How to Recapture the Thrill for Basic Sciences in Higher Education By

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Current Affairs October 2019

LEGEND MAGAZINE (OCTOBER - 2019) Current Affairs and Quiz, English Vocabulary & Simplification Exclusively prepared for RACE students Issue: 23 | Page : 40 | Topic : Legend of OCTOBER | Price: Not for Sale OCTOBER CURRENT AFFAIRS the two cities from four hours to 45 minutes, once ➢ Prime Minister was speaking at a 'Swachh completed and will also decongest Delhi. Bharat Diwas' programme in Ahmedabad on ➢ As much as 8,346 crore is likely to be spent the 150th birth anniversary of Mahatma Gandhi. NATIONAL NEWS on the project, which was signed in March, 2016. ➢ Mr Modi said, the Centre plans to spend 3 lakh crore rupees on the ambitious "Jal Jivan PM addresses Arogya Manthan marking one Raksha Mantri Excellence Awards for Mission" aimed at water conservation. year of Ayushman Bharat; employees of Defence Accounts Department ➢ Prime Minister also released Launches a new mobile application for was given on its annual day. commemorative 150 rupees coins to mark the Ayushman Bharat ➢ Defence Accounts Department, one of the occasion ➢ Prime Minister Narendra Modi will preside over oldest Departments under Government of India, Nationwide “Paryatan Parv 2019” to the valedictory function of Arogya Manthan in is going to celebrate its annual day on October 1. promote tourism to be inaugurated in New New Delhi a two-day event organized by the ➢ Rajnath Singh will be Chief Guest at the Delhi National Health Authority to mark the completion celebrations, which will take place at Manekshaw ➢ The nationwide Paryatan Parv, 2019 to of one year of Ayushman Bharat, Pradhan Centre in Delhi Cantt. Shripad Naik will be the promote tourism to be inaugurated in New Delhi. -

Postcoloniality, Science Fiction and India Suparno Banerjee Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, Banerjee [email protected]

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2010 Other tomorrows: postcoloniality, science fiction and India Suparno Banerjee Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Banerjee, Suparno, "Other tomorrows: postcoloniality, science fiction and India" (2010). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 3181. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/3181 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. OTHER TOMORROWS: POSTCOLONIALITY, SCIENCE FICTION AND INDIA A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College In partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy In The Department of English By Suparno Banerjee B. A., Visva-Bharati University, Santiniketan, West Bengal, India, 2000 M. A., Visva-Bharati University, Santiniketan, West Bengal, India, 2002 August 2010 ©Copyright 2010 Suparno Banerjee All Rights Reserved ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My dissertation would not have been possible without the constant support of my professors, peers, friends and family. Both my supervisors, Dr. Pallavi Rastogi and Dr. Carl Freedman, guided the committee proficiently and helped me maintain a steady progress towards completion. Dr. Rastogi provided useful insights into the field of postcolonial studies, while Dr. Freedman shared his invaluable knowledge of science fiction. Without Dr. Robin Roberts I would not have become aware of the immensely powerful tradition of feminist science fiction. -

The Venus Transit: a Historical Retrospective

The Venus Transit: a Historical Retrospective Larry McHenry The Venus Transit: A Historical Retrospective 1) What is a ‘Venus Transit”? A: Kepler’s Prediction – 1627: B: 1st Transit Observation – Jeremiah Horrocks 1639 2) Why was it so Important? A: Edmund Halley’s call to action 1716 B: The Age of Reason (Enlightenment) and the start of the Industrial Revolution 3) The First World Wide effort – the Transit of 1761. A: Countries and Astronomers involved B: What happened on Transit Day C: The Results 4) The Second Try – the Transit of 1769. A: Countries and Astronomers involved B: What happened on Transit Day C: The Results 5) The 19th Century attempts – 1874 Transit A: Countries and Astronomers involved B: What happened on Transit Day C: The Results 6) The 19th Century’s Last Try – 1882 Transit - Photography will save the day. A: Countries and Astronomers involved B: What happened on Transit Day C: The Results 7) The Modern Era A: Now it’s just for fun: The AU has been calculated by other means). B: the 2004 and 2012 Transits: a Global Observation C: My personal experience – 2004 D: the 2004 and 2012 Transits: a Global Observation…Cont. E: My personal experience - 2012 F: New Science from the Transit 8) Conclusion – What Next – 2117. Credits The Venus Transit: A Historical Retrospective 1) What is a ‘Venus Transit”? Introduction: Last June, 2012, for only the 7th time in recorded history, a rare celestial event was witnessed by millions around the world. This was the transit of the planet Venus across the face of the Sun. -

