In Indonesia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Science Behind the Tobacco Heating System

The Science behind the Tobacco Heating System A Summary of Published Scientific Articles Maurice Smith, Christelle Haziza, Julia Hoeng, Frank Lüdicke, Serge Maeder, Patrick Vanscheeuwijck, Manuel C. Peitsch Philip Morris International Preamble very contemporary platform called sbvIMPROVER to foster the verification of both our methods and We recognize that cigarettes are a dangerous results by independent scientists. We have also product, and it is well known that the best way to recently launched an Investigator Initiated Study avoid the harms of smoking is never to start, or to program, a first step towards encouraging third quit. Nevertheless, based on the World Health parties to conduct studies with our RRPs. Organization’s own predictions, there will be more than one billion smokers by the year 2025. In this document, you will find a summary of our Therefore, alternative products that significantly scientific publications describing the assessment reduce the risk of disease compared with of THS2. If you have any comments or questions cigarette smoking are a fundamental complement about our science, be it about the methods we to the regulatory efforts aimed at reducing use or the results we have obtained, let us know. smoking prevalence. We look forward to hearing from you. WE HAVE BROUGHT TOGETHER OVER 300 WORLD- Prof. Manuel C. Peitsch CLASS SCIENTISTS FROM 30 FIELDS OF EXPERTISE – Chief Scientific Officer INCLUDING TOXICOLOGY, SYSTEMS BIOLOGY AND MEDICINE – TO DEVELOP AND ASSESS PRODUCTS Declaration of Interest THAT HAVE THE POTENTIAL TO REDUCE INDIVIDUAL RISK AND POPULATION HARM All studies presented and referenced in this COMPARED WITH SMOKING. document were fully funded by Philip Morris International. -

Smoking Behavior and the Use of Cigarette Types Among University Student

E-ISSN 2240-0524 Journal of Educational and Social Research Vol 10 No 5 ISSN 2239-978X www.richtmann.org September 2020 . Research Article © 2020 Arisona et.al.. This is an open access article licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/) Smoking Behavior and the Use of Cigarette Types Among University Student Amalia Arisona Laili Rahayuwati Ayu Prawesti Habsyah Saparidah Agustina Faculty of Nursing, Universitas Padjadjaran, Indonesia DOI: https://doi.org/10.36941/jesr-2020-0100 Abstract The number of smokers is increasing every year in Indonesia. Cigarettes can cause several health problems and can even cause death. Aside from conventional cigarettes, e-cigarettes and shisha are starting to get the spotlight. The types of cigarettes include conventional cigarettes, electric cigarettes and shisha can cause health problems to both smokers and the people around them. The purpose of this study was to determine smoking behavior and the use of cigarette types in students. This research was quantitative descriptive. The population in this study were students who have smoked either the conventional, electric or shisha. The sampling technique used was accidental sampling with 384 students as the samples. The instrument in this study used a questionnaire that was independently developed by researchers with a total of 14 questions. The results of the data obtained were then analyzed using descriptive analysis presented in the form of a percentage. Based on the results of the study it was found that non-health students (90.6%) were more likely to smoke than health students (9.4%). -

