Henry Ward VC

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ocm08458220-1834.Pdf (12.15Mb)

317.3M31 A 4^CHTVES ^K REGISTER, ^ AND 18S4. ALSO CITY OFFICEKS IN BOSTON, AND OTHKR USEFUL INFORMATION. BOSTON: JAMES LORING, 132 WASHINGTON STREET. — — ECLIPSES IN 1834. There will be five Eclipses this year, three of ike Svtf, and two of tht Moon, as follows, viz;— I. The first will be of the Sun, January, 9th day, 6h. 26m. eve. invisible. II. The second will likewise be of the Sun, June, 7th day, 5h. 12m. morning invisible. III. The third will be of the Moorr, June, 21st day, visible and total. Beginning Ih 52m. ^ Beginning of total darkness 2 55 / Middle 3 38 V, Appar. time End of total darkness (Moon sets). ..4 18 C morn. End of the Eclipse 5 21 j IV. The fourth will be a remarkable eclipse of the Sun, Sunday, the 30th day of November, visible, as follows, viz : Beginning Ih. 21m. J Greatest obscurity 2 40 fAppar. time End 3 51 ( even. Duration 2 30 * Digits eclipsed 10 deg. 21m. on the Sun's south limb. *** The Sun will be totally eclipsed in Mississippi, Alabama Georgia, South Carolina. At Charleston, the Sun will be totally eclipsed nearly a minute and a half. V. The fifth will be of the Moon, December 15th and I6th days, visible as follows viz : Beginning 15th d. lOli. Q2m. ) Appar. time Middle 16 5 > even. End 1 30 ) Appar. morn. Digits eclipsed 8 deg. 10m. (JU* The Compiler of the Register has endeavoured to be accurate in all the statements and names which it contains ; but when the difficulties in such a compilation are considered, and the constant changes which are occur- ring, by new elections, deaths, &c. -

Graves of Note 1950 Onwards

Graves of Note 1950 onwards Flight-Lieutenant Michael Withey, 9E25 F-L Withey was killed when his Gloster Meteor jet crashed at Kirkcaldy, Fife, on October 18, 1957. Eyewitnesses said the pilot stayed with his plane to prevent it crashing into a built-up area, which included a school. He was brought back to Malvern to be buried in Great Malvern Cemetery. A plaque was unveiled by Kirkcaldy Civic Society on Monday 8 September 2008, at the town’s Dunnikier Park, not far from the crash site. Mary Hamilton Cartland, L12 H2 Also known as Polly, Mary Scobell was born in Newent in 1877 or as the headstone states, in 1878, and married James Bertram Falkner Cartland in Newent in 1900. After the death of her husband, Mary opened a London dress shop to make ends meet and to raise her daughter, Dame Barbara Cartland, the renowned novelist, and two sons, both of whom were killed in battle in 1940. Mary died in Malvern in 1976. Graves of Note Pre-1950 The Victorian section of the cemetery contains approximately one thousand graves and is a record of some of the people who were involved in the development of the town into an influential hydrotherapy centre. Matthew Thomas Stevens, Plot 7 Born in London 1866, Matthew spent his childhood days at Powick in the family of Mr and Mrs Sayers as a ‘nurse child’ and then living in the household of widow Lydia Wodehouse at Ham Hall House, as one of four servants. He then started work as a reporter with local newspaper The Malvern News. -

Photographs of Individuals, Brown University Archives

Photographs of Individuals, Brown University Archives de Gortari, Carlos Salinas (h1989) deKlerk, John (Faculty) van der Kulk, Wouter (Faculty) von Dannenberg, Carl Richard (1930) Aarons, Leroy F. (1955) Abatuno, Michael Anthony (1946) Abbott, Alexander Hewes (1903) Abbott, Augustus Levi (1880) Abbott, Carl Hewes (1888) Abbott, Charles Harlan (1913) Abbott, Daniel (Faculty) Abbott, Douglas W. (1961) Abbott, Elizabeth (1964) Abbott, Granville Sharp (1860) Abbott, Harlan Page (1885) Abbott, Isabel Ross (1922) Abbott, James Percival (1874) Abbott, Jean (1950) Abbott, Michael D. (1969) Abbott, Samuel Warren Abdel-Malek, Kamal (Faculty) Abedon, Byron Henry (1936) Abelman, Alan Norman (1949) Abelon, A. Dean (1963) Abish, Walter Ablow, Keith Abraams, Edith (1934) Abraham, Amy (1942) Abraham, George (1940) Abrahams, Edward (Staff) Abrams, John (Staff) Acevedo, Maria (1989) Acosta, Thomas (1971) Adams, Carl Elmer (a1949) Adams, Carroll E. (1944) Adams, Charles Francis (1881) Adams, Charles Robert (1880) Adams, Clarence Raymond (1918) Adams, Edie (V) Adams, Edward August (1912) Adams, Edward Stone (1879) Adams, Elizabeth S. C. (Staff) Adams, Frederick F. (1936) Adams, Frederick N. (1960) Adams, George Henry (1921) Adams, Henry Sylvanus (1860) Adams, Herbert Matthews (1895) Adams, James Pickwell (Faculty) Adams, Jasper (1815) Adams, Leonard F. (1960) Adams, Levi C. (Faculty) Adams, Louis Charles (1937) Adams, Samuel (1897) Adams, Susan (1980) Updated 5/6/2015 Adams, Thomas Randolph (Faculty) Addison, Eleanor (1938) Adee, Elise Alvey (1940) Adenstedt, Gudrun L. (1959) Adkins, Elijah S. (1944) Adler, Susan (1958) Adler, Walter (1918) Aebischer, Patrick (Faculty) Affleck, George Frederick (1941) Affleck, James Gelston (1914) Affleck, Myron Hopkins Stron (1907) Ahearn, Edward J. (Faculty) Ahern, Edward Charles (1931) Ahlberg, Harold Ahlbum, Sumner Plant (1936) Aiken, George D. -