NGO Directory

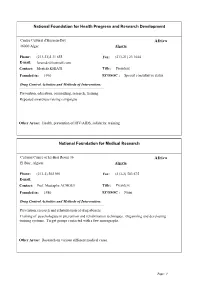

National Foundation for Health Progress and Research Development Centre Culturel d'Hussein-Day Africa 16000 Alger Algeria Phone: (213-21)2 31 655 Fax: (213-21) 23 1644 E-mail: [email protected] Contact: Mostefa KHIATI Title: President Founded in: 1990 ECOSOC : Special consultative status Drug Control Activities and Methods of Intervention: Prevention, education, counselling, research, training Repeated awareness raising campaigns Other Areas: Health, prevention of HIV/AIDS, solidarity, training National Foundation for Medical Research Cultural Centre of El-Biar Room 36 Africa El Biar, Algiers Algeria Phone: (213-2) 502 991 Fax: (213-2) 503 675 E-mail: Contact: Prof. Mustapha ACHOUI Title: President Founded in: 1980 ECOSOC : None Drug Control Activities and Methods of Intervention: Prevention, research and rehabilitation of drug abusers. Training of psychologists in prevention and rehabilitation techniques. Organizing and developing training systems. Target groups contacted with a few monographs. Other Areas: Research on various different medical cases. Page: 1 Movimento Nacional Vida Livre M.N.V.L. Av. Comandante Valodia No. 283, 2. And.P.24. Africa C.P. 3969 Angola, Rep. Of Luanda Phone: (244-2) 443 887 Fax: E-mail: Contact: Dr. Celestino Samuel Miezi Title: National Director, Professor Founded in: 1989 ECOSOC : Drug Control Activities and Methods of Intervention: Prevention, education, treatment, counselling, rehabilitation, training, and criminology To combat drugs and its consequences through specialized psychotherapy and detoxification Other Areas: Health, psychotherapy, ergo therapy Maison Blanche (CERMA) 03 BP 1718 Africa Cotonou Benin Phone: (229) 300850/302816 Fax: (229) 30 04 26 E-mail: Contact: Prof. Rene Gilbert AHYI Title: President Founded in: 1988 ECOSOC : None Drug Control Activities and Methods of Intervention: Prevention, treatment, training and education. -

THE RECORD NEWS ======The Journal of the ‘Society of Indian Record Collectors’ ------ISSN 0971-7942 Volume: Annual - TRN 2011 ------S.I.R.C

THE RECORD NEWS ============================================================= The journal of the ‘Society of Indian Record Collectors’ ------------------------------------------------------------------------ ISSN 0971-7942 Volume: Annual - TRN 2011 ------------------------------------------------------------------------ S.I.R.C. Units: Mumbai, Pune, Solapur, Nanded and Amravati ============================================================= Feature Articles Music of Mughal-e-Azam. Bai, Begum, Dasi, Devi and Jan’s on gramophone records, Spiritual message of Gandhiji, Lyricist Gandhiji, Parlophon records in Sri Lanka, The First playback singer in Malayalam Films 1 ‘The Record News’ Annual magazine of ‘Society of Indian Record Collectors’ [SIRC] {Established: 1990} -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- President Narayan Mulani Hon. Secretary Suresh Chandvankar Hon. Treasurer Krishnaraj Merchant ==================================================== Patron Member: Mr. Michael S. Kinnear, Australia -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Honorary Members V. A. K. Ranga Rao, Chennai Harmandir Singh Hamraz, Kanpur -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Membership Fee: [Inclusive of the journal subscription] Annual Membership Rs. 1,000 Overseas US $ 100 Life Membership Rs. 10,000 Overseas US $ 1,000 Annual term: July to June Members joining anytime during the year [July-June] pay the full -

