Stihl Incorporated: Go-To-Market Strategy for Next-Generation Consumers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Press Release (PDF)

Press release Stockholm April 16, 2020 Invitation to presentation of Husqvarna Group´s Interim Report, Q1 2020 Husqvarna Group's interim report, Q1 2020 will be published on Friday April 24 at 08:00 CET. Husqvarna Group will hold a presentation of the report on the same day and invites investors, analysts and media to a conference call and webcast at 10:00 CET where Henric Andersson President and CEO, and Glen Instone, CFO will comment on the Q1 result. The presentation will be held in English and followed by a Q&A session. The report and conference call slides will be available at: https://www.husqvarnagroup.com/en/investors Information to participants: To participate in the teleconference, please use the following dial-in details below: • SE: +46 8 505 583 55 • UK: +44 333 300 9273 • US: +1 833 526 8347 The telephone conference can be followed live on: https://husqvarna-group.creo.se/200424, and a recording will also be available afterwards. For more information, please contact: Jenny Huselius, Manager, Corporate Communications and Investor Relations + 72 855 16 80 eller [email protected] Husqvarna Group Husqvarna Group is a global leading producer of outdoor power products and innovative solutions for forest, park and garden care. Products include chainsaws, trimmers, robotic lawn mowers and ride-on lawn mowers. The Group is also the European leader in garden watering products and a global leader in cutting equipment and diamond tools for the construction and stone industries. The Group’s products and solutions are sold under brands including Husqvarna, Gardena, McCulloch, Poulan Pro, Weed Eater, Flymo, Zenoah and Diamant Boart via dealers and retailers to consumers and professionals in more than 100 countries. -

CITY of JOPLIN SURPLUS ITEMS Auction – September 18, 2021

CITY OF JOPLIN SURPLUS ITEMS Auction – September 18, 2021 SURPLUS ITEMS: ITEM DESCRIPTION QUA DEPARTME Equipmen VIN # if ASSET NTITY NT t # Applicable TAG # office chairs green leather chairs 2 City Clerk with padded arms. office chair black leather, 1 City Clerk adjustable Desktop Dell Optiple 19WXPW1 9033- IT 4th x 3010 000073 St 3 Misc Box of IT 4th Network switches St Eq and hubs Desktop Dell Optiple 9VZ8DZ1 9033- IT 4th x 3010 000075 St 7 Desktop Dell Optiple 19YWPW1 9033- IT 4th x 3010 000073 St 2 Desktop Dell Optiple 3SWNSW1 9033- IT 4th x 3010 000074 St 4 Desktop Dell Optiple 9WB9DZ1 9033- IT 4th x 3010 000075 St 6 Desktop Dell Optiple FH7P8z1 9033- IT 4th x 3010 000075 St 2 Desktop Dell Optiple 6HJ2S22 9033- IT 4th x 3020 000129 St 0 Desktop Dell Optiple 3SVRSW1 9033- IT 4th x 3010 000074 St 5 Desktop Dell Optiple 19ZVPW1 9033- IT 4th x 3010 000073 St 0 Desktop Dell Optiple 6HKYR22 9033- IT 4th x 3020 000127 St 9 CITY OF JOPLIN SURPLUS ITEMS Desktop Dell Optiple 6HL5S22 9033- IT 4th x 3020 000128 St 9 Desktop Dell Optiple 6HK5S22 9033- IT 4th x 3020 000128 St 0 Desktop Dell Optiple 6HM6S22 9033- IT 4th x 3020 000128 St 1 Desktop Dell Optiple 19ZVPW1 9033- IT 4th x 3010 000073 St 0 Desktop Dell Optiple 3SVRSW1 9033- IT 4th x 3010 000074 St 5 Desktop Dell Optiple 6HJ2S22 9033- IT 4th x 3020 000129 St 0 Desktop Dell Optiple FH7Q8Z1 9033- IT 4th x 3010 000075 St 3 Desktop Dell Optiple 9WR7DZ1 9033- IT 4th x 3010 000075 St 5 Desktop Dell Optiple C5CD6Y1 9033- IT 4th x 3010 000074 St 0 Desktop Dell Optiple C5BD6Y1 9033- IT 4th x 3010 -

