Japan April 2021 a Pril 2021

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Japan 500 2010 A-Z

FT Japan 500 2010 A-Z Japan rank Company 2010 77 Bank 305 Abc-Mart 280 Accordia Golf 487 Acom 260 Adeka 496 Advantest 156 Aeon 85 Aeon Credit Service 340 Aeon Mall 192 Air Water 301 Aisin Seiki 89 Ajinomoto 113 Alfresa Holdings 300 All Nippon Airways 109 Alps Electric 433 Amada 213 Aoyama Trading 470 Aozora Bank 293 Asahi Breweries 86 Asahi Glass 55 Asahi Kasei 104 Asics 330 Astellas Pharma 40 Autobacs Seven 451 Awa Bank 413 Bank of Iwate 472 Bank of Kyoto 208 Bank of Yokohama 123 Benesse Holdings 170 Bridgestone 52 Brother Industries 212 Canon 6 Canon Marketing Japan 320 Capcom 428 Casio Computer 310 Central Glass 484 Central Japan Railway 42 Century Tokyo Leasing 397 Chiba Bank 144 Chiyoda 264 Chubu Electric Power 35 Chugai Pharmaceuticals 71 Chugoku Bank 224 Chugoku Electric Power 107 Chuo Mitsui Trust 130 Circle K Sunkus 482 Citizen Holding 283 Coca-Cola West 345 Comsys Holdings 408 Cosmo Oil 323 Credit Saison 247 Dai Nippon Printing 81 Daicel Chemical Industries 271 Daido Steel 341 Daihatsu Motor 185 Daiichi Sankyo 56 Daikin Industries 59 Dainippon Screen Mnfg. 453 Dainippon Sumitomo Pharma 201 Daio Paper 485 Japan rank Company 2010 Daishi Bank 426 Daito Trust Construction 137 Daiwa House Industry 117 Daiwa Securities Group 84 Dena 204 Denki Kagaku Kogyo 307 Denso 22 Dentsu 108 Dic 360 Disco 315 Don Quijote 348 Dowa 339 Duskin 448 Eaccess 486 East Japan Railway 18 Ebara 309 Edion 476 Eisai 70 Electric Power Development 140 Elpida Memory 189 Exedy 454 Ezaki Glico 364 Familymart 226 Fancl 439 Fanuc 23 Fast Retailing 37 FCC 493 FP 500 Fuji Electric 326 Fuji Heavy Industries 186 Fuji Media 207 Fuji Oil 437 Fujifilm 38 Fujikura 317 Fujitsu 54 Fukuoka Financial 199 Fukuyama Transp. -

The Convocation Notice for the 83Rd FY Ordinary General Meeting of Shareholders

【TRANSLATION】 Aozora Bank, Ltd. Securities Code 8304 The Convocation Notice for the 83rd FY Ordinary General Meeting of Shareholders Contents ◆Notice on Exercise of Voting Rights 1 ◆The Convocation Notice for the 83rd FY Date & Time Ordinary General Meeting of Shareholders 3 June 28, 2016(Tuesday) ◆Reference Material for The General 10:00a.m. (Open 9:00 a.m.) Meeting of Shareholders 6 ◆Attached Documents of The Convocation Notice 21 Venue nd Business Report 21 Diamond Room on the 2 Floor of Hotel Grand Palace The Consolidated Financial Statements 52 1-1, Iidabashi 1-chome, Chiyodaku, Tokyo The Non-consolidated Financial Statements 55 (Please refer to map on the last page) Audit Reports 58 Proposals for Resolution: Proposal No.1 Amendments to the Articles of Incorporation Proposal No.2 Appointment of Eight Directors Proposal No.3 Appointment of One Audit & Supervisory Board Member Proposal No.4 Appointment of Two Alternate Audit & Supervisory Board Members A Retail Showroom showcasing the Bank’s retail banking business will be set up. Drinks and snacks will be available so please feel free to visit. 【Opening Times】 9:00 a.m. – 10:00 a.m. and for one hour from the closing of the Meeting of Shareholders Notice on Exercise of Voting Rights The following 3 methods may be used to exercise your voting rights. Attend the Shareholder’s Meeting Please present the “Exercise of Voting Rights Form” at the reception desk. Date & Time: June 28, 2016 (Tuesday) 10:00 a.m. (reception opens at 9:00 a.m.) Place: Diamond Room on the 2nd Floor of Hotel Grand Palace 1-1 Iidabashi 1-Chome, Chiyoda-Ku, Tokyo (Please refer to map on the last page) Exercise Your Voting Right in Writing Please write your vote of approval or disapproval on the enclosed “Exercise of Voting Rights Form” and return the form to us by mail. -

