The Macro-Economic Impact of E-Commerce in the EU Digital Single Market

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Curious About Cryptocurrencies? Investors Need to Make Sure They Separate “Investing” from “Speculation” by Don Mcarthur, CFA®

Curious About Cryptocurrencies? Investors Need to Make Sure They Separate “Investing” from “Speculation” By Don McArthur, CFA® Bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies have received plenty of media coverage lately, and it is natural for investors to wonder about them. Even celebrities have become associated with Bitcoin publicity through social media. Interest has piqued to a point where there are even Exchange Traded Funds (ETFs) that invest in Bitcoin, giving investors the means to invest in the Futures market. After having performed in-depth research on Bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies, our position at Commerce Trust Company is that they should not currently play a role in client portfolios. As part of that research, Commerce Senior Vice President and Investment Analyst Don McArthur, CFA, put together a primer on the topic of cryptocurrencies in general. In the following commentary, he explains why Bitcoin at this stage is more about speculating than investing in something with intrinsic value. He also touches on how Blockchain networking technology not only supports cryptocurrencies, but many other industrial applications as well. We thought you would enjoy this commentary as McArthur shares his thoughts in a mind-opening Q&A. Q . What is Bitcoin and how did it start? A. Bitcoin is one of hundreds of digital currencies, or cryptocurrency, based on Blockchain technology. As an early mover, Bitcoin is by far the largest digital currency. Bitcoin was launched in 2009 by a mysterious person (or persons) known only by the pseudonym Satoshi Nakamoto. Unlike traditional currencies, which are issued by central banks, Bitcoin has no central monetary authority. -

New Insights on Retail E-Commerce (July 26, 2017)

U.S. Department of Commerce Economics Newand Insights Statistics on Retail Administration E-Commerce Office of the Chief Economist New Insights on Retail E-Commerce Executive Summary The U.S. Census Bureau has been collecting data on retail sales since the 1950s and data on e-commerce retail sales since 1998. As the Internet has become ubiquitous, many retailers have created websites and even entire divisions devoted to fulfilling online orders. Many consumers have By turned to e-commerce as a matter of convenience or to increase the Jessica R. Nicholson variety of goods available to them. Whatever the reason, retail e- commerce sales have skyrocketed and the Internet will undoubtedly continue to influence how consumers shop, underscoring the need for good data to track this increasingly important economic activity. In June 2017, the Census Bureau released a new supplemental data table on retail e-commerce by type of retailer. The Census Bureau developed these estimates by re-categorizing e-commerce sales data from its ESA Issue Brief existing “electronic shopping” sales data according to the primary #04-17 business type of the retailer, such as clothing stores, food stores, or electronics stores. This report examines how the new estimates enhance our understanding of where consumers are shopping online and also provides an overview of trends in retail and e-commerce sales. Findings from this report include: E-commerce sales accounted for 7.2 percent of all retail sales in 2015, up dramatically from 0.2 percent in 1998. July 26, 2017 E-commerce sales have been growing nine times faster than traditional in-store sales since 1998. -

E-Commerce Integration and Economic Development: Evidence from China∗

E-Commerce Integration and Economic Development: Evidence from China∗ Victor Couture,y Benjamin Faber,z Yizhen Gu§ and Lizhi Liu{ July 2017 –Preliminary and incomplete– Abstract The number of people buying and selling products online in China has grown from practically zero in 2000 to more than 400 million by 2015. Most of this growth has occurred in cities. In this context, the Chinese government recently announced the expansion of e-commerce to the countryside as a policy priority with the objective to close the rural-urban economic divide. As part of this agenda, the government entered a partnership with a large Chinese e-commerce firm. The program invests in the necessary transport logistics to ship products to and sell prod- ucts from tens of thousands of villages that were largely unconnected to e-commerce. The firm also installs an e-commerce terminal at a central village location, where a terminal manager assists households in buying and selling products through the firm’s e-commerce platform. This paper combines a new collection of survey and transaction microdata with a randomized control trial (RCT) across villages that we implement in collaboration with the e-commerce firm. We use this empirical setting to provide evidence on the potential of e-commerce inte- gration to foster economic development in the countryside, the underlying channels and the distribution of the gains from e-commerce across households and villages. Keywords: E-commerce, trade integration, economic development, rural-urban divide JEL Classification: F63, O12, R13 ∗We are grateful to CEGA, the Clausen Center, the Haas School of Business, the Weiss Family Fund and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation for providing funding for this study. -