Clutch Assy & Drum & Housing

CLUTCH ASSY & DRUM & HOUSING TURFMASTER no. Image may not depict the Description Replaces Model. OEM no. actual size, shape, etc. ALPINA CASTOR ACLUSTIFS80 Models: Alpina Clutch Assy, 21, 22, 25, 26, 30, 31 Measures Hedgetrimmer TS27 MB280, Alpina ■ Dia . 51.5 mm Alpina MB28D, SB28, SB30, SH65 VIP 21 3660450 ■ Shoe Hight 16mm Castor VIP 25 VIP 30 STAR 22 STAR 26 STAR 31 ■ Hole 8mm A3660450 SB 28 ■ Hole Hight 7mm Castor TURBO 21 TURBO 25 TURBO 30 POWER 22 ACLUMITTL52/75 Models: Clutch Assy, Alpina Measures 34, 36, 40, 41, 45 VIP 34 ■ Dia.75mm Alpina VIP 40 VIP 42 STAR 36 STATR 41 STAR Alpina ■ Shoe Hight 14mm Castor 45 SB 39 SB 40 SB 44 3660430 ■ Hole 10mm, Castor ■ Hole Hight 8.5mm TURBO 34 TURBO 40 TURBO POWER 36 POWER 41 POWER 45 SB39 SB 40 SB 44 AAB18616 Clutch Bolt ■ for AAB31120 ■ 17 Wrench hexagon Alpina Models: Alpina ■ 10 Clutch hole height Castor Alpina 34, 36, 40, 41, 34 ■ 10 clutch hole Ø 2123100 ■ Thread Ø 8 ■ M 1,25 Thread pitch CRAFTSMAN AAST255-371 Models: Craftsman 358351181, 358351162, 358351143, 358351063, 358351082, 358351182, 358352660, 358352670, 358350240, 358351161, 358352181, 358352160, 358352162, 358352161, 358352180. 358351191, 358348221, 358350203, 358351141, 358351142, Clutch Assy, 358351042, 358351480, 358348231, 358348211, Measures 358350200, 358351041, 358351080, 358351060, Craftsman ■ Dia.??mm Craftsman 358351061, 358351062, 358351081, 358352730, 530 01 49 49 ■ Shoe Hight ??mm 358352800, 35832830. 358360100, 358360150, 530 09 41 88 ■ Hole ?mm 358350570, 358350560, 358351140, 35835108, ■ Hole Hight ?? mm -

HAWTHORNE, CA ONSITE Commercial & Landscape Equipment Auction 5/9/17 ID:4487

09/26/21 12:19:24 HAWTHORNE, CA ONSITE Commercial & Landscape Equipment Auction 5/9/17 ID:4487 Auction Opens: Tue, Apr 18 3:16pm MT Auction Closes: Tue, May 9 12:00pm MT Lot Title Lot Title 6001 Utility GVW2900 Pull Trailer With Hitch, 123" 6019 Craftsman 917.377543Mulcher With 6.5 HP, X 60" X 48"H 22" Blade, & Power Gear Drive 6001A Utility GVW2900 Pull Trailer With Hitch, 123" 6020 Gas-Powered Lawnmower X 60" X 48"H 6021 Sears 917.270260 Lawnmower With 6 HP & 6002 Utility Trailer With Hitch, 86" x 49" x 24"H 2222CC Engine 6003 International Harvester Riding Lawnmower 6023 Karcher 2500 PSI, 2.4 GPM Power Washer Utility Trailer, 43" x 29" x 22"H 6025 MTD 11A-084E729 "Yard Machines" 4.5 HP 6004 Genie Superlift Contractor SLC-18 Load & 22" Blade Lawn Mower Transport, 18' Lift Height, 650 LB Load 6026 Black Max GCV 160 Over Head Cam 2600 Capacity PSI, 2.3 GPM Pressure Washer 6005 Campbell Hausfeld VT627505AJ 5-HP, 80- 6027 Excell VR2500 Residential 2500 PSI, 6.5 HP Gallon, 4-Cylinder Dual-Voltage Single Stage Quantum Pressure Washer Air Compressor 6028 Montgomery Ward GIL 1580 J Rototiller 6006 Husky Pro VT631403AJ(AGM03) 60-Gallon 3.2 HP Electric Air Compressor 6029 Mobile Box-Style Wet/Dry Vacuum 6007 Wacker Gas-Powered Dirt Compactor 6030 Troy Built Pressure Washer With Briggs & Stratton "675 Series" 190cc, 6.75 Ft-Lbs Gross 6008 Metal Winding Machine With Baldor Motor, Torque Engine 78" x 53" x 23"H 6031 True Temper "Steel Handles" Wheelbarrow 6009 Jet Hydraulic Press, 53" x 24" x 20"H 6032 Metal Push & Pull Lawn Roller 6010 Handy Industries, LLC. -