Benjamin Bystrom CV

Benjamin Bystrom 5426 Kirkwood Place, Honolulu, HI 96821, Cell: 808-226-6049, E-mail: [email protected] PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE 2004-Present University of Hawaii at Manoa, Instructor, Shidler College of Business Develop curriculum and teach graduate and undergraduate courses in banking, equity valuation, venture finance and global capital markets. Asian Field Study Program Director: design curriculum, teach course and lead students on a 3 week business tour visiting 25+ companies and institutions throughout Asia each year. Taught Executive Education courses in mergers and acquisitions and Asian financial markets. Sixteen time Professor of the Semester, Teaching Excellence Awards in 2011 and 2015. 2000-2003 Morgan Stanley, Tokyo, Executive Director Headed Asian Capital Markets team – generated annual profits of up to $35 million per year. Developed and executed solutions for restructuring major Japanese banks, finance companies and insurance companies – JPY300 billion+ in transactions completed. Advised on corporate acquisitions such as Prudential’s takeover of Kyoei Life. Structured and marketed major financings for global high yield and investment grade bonds, US and European leveraged loans, real estate loans, distressed debt and other assets. 1998-2000 Merrill Lynch, Tokyo, Vice-President Raised capital for major Japanese corporations such as Honda Finance and Aozora Bank. Managed Japan team responsible for structuring and closing asset-backed debt financings. Provided valuations, structuring and advisory to successfully execute Renault’s acquisition of Nissan Motors, AXA’s acquisition of Nichidan, and GM’s divestiture of Isuzu. 1996-1998 Moody's Investors Service, New York, Senior Analyst Lectured at global conferences in Asian, Europe and the U.S. and published leading research on Japanese financial markets, consumer credit, securitization structures and real estate markets. -

Investor Presentation -Appendix- (Ended Jun. 2017)

nd Period Fiscal Period22 ended June 30, 2017 * Fractions of the stated amounts are cut off and those of the ratios and years are rounded off unless otherwise indicated. Therefore, the aggregation of the figures Index stated hereupon are not necessarily identical to the total. 1. FINANCIAL HIGHLIGHTS • Overview of financial results • Portfolio overview - Office in Osaka area 2 34 for the fiscal period ended June 30, 2017 (22nd Period) 4 • Portfolio overview - Office in Osaka area 3 35 • 22nd Period financial results – Comparison to previous period 5 • Portfolio overview – TK interest and others 36 • 22nd Period financial results – Comparison to initial forecasts 6 • Newly acquired assets 37 • 22nd Period financial results – • Disposed assets 41 Breakdown of change from previous period 7 • Balance sheet 8 5. FINANCING STRATEGY • Income statement 9 • Major financing- related figures and investment corporation bonds 43 2. FORECASTS FOR THE 23RD AND 24TH FISCAL PERIOD • Financial status 44 • Forecasts for the 23rd and 24th fiscal period 11 • Lender composition and maturity ladder (as of end of Jun. 2017) 45 • Breakdown of change from previous period 12 • Outstanding borrowings (as of end of Jun. 2017) 46 3. RESULTS FOR THE 22ND FISCAL PERIOD • Lender composition and maturity ladder (as of end of Jul. 2017) 47 • Occupancy 14 • Outstanding borrowings (as of end of Jul. 2017) 48 • Portfolio operation 15 6. MARKET ENVIRONMENT • Occupancy by property 16 • Office market data 1 (Tokyo 23 districts) 51 • Revisions and gaps in rents 17 • Office market data 2 (Tokyo 23 districts) 52 • Surveys on tenants’ satisfaction 18 • Office market data 3 (Osaka) 53 • Initiatives in Properties in Portfolio 19 • Office market data 4 (Osaka) 54 4. -

Merger of Aozora Bank and Shinsei Bank

Merger of Aozora Bank and Shinsei Bank Creation of a Japanese financial institution that meets the needs of its customers and is truly sought by society July 1, 2009 0 Agenda ▶ Rationale for the Merger …2 ▶ Vision for the Merger …3 ▶ Values of the Combined Bank …4 ▶ Areas of Focus 1. Domestic Corporate Finance …5 2. Individual Customers …6 3. Alliances with Regional Financial Institutions …7 ▶ Overview of the Merger …8, 9 ▶ Company Profiles (as of March 31, 2009) …10 ▶ Key Takeaways …11 1 Rationale for the Merger Background Increasing importance of attaining Need for a neutral financial sufficient scale and maintaining a institution, unaffiliated with any strong financial platform particular financial group Aozora Bank and Shinsei Bank – Merger of Equals Secure Utilize IT and Develop products organizational Expand client base improve operational and services line-up stability efficiencies Enhance profitability 2 Vision for the Merger Deeply-rooted domestically, truly sought by customers, the market and society, and continually contributing to the development of the domestic economy and society Management and employees to foster a corporate culture that maximizes the Combined Bank’s capabilities Strive to further reinforce corporate governance and compliance functions Utilize advanced information technology to appropriately respond to customer needs and promote growth 3 Values of the Combined Bank Organizational stability Ranked sixth domestically in terms of total assets, the Combined Bank will secure organizational stability through -