Eliminating Barriers to Internal Commerce to Facilitate Intraregional Trade

Eliminating Barriers to Internal Commerce to Facilitate Intraregional Trade Olumide Taiwo and Nelipher Moyo, Brookings Africa Growth Initiative ncreased trade between African countries holds Roads account for 80 to 90 percent of all freight and promise for shared growth and development in passenger movement in Africa. Road density is an ef- the region. However, before African countries can fective proxy of how well connected areas of a country Ifully exploit the benefits associated with increased are. Africa has a road density of only 16.8 kilometers trade with each other, they must first address the bar- per 1,000 square kilometers, compared with 37 kilo- riers to the movement of goods and people within meters per 1,000 square kilometers in other low-in- their countries. It is difficult to imagine how Africa come regions (table 1). Likewise, rail density in Africa will be able to move goods from Cape Town to Cairo is only 2.8 kilometers per 1,000 square kilometers— when it is unable to move goods from one city to an- much lower than the 3.4 kilometers per 1,000 square other within the same country. Take the case of Ke- kilometers in other low-income regions. Air travel nya: while parts of northern Kenya were experiencing within Africa continues to be more expensive per mile major food shortages in January 2011, farmers in the than intercontinental travel. Africa’s inland waterways Rift Valley had food surpluses and were imploring the present an excellent opportunity to connect cities and government to buy their excess crops before they went countries. -

GLOSSARY of INTERNATIONAL TRADE TERMS 2016 Guide

CALIFORNIA FASHION ASSOCIATION 444 South Flower Street, 37th Floor · Los Angeles, CA 90071 ·ph. 213.688.6288 ·fax 213.688.6290 Email: [email protected] Website: www.californiafashionassociation.org GLOSSARY OF INTERNATIONAL TRADE TERMS 2016 Guide Sponsored By: Prepared by: CALIFORNIA FASHION ASSOCIATION 444 South Flower Street, 37th Floor, Los Angeles, CA 90071 Phone: 213-688-6288, Fax: 213-688-6290 [email protected] | www.californiafashionassociation.org 1 CALIFORNIA FASHION ASSOCIATION 444 South Flower Street, 37th Floor · Los Angeles, CA 90071 ·ph. 213.688.6288 ·fax 213.688.6290 Email: [email protected] Website: www.californiafashionassociation.org THE VOICE OF THE CALIFORNIA INDUSTRY The California Fashion Association is the forum organized to address the issues of concern to our industry. Manufacturers, contractors, suppliers, educational institutions, allied associations and all apparel-related businesses benefit. Fashion is the largest manufacturing sector in Southern California. Nearly 13,548 firms are involved in fashion-related businesses in Los Angeles and Orange County; it is a $49.3-billion industry. The apparel and textile industry of the region employs approximately 128,148 people, directly and indirectly in Los Angeles and surrounding counties. The California Fashion Association is the clearinghouse for information and representation. We are a collective voice focused on the industry's continued growth, prosperity and competitive advantage, directed toward the promotion of global recognition for the "Created in California" -

Digital Economy 2002

Digital Economy 2002 ECONOMICS AND STATISTICS U.S. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE ADMINISTRATION Economics and Statistics Administration DIGITAL ECONOMY 2002 ECONOMICS AND STATISTICS ADMINISTRATION Office of Policy Development AUTHORS Chapter I ................................................................................................................................ Lee Price [email protected] George McKittrick [email protected] Chapter II..................................................................................................................... Patricia Buckley [email protected] Sabrina Montes [email protected] Chapter III ........................................................................................................................... David Henry [email protected] Donald Dalton [email protected] Chapter IV ................................................................................................................... Jesus Dumagan [email protected] Gurmukh Gill [email protected] Chapter V ....................................................................................................................... Sandra Cooke [email protected] Chapter VI .................................................................................................................... Dennis Pastore [email protected] Chapter VII ........................................................................................................ Jacqueline Savukinas [email protected] -

