Repor T Resumes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Emission Station List by County for the Web

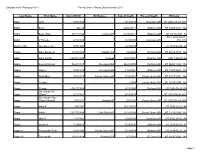

Emission Station List By County for the Web Run Date: June 20, 2018 Run Time: 7:24:12 AM Type of test performed OIS County Station Status Station Name Station Address Phone Number Number OBD Tailpipe Visual Dynamometer ADAMS Active 194 Imports Inc B067 680 HANOVER PIKE , LITTLESTOWN PA 17340 717-359-7752 X ADAMS Active Bankerts Auto Service L311 3001 HANOVER PIKE , HANOVER PA 17331 717-632-8464 X ADAMS Active Bankert'S Garage DB27 168 FERN DRIVE , NEW OXFORD PA 17350 717-624-0420 X ADAMS Active Bell'S Auto Repair Llc DN71 2825 CARLISLE PIKE , NEW OXFORD PA 17350 717-624-4752 X ADAMS Active Biglerville Tire & Auto 5260 301 E YORK ST , BIGLERVILLE PA 17307 -- ADAMS Active Chohany Auto Repr. Sales & Svc EJ73 2782 CARLISLE PIKE , NEW OXFORD PA 17350 717-479-5589 X 1489 CRANBERRY RD. , YORK SPRINGS PA ADAMS Active Clines Auto Worx Llc EQ02 717-321-4929 X 17372 611 MAIN STREET REAR , MCSHERRYSTOWN ADAMS Active Dodd'S Garage K149 717-637-1072 X PA 17344 ADAMS Active Gene Latta Ford Inc A809 1565 CARLISLE PIKE , HANOVER PA 17331 717-633-1999 X ADAMS Active Greg'S Auto And Truck Repair X994 1935 E BERLIN ROAD , NEW OXFORD PA 17350 717-624-2926 X ADAMS Active Hanover Nissan EG08 75 W EISENHOWER DR , HANOVER PA 17331 717-637-1121 X ADAMS Active Hanover Toyota X536 RT 94-1830 CARLISLE PK , HANOVER PA 17331 717-633-1818 X ADAMS Active Lawrence Motors Inc N318 1726 CARLISLE PIKE , HANOVER PA 17331 717-637-6664 X 630 HOOVER SCHOOL RD , EAST BERLIN PA ADAMS Active Leas Garage 6722 717-259-0311 X 17316-9571 586 W KING STREET , ABBOTTSTOWN PA ADAMS Active -

Obituary Index February 2021 Forest Grove Library Obituary Index S-U

Obituary Index February 2021 Forest Grove Library Obituary Index S-U Last Name First Name Date of Birth Birthplace Date of Death Place of Death Obituary Saari Lynn 10/3/1923 9/12/2018 Gresham OR NT 2018-11-07, A11 Sabin Bettie Age 86 03/06/2011 Hillsboro OR NT 03/09/2011, 12a Sabin Bettie Ellen 07/11/1924 Carlton OR 03/06/2011 Hillsboro OR NT 03/16/2011, 8a WCT 2020-05-07, Sabin C Eugene 6/15/1920 4/29/2020 Cornelius OR A10, A12 Saccheri Sr Joseph V "Joe" 8/30/1958 2/23/2019 NT 2019-03-06, A9 Sacks Mary Elizabeth 11/29/1922 Haddam KS 4/6/2008 Portland OR NT 04/16/2008, 12a Sadd Mary Sarah C02/07/1830 Canada 12/23/1901 Thatcher OR FGT 1902-01-02 Sadler Kenneth Bruch 06/23/1917 Cleveland OH 05/28/1998 Portland OR NT 06/03/1998, 17a Sadler Nancy 1/14/1919 Cleveland OH 11/2/2001 Hillsboro OR NT 11/07/2001, 11a Sagar Doris Mae 3/20/1917 Forest Grove OR 1/14/2001 Forest Grove OR NT 01/17/2001, 15a Sagar George c1989 Forest Grove OR NT 12/29/1999, 12a Sagar George c06/27/1888 6/23/1980 Portland OR NT 1980-06-25, B8 Gwendolyn M Sagar “Gwen” 2/21/1921 4/18/2015 NT 2015-05-06, A11 Gwendolyn Mae Sagar “Gwen” Howell 02/21/21 Omaha NE 04/18/15 Forest Grove OR NT 2015-04-29, A10 Sagar Mary K 2/3/1941 12/13/2016 NT 2016-12-21, A8 Sagar Mattie C07/27/1899 Little Rock AR 12/26/1999 Forest Grove OR NT 12/29/1999, 12a Sagar Nick K 6/7/1967 7/29/2016 Cornelius OR NT 2016-08-03, A8 Sagar Wyatt M 7/29/2016 7/29/2016 Hillsboro OR NT 2016-08-10, A7 Sagar Jr Thomas M "Tom" 1/14/1942 Forest Grove OR 5/14/2014 Hillsboro OR NT 2014-05-21, A8 Sagar Sr Thomas M 10/19/1918 -