The Convocation Notice for the 88Th FY Ordinary General Meeting of Shareholders to Be Held on Thursday June 24, 2021

【TRANSLATION】 [NOTICE: This Notice of Convocation is a translation of the Japanese original for reference purposes only, and in the event of any discrepancy, the Japanese original shall prevail.] Aozora Bank, Ltd. Securities Code 8304 The Convocation Notice for the 88th FY Ordinary General Meeting of Shareholders Contents ■There will be no thank-you gift for attendees. ◆Message from the CEO 1 ■The General Meeting of Shareholders will be ◆Information regarding the General Meeting of livestreamed (with viewer participation) Shareholders 2 ◆Information regarding the General Meeting of Shareholders livestream 3 Date & Time ◆The Convocation Notice for the 88th FY June 24, 2021 (Thursday) Ordinary General Meeting of Shareholders 5 10:00 a.m. (recption opens at 9:00 a.m.) ◆Notice on Exercise of Voting Rights 7 ◆Reference Material for The General Meeting of Shareholders 9 Venue ◆Attached Documents of The Convocation Notice 29 Diamond Room on the 2nd Floor Business Report 29 Consolidated Financial Statements 63 of Hotel Grand Palace Non-Consolidated Financial Statements 66 1-1, Iidabashi 1-chome, Chiyodaku, Tokyo Audit Reports 69 (Please refer to map on the last page) ◆Reference Material 74 Proposals for Resolution: Proposal No.1 Appointment of Eight Directors Proposal No.2 Appointment of Two Alternate Audit & Supervisory Board Members Proposal No.3 Determination of the Outlines of the Equity Compensation Type Stock Options for Full-time Directors Note that the Board of Directors have resolved to pay Please read the “Information regarding the a year-end common share dividend of 34 yen per share General Meeting of Shareholders” and for the 88h FY (4th quarter). -

Aozora Bank & Sophia University to Launch Joint Research Project In

Aozora Bank, Ltd. Sophia University July 10, 2019 NEWS RELEASE Aozora Bank & Sophia University to Launch Joint Research Project in Field of “Financial Gerontology” Tokyo July 10, 2019 — Aozora Bank, Ltd. (President and CEO: Shinsuke Baba; Head Office: Tokyo) (“Aozora” or “the Bank”) and Sophia University (President: Yoshiaki Terumichi; Tokyo) today announced their intent to launch a joint research project with a focus on financial gerontology. Financial gerontology is a relatively new academic discipline that examines the economic challenges associated with aging and the post-retirement generation’s approach to asset management. Research findings are expected to provide additional insights into the state of financial services in Japan, one of the world’s most rapidly aging countries. This joint research project is a result of discussions and complementary interests between Aozora, which has had a long-standing focus on asset management consulting for senior customers and recognizes the challenges posed by an aging society, and the Department of Psychology, Faculty of Human Sciences of Sophia University, which is pursuing a deeper understanding of geriatric psychology from the perspective of clinical psychology. The results of this research are expected to assist Aozora in further improving the quality of its retail banking services directed towards its mass-affluent senior generation customers as part of Aozora’s customer-oriented business management strategy. The research is expected to enable Sophia to lay the groundwork for a research program examining safer and happier retirement lifestyles for the senior generation by studying how the Bank responds to its senior customers. [Joint Research Summary] ■Research Subject A study into the effectiveness of financial services offered to seniors from the perspective of financial gerontology ■Research Overview 1. -

