Isabel Paterson and the Idea of America / Stephen Cox

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Isabel Paterson, Rose Wilder Lane, and Zora Neale Hurston on War, Race, the State, and Liberty

SUBSCRIBE NOW AND RECEIVE CRISIS AND LEVIATHAN* FREE! “The Independent Review does not accept “The Independent Review is pronouncements of government officials nor the excellent.” conventional wisdom at face value.” —GARY BECKER, Noble Laureate —JOHN R. MACARTHUR, Publisher, Harper’s in Economic Sciences Subscribe to The Independent Review and receive a free book of your choice* such as the 25th Anniversary Edition of Crisis and Leviathan: Critical Episodes in the Growth of American Government, by Founding Editor Robert Higgs. This quarterly journal, guided by co-editors Christopher J. Coyne, and Michael C. Munger, and Robert M. Whaples offers leading-edge insights on today’s most critical issues in economics, healthcare, education, law, history, political science, philosophy, and sociology. Thought-provoking and educational, The Independent Review is blazing the way toward informed debate! Student? Educator? Journalist? Business or civic leader? Engaged citizen? This journal is for YOU! *Order today for more FREE book options Perfect for students or anyone on the go! The Independent Review is available on mobile devices or tablets: iOS devices, Amazon Kindle Fire, or Android through Magzter. INDEPENDENT INSTITUTE, 100 SWAN WAY, OAKLAND, CA 94621 • 800-927-8733 • [email protected] PROMO CODE IRA1703 Isabel Paterson, Rose Wilder Lane, and Zora Neale Hurston on War, Race, the State, and Liberty ✦ DAVID T. BEITO AND LINDA ROYSTER BEITO he ideals of liberty, individualism, and self-reliance have rarely had more enthusiastic champions than Isabel Paterson, Rose Wilder Lane, and Zora TNeale Hurston. All three were out of step with the dominant worldview of their times. They had their peak professional years during the New Deal and World War II, when faith in big government was at high tide. -

Markets Not Capitalism Explores the Gap Between Radically Freed Markets and the Capitalist-Controlled Markets That Prevail Today

individualist anarchism against bosses, inequality, corporate power, and structural poverty Edited by Gary Chartier & Charles W. Johnson Individualist anarchists believe in mutual exchange, not economic privilege. They believe in freed markets, not capitalism. They defend a distinctive response to the challenges of ending global capitalism and achieving social justice: eliminate the political privileges that prop up capitalists. Massive concentrations of wealth, rigid economic hierarchies, and unsustainable modes of production are not the results of the market form, but of markets deformed and rigged by a network of state-secured controls and privileges to the business class. Markets Not Capitalism explores the gap between radically freed markets and the capitalist-controlled markets that prevail today. It explains how liberating market exchange from state capitalist privilege can abolish structural poverty, help working people take control over the conditions of their labor, and redistribute wealth and social power. Featuring discussions of socialism, capitalism, markets, ownership, labor struggle, grassroots privatization, intellectual property, health care, racism, sexism, and environmental issues, this unique collection brings together classic essays by Cleyre, and such contemporary innovators as Kevin Carson and Roderick Long. It introduces an eye-opening approach to radical social thought, rooted equally in libertarian socialism and market anarchism. “We on the left need a good shake to get us thinking, and these arguments for market anarchism do the job in lively and thoughtful fashion.” – Alexander Cockburn, editor and publisher, Counterpunch “Anarchy is not chaos; nor is it violence. This rich and provocative gathering of essays by anarchists past and present imagines society unburdened by state, markets un-warped by capitalism. -

