Mapping the Rise of Ubiquitous Connectivity from Myth to Market

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gates Scholar Newsletter

GATES SCHOLAR NEWSLETTER Volume 2 Issue 2 www.gatesscholar.org Autumn 2005/Spring 2006 HM THE QUEEN MEETS GATES SCHOLARS AT THE FITZWILLIAM HM The Queen meets Gates Scholars MUSEUM PERSPECTIVES ON THE FIRST INSTALMENT HM The Queen meeting Gates Scholars at the Fitzwilliam Museum, 8 June 2005. OF ORIENTATION 2005 Photos courtesy of Nigel Luckhurst 1–2 TRIPPING THE ROAD SCHOLASTIC 3 BRIDGING THE GAP BETWEEN SCIENCE AND POLICY 4 BIOVISION WORLD LIFE SCIENCES FORUM 5 AN UNLIKELY LINGUIST IN THE WORLD OF BRANDING L–R: Pierre Far, Anna King, Su-Yin Tan, Asbjorn 6 L–R: Alex Bremner, Sarah Dry, HM The Queen. Steglich-Petersen, HM The Queen, Mihai Brezeanu, FROM C TO SHINING C Dr Gordon Johnson, Moncef Tanfour. 7–8 SIMON & SHUSTER TO Perspectives on the first instalment PUBLISH LEVEY (’03) BOOK IN 2006 8 of orientation 2005 NEVER MIND: CAMBRIDGE Compiled by Paul Franklyn ALUMNI THAT THE WORLD FORGOT 9 Michael Dodson – explored the Peak District, one of the most RETHINKING Diploma in Computer beautiful parts of England (in my limited MULTICULTURALISM Science experience), hiking through the hills, going on 10–11 I love athletics. night walks to the pub (a mere 2 and a half Watching them is miles), canoeing, etc. Most importantly, DID YOU SAY enjoyable, simply out of however, I believe we had a distinct advantage “PALAEOBIOLOGY”? appreciation for the over other new graduate students coming to 12 effort and skill involved, Cambridge. By the beginning of the first week, but playing them is a NEWLY FORMED ALUMNI when everyone else is just showing up, we ASSOCIATION PLAYS much more fulfilling already had a large group of close friends for INTEGRAL ROLE experience. -

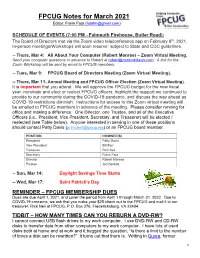

FPCUG Notes for March 2021 Editor: Frank Fota ([email protected])

FPCUG Notes for March 2021 Editor: Frank Fota ([email protected]) SCHEDULE OF EVENTS (7:00 PM - Falmouth Firehouse, Butler Road): The Board of Directors met via the Zoom video teleconference app on February 9th, 2021. In-person meetings/Workshops will soon resume; subject to State and CDC guidelines. -- Thurs, Mar 4: All About Your Computer (Robert Monroe) – Zoom Virtual Meeting. Send your computer questions in advance to Robert at [email protected]. A link for the Zoom Workshop will be sent by email to FPCUG members. -- Tues, Mar 9: FPCUG Board of Directors Meeting (Zoom Virtual Meeting). -- Thurs, Mar 11: Annual Meeting and FPCUG Officer Election (Zoom Virtual Meeting). It is important that you attend. We will approve the FPCUG budget for the new fiscal year, nominate and elect or reelect FPCUG officers, highlight the support we continued to provide to our community during the COVID-19 pandemic, and discuss the way ahead as COVID-19 restrictions diminish. Instructions for access to this Zoom virtual meeting will be emailed to FPCUG members in advance of the meeting. Please consider running for office and making a difference. One Director, one Trustee, and all of the Executive Officers (i.e., President, Vice President, Secretary, and Treasurer) will be elected / reelected (see Table below). Anyone interested in serving in one of these positions should contact Patty Davis ([email protected]) or an FPCUG board member. POSITION NOMINEE(S) President Patty Davis Vice President Bill Farr Treasurer Rick Neil Secretary Frank Fota Director Robert Monroe Trustee Jon Beckett -- Sun, Mar 14: Daylight Savings Time Starts -- Wed, Mar 17: Saint Patrick’s Day REMINDER – FPCUG MEMBERSHIP DUES Dues are due April 1, 2021, and cover the period from April 1 through March 31, 2022. -