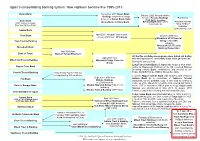

Japan's Consolidating Banking System: How Eighteen Became Six

Japan’s consolidating banking system: How eighteen became five 1995-2013 Daiwa Bank December 2001 Daiwa Bank October 2002. Merged entities Holdings results from merger become Resona Holdings Red border between of Daiwa Bank, Kinki Asahi Bank (TSE 8308) including Osaka Bank and Nara Bank. Resona Bank which does indicates current (1991 merger of Kyowa trust business entity. Red line Bank and Saitama Bank) indicates forthcoming event Sanwa Bank April 2001 ‘integrate’ businesses. Tokai Bank October 2005 form January 2002 form UFJ Group Mitsubishi UFJ Financial Group (TSE 8306) Toyo Trust & Banking including Mitsubishi UFJ Trust & Mitsubishi Bank Banking Corporation April 1996 form Bank of Tokyo Bank of Tokyo-Mitsubishi All the five surviving mega-groups were bailed out during April 2001 form this time by massive convertible loans .from government Mitsubishi Trust & Banking Mitsubishi Tokyo Financial During the same period: Group Long-Term Credit Bank of Japan was acquired from bank- Nippon Trust Bank ruptcy by Ripplewood Holdings of the US, renamed Shinsei [meaning reborn] Bank, rehabilitated, and relisted on the Yasuda Trust & Banking Tokyo Stock Exchange (TSE) in November 2004. Absorbed by Fuji in 1996 due to long-running NPL problems. Troubled Nippon Credit Bank was acquired and renamed September 2000 form Fuji Bank Aozora Bank by a consortium of Japanese financial Mizuho Holdings institutions led by Softbank Corp. It later sold its shares to In 2003 becomes Cerberus of the US which turned the bank around and listed it Dai-ichi Kangyo Bank Mizuho Financial Group (TSE 8411) on the TSE in November 2006.A plan to merge Aozora with including Shinsei was abandoned in May 2010. -

Portfolio of Investments

PORTFOLIO OF INVESTMENTS Variable Portfolio – Partners International Value Fund, September 30, 2020 (Unaudited) (Percentages represent value of investments compared to net assets) Investments in securities Common Stocks 97.9% Common Stocks (continued) Issuer Shares Value ($) Issuer Shares Value ($) Australia 4.2% UCB SA 3,232 367,070 AMP Ltd. 247,119 232,705 Total 13,350,657 Aurizon Holdings Ltd. 64,744 199,177 China 0.6% Australia & New Zealand Banking Group Ltd. 340,950 4,253,691 Baidu, Inc., ADR(a) 15,000 1,898,850 Bendigo & Adelaide Bank Ltd. 30,812 134,198 China Mobile Ltd. 658,000 4,223,890 BlueScope Steel Ltd. 132,090 1,217,053 Total 6,122,740 Boral Ltd. 177,752 587,387 Denmark 1.9% Challenger Ltd. 802,400 2,232,907 AP Moller - Maersk A/S, Class A 160 234,206 Cleanaway Waste Management Ltd. 273,032 412,273 AP Moller - Maersk A/S, Class B 3,945 6,236,577 Crown Resorts Ltd. 31,489 200,032 Carlsberg A/S, Class B 12,199 1,643,476 Fortescue Metals Group Ltd. 194,057 2,279,787 Danske Bank A/S(a) 35,892 485,479 Harvey Norman Holdings Ltd. 144,797 471,278 Demant A/S(a) 8,210 257,475 Incitec Pivot Ltd. 377,247 552,746 Drilling Co. of 1972 A/S (The)(a) 40,700 879,052 LendLease Group 485,961 3,882,083 DSV PANALPINA A/S 15,851 2,571,083 Macquarie Group Ltd. 65,800 5,703,825 Genmab A/S(a) 1,071 388,672 National Australia Bank Ltd. -

Infrastructure Investor Global Summit Investor Attendees Include

Infrastructure Investor Global Summit investor attendees include: ABL Life Insurance Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank Abu Dhabi Investment Council Asset Management One Co. Abu Dhabi Retirement Pensions and AustralianSuper Benefits Fund AXA Life Insurance Achmea BV Bank of Yokohama Aflac Life Insurance Japan Bankia AIMCo - Alberta Investment BCI Management Corp Benesse Group Pension Fund AISIN Employees' Pension Fund Border to Coast Pensions Partnership Albourne America Callan Alte Leipziger Lebensversicherung Cassa Depositi e Prestiti Aozora Bank Cathay Life Insurance AP4 CBUS Super Arzteversorgung Westfalen-Lippe CDC Group Asian Development Bank To join the community, visit the Global Summit website or contact a member of the team. China Life Gatewood Capital Partners City of Fresno Retirement Systems GIC Commonwealth Superannuation Government Pension Investment Fund Corporation Greater Manchester Pension Fund CPPIB HESTA Daido Life Insurance HQ Trust Daiwa House Industry Pension Fund HRM Pension Plan DBJ Asset Management HVB Pension Dea Capital Alternative Funds Hyundai Insurance DENSO Pension Fund Idemitsu Pension Fund derigo IMAS Foundation Desjardins Group Pension Plan IMCO DGB Life Insurance IST Investment Foundation Duskin Pension Fund Itochu Corp EBRD Japan Co-Op Insurance Consumers' Employees Provident Fund Board Co-Operative Federation First State Super Japan Investment Corporation Fondation Lucie Et André Chagnon Japan Post Bank Fubon Hyundai Life Insurance Co Japan Post Insurance Fujifilm Holdings To join the community, -

