John Chrysostom's Use of Luke 16:19–31

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Luke 16:19-31)

“A Final Word from Hell” (Luke 16:19-31) If you’ve ever flown on an airplane you’ve probably noticed that in the seat pocket ahead of you is a little safety information card. It contains lots of pictures and useful information illustrating what you should do if, for example, the plane you’re entrusting your life with should have to ditch in the ocean. Not exactly the kind of information most people look forward to reading as they’re preparing for a long flight. The next time you’re on an airplane, look around and see how many people you can spot actually reading the safety cards. Nowadays, I suspect you’ll find more people talking or reading their newspaper instead. But suppose you had a reason to believe that there was a problem with the flight you were on. Suddenly, the information on that card would be of critical importance—what seemed so unimportant before takeoff could mean the difference between life and death. In the same way, the information in the pages of God’s Word is critically important. The Bible contains a message that means the difference between eternal life and death. Yet, for many of us, our commitment to the Bible is more verbal than actual. We affirm that the Bible is God’s Word, yet we do not read it or study it as if God was directly communicating to us. If left with a choice, many of us would prefer to read the newspaper or watch TV. Why is this? Certainly one reason for this is that there is not a sense of urgency in our lives. -

Sept. 29 – the Invisible Challenge Luke 16:19-31 the Story of the Rich

Sept. 29 – The Invisible Challenge Luke 16:19-31 The story of the rich man and Lazarus is another of those well-known parables of Jesus that we often hear with selective hearing. We listen to those parts that comfort us and ignore those parts that challenge. What I mean is that often we first of all define, in our minds, the word rich. We are never in that category. Warren Buffet or Bill Gates, they are rich. This parable is about them and the other 1% group in our nation and how they should act. We inwardly smile that they are getting a “talking too” and hope they listen and treat the poor better than now is the case. We rarely place ourselves in Lazarus’ shoes and ask, “Is this story of Jesus for us?” What I want to do today is to have this parable of Jesus confront us and our actions and our assumptions. Look at the attitude of the rich man towards Lazarus. It is clearly shown in this painting. Lazarus is seen just outside the door of the rich man’s kitchen. He’s literally right there, not a full step away. But you have to look for him. The painting is so full of the riches of this kitchen, that Lazarus, though right at the door, is hard to see at all. This parable is a reminder for us to think about all those we interact with on a daily basis. Too often some become invisible. We don’t really see them or their needs; they are just there, part of the fabric of life. -

The Parables of Jesus Is That We Know the Punchline to the Stories (I.E

Sponsored by ENROLL occ.edu/admissions ONLINE COURSES occ.edu/online GIVE occ.edu/donate SESSION 1 -One of the problems with studying the parables of Jesus is that we know the punchline to the stories (i.e. we know how they end). -In this lesson we tell three stories outside of the Gospels to help us prepare for the study of the parables of Jesus. Three stories: # 1: Story of the Jewish tailor—there is such a thing as an enigmatic ending! Story leaves you wanting more! # 2: Story of the needy family with student in the signature group, “Impact Brass and Singers.” Story of the bad guy being the good guy! # 3: Story of the broken car and helping female faculty member by biker. Story of wrong perceptions and leaving open-ended. -Enigma, bad guys doing well, and wrong perceptions and open-ended are all characteristics of Jesus’ parables. SESSION 2 Resources -Kenneth Bailey says that Jesus was a “metaphoric theologian.” Well, if that’s true we are probably going to need some help understanding him because metaphor, symbolism and analogies are not always easy to interpret. Resources (from most significant to lesser significant): 1) Klyne Snodgrass, Stories with Intent. 2) Kenneth Bailey, Through Peasant Eyes, Poet and Peasant, and Jesus through Middle Easter Eyes. 3) Gary Burge, Jesus the Storyteller. 4) Craig Blomberg, Interpreting the Parables. 5) Craig Blomberg, Preaching the Parables. 6) Roy Clements, A Sting in the Tale. 7) C.H. Dodd, The Parables of the Kingdom. 8) William Herzog, The Parables as Subversive Speech. -