Press Release Stockholm March 5, 2020

Press release Stockholm March 5, 2020 Estimation of the Covid-19 impact on Husqvarna Group’s net sales for the first quarter 2020 Husqvarna Group estimates that the impact on net sales for the first quarter 2020 will be approximately 3 percent (with Q1 2019 as the reference*) due to supply chain disturbances related to the COVID-19 virus outbreak. The COVID-19 virus outbreak development has high attention within the Husqvarna Group and the company is doing the utmost to secure the health and safety of our employees and minimize any impact on the operations. All of the Group’s three production units in China have been up and running since mid-February, and are gradually increasing the capacity. Initiatives taken to minimize the impact on the business include securing components and transportation, as well as utilizing alternative suppliers. Given the dynamics related to the regions affected, where the situation in China is stabilizing and gradually improving whilst in Europe still somewhat uncertain, it is currently difficult to provide visibility of how long the supply chain impact might remain. However, from what we can see at this stage, there is no impact on customer demand as a consequence of COVID-19. *Adjusted for exits of the Consumer Brands business For additional information, please contact Johan Andersson, Director, Corporate Communications and Investor Relations +46 702 100 451 or [email protected] Husqvarna Group Husqvarna Group is a global leading producer of outdoor power products and innovative solutions for forest, park and garden care. Products include chainsaws, trimmers, robotic lawn mowers and ride-on lawn mowers. -

Press Release (PDF)

Press release Stockholm June 30, 2021 Conversion of shares According to Husqvarna AB´s articles of association, owners of Class A shares have the right to have such shares converted to Class B shares. Conversion reduces the total number of votes in Husqvarna AB. When such a conversion has occurred, the company is obligated by the Act on Trading in Financial Instruments to disclose any such change. In May 2021, at the request of shareholders, 56 Class A shares were converted to Class B shares. The total number of votes thereafter amounts to 157,919,825.3. The total number of registered shares in the company amounts to 576,343,778 shares of which 111,428,275 are Class A shares and 464,915,503 are Class B shares. This information is such that Husqvarna AB must disclose in accordance with the Financial Instruments Trading Act. The information was submitted for publication on June 30, 2021, at 18:00 CET. For additional information, please contact Johan Andersson, Vice President, Investor Relations [email protected]; +46 702 100 451 Husqvarna Group Husqvarna Group is a global leading producer of outdoor power products and innovative solutions for forest, park and garden care. Products include chainsaws, trimmers, robotic lawn mowers and ride-on lawn mowers. The Group is also the European leader in garden watering products and a global leader in cutting equipment and diamond tools for the construction and stone industries. The Group’s products and solutions are sold under brands including Husqvarna, Gardena, McCulloch, Poulan Pro, Weed Eater, Flymo, Zenoah and Diamant Boart via dealers and retailers to consumers and professionals in more than 100 countries. -

Press Release Stockholm, March 30, 2021

Press release Stockholm, March 30, 2021 Invitation to presentation of Husqvarna Group's first quarter 2021 Husqvarna Group invites you to a presentation of the quarterly report on April 22, 2021 at 10.00 a.m. CET. The briefing will take place by conference call that will also be webcast on Husqvarna Group’s website. The report is scheduled for publication at 07.30 a.m. CET on the same date. The interim report for the first quarter of 2021 will be presenteD by Husqvarna Group’s PresiDent & CEO Henric Andersson and CFO Glen Instone. The briefing will be helD in English and followed by a Q&A session. Dial-in numbers for the conference call: SE: +46 8 505 583 73 UK: +44 333 300 9263 US: +1 833 526 8398 Link to webcast: https://husqvarna-group.creo.se/210422 For more information please contact: Johan Andersson, Director, Corporate Communications and Investor Relations, +46 702 100 451 or [email protected] Husqvarna Group Husqvarna Group is a global leading producer of outdoor power products and innovative solutions for forest, park and garden care. Products include chainsaws, trimmers, robotic lawn mowers and ride-on lawn mowers. The Group is also the European leader in garden watering products and a global leader in cutting equipment and diamond tools for the construction and stone industries. The Group’s products and solutions are sold under brands including Husqvarna, Gardena, McCulloch, Poulan Pro, Weed Eater, Flymo, Zenoah and Diamant Boart via dealers and retailers to consumers and professionals in more than 100 countries. Net sales in 2020 amounted to SEK 42bn and the Group has around 12,400 employees in 40 countries. -