The Illicit Cigarette Trade in Indonesia

The Illicit Cigarette Trade in Indonesia Widya Kartika Rahmanda Muhammad Thaariq Dwi Rahayu Ningrum Herni Ramdlaningrum Luhur Fajar Martha Setyo Budiantoro 2019 The Illicit Cigarette Trade in Indonesia Authors: Widya Kartika, Rahmanda Muhammad Thaariq, Dwi Rahayu Ningrum, Herni Ramdlaningrum, Luhur Fajar Martha, Setyo Budiantoro ISBN: 978-623-91350-1-0 Researchers: Widya Kartika, Rahmanda Muhammad Thaariq, Dwi Rahayu Ningrum, Herni Ramdlaningrum, Setyo Budiantoro, Luhur Fajar Martha, Wildan Mukhallad, Fajrin Kurnia, Muhammad Fajar Rakhmadi Enumerators: Abd Haris Zainuddin, Adella Oktavia, Adik Saiful Yulianto Safikri, Ahmad Suratmi, Ali Zahid Habibullah, Anbeja Kirsy, Ardian Firmansyah, Dio Farhan Hudaya, Eka Damayanti, Gandi Vimala, Hadisaputra, Haekal Ghifari, Haikal Fadlan Mugits, Hudan Mahfudin Nursalim, Naufal Qowam, Nico Purwanto, Nohari, Ola Aldeva Fenchia, Prilly Putri Herdianti, Rachmat Affandi, Rachmat Ichsan, Rendhy Firmanzah, Rian Fiarno Dwi Cahyo, Rianto, Rizki Hendarji Putra, Sartika Sabani, Setyo Budi Purwono, Sipyanti, Sunardi, Thufeil Muhammad Tyansah Editor: Herni Ramdlaningrum Layout and Design: Bambang Nurjaman Published by: Perkumpulan PRAKARSA Jl. Rawa Bambu I Blok A No. 8E Pasar Minggu, Jakarta Selatan Daerah Khusus Ibukota Jakarta 12520 © 2019 Perkumpulan PRAKARSA EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This report presents Perkumpulan PRAKARSA’s findings on the illicit cigarette trade in Indonesia. The analysis in this report focuses on three aspects: the magnitude and demand for illicit cigarettes; factors that affect illicit cigarette consumption; and the price elasticity of demand of substitute cigarettes. The aims of the research are to measure the magnitude of the illicit cigarette trade in Indonesia from a consumer approach; determine factors that affect illicit cigarette consumption; analyze the possibility of increasing the price of cigarettes and the impact on the illicit cigarette trade; and to provide a transparent methodology. -

Seatca Packaging Design (25Feb2020)Web

No logos, colours, Pictorial health brand images or warnings used in promotional conjunction with information standardised packaging SMOKING CAUSES LUNG CANCER Pack surfaces in a standard colour Brand and product names in a standard colour and font 2020 Southeast Asia Tobacco Control Alliance Packaging Design Analysis to Support Standardised Packaging in the ASEAN Authors: Tan Yen Lian and Yong Check Yoon Editorial Team: Southeast Asia Tobacco Control Alliance Suggested citation: Tan YL. and Yong CY. (2020). Packaging Design Analysis to Support Standardised Packaging in the ASEAN, January 2020. Southeast Asia Tobacco Control Alliance (SEATCA), Bangkok. Thailand. Published by: Southeast Asia Tobacco Control Alliance (SEATCA) Thakolsuk Place, Room 2B, 115 Thoddamri Road, Dusit, Bangkok 10300 Thailand Telefax: +66 2 241 0082 Acknowledgment We would like to express our sincere gratitude to our country partners for their help in purchasing the cigarette packs from each country for the purpose of the study, which contributed to the development of this report. Disclaimer The information, ndings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reect the views of the funding organization, its sta, or its Board of Directors. While reasonable eorts have been made to ensure the accuracy of the information presented at the time of publication, SEATCA does not guarantee the completeness and accuracy of the information in this document and shall not be liable for any damages incurred as a result of its use. Any factual errors or omissions are unintentional. For any corrections, please contact SEATCA at [email protected]. © Southeast Asia Tobacco Control Alliance 2020 This document is the intellectual property of SEATCA and its authors. -

AG FDA Comment Re Deeming Regulations

August 8, 2014 Division of Dockets Management (HFA-305) Food and Drug Administration 5630 Fishers Lane, Room 1061 Rockville, MD 20852 Re: Docket No. FDA–2014–N–0189: Deeming Tobacco Products to Be Subject to the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act, as Amended by the Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act; Regulations on the Sale and Distribution of Tobacco Products and Required Warning Statements for Tobacco Products The undersigned state attorneys general (hereinafter “the attorneys general”) submit this Comment in response to the Food and Drug Administration’s (FDA) Notice of Proposed Rule, 79 Fed. Reg. 23142 (April 25, 2014), to support the FDA’s proposed rule deeming certain tobacco products to be subject to the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (FD&C Act), as amended by the Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act (Tobacco Control Act).1 We support the FDA’s Proposed Rule, but also propose that the FDA take additional steps within its authority under the FD&C Act as appropriate for the protection of the public health and, in particular, to protect youth from the dangers of tobacco use. I. INTRODUCTION AND SUMMARY OF RECOMMENDATIONS State attorneys general have long fought to protect their citizens, particularly youth, from the dangers of tobacco products. For example, every state attorney general sued the major tobacco companies for the harm their products caused, and, as a result, reached settlement agreements, including the 1998 Master Settlement Agreement (MSA) that placed restrictions on the advertising, marketing, and promotion of those products. The MSA, entered into between 46 states and six other jurisdictions and the major cigarette manufacturers and numerous smaller manufacturers, committed the parties to “reducing underage tobacco use by discouraging such use and by preventing Youth access to Tobacco Products.” MSA § I. -