Advertising Promotion and Other Aspects of Integrated Marketing

Advertising, Promotion, and other aspects of Integrated Marketing Communications Terence A. Shimp University of South Carolina Australia • Brazil • Japan • Korea • Mexico • Singapore • Spain • United Kingdom • United States Advertising, Promotion, & Other Aspects of © 2010, 2007 South-Western, Cengage Learning Integrated Marketing Communications, 8e Terence A. Shimp ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. No part of this work covered by the copyright hereon may be reproduced or used in any form or by any means—graphic, Vice President of Editorial, Business: electronic, or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, taping, Web Jack W. Calhoun distribution, information storage and retrieval systems, or in any other manner—except as may be permitted by the license terms herein. Vice President/Editor-in-Chief: Melissa S. Acuna Acquisitions Editor: Mike Roche Sr. Developmental Editor: Susanna C. Smart For product information and technology assistance, contact us at Cengage Learning Customer & Sales Support, 1-800-354-9706 Marketing Manager: Mike Aliscad Content Project Manager: Corey Geissler For permission to use material from this text or product, submit all requests online at www.cengage.com/permissions Media Editor: John Rich Further permissions questions can be emailed to Production Technology Analyst: Emily Gross [email protected] Frontlist Buyer, Manufacturing: Diane Gibbons Production Service: PrePressPMG Library of Congress Control Number: 2008939395 Sr. Art Director: Stacy Shirley ISBN 13: 978-0-324-59360-0 Internal Designer: Chris Miller/cmiller design ISBN 10: 0-324-59360-0 Cover Designer: Chris Miller/cmiller design Cover Image: Getty Images/The Image Bank South-Western Cengage Learning Permission Aquistion Manager/Photo: 5191 Natorp Boulevard Deanna Ettinger Mason, OH 45040 Permission Aquistion Manager/Text: USA Mardell Glinski Schultz Cengage Learning products are represented in Canada by Nelson Education, Ltd. -

Exploiting the Sound Symbolism of Proper Names

STANFORD UNIVERSITY Categorization by Character-Level Models: Exploiting the Sound Symbolism of Proper Names A thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Master of Science in Symbolic Systems by Joseph Robert Smarr Committee in charge: Professor Christopher D. Manning, Advisor, Primary Thesis Reader Professor Pat Langley, Second Thesis Reader Copyright © Joseph Robert Smarr 2003 All rights reserved. The Masters Thesis of Joseph Robert Smarr is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for a master’s project in Symbolic Systems. Primary thesis reader Secondary thesis reader TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract............................................................................................................................... v Acknowledgements............................................................................................................ vi Chapter 1: The challenge of unknown words............................................................... 1 1.1. Quantifying unknown words....................................................................... 1 1.2. The importance of recognizing proper noun phrases.................................. 4 1.3. Coping with unknown words...................................................................... 5 1.4. Can names be classified without context? .................................................. 6 Chapter 2: A probabilistic model of proper noun phrases............................................ 8 2.1. Formalization of problem .......................................................................... -

FPCUG Notes for March 2020 Editor: Frank Fota ([email protected])

FPCUG Notes for March 2020 Editor: Frank Fota ([email protected]) SCHEDULE OF EVENTS (7:00 PM - Falmouth Firehouse, Butler Road): -- Tues, Mar 3: Technology Workshop (Josh Cockey) -- Tues, Mar 10: Board of Directors (BoD) Meeting (Patty Davis, Presiding) -- Thu, Mar 12: Annual Meeting. The FPCUG Annual Meeting will be held at the Falmouth Volunteer Fire Department, 250 Butler Rd., Falmouth, VA 22405 on Thursday, March 12, 2020, at 7 PM. Please attend this meeting and consider running for office. You can make a difference! One Director, one Trustee, and all of the Executive Officers (i.e., President, Vice President, Secretary, and the Treasurer) will be elected or reelected at the meeting. Contact Patty Davis ([email protected]) or a BoD member if you are interested in serving in one of these positions. We will also accept nominations from FPCUG members at the meeting. The public is invited and refreshments will be served. -- Tues, Mar 17: All About Your Computer (Robert Monroe) -- Wed, Mar 18: Experimax Workshop – 1865-106 Carl D. Silver Parkway -- Thu, Mar 26: Windows All Workshop (Jim Hopkins) FEBRUARY GENERAL MEETING RECAP The FPCUG drew a small but enthusiastic crowd to view three TED talks: computer scientist Supasorn Suwajanakorn presented “Fake Videos of Real People -- and How to Spot Them,” Professor of Physics at TU Delft, Leo Kouwenhoven, discussed quantum computing, “Can we Make Quantum Technology work?” and Navin Reddy, CEO of the distance learning company Telusko, discussed “Blockchain: The Underrated Technology.” 1 SHARE A MONITOR WITH MULTIPLE COMPUTERS Dual monitor computer setups are all the rage these days. -