Rich Man and Lazarus March 14, 2021

A Mission Congregation of the ELCA Trinity Evangelical Lutheran Church P. O. Box 64 - 8520 Oakes Rd - Pitsburg, Ohio 45358 Rich Man and Lazarus March 14, 2021 • Prelude “Remember; Jesus Messiah; At the Cross” Darrell Fryman • Office of the Acolyte and Ringing of the Bell • Welcome Pr Mel ∗ CONFESSION AND FORGIVENESS All may make the sign of the cross, the sign marked at baptism, as the presiding minister begins. P: We confess our sins before God and one another. Pause for silence and reflection. P: God of mercy, C: Jesus was faithful even in the face of death, yet we so often fail you in day to day living. Our commitment is shaky, our promises are unreliable, and our actions are questionable. We quit when discipleship becomes difficult and complain that we don’t get enough credit. Forgive us our neglect of your mission and our lukewarm devotion and wake us up to the urgency of your gospel. P: God is gracious and pardons all our shortcomings. May the giver of life forgive us our sins and restore us to the joy of discipleship and service, for the sake of Jesus our faithful Lord. C: Amen. ∗ Please stand if able March 14, 2021 • Please be seated Page 2 of 15 ∗ HYMN OF PRAISE “When Peace, Like A River” LBW 346 Verses 1 & 4 Only ∗ APOSTOLIC GREETING P: The grace of our Lord Jesus Christ, the love of God, and the communion of the Holy Spirit be with you all. C: And also with you. ∗ PRAYER OF THE DAY P: Let us pray… Merciful God, you care deeply for those who are in need. -

Sunday School Lesson (Mark 10:17-27) Stewardship for Kids Ministry-To-Children.Com/Heart-Of-Giving-Lesson

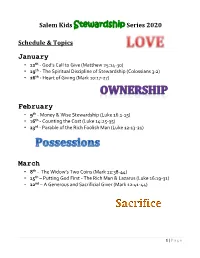

Salem Kids Stewardship Series 2020 Schedule & Topics January • 12th - God’s Call to Give (Matthew 25:14-30) • 19th - The Spiritual Discipline of Stewardship (Colossians 3:2) • 26th - Heart of Giving (Mark 10:17-27) February • 9th - Money & Wise Stewardship (Luke 16:1-15) • 16th - Counting the Cost (Luke 14:25-35) • 23rd - Parable of the Rich Foolish Man (Luke 12:13-21) March • 8th - The Widow’s Two Coins (Mark 12:38-44) • 15th – Putting God First - The Rich Man & Lazarus (Luke 16:19-31) • 22nd – A Generous and Sacrificial Giver (Mark 12:41-44) 1 | P a g e 2 | P a g e Lesson: God’s Call to Give (Matthew 25:14-30) Stewardship for Kids ministry-to-children.com/stewardship-lesson-1 Scripture: Matthew 25:14-30 Supplies: Pencils, paper, yellow circles of construction paper Lesson Opening: What is Stewardship? Ask: Has anyone ever heard the word “Steward” before? What do you think it means? (A steward is someone who takes care of another person’s property.) Ask: What does it mean to be responsible for something? Ask: What are some things that you are responsible for? Ask: Did you know that God has made each of us stewards? We are all stewards over the things that God entrusts to us. Say: We’ll hear a parable, or story, about 3 servants who were responsible for their master’s money. Pray that God would open their hearts to His Word today and that He would stir our hearts to be good stewards of His creation and that we would give back to Him with thankful hearts. -

NEW TESTAMENT READING PLAN (WITH OLD TESTAMENT REFERENCES) ------Week 5 Summary

NEW TESTAMENT READING PLAN (WITH OLD TESTAMENT REFERENCES) ------------------------------------------------------------ Week 5 summary: More teaching from Jesus this week. Jesus continually teaches about being His disciples. Maybe another way to say that is that He teaches about being members of the Kingdom of God. (A kingdom implies there is a king. In this Kingdom, the King is Jesus. What do you do for a King? Obey him!) Jesus is to the point in His teachings. Even though He teaches in parables, there is no doubt what His expectations are for His disciples. Day 1: Luke 10-11; John 10:22-42 Luke 11:28 says that we should hear God's word and put it into practice (or in other words, obey it). Starting in Luke 11:37, there are several verses where Jesus is confronting the beliefs of the Jewish leaders. The section heading in the Bibles I looked at described this section of scripture these ways: 1) Jesus condemns Pharisees and the Legal Experts; 2) Woes on the Pharisees and Experts in the Law; 3) Jesus Criticizes the Religious Leaders. Depending on the translation of the Bible you are using, you may find Jesus saying, “What sorrow awaits you...,” or “How terrible for you...,” or “Woe to you...” Whichever translation you choose to use, Jesus' language is pretty clear. The people He was talking to were severely missing the boat related to how to obey God's law. Day 2: Luke 12-13 Luke 12:10 talks about an unpardonable sin, attributing the works of the Holy Spirit to the devil, which denies the work of God. -