BRAVE BIRDS By: PDSA - the UK’S Leading Veterinary Charity

BRAVE BIRDS By: PDSA - the UK’s leading veterinary charity. Additional text and photos courtesy of Australian War Memorial and UK Flightglobal Archive. The most famous and the oldest of the charity’s awards is the PDSA Dickin Medal. It acknowledges outstanding acts of bravery displayed by animals serving with the Armed Forces or Civil Defence units in any theatre of war, worldwide. The Medal is recognised as the animals’ Victoria Cross and is the highest British honour for animal bravery in military conflicts. The medal was instituted in 1943 Maria Dickin. Maria Dickin CBE PDSA owes its foundation to the vision of one woman - Maria Elisabeth Dickin - and her determination to raise the status of animals, and the standard of their care, in society. During the First World War, Maria Dickin CBE worked to improve the dreadful state of animal health in the Whitechapel area of London. She wanted to open a clinic where East Enders living in poverty could receive free treatment for their sick and injured animals. Left: Despite the scepticism of the Establishment, Maria Dickin opened her free 'dispensary' in a Whitechapel basement on Saturday 17th November 1917. It was an immediate success and she was soon forced to find larger premises. Photo PDSA. Within six years this extraordinary woman had designed and equipped her first horse-drawn clinic and soon a fleet of mobile dispensaries was established. PDSA vehicles soon became a comforting and familiar sight throughout the country. With success came increased attention from her critics at the Royal College of Veterinary Surgeons and the Ministry of Agrigulture. -

Les Pigeons Voyageurs Pendant La Guerre De 39-45

Bonne après-midi ! Il est 17 h 34 Nous sommes le 16 septembre 2019 Twitter entrée Généralités : accueil Présentation de l'espèce Les maladies du pigeon LA GUERRE Histoire du pigeonnier Histoire du pigeon voyageur Prolifération des pigeons de ville Dégâts des pigeons de ville Moyens de contrôle de sa population : - moyens barbares - méthodes douces - l'azacholestérol - législation DE Le pigeonnier de ville moderne : - Son histoire en région parisienne - avantages et inconvénients - aspects financiers - aspects pratiques quelques photos de pigeonniers : - Boulogne-Billancourt - Aulnay-sous-Bois 1939 - 1945 - Bobigny - Chatillon - Clamart - Meudon - Montrouge - Paris LIENS INTERNES - Fontenay-sous-Bois - Puteaux introduction - Sénat Paris - en région parisienne Les pigeons américains - en France, à l'étranger Les pigeons anglais pétition(s) en ligne livre d'or - vos commentaires La médaille Dickin poster un commentaire au livre d'or Les pigeons voyageurs, agents de liaison des Forces armées en temps de guerre Source : Maison du Souvenir Pendant la bataille d’Afrique du Nord, devant Tobrouck, un chef de char lâche un pigeon signalant sa position. Malgré les moyens de communication des plus modernes dont disposaient les armées alliées au cours de la dernière guerre mondiale et au Vietnam, il est fréquemment arrivé qu'il s'avérait impossible d'assurer des liaisons avec les états-majors. C'est ainsi qu'il a fallu souvent faire appel, comme on l'avait fait pendant la Première Guerre mondiale, à de modestes pigeons pour transmettre des messages, urgents et importants. Des dizaines de milliers de pigeons voyageurs ont ainsi été mis à la disposition des Alliés par les colombophiles britanniques, pour servir sur tous les fronts (Europe occupée, Afrique et Moyen-Orient), lorsque les moyens classiques de communication étaient devenus inopérants. -