The Following Document Is Provided By

MAINE STATE LEGISLATURE The following document is provided by the LAW AND LEGISLATIVE DIGITAL LIBRARY at the Maine State Law and Legislative Reference Library http://legislature.maine.gov/lawlib Reproduced from scanned originals with text recognition applied (searchable text may contain some errors and/or omissions) DOCUMENTS l''RINTED DY ORDER OF THE LEGISLATURE OF THE ST A TE OF lVIAINE, DURL"\G ITS SESSION A. D. 1850. flunu~ta: WILLIAM T. JOHNSON, PRINTER TO THE STATE. I 850. AN ABSTRACT OF THB RETURNS OF CORPORATIONS, MADE TO THE OFFICE OF THE SECRETARY OF STATE, IN JANUARY, 1850, FOR THE YEAR Prepared and published agreeably to a Resolve of the Legislature, approved March, 24, 1843; By EZRA 13. FRENCH, Secretary of State. WM, T, JOHNSON, ........... PRINTER TO THE STATE. 185 0. STATE OF MAINE. Resolve authorizing the pr1:nting of the Returns of Clerks of Corpo· ·rations. RESOLVED, That the Secretary of State is hereby directed to cause the printing of four hundred copies of the returns of the several corpo rations ( excepting banks) of this State, comprising the name, residence, and amount of stock owned by each stockholder, and furnish each city, town and plantation, with a copy of the same. [Approved March 24, 1843.) LIST OF STOCKHOLDERS. THE following comprise a list of all the returns of clerks of corpora tions, that have been received at the office of the Secretary of State, for the year 1850. The abstracts of the returns of such corporations as are marked (*) did not specify the value of shares or the amount of their capital stock, nor is such information found in their acts of incorporation. -

The Social Composition of the Territorial Air Force 1930

The Territorial Air Force 1925-1957 – Officer Recruitment and Class Appendix 2 FRANCES LOUISE WILKINSON A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the University of Wolverhampton for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy January 2017 This work or any part thereof has not previously been presented in any form to the University or to any other body whether for the purposes of assessment, publication or for any other purpose (unless otherwise indicated). Save for any express acknowledgments, references and/or bibliographies cited in the work, I confirm that the intellectual content of the work is the result of my own efforts and of no other person. The right of Frances Louise Wilkinson to be identified as author of this work is asserted in accordance with ss.77 and 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. At this date copyright is owned by the author. Signature……………………………………….. Date…………………………………………….. Appendix Contents Pages Appendix 1 Officers of the reformed RAuxAF 4-54 Appendix 2 Officers commissioned into the RAuxAF With no squadron number given 55-61 Appendix 3 United Kingdom Officers of the Royal Air Force Volunteer Reserve 62-179 3 Officers of the Re-formed Royal Auxiliary Air Force 1946-1957 The following appendix lists the officers of the Royal Auxiliary Air Force by squadron. The date of commission has been obtained by using www.gazette-online.co.uk and searching the archive for each squadron. Date of commission data is found in the Supplements to the London Gazette for the date given. Where material has been found from other press records, interviews, books or the internet, this has been indicated in entries with a larger typeface. -

The Royal Regiment of Scotland a Soldier's Handbook

The Royal Regiment of Scotland SCOTS A Soldier’s Handbook Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth the Second Colonel in Chief The Royal Regiment of Scotland Contents Section Page Introduction 3 The Structure of the Regiment 3 Uniform 7 Regimental Miscellany 12 History Part One 19 History Part Two 25 History Part Three 30 Victoria Crosses 36 Values and Standards of the British Army 40 List of Illustrations Colour Sergeant on Parade Cover The Colonel in Chief 1 Regimental Headquarters 3 On Patrol in Afghanistan 4 Training in Belize, Central America 5 Afghanistan 2006 6 Capbadge and Tactical Recognition Flash 7 Hackles 8 Number 1 Dress Ceremonial 9 Jocks in Action 11 The Military Band 12 Remembrance Day Baghdad 13 Piper in Iraq 14 Air Assault 15 The Golden Lions Scottish Infantry Parachute Display Team 16 The Regimental Kirk 17 Regimental Family Tree 18 A Soldier of Hepburn’s Regiment 1633 19 A Grenadier of Hepburn’s Regiment at Tangier 1680 20 Crawford’s Highlanders at Fontenoy 21 Battle of Ticonderoga 21 Battle of Minden 22 The Duke of Wellington 23 The Duchess of Gordon 24 Piper Kenneth Mackay 25 The Troopship Birkenhead 26 The Thin Red Line 27 William McBean VC 28 Winston Churchill 30 Robert McBeath VC 31 Dennis Donnini VC 32 William Speakman VC 33 Armoured Infantry in Iraq 35 Regimental Capbadge Back Cover 2 The Royal Regiment of Scotland INTRODUCTION The Royal Regiment of Scotland is Scotland’s Infantry Regiment. Structured, equipped and manned for the 21st Century, we are fiercely proud of our heritage. Scotland has a tradition of producing courageous, resilient, tenacious and tough, infantry soldiers of world renown. -