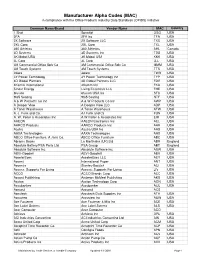

MAC List for Website.Xlsx

Manufacturer Alpha Codes (MAC) in compliance with the Office Products Industry Data Standards (OPIDS) Initiative Common Name/Brand Vendor Name MAC Country 1 Shot Spraylat OSG USA 2FA 2FA Inc TFA USA 2X Software 2X Software LLC TXS USA 2XL Corp. 2XL Corp TXL USA 360 Athletics 360 Athletics AHL Canada 3D Systems 3D Systems Inc TDS USA 3K Mobel USA 3K Mobel USA KKK USA 3L Corp 3L Corp LLL USA 3M Commercial Office Sply Co 3M Commercial Office Sply Co MMM USA 3M Touch Systems 3M Touch Systems TTS USA 3ware 3ware TWR USA 3Y Power Technology 3Y Power Technology Inc TYP USA 4D Global Partners 4D Global Partners LLC FDG USA 4Kamm International 4Kamm Intl FKA USA 5-hour Energy Living Essentials LLC FHE USA 6fusion 6fusion USA Inc SFU USA 9to5 Seating 9to5 Seating NTF USA A & W Products Co Inc A & W Products Co Inc AWP USA A Deeper View A Deeper View LLC ADP USA A Toner Warehouse A Toner Warehouse ATW USA A. J. Funk and Co. AJ Funk and Co FUN USA A. W. Peller & Associates Inc A W Peller & Associates Inc EIM USA AAEON AAEON Electronics Inc AEL USA AARCO Products AARCO Products Inc AAR USA Aastra Aastra USA Inc AAS USA AAXA Technologies AAXA Technologies AAX USA ABCO Office Furniture, A Jami Co. ABCO Office Furniture ABC USA Abrams Books La Martinière (UK) Ltd ABR England Absolute Battery/PSA Parts Ltd. PSA Group ABT England Absolute Software Inc. Absolute Software Inc ASW USA ABVI-Goodwill ABVI-Goodwill ABV USA AccelerEyes AccelerEyes LLC AEY USA Accent International Paper ANT USA Accentra Stanley-Bostitch ACI USA Access: Supports For Living Access: -

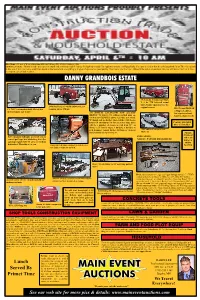

Main Event Auctions

Directions: 3.2 miles West of Fosston MN on US hwy #2. 39110, 310th ave SE. Auctioneer’s note : Danny’s trade was concrete work and setting up mobile homes. In looking through his equipment, tools, and household, it becomes evident that he only bought the best. There is no junk on this sale. From the heavy equipment down to the household, everything is in great shape and of good quality, most items are like new. Although the sale is an outdoor sale, we will move much of it into the shop in case of bad weather. DANNY GRANDBOIS ESTATE ‘76 Lincoln Continental Mark V 2 dr, 77K believed actual miles. Danny’s parents were the 1946 Studebaker 3 ton M-1628 truck, not original owners. 4 ½’ X 13’ custom shop built all steel box running, shows 49K mi. PROTO and HOMAK enclosed single axle trailer. rolling tool cabinet, 331 BOBCAT EXCAVATOR AND ATTACH- lots of powered and MENTS: ‘98 Bobcat 331 rubber-tracked mini ex- hand mechanic’s tools cavator ser# 512915223 shows 3,233 hrs, not actual. W/thumb and one bucket, there will be a 360 degree hydra tilt attachment for the excavator arm, there Century 250 MIG will be a number of augers as well from 24” on wire feed welder down, a 24” barrel auger, 4 buckets, a breaker or jack hammer, cement bucket, ditching or cleanout ‘98 Cadillac Concourse 4dr, bucket, blade for excavator, etc. 152K mi. Subsite FIREARMS C200 soil Self-contained hydraulic powered remote saber air control pull type box blade/drag box. -