Pigeons Guerre 39-45

Bonne après-midi ! Il est 17 h 53 Nous sommes le 7 janvier 2018 Twitter entrée Généralités : accueil Présentation de l'espèce Les maladies du pigeon LA GUERRE Histoire du pigeonnier Histoire du pigeon voyageur Prolifération des pigeons de ville Dégâts des pigeons de ville Moyens de contrôle de sa population : - moyens barbares - méthodes douces - l'azacholestérol DE - législation Le pigeonnier de ville moderne : - Son histoire en région parisienne - avantages et inconvénients - aspects financiers - aspects pratiques quelques photos de pigeonniers : - Boulogne-Billancourt 1939 - 1945 - Aulnay-sous-Bois - Bobigny - Chatillon - Clamart - Meudon LIENS INTERNES - Montrouge - Paris introduction - Fontenay-sous-Bois Les pigeons américains - Puteaux - Sénat Paris Les pigeons anglais - en région parisienne - en France, à l'étranger La médaille Dickin pétition(s) en ligne livre d'or - vos commentaires poster un commentaire au livre d'or Les pigeons voyageurs, agents de liaison des Forces armées en temps de guerre Source : Maison du Souvenir Pendant la bataille d’Afrique du Nord, devant Tobrouck, un chef de char lâche un pigeon signalant sa position. Malgré les moyens de communication des plus modernes dont disposaient les armées alliées au cours de la dernière guerre mondiale et au Vietnam, il est fréquemment arrivé qu'il s'avérait impossible d'assurer des liaisons avec les états-majors. C'est ainsi qu'il a fallu souvent faire appel, comme on l'avait fait pendant la Première Guerre mondiale, à de modestes pigeons pour transmettre des messages, urgents et importants. Des dizaines de milliers de pigeons voyageurs ont ainsi été mis à la disposition des Alliés par les colombophiles britanniques, pour servir sur tous les fronts (Europe occupée, Afrique et Moyen-Orient), lorsque les moyens classiques de communication étaient devenus inopérants. -

Winkie Dm 1 Pdsa Dickin Medal Winkie Dm 1

WINKIE DM 1 PDSA DICKIN MEDAL WINKIE DM 1 “For delivering a message under exceptionally difficult conditions and so contributing to the rescue of an Air Crew while serving with the RAF in February, 1942.” Date of Award: 2 December 1943 WINKIE’S STORY Carrier pigeon, Winkie, received the first PDSA Dickin Medal from Maria Dickin on 2 December 1943 for the heroic role she played in saving the lives of a downed air crew. The four-man crew’s Beaufort Bomber ditched in the sea more than 100 miles from base after coming under enemy fire during a mission over Norway. Unable to radio the plane’s position, they released Winkie and despite horrendous weather and being covered in oil, she made it home to raise the alarm. Home for Winkie was more than 120 miles from the downed aircraft. Her owner, George Ross, discovered her and contacted RAF Leuchars in Fife to raise the alarm. “DESPITE HORRENDOUS WEATHER AND BEING COVERED IN OIL SHE MADE IT HOME ...” Although it had no accurate position for the downed crew, the RAF managed to calculate its position, using the time between the plane crashing and Winkie’s return, the wind direction and likely effect of the oil on her flight speed. They launched a rescue operation within 15 minutes of her return home. Following the successful rescue, the crew held a celebration dinner in honour of Winkie’s achievement and she reportedly ‘basked in her cage’ as she was toasted by the officers. Winkie received her PDSA Dickin Medal a year later. -

Prairie Falcon Northern Flint Hills Audubon Society Newsletter

Full moon listening stroll. We will listen to the night sounds at the Carnahan area of Tuttle Creek Lake on Nov. 24th. Hearing owls is our particular mission but we anticipate other night sounds to intrigue us as well. Silence is golden. Meet near the toilet building ( not glamorous but central and easy to find) at 5:00 p.m. If you do not know this location or would like to carpool, meet at Sojourner Truth Park parking lot at 4:30 p.m. and a lead car will take you to the Carnahan Area. Dress for the cold and bring a flashlight. Car poolers plan to return by 8:00 p.m. Rain or wind over 20 mph cancels stroll. Hope to see you there. Patricia Yeager A pleasant evening was spent with Scott Bean and his photographs of outdoor Kansas. There were about 25 in attendance. Travel tips to the Kansas destinations pictured were shared. The evening certainly- in spired me to get out a explore Kansas. Kathy Bond's mother recently passed and a memorial donation was given to NFHAS in her name. Thank you. prairie falcon Northern Flint Hills Audubon Society Newsletter Vol. 47, No. 3 ~ November 2018 Northern Flint Hills Audubon Society, Society, Audubon Hills Flint Northern KS 66505-1932 Box 1932, Manhattan, P.O. Inside Upcoming Events pg. 2 -Skylight Nov. 3 - BIRDSEED PICKUP - UFM parking lot 8-11 a.m. Pete Cohen Nov. 5 - Board Meeting, 6 p.m. Friends’ Room pg. 3 -The Ubiquitous Bird Manhattan Public Library Dru Clarke Nov. 13 - Saturday Birding 8 a.m. -