Abstracts-Book-Final

Sci-Fi Group By Indian Association for Science Fiction Studies (IASFS) 1 INDEX Sr. Page Name Title No. no. 1. Editorial Board - 6 2. From chief editor’s desk - 7 DLKIA: A Deep Neural Network Based Gerard Deepak, Pushpa C N, Knowledge Integration Approach for 3. Ayush Kumar, Thriveni J, 8 Knowledge Base Generation for Science Venugopal K R Fiction as a Domain Androids, Surveillance and Evil: An 4. Dr Kasturi Sinha Ray 9 Overview of Jonathan Nolan’s Westworld Racial Discrimination and Scientific Priyadharshini Krishnan & 5. Amelioration in Isaac Asimov’s 10 Akshaya Subramaniam ‘The Weapon too dreadful to use’ A Post humanist Reading of Homo Deus: A 6. Shikha Khandpur 11 Brief History of Tomorrow S. Priya Dharshini, Dr C. G. Frankenfood: A Cornucopia in Paolo 7. 12 Sangeetha Bacigalupi’s The Windup Girl Abnormal Human Beings in Hindu 8. Dr Shantala K R 13 Mythology and Possible Medical Explanation Bangalore’s Urban Ecology Crises: Science 9. Dr Sindhu Janardan 14 Fiction to the Rescue? Dystopian Awakening: Ecocritical 10. Dr Swasti Sharma Rumination on Climate Change in Narlikar’s 15 “Ice Age Cometh” Science Fiction, Women and Nature: 11. Mr. Kailash ankushrao atkare 16 Ecological Perspective Cyrano de Bergerac: Father of Science- 12. Dr Jyothi Venktaesh 17 Fiction Literature in France? A Reflection Kavin Molhy P. S, Dr C. G. Delineation of Optimistic Women in The 13. 18 Sangeetha Calculating Stars Breaking the Myth: Women as Superheroines 14. Nabanita Deka 19 and Supervillains in a Dystopian World Female Characters in Science Fiction: 15. Dr Navle Balaji Anandrao Archetypal Messengers of Social Equity and 20 Equality Exploring the Gamut of African American 16. -

Neuf Au Rcpl Et Six Au

MAZAVAROO | N°28 | SAMEDI 8 FÉVRIER 2020 mazavaroo.mu RS 5.00 PAGES 4-5 Raj Pentiah : "Je regrette d'avoir cru dans le volume de mensonges de navin ramgoolam" SMP.MU 14 N°28 - SAMEDI 08 FEVRIER 2020 PAGES 6-7 Pages 18-19 Discours-Programme Neuf au RCpl et six au RCc MarieLes "YoungClaire Phokeerdoss Shots" Les Royalistes accaparent 1/3 de la RENCONTREcuvée de 2019 du MSM volent Marie Claire Phokeerdoss:la vedette « La SMP vient en aide aux démunis de Beau-Vallon » arie Claire Phokeerdoss est âgée de 73 ans. Elle a sous sa responsabilité deux petits-enfants et dépend uniquement de sa pension de vieillesse pour les nourrir. Marie Claire raconte qu’elle pu mo okip 2 zenfants, lavi trop Ms’occupe des enfants de sa fille chere, » affirme-t-elle. depuis qu’ils sont nés. « Zot ti Afin d’aider Marie Claire à encore tibaba ler zot inn vinn ress joindre les deux bouts, la SMP a avek moi. Ena fois zot mama vinn offert des fournitures scolaires à guet zot, » dit-elle avec tristesse. ses petits-enfants. « Ban zenfan la La septuagénaire ne baisse jamais inn gagne ban materiaux scolaires. PAGE 3 les bras. Avec le soutien des autres Zot inn gagne sak, soulier lekol, membres de sa famille, Marie cahier ek ban lezot zafer lekol, Claire essaie tant bien que mal » dit-elle avec satisfaction. « Sa editorial de subvenir aux besoins de ses fer moi enn gran plaisir ki ban deux petits-enfants, âgés de 5 association cuma SMP pe vinn et 11 ans. -