March 14Th Discussion Guide LENT SERIES: PARABLE of the RICH MAN and LAZARUS

March 14th Discussion Guide LENT SERIES: PARABLE OF THE RICH MAN AND LAZARUS This is a 5 week study called Stories to live by: A Lent series on the Parables of Jesus. Content for this discussion guide is based on the sermon, so participation in weekly worship will enhance the conversation on this topic. If you want to watch the sermon it can be viewed at Sermons Archive - Good Shepherd Church Naperville Prayer Open your group in prayer. Icebreaker (10 min) 1. Share a time someone generously helped you. 2. What charity is dear to your heart? Why do you support it? 1 Discussion (30 min) 1. Read Luke 16:19-31, Revelation 3:17, 1 John 3:17, and Luke 16:14-15. a. Why was the Rich Man in Hades? What mistakes did he make? b. What ladders does the world try to climb to earn favor with God and man? How do we look for help in things of this world rather than God or help ourselves rather than others? c. How do you relate to the Rich Man? 2. Re-read Luke 16:31 and John 11:38-44. a. What point was Jesus trying to make in verse 31? b. What stops the world from believing that Jesus raises people from the dead? What do you believe? c. Have you shared with those you love about the chasm between Hades and Heaven? How did they respond? 3. Read Psalm 118:7, Isaiah 41:10 and Hebrews 2:14-18. a. Keeping in mind the name Lazarus means “God has helped”, how was the Lazarus in this parable helped? b. -

1 Luke 16:19-31 – “Which One Are You: the Rich Man Or Lazarus?” By

Luke 16:19-31 – “Which One Are You: The Rich Man or Lazarus?” by Pastor Kevin Wattles preached at Grace Evangelical Lutheran Church Falls Church, Virginia 19 th Sunday after Pentecost, October 3, 2010 Right now in our home stories are a big thing. Our family has my wife, Jill, an almost ten-year-old Kortney, six- year-old Josh, sixteen-month-old Jason, and myself. With children the age of my family’s, you can understand why stories are a big thing in our family right now. Often stories are being read; and stories are being listened to. Jesus was quite a story-teller while he was on earth. Everything Jesus did while he was on earth he did expertly…perfectly…completely. When Jesus gained our salvation…he gained it fully, completely, perfectly— there’s nothing yet to be done in terms of our salvation. When Jesus healed someone; the person was healed. The leprosy didn’t come back in six months. When Jesus forgave someone her or his sins; they were forgiven. There was no need for penance; no need to do something to complete the forgiveness process. The same can be said for Jesus’ story-telling ability. Jesus was a master story-teller. He could really engage his listeners. Jesus was a master illustrator. He could powerfully apply his messages to his listeners’ lives. Last Sunday we had one of Jesus’ stories as our message lesson, “The Parable of the Shrewd Manager.” Today we have another story of Jesus before us. It’s the story that’s often called, “The Story of the Rich Man and Lazarus,” or sometimes he’s called “…Poor Lazarus.” Just like last Sunday when I asked you to listen to the story and think about what the story was about, I’m going to ask the same of you today. -

Luke 16:19-31) Retold in a Nigerian Context

Global Journal of Arts Humanities and Social Sciences Vol.2, No. 3, pp. 59-76, May 2014 Published by European Centre for Research Training and Development UK (www.ea-journals.org) THE STORY OF LAZARUS AND THE RICH MAN (LUKE 16:19-31) RETOLD IN A NIGERIAN CONTEXT John Arierhi Ottuh, Ph.D Vicar, Winners Baptist Church, Box 1214 Effurun, Delta State ABSTRACT: Poverty with its concomitant effects of alienation, marginalization and dependency posed serious challenge to the church and society in Nigeria. Both the Old and New Testaments condemned the dehumanization and neglect of the poor in the church community. Using the methodology of the popular reading paradigm to read Luke 16:19-31, the paper aimed at discouraging the dehumanization of the poor in the church and in the society. The study showed that both in the immediate and contemporary milieus of interpretation, the poor were ill- treated by some few rich persons in the society. Moreover, giving the poor a more human face can reshapen the economic and psychological disposition of the poor when they come around the rich. Some theological lessons derived from the study of Luke 16:19-31 showed that un- generosity towards the poor is a sin, status in God’s view is immaterial when dealing with others, dehumanization of poor people in the society is inhuman, a rich Christian must care for the less-privileged in the Church and society, a juxtaposition of the present and the afterlife gives the true picture of real life. This study was concluded on the presupposition that poverty alleviation in the Nigeria is possible if the church and the society (government) can do drastic poverty alleviation programme that can adequately address the economic situation of the poor beyond just feeding them. -