A Glossary of Fiscal Terms & Acronyms

AUGUST7,1998VOLUME13,NO .VII A Publication of the House Fiscal Analysis Department on Government Finance Issues A GLOSSARY OF FISCAL TERMS & ACRONYMS 1998 Revised Edition Abstract. This issue of Money Matters is a resource document containing terms and acronyms commonly used by and in legislative fiscal committees and in the discussion of state budget and tax issues. The first section contains terms and abbreviations used in all fiscal committees and divisions. The remaining sections contain terms for particular budget categories and accounts, organized according to fiscal subject areas. This edition has new sections containing economic development, family and early childhood, and housing terms and acronyms. The other sections are revised and updated to reflect changes in terminology, particularly the human services section. For further information, contact the Chief Fiscal Analyst or the fiscal analyst assigned to the respective House fiscal committee or division. A directory of House Fiscal Analysis Department personnel and their committee/division assignments for the 1998 legislative session appears on the next page. Originally issued January 1997 Revised August 1998 House Fiscal Analysis Department Staff Assignments — 1998 Session Committee/Division Fiscal Analyst Telephone Room Chief Fiscal Analyst Bill Marx 296-7176 373 Capital Investment John Walz 296-8236 376 EDIT— Economic Development Finance CJ Eisenbarth Hager 296-5813 428 EDIT— Housing Finance Cynthia Coronado 296-5384 361 Environment & Natural Resources Finance Jim Reinholdz 296-4119 370 Education — Higher Education Finance Doug Berg 296-5346 372 K-12 Education Finance Greg Crowe 296-7165 378 Family & Early Childhood Finance Cynthia Coronado 296-5384 361 Health & Human Services Finance Joe Flores 296-5483 385 Judiciary Finance Gary Karger 296-4181 383 State Government Finance Helen Roberts 296-4117 374 Transportation Finance John Walz 296-8236 376 Taxes — Income, sales, misc. -

The South Carolina Innovation Plan

The South Carolina Innovation Plan January 2017 Table of Contents Introduction 3 Current State of Innovation 5 Innovation Economy and Sector Breakdown 9 Advanced Manufacturing 10 Computer Hardware and Software 11 Life Sciences and BioTechnology 12 Issues Analysis 13 Goals and Recommendations 16 Concluding Remarks 19 South Carolina Innovation Plan 2 Introduction Innovation. It is far easier said than done. South Carolina, The approach will be uniquely suited to South Carolina, at one time, managed to do it again and again. The state not simply an emulation of other states. South Carolina’s can claim the first round of golf in North America (played entrepreneurial potential, once recognized, must be in Charleston in 1786), the first submarine (the Hunley, cultivated to attract innovators who will start South from 1864), the first concoction of sweet tea (1890, in Carolina companies – continuously advancing the Summerville), the first city (Anderson) to have a knowledge, capabilities and prosperity of our citizens. continuous supply of electric power, the first electrically powered cotton gin (invented in 1897, also in Anderson), Strategic plans to attract cutting-edge companies are not and the first patented antibody labeling agent to diagnose new in South Carolina or elsewhere. However, even since infection (invented in 1912, in Columbia). Though a lull the most recent plan, in 2013, the state's condition has may have followed that string of successes, this Plan radically changed and improved. At that point, there were marks the return of Innovation – serious conversations about using being said and done – in South money from the state’s retirement Carolina. -

Challenges and Opportunities of the US Fishing Industry

Advancing Opportunity, Prosperity, and Growth WWW.HAMILTONPROJECT.ORG What’s the Catch? Challenges and Opportunities of the U.S. Fishing Industry By Melissa S. Kearney, Benjamin H. Harris, Brad Hershbein, David Boddy, Lucie Parker, and Katherine Di Lucido SEPTEMBER 2014 he economic importance of the fishing sector extends well beyond the coastal communities for which it is a vital industry. Commercial fishing operations, including seafood wholesalers, processors, and retailers, all contribute billions of dollars annually to the U.S. economy. Recreational fishing— Temploying both fishing guides and manufacturers of fishing equipment—is a major industry in the Gulf Coast and South Atlantic. Estimates suggest that the economic contribution of the U.S. fishing industry is nearly $90 billion annually, and supports over one and a half million jobs (National Marine Fisheries Service [NMFS] 2014). A host of challenges threaten fishing’s viability as an American industry. Resource management, in particular, is a key concern facing U.S. fisheries. Since fish are a shared natural resource, fisheries face traditional “tragedy of the commons” challenges in which the ineffective management of the resource can result in its depletion. In the United States, advances in ocean fishery management over the past four decades have led to improved sustainability, but more remains to be done: 17 percent of U.S. fisheries are classified as overfished (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration [NOAA] 2014), and even those with adequate fish stocks may benefit economically from more-efficient management structures. Meeting the resource management challenge can lead to improved economic activity and better sustainability in the future. -