“The Harvest Is in My Blood” Hazardous Child Labor in Tobacco Farming in Indonesia WATCH SUMMARY

H U M A N R I G H T S “The Harvest is in My Blood” Hazardous Child Labor in Tobacco Farming in Indonesia WATCH SUMMARY HUMAN RIGHTS WATCH | MAY A boy’s hands after harvesting tobacco leaves on a farm near Sampang, East Java. “When we’re harvesting, I often feel sick because of the smell of the wet tobacco leaves, and I get a strong headache…. Sometimes it’s hard to breathe when there’s a lot of tobacco leaves near me. I can’t describe it. I get such a headache. I’m dizzy. I see stars, and everything just looks bright.” “R ,” 14, S , E J 4 “THE HARVEST IS IN MY BLOOD” Ayu is a petite, soft-spoken 13-year-old girl from a village near Garut, in the mountains of West Java, Indonesia.1 She is one of five children in her family, and her parents are farmers who cultivate tobacco and other crops on a small plot of land. “Since I was a kid, I’ve been going to the fields,” she said. “My parents plant tobacco. Mostly I help my parents and sometimes my neighbors. I have an older sister, an older brother, and two younger siblings. They help too.” Ayu is in her first year of junior high school, and she mostly helps on the farm outside of school—early in the morning before classes, in the afternoons, and on weekends and holidays. But she told Human Rights Watch she occasionally missed school to work in tobacco farming. “My mom asked me to skip school last year when it was the harvest,” she said. -

Tobacco and Kretek: Indonesian Drugs in Historical Change Arnez, Monika

www.ssoar.info Tobacco and Kretek: Indonesian drugs in historical change Arnez, Monika Veröffentlichungsversion / Published Version Zeitschriftenartikel / journal article Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Arnez, M. (2009). Tobacco and Kretek: Indonesian drugs in historical change. ASEAS - Austrian Journal of South-East Asian Studies, 2(1), 49-69. https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-362761 Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer CC BY-NC-ND Lizenz This document is made available under a CC BY-NC-ND Licence (Namensnennung-Nicht-kommerziell-Keine Bearbeitung) zur (Attribution-Non Comercial-NoDerivatives). For more Information Verfügung gestellt. Nähere Auskünfte zu den CC-Lizenzen finden see: Sie hier: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/deed.de ASEAS 2 (1) Monika Arnez - Tobacco and Kretek: Indonesian Drugs in Historical Change Aktuelle Südostasienforschung / Current Research on South-East Asia Tobacco and Kretek: Indonesian Drugs in Historical Change Monika Arnez1 University of Hamburg, Germany / Universität Hamburg, Deutschland ASEAS - Österreichische Zeitschrift für Südostasienwissenschaften / Austrian Journal of South-East Asian Studies SEAS - Gesellschaft für Südostasienwissenschaften / Society for South-East Asian Studies - www.SEAS.at The clove cigarettes (kretek) industry is the second largest employer in Indonesia, after the Indonesian government. Between 4 and 17 million people are employed in this industry, including areas such as cultivation, trading, transport, advertisement and production of clove cigarettes. The Indonesian government depends on the kretek industry because of its important economic function. This paper contributes to tracing the historical development of kretek, considering economic, social and political aspects. -

Marketing Work on Indonesia's Retail Infrastructure

The architecture of cigarette circulation: marketing work on Indonesia’s retail infrastructure Marina Welker Cornell University The cigarette industry mobilizes independent retail as the scaffolding for ubiquitous cigarette advertising and sales in Indonesia, forming an expansive semiotic and material architecture of cigarette circulation in a country with limited tobacco regulations. As impending regulations threaten to curb cigarette advertising, and independent retailers face stiff competition from mushrooming chain convenience stores, Philip Morris International’s Indonesian subsidiary has developed a retail community programme to recruit and ‘modernize’ select retailers. The programme has intensified the quotidian labour of marketers who use knowledge, persons, and things to inhabit and renovate independent retail. I show how fashioning cigarette markets entails fashioning retail infrastructure, and is embedded in intimate relations of power, care, and violence. On the Indonesian island of Lombok, I spent a day in the company of Pak Arif,1 a cigarette marketing contractor. At one of our stops, the rather taciturn woman running a small general store pointed out that during a recent storm the ‘sunscreen’ advertising Marlboro lights had blown on top of the awning to which it was attached, and was no longer performing its function of hailing potential smokers. Arif’s stepladder was too short for the job of restoring it to its proper position. Improvising, he manoeuvred his vehicle to the edge of the roof, using the stepladder to clamber -

