Mesic Prairie Communitymesic Abstract Prairie, Page 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Eleocharis Rostellata (Torr.) Torr., Is an Obligate Wetland Graminoid Species (Reed 1988)

United States Department of Agriculture Conservation Assessment Forest Service Rocky of the Beaked Spikerush Mountain Region Black Hills in the Black Hills National National Forest Custer, Forest, South Dakota and South Dakota May 2003 Wyoming Bruce T. Glisson Conservation Assessment of Beaked Spikerush in the Black Hills National Forest, South Dakota and Wyoming Bruce T. Glisson, Ph.D. 315 Matterhorn Drive Park City, UT 84098 Bruce T. Glisson is a botanist and ecologist with over 10 years of consulting experience, located in Park City, Utah. He has earned a B.S. in Biology from Towson State University, an M.S. in Public Health from the University of Utah, and a Ph.D. in Botany from Brigham Young University EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Beaked spikerush, Eleocharis rostellata (Torr.) Torr., is an obligate wetland graminoid species (Reed 1988). Beaked spikerush is widespread in the Americas from across southern Canada to northern Mexico, to the West Indies, the Caribbean, and the Andes of South America (Cronquist et al. 1994; Hitchcock et al. 1994). The species is secure throughout its range with a G5 ranking, but infrequent across most of the U.S., with Region 2 state rankings ranging from S1, critically imperiled; to S2, imperiled; to SR, reported (NatureServe 2001). Beaked spikerush is a “species of special concern” with the South Dakota Natural Heritage Program (Ode pers. comm. 2001). The only currently known population of beaked spikerush in South Dakota is in Fall River County, along Cascade Creek, an area where several other rare plant species occur. The beaked spikerush population is present on lands administered by Black Hills National Forest (BHNF), and on surrounding private lands, including the Whitney Preserve owned and managed by The Nature Conservancy (TNC). -

Burnett County Native Plant Lists Prairie/Upland Meadow

Burnett County Native Plant Lists Prairie/Upland Meadow Dry to medium soils Full sun 8 hours Common Scientific Flower Bloom Name Name Color Time Deer Height Waterfowl Butterflies Songbirds Game Birds Hummingbirds Small Mammals Reptiles/Amphibians Grasses Big bluestem ° Andropogon gerardii 3-8' NA NA ● ● ● ● ● Blue grama* Bouteloua gracilis 1-2' NA NA ● ● ● Bottlebrush grass Elymus hystrix 3' NA NA Canada wild rye Elymus canadensis 3-6' NA NA ● ● ● Indian grass ° Sorghastrum nutans 3-6' NA NA ● ● ● June grass* Koeleria macrantha 1-2' NA NA ● Schizachyrium Little bluestem* 2-3' NA NA ● ● ● scoparium Needle grass* Stipa spartea 3-4' NA NA ● ● ● Prairie dropseed* Sporobolus heterolepis 2-4' NA NA ● ● ● ● Side oats grama* Bouteloua curtipendula 2-3' NA NA ● ● ● Wildflowers Anise hyssop* Agastache foeniculum 2-4' Lavender June-Oct ● Bergamot* ° Monarda fistulosa 2-4' Lavender July-Aug ● ● ● ● Black-eyed Susan* Rudbeckia hirta 1-3' Yellow June-Oct ● Bush clover* Lespedeza capitata 3-4' Green July-Oct ● ● ● Butterfly weed* Asclepias tuberosa 2-3' Orange June-Sept ● Canada milk vetch Astragalus canadensis 2-3' White June-Aug ● ● ● Dotted mint Monarda punctata 1-3' Lavender June-Sept ● False sunflower* ° Heliopsis helianthoides 2-5' Yellow June-Oct ● Epilobium Fireweed 2-6' Pink June-Aug ● ● ● angustifolium Frost aster ° Aster pilosus 1-3' White Aug-Oct ● ● ● ● ● ● Harebell* ° Campanula rotundifolia 4-20" Purple June-Sept ● Heath aster Aster ericoides 6-36" White Aug-Oct ● ● ● ● ● ● Heart-leaf golden Zizia aptera 1-3' Yellow May-June ● alexander -