Husqvarna Annual Report 2015

Annual Report 2015 R e s p e c t i n g n a t u r e – c a r i n g f o r p e o p l e The year and operations Board of Directors’ Report Financial statements Other information Husqvarna Group in brief A global leading producer of outdoor power products Husqvarna Group is a global leading producer of outdoor power products for forest, park and garden care. Products include chainsaws, trimmers, robotic lawn mowers and ride-on lawn mowers. The Group is also the European leader in garden watering products and a global leader in cutting equipment and diamond tools for the construction and stone industries. The Group’s products and solutions are sold under brands including Husqvarna, Gardena, McCulloch, Poulan Pro, Weed Eater, Flymo, Zenoah and Diamant Boart via dealers and retailers to consumers and professionals in more than 100 countries. Net sales in 2015 amounted to SEK 36bn and the Group has more than 13,000 employees in 40 countries. Divisions Husqvarna Gardena A global leader with a broad and innovative Share of Group A European leader in garden watering and Share of Group range of premium outdoor products such as net sales hand tools. The leadership position is built net sales chainsaws, trimmers and mowers for forest, park on offering innovative products based on and garden care. Products are sold to profession- consumer insight driven design and a strong als and demanding consumers through servicing 49% brand recognition among the passionate 13% dealers in more than 100 countries. Brands gardeners. -

Press Release November 24, 2020

Press release November 24, 2020 Husqvarna Group is further expanding its offering in surface preparation through the acquisition of Blastrac Husqvarna Group’s Construction Division has signed an agreement to acquire Blastrac, a leading provider of surface preparation technologies for the global construction and remediation industry. “The acquisition of Blastrac strengthens and complements our organic growth ambitions, as we are further expanding into complementary surface preparation solutions. This will enable us to provide customers with a complete range of solutions for any given surface preparation task,” said Henric Andersson, President & CEO, Husqvarna Group. The Blastrac product portfolio includes high-quality and efficient solutions for shot blasting, scarifying, scraping, grinding & polishing and dust collection. Blastrac’s net sales during last 12 months amounted to approximately SEK 600m. The company has 380 employees globally with manufacturing and sales offices in North America, Europe and Asia with sales in more than 80 countries. “The acquisition aims to further build and expand our offering in the market for surface preparation. Blastrac's business fits well into our growth strategy and will enable us to expand to our existing and new customers,” said Karin Falk, President, Construction Division. “In addition, the Blastrac team will bring extensive product and market expertise with these complementary solutions.” The parties aim at closing the acquisition by the end of 2020. The acquisition is subject to approval by relevant competition authorities. For further information, please contact: Johan Andersson, Director, Group Corporate Communications and Investor Relations, [email protected] +46 702 100 451 Husqvarna Group Husqvarna Group is a global leading producer of outdoor power products and innovative solutions for forest, park and garden care. -

Press Release Stockholm August 31, 2021

Press release Stockholm August 31, 2021 Conversion of shares According to Husqvarna AB´s articles of association, owners of Class A shares have the right to have such shares converted to Class B shares. Conversion reduces the total number of votes in Husqvarna AB. When such a conversion has occurred, the company is obligated by the Act on Trading in Financial Instruments to disclose any such change. In July 2021, at the request of shareholders, 400 Class A shares were converted to Class B shares. The total number of votes thereafter amounts to 157,919,462.6. The total number of registered shares in the company amounts to 576,343,778 shares of which 111,427,872 are Class A shares and 464,915,906 are Class B shares. This information is such that Husqvarna AB must disclose in accordance with the Financial Instruments Trading Act. The information was submitted for publication on August 31, 2021, at 16:00 CET. For additional information, please contact Johan Andersson, Vice President, Investor Relations [email protected]; +46 702 100 451 Husqvarna Group Husqvarna Group is a global leading producer of outdoor power products and innovative solutions for forest, park and garden care. Products include chainsaws, trimmers, robotic lawn mowers and ride-on lawn mowers. The Group is also the European leader in garden watering products and a global leader in cutting equipment and diamond tools for the construction and stone industries. The Group’s products and solutions are sold under brands including Husqvarna, Gardena, McCulloch, Poulan Pro, Weed Eater, Flymo, Zenoah and Diamant Boart via dealers and retailers to consumers and professionals in more than 100 countries.