Peter Mango* Philosophy and Power in North

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter 4 the Right-Wing Media Enablers of Anti-Islam Propaganda

Chapter 4 The right-wing media enablers of anti-Islam propaganda Spreading anti-Muslim hate in America depends on a well-developed right-wing media echo chamber to amplify a few marginal voices. The think tank misinforma- tion experts and grassroots and religious-right organizations profiled in this report boast a symbiotic relationship with a loosely aligned, ideologically-akin group of right-wing blogs, magazines, radio stations, newspapers, and television news shows to spread their anti-Islam messages and myths. The media outlets, in turn, give members of this network the exposure needed to amplify their message, reach larger audiences, drive fundraising numbers, and grow their membership base. Some well-established conservative media outlets are a key part of this echo cham- ber, mixing coverage of alarmist threats posed by the mere existence of Muslims in America with other news stories. Chief among the media partners are the Fox News empire,1 the influential conservative magazine National Review and its website,2 a host of right-wing radio hosts, The Washington Times newspaper and website,3 and the Christian Broadcasting Network and website.4 They tout Frank Gaffney, David Yerushalmi, Daniel Pipes, Robert Spencer, Steven Emerson, and others as experts, and invite supposedly moderate Muslim and Arabs to endorse bigoted views. In so doing, these media organizations amplify harm- ful, anti-Muslim views to wide audiences. (See box on page 86) In this chapter we profile some of the right-wing media enablers, beginning with the websites, then hate radio, then the television outlets. The websites A network of right-wing websites and blogs are frequently the primary movers of anti-Muslim messages and myths. -

Administration of Donald J. Trump, 2019 Remarks At

Administration of Donald J. Trump, 2019 Remarks at the Conservative Political Action Conference in Oxon Hill, Maryland March 2, 2019 The President. Oh, thank you very much. Thank you very much. And thank you very much also to a man named Matt Schlapp. What a job he's done. And to CPAC—I actually started quite a while ago at CPAC and came here, probably made my first real political speech. And I enjoyed it so much that I came back for a second one, then a third. Then I said, what the hell, let's run for President. Right? But it's wonderful to be back with so many great patriots, old friends, and brave young conservatives. What a future you have. Our movement and our future in our country is unlimited. What we've done together has never been done in the history maybe of beyond of country, maybe in the history of the world. They came from the mountains and the valleys and the cities. They came from all over. And what we did in 2016—the election, we call it, with a capital "e"—it's never been done before. And we're going to do it, I think, again in 2020, and the numbers are going to be even bigger. Audience members. U.S.A.! U.S.A.! U.S.A.! The President. And we all had to endure, as I was running. So you had 17 Republicans, plus me. [Laughter] And I was probably more of a conservative than a Republican. People just didn't quite understand that. -

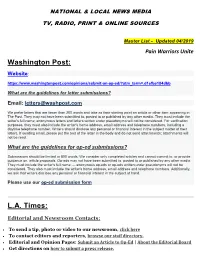

(Pdf) Download

NATIONAL & LOCAL NEWS MEDIA TV, RADIO, PRINT & ONLINE SOURCES Master List - Updated 04/2019 Pain Warriors Unite Washington Post: Website: https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/submit-an-op-ed/?utm_term=.d1efbe184dbb What are the guidelines for letter submissions? Email: [email protected] We prefer letters that are fewer than 200 words and take as their starting point an article or other item appearing in The Post. They may not have been submitted to, posted to or published by any other media. They must include the writer's full name; anonymous letters and letters written under pseudonyms will not be considered. For verification purposes, they must also include the writer's home address, email address and telephone numbers, including a daytime telephone number. Writers should disclose any personal or financial interest in the subject matter of their letters. If sending email, please put the text of the letter in the body and do not send attachments; attachments will not be read. What are the guidelines for op-ed submissions? Submissions should be limited to 800 words. We consider only completed articles and cannot commit to, or provide guidance on, article proposals. Op-eds may not have been submitted to, posted to or published by any other media. They must include the writer's full name — anonymous op-eds or op-eds written under pseudonyms will not be considered. They also must include the writer's home address, email address and telephone numbers. Additionally, we ask that writers disclose any personal or financial interest in the subject at hand. Please use our op-ed submission form L.A. -