A POCKET GUIDE to Kansas Red Hills Wildflowers

A POCKET GUIDE TO Kansas Red Hills Wildflowers ■ ■ ■ ■ By Ken Brunson, Phyllis Scherich, Chris Berens, and Carl Jarboe Sponsored by Chickadee Checkoff, Westar Energy Green Team, The Nature Conservancy in Kansas, Kansas Grazing Lands Coalition and Comanche Pool Prairie Resource Foundation Published by the Friends of the Great Plains Nature Center Table of Contents • Introduction • 2 Blue/Purple ■ Oklahoma Phlox • 6 ■ Twist-flower • 7 ■ Blue Funnel-lily • 8 ■ Purple Poppy Mallow • 9 ■ Prairie Spiderwort • 10 ■ Purple Ground Cherry • 11 ■ Purple Locoweed • 12 ■ Stevens’ Nama • 13 ■ Woolly Locoweed • 14 Easter Daisy ■ Wedge-leaf Frog Fruit • 15 ©Phyllis Scherich ■ Silver-leaf Nightshade • 16 Cover Photo: Bush ■ Prairie Gentian • 17 Morning-glory ■ Woolly Verbena • 18 ©Phyllis Scherich ■ Stout Scorpion-weed • 19 Pink/Red ■ Rayless Gaillardia • 20 ■ Velvety Gaura • 21 ■ Western Indigo • 22 ■ Pincushion Cactus • 23 ■ Scarlet Gaura • 24 ■ Bush Morning-glory • 25 ■ Indian Blanket Flower • 26 ■ Clammy-weed • 27 ■ Goat’s Rue • 28 White/Cream Easter Daisy • 29 Old Plainsman • 30 White Aster • 31 Western Spotted Beebalm • 32 Lazy Daisy • 33 Prickly Poppy • 34 White Beardtongue • 35 Yucca • 36 White Flower Ipomopsis • 37 Stenosiphon • 38 White Milkwort • 39 Annual Eriogonum • 40 Devil’s Claw • 41 Ten-petal Mentzelia • 42 Yellow/Orange ■ Slender Fumewort • 43 ■ Bladderpod • 44 ■ Indian Blanket Stiffstem Flax • 45 Flower ■ Lemon Paintbrush • 46 ©Phyllis Scherich ■ Hartweg Evening Primrose • 47 ■ Prairie Coneflower • 48 ■ Rocky Mountain -

OLFS Plant List

Checklist of Vascular Plants of Oak Lake Field Station Compiled by Gary E. Larson, Department of Natural Resource Management Trees/shrubs/woody vines Aceraceae Boxelder Acer negundo Anacardiaceae Smooth sumac Rhus glabra Rydberg poison ivy Toxicodendron rydbergii Caprifoliaceae Tatarian hone ysuckle Lonicera tatarica* Elderberry Sambucus canadensis Western snowberry Symphoricarpos occidentalis Celastraceae American bittersweet Celastrus scandens Cornaceae Redosier dogwood Cornus sericea Cupressaceae Eastern red cedar Juniperus virginiana Elaeagnaceae Russian olive Elaeagnus angustifolia* Buffaloberry Shepherdia argentea* Fabaceae Leadplant Amorpha canescens False indigo Amorpha fruticosa Siberian peashrub Caragana arborescens* Honey locust Gleditsia triacanthos* Fagaceae Bur oak Quercus macrocarpa Grossulariaceae Black currant Ribes americanum Missouri gooseberry Ribes missouriense Hippocastanaceae Ohio buckeye Aesculus glabra* Oleaceae Green ash Fraxinus pennsylvanica Pinaceae Norway spruce Picea abies* White spruce Picea glauca* Ponderosa pine Pinus ponderosa* Rhamnaceae Common buckthorn Rhamnus cathartica* Rosaceae Serviceberry Amelanchier alnifolia Wild plum Prunus americana Hawthorn Crataegus succulenta Chokecherry Prunus virginiana Siberian crab Pyrus baccata* Prairie rose Rosa arkansana Black raspberry Rubus occidentalis Salicaceae Cottonwood Populus deltoides Balm-of-Gilead Populus X jackii* White willow Salix alba* Peachleaf willow Salix amygdaloides Sandbar willow Salix exigua Solanaceae Matrimony vine Lycium barbarum* Ulmaceae -