Central Florida Future, Vol. 35 No. 8, September 12, 2002

University of Central Florida STARS Central Florida Future University Archives 9-12-2002 Central Florida Future, Vol. 35 No. 8, September 12, 2002 Part of the Mass Communication Commons, Organizational Communication Commons, Publishing Commons, and the Social Influence and oliticalP Communication Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/centralfloridafuture University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the University Archives at STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Central Florida Future by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Recommended Citation "Central Florida Future, Vol. 35 No. 8, September 12, 2002" (2002). Central Florida Future. 1628. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/centralfloridafuture/1628 Thurs. Fri. Sat. Thunderstorms Thunderstorms Thunderstorms 88° 86° 88° 74° 75° 75° THE STUDENT NEW-SPAPER SERVING UCF SINCE 1968 Executive SGA designates $20,000 for controversial _speaker Senators old a re-vote after ed spending $20,000 - one-third of its that would bring Moor~ to UCF. annual speaker budget - to bring lib The bill, which passed 10-9, ini decision: backers leave the room eral activist, best-selling author and tially produced a 9-9 tie that was bro filmmaker Michael Moore to campus ken by student body Vice President BEN BAIRD next month. Brian Kirlew, who voted in favor of the STAFF WRITER The student senate meeting bill. Four senators abstained. back to the attracted a large crowd of members However; shortly after the mem In an unconventional voting from the Progressive Council - UCF's · bers of the Progressive Council left, process last Thursday; UCF's Student student activist coalition - who Goverriment Association recommend- classroom attended to publicly support the bill \ PLEASE SEE SGA ON 3 •\ ADAM ROSCHE STAFF WRITER UCF Provost and Vice President Gary Whitehouse will leave his administrative position by next• year and will return to No chads, but teaching. -

April 15Th May Have Been Shipped, but Loan from Atari in Return for Fewer Than 500 Were Sold Giving Them Access to the Lorraine Designs

market for a few weeks. By one mortgage on his house, and the estimate, as many as 2,560 dolls company obtained a $500,000 April 15th may have been shipped, but loan from Atari in return for fewer than 500 were sold giving them access to the Lorraine designs. Edison’s Doll The issue of which company April 15, 1890 First Round-the- owned the Lorraine chipsets quickly became a legal matter Thomas Edison’s [Feb 11] World Telephone between Atari and Amiga. It was "Phonograph Doll" was a actually mostly a proxy war children’s toy standing 22’ Call between ex-Commodore inches tall, weighing a founder Jack Tramiel [Jan 16] substantial four pounds, because April 15 (or 25), 1935 who had just bought Atari's of its porcelain head, jointed The first round-the-world Consumer Division [July 1], and wooden limbs, and most telephone call was made when Commodore who had recently importantly, a miniaturized Walter S. Gifford, president of acquired Amiga. phonograph embedded in its tin AT&T called T.G. Miller, a mere body. Its musical repertoire vice president. In fact both men included nursery rhymes, such were only around 50 feet apart, as “Jack and Jill” and “Mary Had in adjacent rooms at the Long LISP Unveiled a Little Lamb.” Lines Building in NYC, but their April 15, 1959 The doll had been developed conversation travelled across The LISP programming language back in 1877, but only went on some 23,000 miles. One of the was originally created by John sale today as part of Lenox phones was later preserved at McCarthy [Sept 4] as a Lyceum's electrical exhibition in the Smithsonian Institute. -