Life, Liberty & Levin

MARK LEVIN FEATURES CONVENTION OF STATES FOR A FULL HOUR ON LIFE, LIBERTY & LEVIN he earliest ‘meeting of the “If you dig in, what you fi nd in Article V of the Constitution, minds’ to discuss Article V of historically is we have created which gives the people, acting the Constitution was when a structural problem. It’s not a through their state legislatures, Tthe Constitutional Convention met personnel issue,” Meckler said, power to call a Convention of in Philadelphia in 1787. In 2018, a “We’ve actually broken the structure States for the purpose of proposing similar meeting took place when of our government.” amendments to restrain Convention of States President government tyranny. Mark Meckler and former U.S. Sen. Coburn tried to correct the Senator Tom Coburn appeared on nation’s course in the Senate for ten Mark Levin pointed out, “Today Fox News Life, Liberty & Levin with years concluding, “What’s wrong the Supreme Court amends the long- time Article V Convention of with our country isn’t going to get Constitution, Congress passes States advocate Mark Levin. fi xed by the career politicians that are in the Senate or the House. So I For the full hour, these political left looking for another method with thought leaders discussed the state which we can cheat history and not “We need the decision-making of American politics and how to stop be a republic that falls. We need the process to be closer to the an overreaching government bent decision-making process to be closer people instead of unelected on our nation’s destruction. -

Download File

Tow Center for Digital Journalism CONSERVATIVE A Tow/Knight Report NEWSWORK A Report on the Values and Practices of Online Journalists on the Right Anthony Nadler, A.J. Bauer, and Magda Konieczna Funded by the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation. Table of Contents Executive Summary 3 Introduction 7 Boundaries and Tensions Within the Online Conservative News Field 15 Training, Standards, and Practices 41 Columbia Journalism School Conservative Newswork 3 Executive Summary Through much of the 20th century, the U.S. news diet was dominated by journalism outlets that professed to operate according to principles of objectivity and nonpartisan balance. Today, news outlets that openly proclaim a political perspective — conservative, progressive, centrist, or otherwise — are more central to American life than at any time since the first journalism schools opened their doors. Conservative audiences, in particular, express far less trust in mainstream news media than do their liberal counterparts. These divides have contributed to concerns of a “post-truth” age and fanned fears that members of opposing parties no longer agree on basic facts, let alone how to report and interpret the news of the day in a credible fashion. Renewed popularity and commercial viability of openly partisan media in the United States can be traced back to the rise of conservative talk radio in the late 1980s, but the expansion of partisan news outlets has accelerated most rapidly online. This expansion has coincided with debates within many digital newsrooms. Should the ideals journalists adopted in the 20th century be preserved in a digital news landscape? Or must today’s news workers forge new relationships with their publics and find alternatives to traditional notions of journalistic objectivity, fairness, and balance? Despite the centrality of these questions to digital newsrooms, little research on “innovation in journalism” or the “future of news” has explicitly addressed how digital journalists and editors in partisan news organizations are rethinking norms. -

The 2020 Election 2 Contents

Covering the Coverage The 2020 Election 2 Contents 4 Foreword 29 Us versus him Kyle Pope Betsy Morais and Alexandria Neason 5 Why did Matt Drudge turn on August 10, 2020 Donald Trump? Bob Norman 37 The campaign begins (again) January 29, 2020 Kyle Pope August 12, 2020 8 One America News was desperate for Trump’s approval. 39 When the pundits paused Here’s how it got it. Simon van Zuylen–Wood Andrew McCormick Summer 2020 May 27, 2020 47 Tuned out 13 The story has gotten away from Adam Piore us Summer 2020 Betsy Morais and Alexandria Neason 57 ‘This is a moment for June 3, 2020 imagination’ Mychal Denzel Smith, Josie Duffy 22 For Facebook, a boycott and a Rice, and Alex Vitale long, drawn-out reckoning Summer 2020 Emily Bell July 9, 2020 61 How to deal with friends who have become obsessed with 24 As election looms, a network conspiracy theories of mysterious ‘pink slime’ local Mathew Ingram news outlets nearly triples in size August 25, 2020 Priyanjana Bengani August 4, 2020 64 The only question in news is ‘Will it rate?’ Ariana Pekary September 2, 2020 3 66 Last night was the logical end 92 The Doociness of America point of debates in America Mark Oppenheimer Jon Allsop October 29, 2020 September 30, 2020 98 How careful local reporting 68 How the media has abetted the undermined Trump’s claims of Republican assault on mail-in voter fraud voting Ian W. Karbal Yochai Benkler November 3, 2020 October 2, 2020 101 Retire the election needles 75 Catching on to Q Gabriel Snyder Sam Thielman November 4, 2020 October 9, 2020 102 What the polls show, and the 78 We won’t know what will happen press missed, again on November 3 until November 3 Kyle Pope Kyle Paoletta November 4, 2020 October 15, 2020 104 How conservative media 80 E. -