American Affairs

Amencan Tke Economic Record JULY, 1945 Summer Number Vol. VII, No. 3 Contents Review and Comment 121 Winds of Opinion 123 "Full Employment" and Freedom in America .. Virgil Jordan 125 The American Menace Garet Garrett 131 Battle of Britain C. T. Revere 138 Tke Future of Foreign Trade James J. Hill 140 Bold Brevities 142 The Right to Borrow E. A. Goldenweiser 143 Adrift on the Deficit Sea. James A. Farley 145 After the War A. P. Herbert 147 Demonstration by Mars Frank E. Hook 148 Books 151 A Kansan in Russia League of Nations Key to Our Planned World Now a World System of Planned Societies Monkey-gland Economics The Elusive Law of Wages Yalta Aftermath Isaac Don Levine 163 The Myth of the Mixed Economy Ludwig Mises 169 Deindustrializing Central Europe John Hubert 174 What Price a Planned Economy? Friedrich A. Hayek 178 Notable Excerpts 182 American Affairs is an extension of an earlier periodical publication, The Economic Record, as a quarterly journal devoted to the presentation of current thought and opinion on controversial questions. Its circulation is restricted to Associates of The Conference Board. Its pages are intention- ally open to views that provoke debate, and contributions are invited. The National Industrial Conference Board does not itself participate in controversy, and does not endorse any of the ideas presented. All that it does here is to acknowledge the integrity of the contributors and the good faith of their work. National Industrial Conference Board, Inc. 247 Park Avenue, New York 17, N. Y. American Affairs The Economic Record GARET GARRETT, Editor Copyright, 19$5, by JULY, 1945 National Industrial Conference Board, Inc. -

Libertarianism, Feminism, and Nonviolent Action: a Synthesis

LIBERTARIAN PAPERS VOL. 4, NO. 2 (2012) LIBERTARIANISM, FEMINISM, AND NONVIOLENT ACTION: A SYNTHESIS GRANT BABCOCK* I. Introduction MURRAY ROTHBARD’S CONTRIBUTION to libertarian ethics was to outline a theory prohibiting aggressive violence (1978, p. 27-30). The influence of Rothbard’s ethics,1 combined with a decades-long political alliance with conservatives based on anticommunism, has produced a debate within libertarian circles about whether libertarians qua libertarians must take positions against certain forms of repression that do not involve aggressive violence. The non-aggression principle is as good a libertarian litmus test as has been suggested. Often, the voices who levy allegations of non-aggressive (or at least not exclusively aggressive) oppression come from the political left, and have un-libertarian (read: aggressive) solutions in mind, even if they do not conceive of those solutions as violent. Despite these considerations, I do believe that libertarians qua libertarians are obligated to say something about the kind of non-aggressive oppression that these voices from the left have raised regarding issues including, but not limited to, race, class, gender, and sexual orientation. Making the case that libertarians have these obligations irrespective of their * Grant Babcock ([email protected]) is an independent scholar. My thanks to Robert Churchill, Matthew McCaffrey, Ross Kenyon, and two anonymous referees for their help and encouragement. The paper’s merits are largely a result of their influence; any remaining errors are my own. CITATION INFORMATION FOR THIS ARTICLE: Grant Babcock. 2012. “Libertarianism, Feminism, and Nonviolent Action: A Synthesis.” Libertarian Papers. 4 (2): 119-138. ONLINE AT: libertarianpapers.org. -

A Spontaneous Order

Digital Proofer A Spontaneous Order: A Spontaneous Order Authored by Christopher Chase ... 6.0" x 9.0" (15.24 x 22.86 cm) The Capitalist Case Black & White on White paper 292 pages For A Stateless Society ISBN-13: 9781512117271 ISBN-10: 1512117277 Please carefully review your Digital Proof download for formatting, grammar, and design issues that may need to be corrected. We recommend that you review your book three times, with each time focusing on a different aspect. Check the format, including headers, footers, page 1 numbers, spacing, table of contents, and index. 2 Review any images or graphics and captions if applicable. 3 Read the book for grammatical errors and typos. Once you are satisfied with your review, you can approve your proof and move forward to the next step in the publishing process. To print this proof we recommend that you scale the PDF to fit the size of your printer paper. CHASE RACHELS DEDICATION Copyright © 2015 Christopher Chase Rachels All rights reserved. ISBN-13: 978-1512117271 ISBN-10: 1512117277 This work is dedicated to my son, Micha Rachels. May he grow up with a Cover Photo by DAVID ILIFF. License: CC-BY-SA 3.0 free spirit, critical mind, and warm heart. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS CONTENTS I would like to first and foremost thank my wife, Michelle Ferris, Foreword … 6 for standing by my side as an active participant in the fight against tyranny. Her loving encouragement and support enabled me to see this project to its Introduction … 11 end. Stephan Kinsella’s mentorship was likewise invaluable in its relation to the precision and rigor of this book. -