Catholicisme Et Hindouisme Populaire À L'île De La Reunion

Catholicisme et hindouisme populaire à l’île de La Reunion : contacts, échanges (milieu du XIXe-début du XXe siècle) Céline Ramsamy-Giancone To cite this version: Céline Ramsamy-Giancone. Catholicisme et hindouisme populaire à l’île de La Reunion : contacts, échanges (milieu du XIXe-début du XXe siècle). Histoire. Université de la Réunion, 2018. Français. NNT : 2018LARE0048. tel-02477436 HAL Id: tel-02477436 https://tel.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-02477436 Submitted on 13 Feb 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. UNIVERSITE DE LA REUNION FACULTE DES LETTRES ET DES SCIENCES HUMAINES Ecole Doctorale Lettres et Sciences Humaines Laboratoire OIES Thèse d’Histoire contemporaine Présentée par Céline Ramsamy-Giancone Catholicisme et hindouisme populaire à l’île de La Réunion : contacts, échanges (Milieu du XIXe - début du XXème siècle) 16 octobre 2018 Sous la direction de Prosper Eve Composition du Jury M. Ralph Schor Professeur, Université de Nice Rapporteur M. Jean-Marius Solo- MCF HDR, Université de Madagascar Rapporteur Raharinjanahary Mme -

Jayant Vishnu Narlikar Jayant Narlikar Was Born on July 19, 1938 In

Jayant Vishnu Narlikar Jayant Narlikar was born on July 19, 1938 in Kolhapur, Maharashtra and received his early education in the campus of Banaras Hindu University (BHU), where his father Vishnu Vasudeva Narlikar was Professor and Head of the Mathematics Department. His mother Sumati Narlikar was a Sanskrit scholar. After a brilliant career in school and college, Narlikar got his B.Sc. degree at BHU in 1957. He went to Cambridge for higher studies, becoming a Wrangler and Tyson Medallist in the Mathematical Tripos. He got his Cambridge degrees in mathematics: B.A.(1960), Ph.D. (1963), M.A. (1964) and Sc.D. (1976), but specialized in astronomy and astrophysics. He distinguished himself at Cambridge with the Smith’s Prize in 1962 and the Adams Prize in 1967. He later stayed on at Cambridge till 1972, as Fellow of King’s College (1963-72) and Founder Staff Member of the Institute of Theoretical Astronomy (1966-72). During this period he laid the foundations of his research work in cosmology and astrophysics in collaboration with his mentor Fred Hoyle. Narlikar returned to India to join the Tata Institute of Fundamental Research (1972-1989) where under his charge the Theoretical Astrophysics Group expanded and acquired international standing. In 1988 the University Grants Commission invited him to set up the proposed Inter-University Centre for Astronomy and Astrophysics (IUCAA) as its Founder Director. He held the Directorship of IUCAA until his retirement in 2003. Under his direction IUCAA has acquired a world-wide reputation as a centre for excellence in teaching and research in astronomy and astrophysics. -

Music Inspired by Astronomy, Organized by Topic an Annotated Listing by Andrew Fraknoi

Music Inspired by Astronomy, Organized by Topic An Annotated Listing by Andrew Fraknoi © copyright 2019 by Andrew Fraknoi. All rights reserved. Used with permission. Borresen: At Uranienborg Cage: Atlas Eclipticalis Glass: Orion Connections between astronomy and music have been proposed since the time of the ancient Greeks. This annotated listing of both classical and popular music inspired by astronomy restricts itself to music that has connections to real science -- not just an astronomical term or two in the title or lyrics. For example, we do not list Gustav Holst’s popular symphonic suite The Planets, because it draws its inspiration from the astrological, and not astronomical, characteristics of the worlds in the solar system. Similarly, songs like Soundgarden’s “Black Hole Sun” or the Beatles’ “Across the Universe” just don’t contain enough serious astronomy to make it into our guide. When possible, we give links to a CD and a YouTube recording or explanation for each piece. The music is arranged in categories by astronomical topic, from asteroids to Venus. Additions to this list are most welcome (as long as they follow the above guidelines); please send them to the author at: fraknoi {at} fhda {dot} edu Table of Contents Asteroids Meteors and Meteorites Astronomers Moon Astronomy in General Nebulae Black Holes Physics Related to Astronomy Calendar, Time, Seasons Planets (in General) Comets Pluto Constellations Saturn Cosmology SETI (Search for Intelligent Life Out There) Earth Sky Phenomena Eclipses Space Travel Einstein Star Clusters Exoplanets Stars and Stellar Evolution Galaxies and Quasars Sun History of Astronomy Telescopes and Observatories Jupiter Venus Mars 1 Asteroids Coates, Gloria Among the Asteroids on At Midnight (on Tzadik). -