Career Opportunities in Trade and Commerce

Career Opportunities in Trade and Commerce Trade policy is becoming an important issue to more businesses in the United States as the barriers to trade and capital movement decline and foreign markets become more interconnected with US markets. With the growth of regional trade blocks and increased membership in international trade organizations such as the World Trade Organization, the impact of US and foreign trade policy on the success of businesses in the United States will continue to increase. Trade policy directly affects virtually all industries. Trade policy and promotion includes a variety of activities including analysis of markets, increasing attendance at trade events, identifying agents and distributors, and disseminating information on export financing. Additional activities include representing business interests with officials of foreign governments, national government agencies, international organizations, and trade missions; identifying joint venture partners; researching development projects; and understanding foreign standards, testing, and certification requirements. Career Paths and Entry Salaries Entry-level titles include project coordinator, research assistant, government relations assistant, economic analyst, public relations specialist, and trade policy associate. A student with a graduate degree can expect a salary of $38,000 –$45,000, but professionals in the field emphasize that experience is key to both monetary and professional advancement. Communication between business and government is critical given that US government policies directly affect a company's international business. Government policies and legislation can affect international tariffs, non-tariff trade barriers, export financing, export license and control requirements, counter-trade, and technology transfer. Therefore, people who have held positions in the public sector have experience critical to a firm's international activities. -

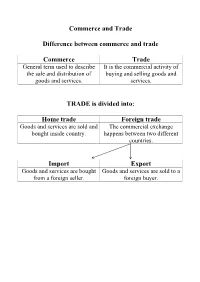

Commerce and Trade Difference Between Commerce and Trade

Commerce and Trade Difference between commerce and trade Commerce Trade General term used to describe It is the commercial activity of the sale and distribution of buying and selling goods and goods and services. services. TRADE is divided into: Home trade Foreign trade Goods and services are sold and The commercial exchange bought inside country. happens between two different countries. Import Export Goods and services are bought Goods and services are sold to a from a foreign seller. foreign buyer. FOUR CHANNELS OF DISTRIBUTION From manufacturer to consumers Manufacturer Wholesaler Retailer Consumer Chi produce Chi vende Chi vende al Consumatore all’ingrosso dettaglio 1. From the manufacturer to the consumer: the consumer buys goods and services directly from the producer, via Internet. 2. From the manufacturer to the consumer through a wholesaler, a business who buys large quantities of goods. 3. From the manufacturer to the consumer through a retailer, a business who buys small quantities of goods from wholesaler. 4. From the manufacturer to the consumer, via the retailer. FOUR FACTORS OF PRODUCTION They are essential to produce goods and services. Natural Labour Capital Entrepreneurship resources Risorse Forza Capitale Imprenditorialità naturali lavoro Water, It is based on To make Entrepreneur is a natural human goods and person who see forests, capital: services is opportunities for agricultural skills, necessary making a profit, lands, etc. education, investing producing goods and Omce they training and money in services that they are used up, experience. equipment, will sell. they cannot machinery, be replaced resources, easily. etc. THREE SECTORS OF PRODUCTION Primary sector Secondary sector Tertiary sector Involves the Takes the raw Involves the extraction and materials and provision of production of raw transforms them services to final materials (wood, into goods and consumers and coal, iron ore). -

Value of Data: There’S No Such Thing As a Free Lunch in the Digital Economy Wendy C.Y

Value of Data: There’s No Such Thing As A Free Lunch in the Digital Economy Wendy C.Y. Li (U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis)1,2 Makoto Nirei (University of Tokyo) Kazufumi Yamana (Kanagawa University) Date: October 15, 20183 Abstract The Facebook-Cambridge Analytica data scandal shows evidence that there is no such thing as a free lunch in the digital world. Online platform companies exchange “free” goods and services for consumer data, reaping potentially significant economic benefits by monetizing those data. Phrases such as “free goods” are misnomers. Welfare analysis on digital goods or services without considering the value of data can mislead policy analysis. In this research, we classify online platforms into eight major types based on underlying business models, and conduct case studies to analyze data activities related to each type. We show how online platform companies take steps to create the value of data, and present the data value chain to show how the value of data varies by step. We find that online platform companies can vary in the degree of vertical integration in the data value chain, and the variation can determine how they monetize their data and how much economic benefits they can capture. Unlike R&D that may depreciate due to obsolescence, data can produce new values through data fusion, a unique feature that can create unprecedented challenges in measurements. Our initial estimation shows that the value of data can be tremendous. Moreover, online platform companies can capture most benefits of the data, because they create the value of data and consumers lack knowledge to value their own data.