How to Switch Programs on the XDS Pro Using Serial Commands Every

How to switch programs on the XDS Pro using Serial Commands Every Program transmitted via the XDS satellite system is associated with a Program ID that identifies the program to the receiver. Individual programs may be selected to the receiver’s output ports by issuing serial ID commands via the M&C (Console) Port on the back of the receiver, thereby changing the program that the receiver is decoding. If a program is selected for decoding using this method that is NOT part of the station’s list of authorized programming, it will NOT be decoded. Only programs authorized for the station that the receiver is assigned to can be decoded. Whenever possible, always use the XDS Port Scheduler as your main method of taking a program to ensure you receive the proper content. You can command the receiver as follows: 1) Start a terminal session (using HyperTerminal or equivalent) by connecting to the receiver’s M&C (Console) Port. The default settings for this Port are 115200, 8, None, 1. 2) Hit Enter. You should see a “Hudson” prompt. 3) Log in by by typing LOGIN(space)TECH(space)(PASSWORD) (Use your Affiliate NMS (myxdsreceiver.westwoodone.com) password OR you can use the receiver’s daily password (Setup > Serial # > PWD). 4) Login confirmation will be displayed (‘You are logged in as TECH’) Once you are logged in, the command to steer a Port on the receiver to a specific program PID is: PORT(space)LIVE,(Port),ID Examples: PORT LIVE,A,99 – This command will set Port A to Program ID 99 (Mark Levin) PORT LIVE,B,1196 – This command will set Port B to Program ID 1196 (CBS Sports - Tiki and Tierney) Please refer to the PID table listed below for the Program ID assignments for each program available on the Westwood One XDS receiver. -

Republican Establishment Now Seeking an Article V Constitutional Convention by Janine Hansen, Eagle Forum National Constitutional Issues Chairman

WARNING! Republican Establishment Now Seeking an Article V Constitutional Convention By Janine Hansen, Eagle Forum National Constitutional Issues Chairman The Passage of an Article V Constitutional Convention appears to have become the objective of “The Powers that Be” in the Republican Establishment. It is being bantered about as a way to overcome the “Trump” problem. The message seems to be, Don’t worry if Trump gets elected, we will take care of everything by having a “Convention of States.” Ted Cruz, Marco Rubio, and John Kasich have all recently stated publicly that they will now make the passage of an Article V so-called “Convention of States” their primary goal. Premier Neo Con and Establishment Republican William Kristol, Editor of the Weekly Standard, used his publication to promote Texas Governor Greg Abbott’s plan for an Article V Convention. Kristol is an important voice of the pro- internationalist/anti-American Sovereignty arm of the Republican Establishment. Also prominent conservative Republicans are promoting an Article V Constitutional Convention. http://www.weeklystandard.com/a-new- constitutional-convention/article/2000805 Texas Governor Greg Abbott has published his list of nine amendments. He made passage of a so-called “convention of states” a top priority at the Texas Republican State Convention last weekend. The Convention passed contradictory platform planks on Article V purposefully confusing the issue. This is especially true when one considers the “Convention of States” organization proposes unlimited structural changes which opens all the Articles of the Constitution to amendment through an Article V Constitutional Convention. There is no difference between an Article V Constitutional Convention and their so-called “convention of states.” The terminology of “convention of states” is found nowhere in Article V in the U.S. -

There Are Two Fundamental Reasons That Our Federal Government Has Far Exceeded Its Legitimate Authority Granted by the Terms of the Constitution

TESTIMONY OF MICHAEL FARRIS, JD, LLM HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES COMMONWEALTH OF PENNSYLVANIA There are two fundamental reasons that our federal government has far exceeded its legitimate authority granted by the terms of the Constitution. First, it is the nature of man to want to expand his own power. Second, the several states have never employed their constitutional authority to limit the size of the federal government. We should not be surprised that the federal government has continually expanded its power. When there are no checks on its power, not even the need to spend only the money that it has on hand, abuse of power is inevitable. George Mason was the delegate at the Constitutional Convention who best understood this propensity of government-all government-and he insisted that we create an effective check on this abuse of power. He said that when the national government goes beyond its power, as it surely will, we will need to place structural limitations on that exercise of power to stop the abuse. But, no such limitations would ever be proposed by Congress. History has proven him correct on both counts. But Mason's arguments led to the final version of Article V which gave the states the ultimate constitutional power-the power to unilaterally amend the Constitution of the United States, without the consent of Congress. The very purpose of the ability of the states to propose amendments to the Constitution was so that there would be a source of power to stop the abuse of power by the federal government. 1 It should seem self-evident that the federal abuse of power is pandemic. -