Establishing a Community-Based Smoke-Free Homes Movement in Indonesia

Research Paper Tobacco Prevention & Cessation Establishing a community-based smoke-free homes movement in Indonesia Retna Siwi Padmawati1,2, Yayi Suryo Prabandari1,2, Tutik Istiyani2, Mark Nichter3, Mimi Nichter3 ABSTRACT INTRODUCTION Indonesia has one of the highest male smoking rates in the world (67%) and secondhand smoke (SHS) exposure occurs in over 70% of households. To date, AFFILIATION little research has investigated community recognition of the harms of secondhand 1 Department of Health smoke and support for a smoke-free homes (SFH) policy. This work discusses Behavior, Environment and Social Medicine, Faculty of the development and implementation of a community-based SFH intervention Medicine, Public Health and attempting to establish SFH as a new social norm. Nursing, Universitas Gadjah METHODS Research was conducted in Yogyakarta, Java. A proof-of-concept study Mada, Yogyakarta, Indonesia 2 Center for Health Behavior ascertained the feasibility of mounting a community-based SFH initiative in urban and Promotion, Faculty of neighborhoods. Educational materials on SHS were developed and pretested. An Medicine, Public Health and Nursing, Universitas Gadjah intervention was piloted and evaluated in the homes of 296 smokers residing in 4 Mada, Yogyakarta, Indonesia communities. Health educators and community health volunteers were trained to 3 School of Anthropology, University of Arizona, Tucson, implement SFH. Arizona, United States RESULTS Prior to the intervention, 11% of smokers did not smoke inside their home; post-intervention 54% of smokers did not smoke inside their home. The Yogyakarta CORRESPONDENCE TO Mimi Nichter. School of District Health Office has supported large scale implementation of smoke-free Anthropology, University of homes. -

Designing a Smoke-Free Future

Designing a Smoke-Free future How long will the world’s leading cigarette company be in the cigarette business? We’ve built the world’s most successful cigarette company, with the world’s most popular and iconic brands. Now we’ve made a dramatic decision. We will be far more than the leading cigarette company. We’re building PMI’s future on smoke-free products that are a much better choice than cigarette smoking. Indeed, our vision – for all of us at PMI – is that these products will one day replace cigarettes. Why are we doing this? Because we should... We understand the millions of men and women who smoke cigarettes. They are looking for less harmful, yet satisfying, alternatives to smoking. We will give them that choice. We have a commitment to our employees and our shareholders. We will fulfill that commitment by pursuing this long-term vision for success. Society expects us to act responsibly. And we are doing just that by designing a smoke- free future. ... and because we now can. Success in the cigarette business gives us the resources to pursue our ambitious vision. Thanks to the imagination and perseverance of thousands of people at PMI, we have developed breakthrough products that are smoke-free and enjoyable. And, we are selling them today. Over a million people have already given up smoking and switched to our new products, and this is just the beginning. We’re investing to make these products the Philip Morris icons of the future. A future PMI that’s known for replacing cigarettes with a portfolio of revolutionary products. -