Nishimoto Co., Ltd

Note: This document has been translated from a part of the Japanese original for reference purposes only. In the event of any discrepancy between this translated document and the Japanese original, the original shall prevail. The Company assumes no responsibility for this translation or for direct, indirect or any other forms of damages arising from the translation. (Securities code 9260) March 11, 2020 To Shareholders with Voting Rights: Yoshiro Susaki Chairman Nishimoto Co., Ltd. (Head office) 3-2-1, Nihonbashi Muromachi, Chuo-ku, Tokyo, Japan (Registered main office) 4-1-38 Isobe-dori, Chuo-ku, Kobe-shi, Hyogo Prefecture, Japan NOTICE OF THE 73RD ANNUAL GENERAL MEETING OF SHAREHOLDERS We would like to express our appreciation for your continued support and patronage. You are cordially invited to attend the 73rd Annual General Meeting of Shareholders of Nishimoto Co., Ltd. (the “Company”). The meeting will be held for the purposes as described below. If you are unable to attend the meeting, you can exercise your voting rights in writing. Please review the attached Reference Documents for the General Meeting of Shareholders, indicate your vote for or against the proposals on the enclosed Voting Rights Exercise Form, and return it so that it is received by the Company by 6:00 p.m. Japan time on Wednesday, March 25, 2020. 1. Date and Time: Thursday, March 26, 2020 at 10:00 a.m. Japan time (Reception will open at 9:00 a.m.) 2. Place: Hall at Muromachi Mitsui Hall & Conference on the third floor of Nihonbashi Muromachi Mitsui Tower located at 3-2-1, Nihonbashi Muromachi, Chuo-ku, Tokyo, Japan *Please be noted that the venue has been changed from the previous Annual General Meeting of Shareholders. -

Japan 500 2008 A-Z

FTJapan 500 2008 A-Z Japan rank Company 2008 Abc-Mart 349 Access 451 Acom 199 Advantest 167 Aeon 87 Aeon Credit Service 333 Aeon Mall 172 Aiful 282 Aioi Insurance 202 Air Water 377 Aisin Seiki 76 Ajinomoto 122 Alfresa 246 All Nippon Airways 99 Alps Electric 373 Amada 260 Aoyama Trading 430 Aozora Bank 177 Aruze 296 Asahi Breweries 85 Asahi Glass 57 Asahi Kasei 116 Asatsu-DK 404 Asics 309 Astellas Pharma 36 Awa Bank 459 Bank of Iwate 480 Bank of Kyoto 196 Bank of Nagoya 474 Bank of Yokohama 88 Benesse 175 Bosch 363 Bridgestone 54 Brother Industries 273 Canon 6 Canon Sales 274 Capcom 315 Casio Computer 209 Central Japan Railway 31 Chiba Bank 138 Chiyoda 381 Chubu Electric Power 39 Chugai Pharmaceuticals 132 Chugoku Bank 243 Chugoku Electric Power 104 Circle K Sunkus 432 Citizen Watch 253 Coca-Cola West Japan 285 Comsys 478 Cosmo Oil 287 Credit Saison 170 CSK 364 Dai Nippon Printing 73 Daicel Chemical Industries 358 Daido Steel 319 Daifuku 436 Daihatsu Motor 169 Daiichi Chuo Kisen 357 Daiichi Sankyo 34 Daikin Industries 60 Dainippon Sumitomo Pharma 225 Daiseki 458 Daishi Bank 442 Daito Trust Construction 125 Daiwa House Industry 143 Daiwa Securities Group 65 Davinci Advisors 495 Dena 259 Denki Kagaku Kogyo 415 Denso 24 Dentsu 130 Diamond Lease 276 DIC 297 Disco 433 Don Quijote 469 Dowa Mining 367 East Japan Railway 20 Ebara 473 Eisai 83 Electric Power Development 139 Elpida Memory 197 Exedy 453 Ezaki Glico 371 Familymart 231 Fanuc 32 Fast Retailing 89 Fuji Electric 261 Fuji Fire & Marine Insurance 479 Fuji Heavy Industries 247 Fuji Photo