© Copyright 2020 Yunkang Yang

© Copyright 2020 Yunkang Yang The Political Logic of the Radical Right Media Sphere in the United States Yunkang Yang A dissertation submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2020 Reading Committee: W. Lance Bennett, Chair Matthew J. Powers Kirsten A. Foot Adrienne Russell Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Communication University of Washington Abstract The Political Logic of the Radical Right Media Sphere in the United States Yunkang Yang Chair of the Supervisory Committee: W. Lance Bennett Department of Communication Democracy in America is threatened by an increased level of false information circulating through online media networks. Previous research has found that radical right media such as Fox News and Breitbart are the principal incubators and distributors of online disinformation. In this dissertation, I draw attention to their political mobilizing logic and propose a new theoretical framework to analyze major radical right media in the U.S. Contrasted with the old partisan media literature that regarded radical right media as partisan news organizations, I argue that media outlets such as Fox News and Breitbart are better understood as hybrid network organizations. This means that many radical right media can function as partisan journalism producers, disinformation distributors, and in many cases political organizations at the same time. They not only provide partisan news reporting but also engage in a variety of political activities such as spreading disinformation, conducting opposition research, contacting voters, and campaigning and fundraising for politicians. In addition, many radical right media are also capable of forming emerging political organization networks that can mobilize resources, coordinate actions, and pursue tangible political goals at strategic moments in response to the changing political environment. -

Administration of Donald J. Trump, 2019 Digest of Other White House

Administration of Donald J. Trump, 2019 Digest of Other White House Announcements December 31, 2019 The following list includes the President's public schedule and other items of general interest announced by the Office of the Press Secretary and not included elsewhere in this Compilation. January 1 In the afternoon, the President posted to his personal Twitter feed his congratulations to President Jair Messias Bolsonaro of Brazil on his Inauguration. In the evening, the President had a telephone conversation with Republican National Committee Chairwoman Ronna McDaniel. During the day, the President had a telephone conversation with President Abdelfattah Said Elsisi of Egypt to reaffirm Egypt-U.S. relations, including the shared goals of countering terrorism and increasing regional stability, and discuss the upcoming inauguration of the Cathedral of the Nativity and the al-Fatah al-Aleem Mosque in the New Administrative Capital and other efforts to advance religious freedom in Egypt. January 2 In the afternoon, in the Situation Room, the President and Vice President Michael R. Pence participated in a briefing on border security by Secretary of Homeland Security Kirstjen M. Nielsen for congressional leadership. January 3 In the afternoon, the President had separate telephone conversations with Anamika "Mika" Chand-Singh, wife of Newman, CA, police officer Cpl. Ronil Singh, who was killed during a traffic stop on December 26, 2018, Newman Police Chief Randy Richardson, and Stanislaus County, CA, Sheriff Adam Christianson to praise Officer Singh's service to his fellow citizens, offer his condolences, and commend law enforcement's rapid investigation, response, and apprehension of the suspect. -

The Shrw Eagle

Volume 12 issue 4 APRIL 2019 THE SHRW EAGLE President SHRW APRIL LUNCHEON Michele Turner’s WHEN: APRIL 23, 2019 monthly message WHERE: Buckman’s Grille at Revere Golf Club, 2600 Hampton Rd. Henderson 89052 March was an exciting month. President Trump was exonerated!!! Wayne TIME: 11:30 am to 1:30 pm Allen Root was a wonderful speaker, telling us about his association with Doors open at 10:45 am President Trump. Member/Associate Price: $26 Important events this month: Legislative Day in Carson city – April 4th. Guests/Candidate Price: $31 NvFRW Spring Board meeting at South Point – April 12 & 13th. Please try to attend at least one. If you are a SHRW member & attend the Spring RESERVATION DEADLINE: Board meeting the club will reimburse you 50% of your ticket price Mail Payment (by 12 noon)-APR-18 Credit Card Payment (by 12 noon) SHRW is the largest club in the state, we need a good attendance. Friday via Eventbrite - APR-19 is the Executive Committee Meeting and NvFRW Regents meeting. If you https://www.eventbrite.com/o/ have questions regarding Regents, please call or email me, I have been a southern-hills-republican- Regent since 2005 when SHRW was formed. women-6818309391 The general meeting starts with Registration and Continental Breakfast Mail check/cash payments to: from 7 – 8:30 on Saturday, 4/13, followed by the general membership Southern Hills Republican Women meeting from 9am – 4pm. Need a ride or if you have more questions, 2505 Anthem Village Drive suite E-223 Henderson NV. 89052 please call or email me.