DAPPERE DUIVEN Tekst: PDSA - People's Dispensary for Sick Animals, Engeland

DAPPERE DUIVEN Tekst: PDSA - People's Dispensary for Sick Animals, Engeland. Aanvullende tekst en foto’s: met dank aan Australian War Memorial en UK Flightglobal Archive. De PDSA Dickin Medaille is de bekendste en oudste liefdadigheids- medaille ter erkenning voor daden van bijzondere moed getoond door dieren waar ook ter wereld, in dienst van militaire en civiele eenheden ten tijde van oorlog. De medaille wordt erkend als het 'Victoria Cross’ voor dieren en is de hoogste Britse onderscheiding voor dapperheid in militaire conflicten en is ingesteld in 1943 door Maria Dickin. Maria Dickin CBE De PDSA is opgericht dankzij een vrouw - Maria Elisabeth Dickin – en haar vastberadenheid om de status van de dieren en de kwaliteit van hun verzorging in de samenleving te verhogen. Tijdens de Eerste Wereldoorlog werkte Maria Dickin CBE aan de verbetering van de vreselijke toestand van de diergezondheid in het Whitechapel gebied van Londen. Ze wilde een kliniek openen waar East Enders die in armoede leefden, gratis behandeling zou krijgen voor hun zieke en gewonde dieren. Links: Ondanks alle scepsis opende Maria Dickin haar vrije 'apotheek' in een kelder in Whitechapel op zaterdag 17 november 1917. Het was meteen een succes en ze werd al snel ge- dwongen om een groter pand te vinden. Foto PDSA. Binnen zes jaar had deze bijzondere vrouw haar eerste mobiele kliniek – door een paard getrokken - en weldra werd een vloot van zulke mobiele klinieken opgericht. Een PDSA voertuig werd al snel een troostend en ver- trouwd gezicht in het hele land. Met het succes kwam er ook kritiek van het Kon. -

Dickin Medal

No. Dogs Award Time PS 1 Kuga – Belgian Malinois 26 October 2018 Australian Army 2 Chips – Husky crossbreed 15 January 2018 US Army 3 Mali – Belgian Malinois 17 November 2017 Royal Army Veterinary Corps 4 Lucca - German Shepherd 5 April 2016 US Marine Corps 5 Diesel – Belgian Malinois 28 December 2015 - Royal Army Veterinary Corps, Arms and 6 Sasha – Labrador 21 May 2014 Explosives Search Royal Army Veterinary Corps, Arms and 7 Theo – Springer Spaniel 25 October 2012 Explosives Search Royal Army Veterinary Corps, Arms and 8 Treo – Labrador 24 February 2010 Explosives Search 9 Sadie – Labrador 6 February 2007 RAVC arms and explosive search dog 10 Lucky – German Shepherd 6 February 2007 RAF Police anti-terrorist tracke 11 Buster – Springer Spaniel 9 December 2003 Royal Army Veterinary Corps 12 Sam – German Shepherd 14 January 2003 Royal Army Veterinary Corps Salty and Roselle – Labrador 13 5 March 2002 - Guide dogs 14 Appollo – German Shepherd 5 March 2002 - 15 Gander – Newfoundland 27 October 2000 - 16 Tich – Egyptian Mongrel 1 July 1949 1st Battalion King’s Royal Rifle Corps 17 Antis – Alsatian 28 January 1949 - 18 Brian – Alsatian 29 March 1947 - 19 Ricky – Welsh Collie 29 March 1947 - Punch and Judy – Boxer dog 20 November 1946 - and bitch 21 Judy – Pedigree Pointer May 1946 - 22 Peter – Collie November 1945 - 23 Rip – Mongrel 1945 - 24 Sheila – Collie 2 July 1945 - 25 Rex – Alsatian April 1945 MAP Civil Defence Rescue Dog 26 Rifleman Khan – Alsatian 27 March 1945 147. 6th Battalion Cameronians (SR) 27 Thorn – Alsatian 2 March 1945 MAP Serving with Civil Defence 28 Rob – Collie 22 January 1945 Special Air Service 29 Beauty – Wire-Haired Terrier 12 January 1945 PDSA Rescue Squad 30 Irma – Alsatian 12 January 1945 MAP Serving with Civil Defence 31 Jet – Alsatian 12 January 1945 MAP Serving with Civil Defence 32 Bob – Mongrel 24 March 1944 6th Royal West Kent Regt No. -