UM-DAE CEBS Colloquia During Academic Year 2007-2008

UM-DAE CEBS Colloquia during Academic Year 2007-2008 21st May 2008 Prof. Sunil Mukhi Creativity in Science 7th May 2008 Prof. R. K. Manchanda Wonderful World of Dead Stars 30th April 2008 Prof. G. Krishnamoorthy Molecular Motion is Essential for Life 23rd April 2008 Dr. P. Hari Kumar (Knock)- INs and (Knock)- OUTs in Biology 16th April 2008 Dr. M.V. Pitke, Director; Nichegan Technologies Converting on idea into a product 09th April 2008 Dr. Amol Dighe The Elusive Neutrino 26th March 2008 Prof. P.P. Divakaran Calculus under the Cocoanut Trees 19th March 2008 Purvi Parikh Hindustani Music: History, Structure 12th March 2008 Dr. Jayant Narlikar The lighter side of Gravity 5th March 2008 Dr. Shiraz Minwalla The Gravity−Gauge Theory Correspondence 27th February 2008 Dr. V.K. Wadhawan Smart Structure 20th February 2008 Dr. A. K. Tyagi Nano Materials: Past, Present and Future 13th February 2008 Shri. Bhargav Ram Descent of the Heavens 6th February 2008 Prof. Govind Swarup, FRS Frontiers of Radio Astronomy: The Giant Meter Wave Radio Telescope 26th December 2007 Prof. Dipan Ghosh "Entanglement − a Quantum Magic?” 19th December 2007 Nisha Yadav “Indus Culture and its Script” 12th December 2007 Dr. Deepa Khushalani Nobel Chemistry −2007 5th December 2007 Dr. R. Nagrajan "Superconductivity in Quaternary Borocarbides – A classic case of how a scientific discovery is made” 28th November 2007 Dr. Pratap Raychaudhari Nobel Review Colloquium 21st November 2007 Dr. M. N. Vahia (Amrute Shaha) Vikram Sarabhai and Indian Space Programme 14th November 2007 Dr. M. N. Vahia “India in Space” 31st October 2007 Dr. -

Die Jagd Auf Die Venus

Andrea Wulf die jagd auf die venus 110095_Wulf_Jagd_Venus_Neu_oEN.indd0095_Wulf_Jagd_Venus_Neu_oEN.indd 1 007.03.127.03.12 16:3616:36 110095_Wulf_Jagd_Venus_Neu_oEN.indd0095_Wulf_Jagd_Venus_Neu_oEN.indd 2 007.03.127.03.12 16:3616:36 Andrea Wulf DIE JAGD AUF DIE VENUS und die Vermessung des Sonnensystems Aus dem Englischen übertragen von Hainer Kober C. Bertelsmann 110095_Wulf_Jagd_Venus_Neu_oEN.indd0095_Wulf_Jagd_Venus_Neu_oEN.indd 3 007.03.127.03.12 16:3616:36 Die Originalausgabe ist 2012 unter dem Titel »Chasing Venus« bei William Heinemann, London, erschienen. Verlagsgruppe Random House FSC-DEU-0100 Das für dieses Buch verwendete FSC®-zertifizierte Papier Munken Premium Cream liefert Arctic Paper Munkedals AB, Schweden. 1. Auflage © 2012 by Andrea Wulf © 2012 by C. Bertelsmann Verlag, München, in der Verlagsgruppe Random House GmbH Umschlaggestaltung: R·M·E Roland Eschlbeck und Rosemarie Kreuzer Bildredaktion: Dietlinde Orendi Satz: Uhl + Massopust, Aalen Druck und Bindung: GGP Media GmbH, Pößneck Printed in Germany ISBN 978-3-570-10095-0 www.cbertelsmann.de 110095_Wulf_Jagd_Venus_Neu_oEN.indd0095_Wulf_Jagd_Venus_Neu_oEN.indd 4 007.03.127.03.12 16:3616:36 Für Regan 110095_Wulf_Jagd_Venus_Neu_oEN.indd0095_Wulf_Jagd_Venus_Neu_oEN.indd 5 007.03.127.03.12 16:3616:36 110095_Wulf_Jagd_Venus_Neu_oEN.indd0095_Wulf_Jagd_Venus_Neu_oEN.indd 6 007.03.127.03.12 16:3616:36 Inhalt Vorbemerkung 11 Karten 12 Dramatis Personae 17 Prolog: Die Herausforderung 19 TEIL I Transit 1761 Kapitel 1 Der Aufruf 31 Kapitel 2 Die Franzosen sind die Ersten 51 Kapitel