Verbena Stricta

JOURNAL OF THE HAMILTON NATURALISTS’ CLUB Volume 67 Number 7 March, 2014 © photo Joanne Redwood Birders head out into a “winter wonderland” at Kerncliff Park, Burlington, to conduct the Hamilton Christmas Bird Count on Boxing Day, December 26, 2013. This was shortly after the amazing ice storm on December 22. The ice and snow seriously affected numbers recorded. See article on page 148 – photo Joanne Redwood. In This Issue: Member Profile – Alan Wormington 2013 Hamilton Christmas Bird Count War on Science Northern Lights This Spring? HSA Bird Records for Fall Season 2013 Eastern Whip-poor-will Status in Ontario Hoary Vervain in the Hamilton Study Area Good News About Rainbow Darters at Crook’s Hollow Table of Contents Hamilton Christmas Bird Count - 26 December, 2013 Tom Thomas 148 Member Profile – Alan Wormington Bill Lamond 150 The Ontario Whip-poor-will Project with Audrey Heagy Michael Rowlands 152 Hoary Vervain (Verbena stricta) in the Hamilton Study Area Bill Lamond 153 Dates To Remember – March & April 2014 Liz Rabishaw/Fran Hicks 156 Noteworthy Bird Records – September - November 2013 Rob Dobos 158 And Now For Some Good News – Rainbows Instead of a Dam Bruce Mackenzie 159 Bumblebee Watch has Launched! Please Visit BumbleBeeWatch.org ----- 160 Trivia For Nature Jen Baker 160 Member’s Outing to the Short Hills Nature Sanctuary Jen Baker 160 Astronomy Corner – We Could See Northern Lights this Spring Mario Carr 165 Book Review – Rejecting Science in Canada Don McLean 166 Land’s Inlet Nature Project: Growing the Nature Corridor Jen Baker 167 Niagara Peninsula Hawkwatch Begins March 1st Gord McNulty 168 © photo Joanne Redwood Snowy Owl near Fifth Ave and Third Street, St Catharines This is certainly a good winter for Snowy Owls in the Hamilton area. -

Pollinator-Friendly Plants for the Northeast United States

Pollinator-Friendly Plants for the Northeast United States for more information on pollinators and outreach, please click here Information provided in the following document was obtained from a variety of sources and field research conducted at the USDA NRCS Big Flats Plant Materials Center. Sources of information can be found by clicking here. Pollinator rating values were provided by the Xerces Society as well as past and current research. The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination in all its programs and activities on the basis of race, color, national origin, age, disability, and where applicable, sex, marital status, familial status, parental status, religion, sexual orientation, genetic information, political beliefs, reprisal, or because all or a part of an individual’s income is derived from any public assistance program. (Not all prohibited bases apply to all programs.) Persons with disabilities who require alternative means for communication of program information (Braille, large print, audiotape, etc.) should contact USDA’s TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TDD). To file a complaint of discrimination write to USDA, Director, Office of Civil Rights, 1400 Independence Avenue, S.W., Washington, D.C. 20250- 9410 or call (800) 795-3272 (voice) or (202) 720-6382 (TDD). USDA is an equal opportunity provider and employer. USDA is committed to making its information materials accessible to all USDA customers and employees. Table of Contents Click on species to jump to that page • Purple Giant Hyssop • -

Verbena Stricta – Hoary Vervain

Friends of the Arboretum Native Plant Sale Verbena stricta – Hoary Vervain COMMON NAME: Hoary vervain, tall vervain, wooly verbena SCIENTIFIC NAME: Verbena stricta – Similar to the Latin name of a common European vervain and stricta meaning “upright” or “erect”. FLOWER: Blue-purple to pink tiny flowers tightly packed on pencil-like spikes. Each flower is about ¼ inch across with five spreading lobes. BLOOMING PERIOD: late June to early October SIZE: 1 to 4 feet tall BEHAVIOR: A vigorous, clump-forming annual or short-lived perennial. The flower spikes bloom from the bottom up. SITE REQUIREMENTS: Full sun and well-drained soil. Does best in poor soil. Will grow in rich loamy soil, but has difficulty competing with other plants. It is very drought resistant. NATURAL RANGE: It is found throughout most of the U.S. and eastern Canada except for California, Oregon and several Atlantic coastal states. In Wisconsin it is found in most parts except for the far northern counties. SPECIAL FEATURES: Flowers attract bees and butterflies. Four brown nutlets are produced per flower and are eaten by birds and small mammals. The leaves are egg-shaped or oval, 1 to 3 or more inches long. The leaves are host to the larval stage of several moths and butterflies, including the colorful common buckeye butterfly. The whole plant is covered with white hairs. SUGGESTED CARE: Easily grown in average, dry to medium well-drained soil. COMPANION PLANTS: Silky aster, bergamot, black-eyed Susan, butterfly weed, yellow coneflower, dwarf blazingstar, prairie smoke, prairie violet. . -