A Systematic Literature Review on the Potential of Other Tobacco

International Journal of Pharma Research and Health Sciences, 2021; 9 (1): 3270-3279 DOI:10.21276/ijprhs.2021.01.02 Oktavia EP et al. CODEN (USA)-IJPRUR, e-ISSN: 2348-6465 Review Article A Systematic Literature Review on the Potential of Other Tobacco Processing Products (HPTL) as an Alternative Product in Tobacco Harm Reduction Oktavia Eka Puspita*, Tamara Gusti Ebtavanny, Nurus Sobah Department of Pharmacy, Faculty of Medicine, Brawijaya University, Malang 65145, East Java, Indonesia. ARTICLE INFO: ABSTRACT: Received: 21 Dec 2020 Tobacco products other than cigarettes or alternative tobacco products have gained much Accepted: 12 Feb 2021 popularity and perceived as less risk product compared to conventional cigarettes. In Published: 28 Feb 2021 Indonesia, the product is known as Hasil Pengolahan Tembakau Lainnya (HPTL) or Other Tobacco Processing Products. Many studies have been done throughout the world and showed that the products have potential in reducing risk of tobacco use. As long as those Corresponding author * products have much variety in design neither device nor materials the result may be differ Oktavia Eka Puspita, between studies. In this systematic literature review aimed to answers some question Department of Pharmacy, Faculty concerning issues whether HPTL is less risk compared to conventional cigarettes and does of Medicine, Brawijaya University, HPTL able in helping smoker to quit smoking. We searched published articles relating to Malang 65145, East Java, HPTL harm reduction and smoking cessation. The parameters for harm reduction is assessed Indonesia. based on the biomarker of exposure (BoE) levels detected in breath, blood, and urine and E Mail: [email protected] also based on the cardiovascular marker measured in participant. -

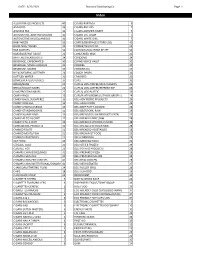

3/22/2021 Standard Distributing Co. Page 1 ALLIGATOR ICE

DATE: 3/22/2021 Standard Distributing Co. Page 1 Index ALLIGATOR ICE PRODUCTS 40 CIGARS-PARTAGA 6 ANTACIDS 33 CIGARS-PHILLIES 7 ARIZONA TEA 31 CIGARS-SWISHER SWEET 7 AUTOMOTIVE-ADDITIVES/FLUIDS 35 CIGARS-U.S. CIGAR 7 AUTOMOTIVE-MISCELLANEOUS 36 CIGARS-WHITE OWL 7 BABY NEEDS 33 COFFEE/BEVERAGE (STORE USE) 40 BAND AIDS/ SWABS 33 COFFEE/TEA/COCOA 23 BAR SUPPLIES 34 COLD/SINUS/ALLERGY RELIEF 33 BARBEQUE/HOT SAUCE 22 CONDENSED MILK 23 BATTERIES/FLASHLIGHTS 34 CONDOMS 34 BEVERAGE, CARBONATED 30 CONVENIENCE VALET 32 BEVERAGE, MISCELLANEOUS 31 COOKIES 20 BEVERAGE, MIXERS 30 COOKING OIL 23 BLEACH/FABRIC SOFTENER 24 COUGH DROPS 33 BOTTLED WATER 31 CRACKERS 20 BOWLS/PLATES/UTENSILS 37 CUPS 36 BREAD/BUNS 27 CUPS & LIDS-COFFEE/JAVA CLASSICS 36 BREAD/DOUGH MIXES 22 CUPS & LIDS-COFFEE/REFRESH EXP 36 CAKE/FROSTING MIXES 22 CUPS & LIDS-PLASTIC 36 CANDY-BAGS 15 CUPS/PLATES/BOWLS/UTENSILS(RESELL) 24 CANDY-BAGS, SUGARFREE 16 DELI-ADV PIERRE PRODUCTS 29 CANDY-KING SIZE 12 DELI-ASIAN FOOD 29 CANDY-MISCELLANEOUS 13 DELI-BEEF PATTY,COOKED 28 CANDY-STANDARD BARS 11 DELI-BEEF/PORK, RAW 28 CANDY-XLARGE BARS 13 DELI-BREAD/DOUGH PRODUCTS FRZN 29 CANDY-45 TO 10 CENT 12 DELI-BREADED BEEF,RAW 28 CANDY-5 TO 2 CENT 12 DELI-BREADED CHICKEN,COOKED 28 CANNABIDIOL PRODUCTS 32 DELI-BREADED CHICKEN,RAW 28 CANNED FRUITS 21 DELI-BREADED VEGETABLES 28 CANNED MEATS/FISH 21 DELI-BREAKFAST FOOD 29 CANNED VEGETABLES 21 DELI-CORNDOGS 29 CAT FOOD 23 DELI-MEXICAN FOOD 29 CEREALS, COLD 23 DELI-OTHER FROZEN 29 CEREALS, HOT 23 DELI-POTATO PRODUCTS 28 CHAMPS CHKN BOXES/BAGS 41 DELI-PREPARED