The Rich Man and Lazarus

P.O. Box 1058 • Roseville, CA 95678-8058 ISBN 1-58019-061-8 Library of Sermons 1. Armageddon 2. Can a Saved Man Choose to Be Lost? 3. Does God’s Grace Blot Out the Law? 4. Hidden Eyes and Closed Ears 5. How Evolution Flunked the Science Test 6. Is It Easier to Be Saved or to Be Lost? 7. Man’s Flicker or God’s Flame 8. Satan in Chains 9. Satan’s Confusing Counterfeits 10. Spirits From Other Worlds 11. Thieves in the Church Copyright © 2004 by 12. Why God Said Remember Lu Ann Crews 13. Why the Old Covenant Failed 14. The High Cost of the Cross 15. Hell-Fire All rights reserved. 16. Is It Possible to Live Without Sinning? Printed in the USA. 17. Blood Behind the Veil 18. Spirits of the Dead 19. The Brook Dried Up Published by: 20. Death in the Kitchen Amazing Facts, Inc. 21. The Search for the True Church P.O. Box 1058 22. Is It a Sin to Be Tempted? 23. Is Sunday Really Sacred? Roseville, CA 95678-8058 24. Heaven ... Is It for Real? 800-538-7275 25. Rendezvous in Space 26. Christ’s Human Nature Layout by Greg Solie - Altamont Graphics 27. Point of No Return Cover design by Haley Trimmer 28. The Rich Man and Lazarus For more great resources, visit us at www.amazingfacts.org The Rich Man and Lazarus 12/18/03 10:01 AM Page 1 The Rich Man and Lazarus 12/18/03 10:01 AM Page 2 THE RICH MAN AND LAZARUS uch argument has taken place over whether the words of Jesus M in Luke 16:19-31 were intended to be understood literally or as a parable. -

Representations of the Afterlife in Luke-Acts Somov, A

VU Research Portal Representations of the Afterlife in Luke-Acts Somov, A. 2014 document version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link to publication in VU Research Portal citation for published version (APA) Somov, A. (2014). Representations of the Afterlife in Luke-Acts. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. E-mail address: [email protected] Download date: 25. Sep. 2021 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This work could not have been completed without the help and support of several people whom I would like to thank here. First of all, I am very grateful to my supervisor Prof. Dr. Bert Jan Lietaert Peerbolte to whom I would like to express my deepest appreciation for his careful reading of my manuscript, generous and effective feedback, and advice as well as encouragement throughout the years of my research. Secondly, I would like to give my sincere thanks to my co-supervisors Dr. -

The Rich Man and Lazarus

The Rich Man and Lazarus By J. N. Andrews ARE the wicked dead now being punished? This is a question of awful solemnity, and should not be treated as a matter of speculation and idle curiosity. For the greater part of mankind live in neglect of the great duties of religion, if not in open contempt of its most solemn commands. Such has ever been the fact with our fallen race. This vast throng of sinful men for long ages have been pouring through the gates of death, and its dark portals hide them from our further view. What is the condition of this innumerable multitude of impenitent dead? Where are they? and what now is their real state? To this question two answers are returned: 1. They are now suffering the torments of the damned. This is the answer of the so-called orthodox creeds. 2. They are now sleeping in the dust of the earth, awaiting the resurrection to damnation. This answer is believed by many candid Bible students to be the harmonious teaching of the Scriptures on this subject. Which of these two answers is the true and proper one? 1. There is no statement in the Bible relating to the wicked dead in general, where they are in any way represented as in a state or place of torment. Nor is there any instance in the Bible where men are threatened that they shall, if wicked, enter an abode of misery at death. Even the warning of Jesus, in Matt. 10:28, which is thought to contain the strongest proof of the soul's immortality that can be found in all the Bible, says not one word concerning the suffering of the soul in hades, the place of the dead, but relates wholly to what shall be inflicted upon "both soul and body in gehenna" (the Greek word here rendered hell), the place of punishment for the resurrected wicked.