Features Columns Departments

VOLUME 60, NO 3 APRIL 2010 Features 8 Legends of the Fall: The Real and Imagined Sources of Our Bubble Economy by Richard W.Fulmer 13 The End of Medicine: Not With a Bang, But a Whimper by Theodore Levy 17 A Health Insurance Criminal Pleads His Case by James L. Payne 19 The Wisdom of Nien Cheng by James A. Dorn 24 Botswana: A Diamond in the Rough by Scott Beaulier 27 The Improbable Prose of Nassim Nicholas Taleb by Robert P.Murphy Page 17 31 Government Moonshine by Michael Heberling 34 How Shall We Live? by Paul Cleveland and Art Carden Columns 4 Ideas and Consequences ~ Anti-Force is the Common Denominator by Lawrence W.Reed 15 Thoughts on Freedom ~ On the Rule of Law by Donald J. Boudreaux 22 Our Economic Past ~ Private Capital Consumption: Another Downside of the Wartime “Miracle of Production” by Robert Higgs 29 Peripatetics ~ Opaque by Design by Sheldon Richman 37 Give Me a Break! ~ Let’s Take the “Crony” Out of “Crony Capitalism” by John Stossel 47 The Pursuit of Happiness ~ ObamaCare and Unions Page 6 by Charles W.Baird Departments 2 Perspective ~ Murray Rothbard by Sheldon Richman 6 Government Must Stimulate to Avoid a 1937-Style Recession? It Just Ain’t So! by Ivan Pongracic, Jr. 39 Capital Letters Book Reviews 41 The Beautiful Tree by James Tooley Reviewed by Max Borders 42 Capitalism at Work: Business, Government, and Energy by Robert L. Bradley, Jr. Reviewed by Michael Beitler 43 Herbert Hoover Page 44 by William E. Leuchtenburg Reviewed by Jim Powell 44 End the Fed by Ron Paul Reviewed by George Leef Perspective Murray Rothbard Published by n 1946 the fledgling Foundation for Economic Educa- The Foundation for Economic Education Irvington-on-Hudson, NY 10533 tion published a pamphlet titled “Roofs Phone: (914) 591-7230; E-mail: [email protected] or Ceilings: The Current Housing Problem” www.fee.org I (www.tinyurl.com/cpluwy), a brief against rent control President Lawrence W.Reed written by two unknown young economists: Milton Fried- Editor Sheldon Richman man and George Stigler. -

Liberty's Belle Lived in Harlingen Norman Rozeff

Liberty's Belle Lived in Harlingen Norman Rozeff Almost to a person those of the "baby boomer" generation will fondly remember the pop- ular TV series, "Little House on the Prairie." Few, however, will have known of Rose Wilder Lane, her connection to this series, to Harlingen, and more importantly her ac- complishments. Rose Wilder Lane was born December 5, 1886 in De Smet, Dakota Territory. She was the first child of Almanzo and Laura Ingalls Wilder. Aha, this stirs a memory; isn't the latter the author of the "Little House on the Prairie" book series for children? Yes, indeed. Rose also lived the hardship life, similar to her mother's as portrayed on television. Be- fore the age of two she was sent away to her mother's parents for several months after her parents contracted diphtheria, then a deadly disease. In August 1889 she became a sister but only for the short period that her baby brother survived without ever being given a name. Rose was to have no other siblings. When a fire destroyed their home soon after the baby's death and repeated crop failures compounded the Wilder family miseries, the Wilders moved from the Dakotas to his parent's home in Spring Valley, Minnesota. In their search for a settled life and livelihood, the Wilders in 1891 went south to Westville, Florida to live with Laura's cousin Peter. Still unhappy in these surroundings, the family returned to De Smet in 1892 and lived in a rented house. Here Grandma Ingalls took care of Rose while Laura and Almanzo worked. -