Suppressing Canada Thistle Establishment with Native Seed Mixes

SUPPRESSING CANADA THISTLE ESTABLISHMENT WITH NATIVE SEED MIXES AND RESULTING COST ANALYSIS A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the North Dakota State University of Agriculture and Applied Science By Steven Michael Fasching In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE Major Program: Natural Resources Management November 2012 Fargo, North Dakota North Dakota State University Graduate School Title Suppressing Canada Thistle Establishment With Native Seed Mixes And Resulting Cost Analysis By Steven Michael Fasching The Supervisory Committee certifies that this disquisition complies with North Dakota State University’s regulations and meets the accepted standards for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE SUPERVISORY COMMITTEE: Jack Norland 2/28/2013 Chair Edward Dekeyser 2/28/2013 Christina Hargiss 2/28/2013 Gary Clambey 2/28/2013 Approved: 2/28/2013 Frank Casey Date Department Chair ABSTRACT Canada thistle (Cirsium arvense) on conservation lands is costly and diminishes conservation objectives. This project was designed to control Canada thistle by spiking native seed mixtures. Spiking is where a native seed mixture had 3-5 native forbs that are functionally similar to Canada thistle at 3-10 times the recommended seeding density added to it. The project consisted of small-scale experiments on lands in eastern North Dakota and large-scale experiments on U.S. Fish and Wildlife land in eastern North and South Dakota. The results show that the spiked method reduced the establishment of Canada thistle immediately after seeding. The cost analysis showed the spike method was equal or lower in cost compared to herbicide control if herbicide control is: 1) 25% or less effective, 2) logistically problematic, 3) operationally more costly, 4) needed on two-thirds of the area, and 5) producing a high risk of affecting non-target species. -

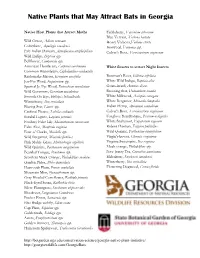

Native Plants to Attract Bats

Native Plants that May Attract Bats in Georgia Native Host Plants that Attract Moths Farkleberry, Vaccinium arboreum Blue Vervain, Verbena hastata Wild Onion, Allium cernuum Hoary Verbena,Verbena stricta Columbine, Aquilegia canadensis Ironweed, Vernonia spp. Pale Indian Plantain, Arnoglossum atriplicifolium Culver’s Root, Veronicastrum virginicum Wild Indigo, Baptisia spp. Bellflower, Campanula spp. American Hornbeam, Carpinus caroliniana White flowers to attract Night Insects Common Buttonbush, Cephalanthus occidentalis Rattlesnake Master, Eryngium yuccifolia Bowman's Root, Gillenia trifoliata Joe-Pye Weed, Eupatorium spp. White Wild Indigo, Baptisia alba Spotted Jo-Pye Weed, Eutrochium maculatum Goats-beard, Aruncus diocus Wild Geranium, Geranium maculatum Shooting Star, Dodecatheon meadia Smooth Ox Eye, Heliopsis helianthoides White Milkweed, Asclepias variegata Winterberry, Ilex verticillata White Bergamot, Monarda clinopodia Blazing Star, Liatris spp. Indian Hemp, Apocynum cannabium Cardinal Flower, Lobelia cardinalis Culver's Root, Veronicastrum virginicum Sundial Lupine, Lupinus perennis Foxglove Beardtongue, Penstemon digitalis Feathery False Lily, Maianthemum racemosum White Snakeroot, Eupatorium rugosum False Aloe, Manfreda virginica Robins Plantain, Erigeron pulchellus Four-o’ Clocks, Mirabilis spp. Wild Quinine, Parthenium integrifolium Wild Bergamot, Monarda fistulosa Virgin's-bower, Clematis virginiana Pink Muhly Grass, Muhlenbergia capillaris Virginia Sweetspire, Itea virginica Wild Quinine, Parthenium integrifolium Mock-orange, -