Trade Markedtm a Linguistic Introduction to Brand Naming By

Trade MarkedTM A linguistic introduction to brand naming by ERIC C. JACKSON April 2015 DEPARTMENT OF SLAVIC & EASTERN LANGUAGES AND LITERATURES PROGRAM IN LINGUISTICS BOSTON COLLEGE Table of Contents Abstract 1. Introduction…………………………………………………………………. 3 1.1 Branding — HUH! — What is it good for? 1.1.1. Fire-brands 1.1.2. Modern brands 1.2. Why study brands? 2. Phonology…………………………………………………………………… 7 2.1. Sound symbolism 2.1.1. Phýsei or thései? 2.1.2. Modern sound symbolism research 2.1.3. Explanations of sound symbolism 2.1.4. Sound symbolism and branding 2.2. Phonotactic constraints 2.3. Acronyms and initialisms 3. Morphology…………………………………………………………………18 3.1. The American Dream 3.1.1. Brandola 3.1.2. McBrands 3.1.3. Brand-O’s 3.2. “Pre-fixation” 3.2.1. eBrands 3.2.2. iBrands 3.2.3. abcBrands 3.3. “The killer advertising suffix” 4. Syntax………………………………………………………………………. 25 4.1. Compound names 4.2. Anthimeria 5. Semantics…………………………………………………………………… 27 5.1. Descriptive, suggestive, and arbitrary names 5.2. Store-brand sodas 5.3. Lost in translation 5.3.1. Automobile names 5.3.2. Cringeworthy in English 5.4. Naming in practice: An agricultural technology project 6. Conclusion…………………………………………………………………. 31 References — — Abstract This paper examines the practice of brand naming from a linguistic approach. Beginning with phonology in section 2, I discuss sound symbolism, a popular area of interest for professional namers, since consumers tend to exhibit surprising semantic perceptions of sound properties brand names. Section 3 analyzes brand names morphologically. In section 4 I briefly discuss the syntax of brands, and brand evolution in casual speech. -

200 North Vintage Lane Anaheim, CA 92805 714-349-1928 714-547

Objective: Work in the creative arenas of: Art Direction for large and small projects and programs. Creative Direction for marketing, merchandising and sales programs. Graphic Design for print, displays, packaging, web and promotions. Illustration for final use, storyboards and dimensional visualization. Dimensional Design for product development, packaging and displays. Corporate Identity programs and branding. 200 North Vintage Lane Experience: Anaheim, CA 92805 Over 30 years experience in designing, creating and implementing 714-349-1928 successful marketing and merchandising programs; packaging and product design; advertising, collateral and promotional programs. 714-547-1974 Fax 714-502-9365 Powerful design and illustration skills ranging from concept renderings for presentations and visualization, through final art for print or [email protected] mechanical reproduction and manufacture. Deep experience in Photoshop, InDesign, Illustrator and related graphics software. Several years of successful experience as a designer and manufacturer of displays and as a manufacturer and marketer of products sold in both retail and internet marketplaces. Copywriting experience in advertising, marketing and merchandising programs, branding, packaging and collateral programs. Highlighted Projects: Nissan: Designed a three part, high-end, standalone audio display to fit in with Nissan’s existing automotive showroom displays. Directed the prototype development and the manufacturing of over 1500 units. Chicken of the Sea: Given the design project of creating generic packaging for Albacore tuna that had been repackaged in oil, I identified a niche market in Italian delis that used Chunk Albacore Tuna for specific antipastos. I created packaging with an Italian chef on the front and antipasto recipes on the back of the label. -

The Language of Corporate Names: Historical, Social, and Linguistic Factors in the Evolution of Technology Corporation Naming Practices

UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI'I LiBRARY THE LANGUAGE OF CORPORATE NAMES: HISTORICAL, SOCIAL, AND LINGUISTIC FACTORS IN THE EVOLUTION OF TECHNOLOGY CORPORATION NAMING PRACTICES A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI'I IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN LINGUISTICS MAY 2005 By Barry Cowan Dissertation Committee: Michael Forman, Chairperson William 0'Grady Kenneth Rehg Andrew Wong Geoffrey White ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS As I have approached this stage, the end of my academic career as a student, I've been washed over by waves of sentimentality and surprising floods ofemotion. I never could have navigated to this point on my own, and the acknowledgements that follow cannot begin to express or repay my gratitude. I'll start with the professors that helped put me on the right track and guide me to this place. Joe Axelrod and Tom Scovel at San Francisco State University reached out to me when I was a shy underachieving student. At the University of Hawai'i, Byron Bender, Robert Blust, and Patricia Donegan were the fIrst ones to set me on the right path in Linguistics. Ann Peters took me under her wing for most ofmy time at UH, and I wouldn't have made it this far without her kind support and friendship. The members of my dissertation committee have all provided support and leadership in unique ways. Ken Rehg was my fIrst phonology professor at UH, he was on my comps committee, and he came in late, but with characteristic enthusiasm and interest to be on my dissertation committee. -

LINGUISTIC CONTRIBUTIONS to the SUCCESS of SILICON VALLEY's HI-TECH GLOBAL BRANDS by Chuansheng He

LINGUISTIC CONTRIBUTIONS TO THE SUCCESS OF SILICON VALLEY'S HI-TECH GLOBAL BRANDS by Chuansheng He Brand naming is an important domain of language use in modern commercial society and a field of potential pragmatic interest and investigation. Brand naming is a one-way communicative activity in which brand names are created to communicate the right information to the right people in a right manner. This article argues that linguistic characteristics of brand names can help contribute to brand success in two aspects: semantic appositeness and multilingual communi- cation. The article chooses Silicon Valley as a case study to demonstrate how the linguistic characteristics of hi-tech global brand names ensure an effective and relevant communication to consumers on a global basis. 1. The linguistic power of international brand names What's in a name? When it comes to a brand, it means enormous value. In an age of global economy, building global brand names is the ultimate goal for companies all over the world. Global brand names are the most valuable assets to their owners and are known all over the world, such as Coca-Cola, Ford, Goodyear, Ivory, Levi's, Maxwell House, etc. The success of these global brand names is in part due to the result of a long history of advertising and promotion. It took these brand names a hundred years or so, and several generations, to become household words. Most of them are just surnames of founders, such as Colgate, Cadbury, Heinz, Kellogg's, etc. By brand name criteria1, they are not 'good' names because they lack the distinctiveness of trademarks, and hence they may not be registered as such today. -

Brand, Company

Always, 213 Armourcote, 488 Amazon.com, 18, 21, 38,120, 206, 232, Armstrong, Lance, 217 Brand, Company 270, 299, 318, 319, 336, 344, 347, Arndt, Michael, 289 382, 408,442,481,482,490,493, Arquette, Courtney Cox, 156 Note: Italicized page numbers indicate 495,497,501-02,504,505 ASDA, 566 illustrations. AMD, 209,521 Ashkenazy, Vladirnir, 295 America Online (AOL), 38, 345,497,504-05 Asphalt Innovations, 311 !7 America West, 303 Associated Grocers, 373 A&P, 188, 353 American Airlines, 303, 385, 531, 581 Associates Sales Satisfaction Index AARP,488 American Association of Advertising Study, 214 Abbott Laboratories, 385 Agencies, 577 Association of Black Cardiologists, 132 ABC, 400 American Botanical Council, 365 Association of National Advertisers ABC World News Tonight, 436 American Customer Satisfaction Index, 227 (ANA), 438,439 Abercrombie & Fitch, 157, 361 American Demographics, 102 AT&T, 57,507, 508,580 Absolut Vodka, 429,492 American Eagle Outfitters, 121 ATA, 303 Academy Awards, 414 American Egg Board, 189 The Athelete's Foot, 367 Accenture, 222,247,410 American Express, 91, 119-20,188, 192, Auchan hypermaket, 561 Ace Hardware, 373 222,268,437,455'470-71,507,524 Audemars Piguet, 525 Achilles Track Club, 77 American Express Centurion card, 525-26 Audi, 93, 547 ACNielsen Corporation, 102, 117 American Girl Inc., 202, 219 Aussie shampoo, 198 ACNielsen's Scantrack, 261 American Greetings, 197 Automatic 5-Minute Pasta and Sausage Acoustimass system, 538 American Heritage Dictionary, 405 Maker, 489 ActiveGroup, 207 American Idol, 414, 430,