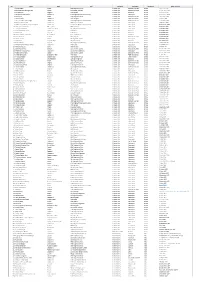

Nr1 Name Rank Unit Campaign Campaign. Campaign.. Date Of

Nr1 Name Rank Unit Campaign Campaign. Campaign.. Date of action 1 Thomas Beach Private 55th Regiment of Foot Crimean War Battle of Inkerman Crimea 5 November 1854 2 Edward William Derrington Bell Captain Royal Welch Fusiliers Crimean War Battle of the Alma Crimea 20 September 1854 3 John Berryman Sergeant 17th Lancers Crimean War Balaclava Crimea 25 October 1854 4 Claude Thomas Bourchier Lieutenant Rifle Brigade (Prince Consort's Own) Crimean War Sebastopol Crimea 20 November 1854 5 John Byrne Private 68th Regiment of Foot Crimean War Battle of Inkerman Crimea 5 November 1854 6 John Bythesea Lieutenant HMS Arrogant Crimean War Ã…land Islands Finland 9 August 1854 7 The Hon. Clifford Henry Hugh Lieutenant Rifle Brigade (Prince Consort's Own) Crimean War Battle of Inkerman Crimea 5 November 1854 8 John Augustus Conolly Lieutenant 49th Regiment of Foot Crimean War Sebastopol Crimea 26 October 1854 9 William James Montgomery Cuninghame Lieutenant Rifle Brigade (Prince Consort's Own) Crimean War Sebastopol Crimea 20 November 1854 10 Edward St. John Daniel Midshipman HMS Diamond Crimean War Sebastopol Crimea 18 October 1854 11 Collingwood Dickson Lieutenant-Colonel Royal Regiment of Artillery Crimean War Sebastopol Crimea 17 October 1854 12 Alexander Roberts Dunn Lieutenant 11th Hussars Crimean War Balaclava Crimea 25 October 1854 13 John Farrell Sergeant 17th Lancers Crimean War Balaclava Crimea 25 October 1854 14 Gerald Littlehales Goodlake Brevet Major Coldstream Guards Crimean War Inkerman Crimea 28 October 1854 15 James Gorman Seaman -

Historic Manuscripts Collection Legal Matters Documents

Grems-Doolittle Library Schenectady County Historical Society 32 Washington Ave., Schenectady, NY 12305 (518) 374-0263 [email protected] Historic Manuscripts Collection Legal Matters Documents No. Date Description LM 1 27 Mar 1827 In Chancery. At Albany. Thomas Foulger vs. William Hannah & James Comb; James Combs, Jr., Garret G. Clute; Abraham Van Patten; Isaac Wemple; Richard Miller. Names: Platt Potter, Alonzo C. Paige, Julius Rhoades, Correy’s Brook, Akus Peak, J.G. Porter. LM 2 1843 In Chancery. S Jones Mumford vs. Executors of estate of Henry Aster LM 3 28 Jan 1830 In Chancery. Daniel D Campbell vs. Joseph C Yates. Names: James Van Slyke Ryley, Jacob TB Van Vechten. LM 4 13 July 1847 The plea and answer of Joseph C Yates to the bill of complaint of Daniel D Campbell. Names: Original filed Angelica Campbell; Stephen Van Rensselaer; John Sanders; Daniel McCormick; Andrew Brown; 21 June 1830 Richard Hale; Litle Mickey; John H. Moyston; Walter Cochran; James Cochran; Richard Duncan; James Van Slyck Ryley; Myndert Vedder; Jacob Schermerhorn; William Teller; H.E. Yates; Harmanus Peek; Giles F. Yates; Edward Yates, PP.23-26 is interesting to read. LM 5 27 Jan 1832 In Chancery, before Chancellor Daniel David Campbell vs. Joseph C Yates for debts & costs. Names: Jacob Van Vechten LM 6 4 Feb 18 Letter from Joseph C Yates to Abraham Van Vechten re: case in Chancery: attached is affidavit of Joseph C Yates re: case with Daniel David Campbell. Names: Abraham Van Vechten LM 7 10 May 1830 In Supreme Court: Augustus Gombault vs. Herman I.