Marsha Wells — Building For

tAPRIL 2008 Marsha Wells — Building for Big Shots of the Future Small Wonders By Shaun Hittle Lori Sims to Perform at The Gilmore Anything Musical Is Possible for Opus 21 Fixin’ of the Ivories Whale Sharks Highlight a Holbox Adventure $ # # ! " # % !!! ,1*0)+.41;2*161)4#2*; The Park Club building and cityscape, 2004 We invite you to join The Park Club and discover its unique history and rich tradition;where business and culture meet in the heart of downtown Kalamazoo. HISTORY The Park Club of Kalamazoo celebrated its 100th anniversary in 2004.The Club was originally located in the Balch home on the corner of Rose and South Streets. In the late 1920s, the growing club purchased the William S. Lawrence Queen Anne style mansion. Located right next door, it was built in 1898 and remains the Club’s home today. SERVICES The Park Club is a private, social dining club serving lunch and dinner daily, as well as providing meeting space, banquets and catering for its members.The twelve unique dining rooms offer a variety of settings to suit any occasion, from small and intimate personal affairs to corporate meetings and large gatherings of all kinds. MEMBERSHIP Our members and guests enjoy the finest in hand-crafted food, select wines and person- alized service in an historic setting.The Park Club offers several membership categories to suit various personal and professional levels of Club use and activity. Membership is open to men and women 21 years of age and over. We hope you will join us today. The Park Club A SECOND CENTURY OF EXCELLENCE www.parkclub.net (269) 381-0876 t 219 West South Street, Kalamazoo, Mich. -

WHAT the DICKIN(S)

WHAT THE DICKIN(s) 1 What is the Dickin Medal? Various Recipients Other Awards Animals in War Memorial, London 2 Maria Dickin (1870-1951) Maria Dickin CBE was a social reformer and an animal welfare pioneer. In 1917 she founded the People's Dispensary for Sick Animals (PDSA). • PDSA is a British veterinary charity which provides care for sick and injured animals of the poor. • PDSA is the UK’s leading veterinary charity. 3 Foundation and development During World War I, animal welfare pioneer Maria Dickin worked to improve the dreadful state of animal health in the Whitechapel area of London. She wanted to open a clinic where East Enders living in poverty could receive free treatment for their sick and injured animals. Despite widespread scepticism, she opened her free "dispensary" in a Whitechapel basement on Saturday 17 November 1917. It was an immediate success and she was soon forced to find larger premises. Within six years, Maria Dickin had designed and equipped her first horse-drawn clinic, and soon a fleet of mobile dispensaries was established. PDSA vehicles soon became a common sight throughout the country. Eventually, PDSA's role was defined by two Acts of Parliament, in 1949 and 1956, that continue to govern its activities today. 4 The Dickin Medal In 1943, the PDSA created the Dickin Medal and named it for Maria Dickin. It was initially to honour the work of animals in World War II. It is awarded to animals that have displayed "conspicuous gallantry or devotion to duty while serving or associated with any branch of the Armed Forces or Civil Defence Units". -

Mary of Exeter Dm 32 Pdsa Dickin Medal Mary of Exeter Dm 32

MARY OF EXETER DM 32 PDSA DICKIN MEDAL MARY OF EXETER DM 32 “For outstanding endurance on War Service in spite of wounds.” Date of Award: November 1945 ©Imperial War Museum CH 6860 MARY OF EXETER’S STORY Espionage has always gone hand in hand with conflict. During World War II, carrier pigeons were crucial weapons in the spy’s armoury and few distinguished themselves more notably than the ‘Indestructible Pigeon’, Mary of Exeter, (Pigeon No. NURP 40. WCE 249). Owned by bootmaker and pigeon breeder Cecil ‘Charlie’ Brewer, Mary of Exeter joined the National Pigeon Service in the 1940s. Her role was to provide critical intelligence to the Allies by delivering top secret messages from behind enemy lines. “SHE MANAGED TO MAKE IT THROUGH DESPITE THE HAWK’S ATTACK.” ©Imperial War Museum H 3048 Mary of Exeter completed four successful missions from France and, remarkably, managed to survive three German attempts to stop her delivering essential intelligence. Returning home from one mission, she was found to have suffered wounds to her neck and breast. The enemy kept specially trained hawks to attack carrier pigeons and she managed to make it through despite a hawk attack. Having recovered from her injuries, she returned to action two months later. Hawks were not the only method used to stop pigeons – they would shoot them as well. She returned from that mission with a missing wing tip and three shotgun pellets in her body. Nursed back to health by her owner, she once again returned to action following test flights. On her final mission, Mary of Exeter made it home with not just a vital message, but shrapnel injuries to her neck.