New Jersey Strategic Management Plan for Invasive Species

New Jersey Strategic Management Plan for Invasive Species The Recommendations of the New Jersey Invasive Species Council to Governor Jon S. Corzine Pursuant to New Jersey Executive Order #97 Vision Statement: “To reduce the impacts of invasive species on New Jersey’s biodiversity, natural resources, agricultural resources and human health through prevention, control and restoration, and to prevent new invasive species from becoming established.” Prepared by Michael Van Clef, Ph.D. Ecological Solutions LLC 9 Warren Lane Great Meadows, New Jersey 07838 908-637-8003 908-528-6674 [email protected] The first draft of this plan was produced by the author, under contract with the New Jersey Invasive Species Council, in February 2007. Two subsequent drafts were prepared by the author based on direction provided by the Council. The final plan was approved by the Council in August 2009 following revisions by staff of the Department of Environmental Protection. Cover Photos: Top row left: Gypsy Moth (Lymantria dispar); Photo by NJ Department of Agriculture Top row center: Multiflora Rose (Rosa multiflora); Photo by Leslie J. Mehrhoff, University of Connecticut, Bugwood.org Top row right: Japanese Honeysuckle (Lonicera japonica); Photo by Troy Evans, Eastern Kentucky University, Bugwood.org Middle row left: Mile-a-Minute (Polygonum perfoliatum); Photo by Jil M. Swearingen, USDI, National Park Service, Bugwood.org Middle row center: Canadian Thistle (Cirsium arvense); Photo by Steve Dewey, Utah State University, Bugwood.org Middle row right: Asian -

INTRODUCTION This Check List of the Plants of New Jersey Has Been

INTRODUCTION This Check List of the Plants of New Jersey has been compiled by updating and integrating the catalogs prepared by such authors as Nathaniel Lord Britton (1881 and 1889), Witmer Stone (1911), and Norman Taylor (1915) with such other sources as recently-published local lists, field trip reports of the Torrey Botanical Society and the Philadelphia Botanical Club, the New Jersey Natural Heritage Program’s list of threatened and endangered plants, personal observations in the field and the herbarium, and observations by other competent field botanists. The Check List includes 2,758 species, a botanical diversity that is rather unexpected in a small state like New Jersey. Of these, 1,944 are plants that are (or were) native to the state - still a large number, and one that reflects New Jersey's habitat diversity. The balance are plants that have been introduced from other countries or from other parts of North America. The list could be lengthened by hundreds of species by including non-persistent garden escapes and obscure waifs and ballast plants, many of which have not been seen in New Jersey since the nineteenth century, but it would be misleading to do so. The Check List should include all the plants that are truly native to New Jersey, plus all the introduced species that are naturalized here or for which there are relatively recent records, as well as many introduced plants of very limited occurrence. But no claims are made for the absolute perfection of the list. Plant nomenclature is constantly being revised. Single old species may be split into several new species, or multiple old species may be combined into one. -

Vascular Plants of the Forest River Bi- Ology Station, North Dakota

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln The Prairie Naturalist Great Plains Natural Science Society 6-2015 VASCULAR PLANTS OF THE FOREST RIVER BI- OLOGY STATION, NORTH DAKOTA Alexey Shipunov Kathryn A. Yurkonis John C. La Duke Vera L. Facey Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tpn Part of the Biodiversity Commons, Botany Commons, Ecology and Evolutionary Biology Commons, Natural Resources and Conservation Commons, Systems Biology Commons, and the Weed Science Commons This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Great Plains Natural Science Society at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Prairie Naturalist by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. The Prairie Naturalist 47:29–35; 2015 VASCULAR PLANTS OF THE FOREST RIVER BI- known to occur at the site. Despite this effort, 88 species OLOGY STATION, NORTH DAKOTA—During sum- in La Duke et al. (unpublished data) are not yet supported mer 2013 we completed a listing of the plant species of the with collections, but have been included with this list. No- joint University of North Dakota (UND) Forest River Biol- menclature and taxon concepts are given in the accordance ogy Station and North Dakota Game and Fish Department with USDA PLANTS database (United States Department of Wildlife Management Area (FRBS).The FRBS is a 65 ha Agriculture 2013), and the Flora of North America (Flora of tract of land that encompasses the south half of the SW ¼ of North America Editorial Committee 1993). section 11 (acquired by UND in 1952) and the north half of We recorded 498 plant species from 77 families in the the NW ¼ of section 14 (acquired by UND in 1954) in Ink- FRBS (Appendix A), which is greater than the number of ster Township (T154N, R55W).