New Deal Nemesis the “Old Right” Jeffersonians

SUBSCRIBE NOW AND RECEIVE CRISIS AND LEVIATHAN* FREE! “The Independent Review does not accept “The Independent Review is pronouncements of government officials nor the excellent.” conventional wisdom at face value.” —GARY BECKER, Noble Laureate —JOHN R. MACARTHUR, Publisher, Harper’s in Economic Sciences Subscribe to The Independent Review and receive a free book of your choice* such as the 25th Anniversary Edition of Crisis and Leviathan: Critical Episodes in the Growth of American Government, by Founding Editor Robert Higgs. This quarterly journal, guided by co-editors Christopher J. Coyne, and Michael C. Munger, and Robert M. Whaples offers leading-edge insights on today’s most critical issues in economics, healthcare, education, law, history, political science, philosophy, and sociology. Thought-provoking and educational, The Independent Review is blazing the way toward informed debate! Student? Educator? Journalist? Business or civic leader? Engaged citizen? This journal is for YOU! *Order today for more FREE book options Perfect for students or anyone on the go! The Independent Review is available on mobile devices or tablets: iOS devices, Amazon Kindle Fire, or Android through Magzter. INDEPENDENT INSTITUTE, 100 SWAN WAY, OAKLAND, CA 94621 • 800-927-8733 • [email protected] PROMO CODE IRA1703 New Deal Nemesis The “Old Right” Jeffersonians —————— ✦ —————— SHELDON RICHMAN “Th[e] central question is not clarified, it is obscured, by our common political categories of left, right, and center.” —CARL OGLESBY, Containment and Change odern ignorance about the Old Right was made stark by reactions to H. L. Mencken’s diary, published in 1989. The diary received M extraordinary attention, and reviewers puzzled over Mencken’s opposition to the beloved Franklin Roosevelt, to the New Deal, and to U.S. -

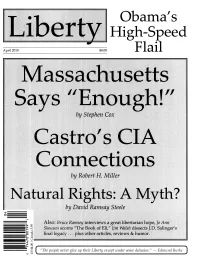

April 2010 Issue of Liberty Magazine

Obama's High-Speed April2010 $4.00 Flail Fresh from the Liberty Editors' Conference in Las Vegas! Editors Speak Out! Liberty's editors spoke to standing room only crowds (yet again!) at our con ference held in conjunction with FreedomFest in Las Vegas. Now you can buy digital-quality recordings ... How the New Deal Inspired the Libertarian Bailout: The Good, the Bad, and the Movement: David Boaz gets our conference Downright Ugly: Doug Casey, Randal off to an electric start witn his caRtivating O'Toole, Jo Ann Skousen, and Jim Walsh exploration of the roots of today s libertarian reveal the ugly truth about the biggest, most movement. (CD 0901A) blatant transfer of wealth in U.S. Fustory. Cui bono? Even if you aren't surprised, you11 be Liberty & Religion: Stephen Cox, Doug informed, fascInated, and appalled. Casey, Jo Ann Skousen, Andrew Ferguson, (CD 0909A) and Charles Murray discuss (and disagree about) God, church, state, morality, ana the Should We Abolish the Criminal Law?: individual. (CD 0902A) David Friedman makes a persuasive argument for one of the most provocative, How Urban Planners Caused the Housing seemingly impracticable ideas that you're Crisis: Randal O'Toole has a unique likely to hear. Our legal system has serious persrective on the cause of the economic problems, but can thIS be a solution? By the meltaown. Conventional wisdom aside; the end of the hour, you will be convinced the wealth of evidence he unveils leaves no doubt answer is "Yes!" (CD 0910A) that he's onto somethng. (CD 0903A) The Complete 2009 Liberty Conference: Market Failure Considered as an Argument Much more for less! Every minute of each of Against Government: David Friedman is these panels and presentations. -

Jennifer Burns, C.V., 1 of 18

Jennifer Burns, C.V., 1 of 18 JENNIFER BURNS [email protected] ACADEMIC POSITIONS Associate Professor of History, Stanford University, 2016-. Assistant Professor of History, Stanford University, 2012-2016. Assistant Professor of History, University of Virginia, 2007-2012. Lecturer, University of California, Berkeley, Department of History, 2005-2007. EDUCATION Ph.D. University of California, Berkeley, History, 2005. M.A. University of California, Berkeley, History, 2001. A.B. Harvard University, History, 1998, magna cum laude. PUBLICATIONS Book Goddess of the Market: Ayn Rand and the American Right (Oxford University Press, 2009). Select reviews: Jonathan Chait, The New Republic (September 23, 2009). Janet Maslin, The New York Times (October 22, 2009). Thomas Mallon, The New Yorker (November 9, 2009). Kimberly Phillips-Fein, Harper’s (December 2009). Charles Murray, Claremont Review of Books (Spring 2010). Elaine Showalter, Times Literary Supplement (June 2010). Corey Robin, The Nation (June 7, 2010). Catherine Rymph, Journal of American History 97 (December 2010): 854-855. Ruth Rosen, Reviews in American History 39 (March 2011):190-195. Patrick Allitt, Modern Intellectual History 8, (April 2011): 253-263. Kevin J. Smant, American Historical Review 116, (December 2011): 1521. Peer-Reviewed Articles and Chapters “The Three ‘Furies’ of Libertarianism: Rose Wilder Lane, Isabel Paterson, and Ayn Rand,” Journal of American History, Vol. 102, No. 3 (December 2015) : 746-774. “The Root of All Good: Ayn Rand’s Meaning of Money,” Journal of Cultural Economy, Vol. 4, No. 3 (August 2011) : 329-347. Reprinted in Brad Pasanek and Simone Polillo, Eds., Beyond Liquidity: The Metaphor of Money in Financial Crisis (New York: Routledge, 2013). -

