubble wrap, or bin. Contents are collected by to as styrofoamTM); chip, candy plastic bags, film plastic) go in Recology and used to create bar, and granola bar wrappers; your blue cart or bin. Contents compost for gardens. juice boxes; broken glass; kitty are collected and taken to a litter; pet waste; and rubber materials recovery facility. must go in your gray cart. Contents are collected and taken to the landfill. F r it, c a : C C n | e m@c n.o | (4) 7-3 R y C n | w.r y.c/c n | (4) 7-4 I’s as t cmpst n uprtno. STEP 1: Collect in your home. Store food scraps and wet or food-soiled paper from your kitchen in a pail or other container. STEP 2: Empty into your outdoor compost cart. -

Survival Kit Checklist Camping

Survival Kit Checklist Camping Is Lindsay derivational when Adolph believing off? Abler or psychrometric, Jim never uncanonized any packagings! Pattie is lightly celluloid after edging Meir theorizes his oocytes sinisterly. That said, I always take one. Is Pauls tarp a good tip for a European student, who wants to visit in his holydays different european countries? Please try again later. This probably means forest fires. So, what i want to say: We all together should think about the possibility of hybrid use of our equipment, and find out the best for both worlds, because most of us are dancing on both parties! For staying in touch on the trails, CB radios are popular. It can be hard to track down propane in some countries, so play it safe and bring your own fuel. Bad weather, unexpected overnights, ankle sprains and worse: Anything can happen in the backcountry. If you get something in your eye it can be nice to be able to see where the problem is so you can treat it better. Cost should not be an issue. Sometimes forced by government, sometimes being inexperienced, sometimes by preference. You can use many items for several applications, including emergencies. Depending on your style, your personal camping checklist might vary drastically from mine. These are important in case you need to assist someone who is injured. There was some debate among our experts about which levels to add nail clippers, toilet paper, and wet wipes. Prevent bug bites from happening in the first place thanks to insect repellent. Camping list with everything you need for your next adventure, with a printable PDF packing list broken down by category. -

User Manual & Recipe Book

VACUUM SEALING SYSTEM VACUUM SEALING SYSTEM 3FHJTUFSJOHZPVSBQQMJBODFJTRVJDLBOEFBTZBUXXXGPPETBWFSDPNSFHJTUFS*GZPV SFHJTUFSPOPVSXFCTJUF ZPVXJMMIBWFUIFPQQPSUVOJUZUPSFDFJWFTQFDJBMCBHBOEBDDFTTPSZ JOUSPEVDUPSZPGGFST3FGFSUPUIFSFHJTUSBUJPODBSEJOTJEFUIFCPY 'PSJNQPSUBOUTBGFUZJOGPSNBUJPOBOEIFMQGVMUJQT QMFBTFWJTJUVTBUXXXGPPETBWFSDPN UPHFUUJQTPOWBDVVNTFBMJOHBOEPSEFS'PPE4BWFSCSBOEBDDFTTPSJFT CBHTBOESPMMT PSDBMM 64 6TFS.BOVBM 3FDJQF#PPL ©2010 Sunbeam Products, Inc. doing business as Jarden Consumer Solutions. All rights reserved. Distributed by GPS6TFSJFTBQQMJBODFT Sunbeam Products, Inc. doing business as Jarden Consumer Solutions, Boca Raton, Florida 33431. .PEFMT7 Printed in China. P.N. 139582 XXXGPPETBWFSDPN *NQPSUBOU4BGFHVBSET5JQT 8FMDPNFUP'PPE4BWFS7BDVVN4FBMJOH4ZTUFN *NQPSUBOU4BGFHVBSET *NQPSUBOU5JQT $POHSBUVMBUJPOT© 'SFF(JGUXJUI3FHJTUSBUJPO 'PSZPVSPXOTBGFUZ BMXBZTGPMMPXUIFTFCBTJD 1. Vacuum packaging is NOT a substitute for the Register now and you’ll receive QSFDBVUJPOTXIFOVTJOHB'PPE4BWFSBQQMJBODF heat process of canning. Perishables still need You are about to enjoy the freshness 1. Read the User Manual carefully for operating to be refrigerated or frozen. benefits of FoodSaver®, The #1 Selling a free gift. It’s our “thanks” to you 8&-$0.& instructions. Read all instructions in this manual 2. For best results, use only with FoodSaver® Bags, for being a FoodSaver® customer. before use. Rolls, Containers and Accessories. Brand of Vacuum Packaging Systems. For ® 2. Do not use appliance on wet surfaces or outdoors. 3. During the vacuum packaging process, small years, the FoodSaver Vacuum Packaging Register online at 3. To protect against electric shock, do not immerse amounts of liquids, crumbs or food particles System has helped millions of households www.foodsaver.com/register. any part of appliance, power cord or plug in water can be inadvertently pulled into the Vacuum or other liquid. Unplug from outlet when not in use Channel. Empty the Drip Tray after each use. keep food fresh longer in the refrigerator, You’ll have access to special sale and before cleaning. -

Salvatore Ferragamo Group Annual Report As at 31 December 2020

Annual Report 2020 Salvatore Ferragamo Group Annual Report as at 31 December 2020 Salvatore Ferragamo S.p.A. Florence General information Registered office Salvatore Ferragamo S.p.A. Via Tornabuoni, 2 - 50123 Florence Legal information Authorized share capital 16,939,000 Euro - Subscribed and paid-up share capital 16,879,000 Euro Tax code and Florence Company Register no.: 02175200480 Registered with the Florence Chamber of Commerce under REA (Economic and Administrative Register) no. 464724 - Corporate website https://group.ferragamo.com/it/ Salvatore Ferragamo Group Board of Directors’ report Contents Letter from the Chairman 4 Board of Directors’ report on operations as at 31 December 2020 6 Corporate boards 10 Group structure 12 Group description 13 Main Stock Market indicators – Salvatore Ferragamo S.p.A. 14 1. The Group’s main income and financial results for the year 2020 16 2. Introduction 18 3. The Salvatore Ferragamo Group’s activities 18 4. The Group’s operating performance 26 5. Operating performance of the Parent company Salvatore Ferragamo S.p.A.. 48 6. Reconciliation between the Parent company’s net profit/(loss) for the period and shareholders’ equity and the consolidated values of the Group 57 7. Results of Group companies 58 8. Significant events occurred during the year 59 9. Information on corporate governance and ownership structure 70 10. Other information 75 11. Research and development 78 12. Transactions with related parties 78 13. Main risks and uncertainties 79 14. Significant events occurred after 31 December 2020 86 15. Macroeconomic situation and outlook 86 16. Separate Financial Statements as at 31 December 2020 of Salvatore Ferragamo S.p.A.