Radical Reprints Roderick T. Long the Athenian Constitution

The Athenian Constitution: Government by Jury and Referendum Roderick T. Long Radical Reprints The Economics of Anarchy: A Study of the Industrial Type I have repeatedly been asked to write a brief sum- mary of the aims sought by Anarchists which could be read and discussed in the various clubs that are studying economic questions. With this end in view the following pages are submitted, trusting that they may be a help to those who are earnestly seeking the rationale of the Labor Question. — Dyer D. Lum. Available at: sonv.libertarianleft.org/distro/ Place your ad above — Email: [email protected] The Athenian Constitution: Government by Jury and Referendum ”Each single one of our citizens, in all the manifold aspects of life, is able to show himself the rightful lord and owner of his own person, and do this, moreover, with exceptional grace and exceptional versatility.” ~ Perikles (c. 495 - 429 BC) Athens: A Neglected Model Those engaged in the project of designing a constitution for a new libertarian nation can learn from the example of previous free or semi-free nations. In previous issues of Formulations we have accordingly surveyed sample consti- tutions ranging from the mediæval Icelandic system of competing assemblies to the U. S. Articles of Confederation. One example that is not often consid- ered when libertarians discuss constitutional design is ancient Athens. In a way this is not surprising. Athens in the fifth and fourth centuries BC is famous for being the purest, most extreme form of democracy in human history. Most libertarians get understandably nervous at the thought of unlim- ited majority rule. -

Libertarian Feminism in Britain, 1860-1910 Stephen Davies

LIBERTARIAN FEMINISM IN BRITAIN, 1860-1910 STEPHEN DAVIES CONTENTS Preface by Chris R. Tame and Johanna Faust Libertarian Feminism in Britain, 1860-1910 by Dr. Stephen Davies I The Origins II Organisational Origins III Some Publications IV The Suffrage Issue V The Female Employment Issue VI The Education Issue VII The Contagious Diseases Act VIII The Married Womens’ Property Act IX Other Involvements X The Ideological Character of Libertarian Feminism XI Critique of Society XII Historical Theory XIII Practical Proposals XIV The Historiography of Libertarian Feminism XV A Methodological Error XVI What Happened? XVII Conclusions A Selective Bibliography Some Comments on Stephen Davies’ Paper by Johanna Faust Libertarian Alliance Pamphlet No. 7 ISSN 0953-7783 ISBN 0 948317 98 1 A joint Libertarian Alliance/British Association of Libertarian Feminists publication. © 1987: Libertarian Alliance; British Association of Libertarian Feminists; Stephen Davies; Chris R. Tame; Johanna Faust. Stephen Davies is Lecturer in History at Manchester Polytechnic. He is a supporter of the British Association of Libertarian Feminists and also Treasurer of the Manchester Society. His Essays have appeared in a number of books and he has delivered papers to conferences of both the Libertarian Alliance and the Adam Smith Club. The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the British Association of Libertarian Feminists or the Libertarian Alliance. Libertarian Alliance 25 Chapter Chambers, Esterbrooke Street, London SW1P 4NN www.libertarian.co.uk email: [email protected] Director: Dr Chris R. Tame Editorial Director: Brian Micklethwait Webmaster: Dr Sean Gabb BRITISH ASSOCIATION OF LIBERTARIAN FEMINISTS 1 PREFACE by Chris R.