Diplomarbeit

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Humanitarian Needs of Sahrawi Refugees in Algeria 2016 – 2017

Humanitarian Needs of Sahrawi Refugees in Algeria 2016 – 2017 1 July 2016 Caption cover page: A Sahrawi refugee, here with her children, lost her house due to the heavy rains in October 2015 and now is living in a tent, in Awserd camp, in Tindouf, Algeria. UNHCR/M.Redondo 2 Overview Financial Requirements 2016: USD 60,698,012 2017: USD 74,701,684 3 Executive Summary The Sahrawi refugee situation is one of the most protracted refugee situations in the world. Refugees from Western Sahara have been living in camps near Tindouf in southwest Algeria since 1975. The Government of Algeria recognized them as prima facie refugees, and has been hosting them in five camps, enabling access to public services, and providing infrastructure such as roads and electricity. In 1986, the host government requested the United Nations to assist Sahrawi refugees until a durable solution was found. Humanitarian assistance provided by UN agencies, international and national NGOs is based on a population planning figure of 90,000 vulnerable Sahrawi refugees. An additional 35,000 food rations are provided to persons with poor nutritional status. Pending a political solution, and due to the harsh conditions and remote location of the five refugee camps, the refugee population remains extremely vulnerable and entirely dependent on international assistance for their basic needs and survival. Due to the protracted situation of Sahrawi refugees and emergence of other large-scale humanitarian emergencies, funding levels have greatly decreased in recent years but humanitarian needs remain as pressing as ever. Lack of funding has severely affected the delivery of life-saving assistance to Sahrawi refugees by all organizations operating in the camps. -

Human Rights in Western Sahara and in the Tindouf Refugee Camps

Morocco/Western Sahara/Algeria HUMAN Human Rights in Western Sahara RIGHTS and in the Tindouf Refugee Camps WATCH Human Rights in Western Sahara and in the Tindouf Refugee Camps Morocco/Western Sahara/Algeria Copyright © 2008 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 1-56432-420-6 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch 350 Fifth Avenue, 34th floor New York, NY 10118-3299 USA Tel: +1 212 290 4700, Fax: +1 212 736 1300 [email protected] Poststraße 4-5 10178 Berlin, Germany Tel: +49 30 2593 06-10, Fax: +49 30 2593 0629 [email protected] Avenue des Gaulois, 7 1040 Brussels, Belgium Tel: + 32 (2) 732 2009, Fax: + 32 (2) 732 0471 [email protected] 64-66 Rue de Lausanne 1202 Geneva, Switzerland Tel: +41 22 738 0481, Fax: +41 22 738 1791 [email protected] 2-12 Pentonville Road, 2nd Floor London N1 9HF, UK Tel: +44 20 7713 1995, Fax: +44 20 7713 1800 [email protected] 27 Rue de Lisbonne 75008 Paris, France Tel: +33 (1)43 59 55 35, Fax: +33 (1) 43 59 55 22 [email protected] 1630 Connecticut Avenue, N.W., Suite 500 Washington, DC 20009 USA Tel: +1 202 612 4321, Fax: +1 202 612 4333 [email protected] Web Site Address: http://www.hrw.org December 2008 1-56432-420-6 Human Rights in Western Sahara and in the Tindouf Refugee Camps Map Of North Africa ....................................................................................................... 1 Summary...................................................................................................................... 2 Western Sahara ....................................................................................................... 3 Refugee Camps near Tindouf, Algeria ...................................................................... 8 Recommendations ...................................................................................................... 12 To the UN Security Council .................................................................................... -

Refugee Camps and Exile in the Construction of the Saharawi Nation

Singing like Wood-birds: Refugee Camps and Exile in the Construction of the Saharawi Nation Nicola Cozza Wolfson College Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Development Studies Refugee Studies Centre Queen Elizabeth House Faculty of Social Studies University of Oxford Trinity Term 2003 [ttf CONTENTS Acknowledgments viii Glossary of abbreviations and acronyms ix Maps x - xv I - INTRODUCTION 1 'Humanitarian emergencies': the merging of global influences and local processes 4 Saharawi refugees, Polisario camps and social change 7 Methodological considerations 12 Verbal interactions 15 Trust, tribes and bias: assessing interviewees' information 19 Fieldwork and trans-local processes 22 Outline of the following chapters 26 II - THE GENESIS OF WESTERN SAHARA AND OF ITS POST-COLONIAL CONFLICT. AN HISTORICAL ANALYSIS 31 Western Sahara: a geographical overview 32 The birth of the Moors 34 Traditional tribal hierarchies 37 Inter-tribal hierarchies 37 The 'tribe' in Western Sahara 41 The 'ghazi' and social change 43 Spanish colonisation 45 From Spanish colony to Spanish province 48 Identifying Spanish Saharawi and providing goods and services 55 Colonial plans for independence 61 The birth of the Polisario Front 63 The last years of Spanish colonisation in Western Sahara 64 Genesis and development of the armed conflict in Western Sahara 71 III - WHO ARE THE SAHARAWI? THE REGIONAL AND INTERNATIONAL DIMENSIONS OF THE PEACE-PROCESS IN WESTERN SAHARA 78 'Saharawi': blood, land and word-games 79 From the UN to the OAU, and back to the UN 82 The MINURSO and the 1991 UN plan 85 The dispute over voter eligibility 91 The 1974 Census 92 Morocco vs. -

Un Must Monitor Human Rights in Western Sahara and the Sahrawi Refugee Camps in Tindouf

www.amnesty.org AMNESTY INTERNATIONAL PUBLIC STATEMENT 22.10.2020 MDE 29/3235/2020 UN MUST MONITOR HUMAN RIGHTS IN WESTERN SAHARA AND THE SAHRAWI REFUGEE CAMPS IN TINDOUF Independent, impartial, comprehensive and sustained human rights monitoring must be a central element of the UN’s future presence in Western Sahara and Sahrawi refugee camps, Amnesty International said today, calling the UN Security Council to strengthen the UN Mission for the Referendum in Western Sahara (MINURSO) by adding a human rights component to its mandate. The UN Security Council is due to vote on the renewal of the mandate of MINURSO on 28 October three days ahead of its expiry. MINURSO is one of the only modern UN peacekeeping missions without a human rights mandate. Human rights violations and abuses have been committed by both sides - the Moroccan authorities and pro-independence movement the Polisario Front - in the more than 40-year dispute over the territory. On 14 September, in her global human rights update during the 45th session of the Human Rights Council, UN High Commissioner for Human Rights stated that the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights "continue remote monitoring of the situation in Western Sahara," where technical missions were last conducted five years ago. Lack of an independent mechanism to monitor human rights Restrictions on access for independent human rights organizations and journalists remained in place which have curtailed monitoring of human rights abuses in Western Sahara and the refugee camps in Tindouf in Algeria. Early this year on 25 and 28 February, the Moroccan authorities expelled at least nine people upon their arrival at Laayoune airport, including several Spanish parliamentarians and a Spanish lawyer, who had planned to observe the trial of a human rights activist (Khatri Dada, mentioned below). -

Page 1 FAO Emergency Centre for Locust Op Er a Tions

warning level: CAUTION D E S E R T L O C U S T B U L L E T I N FAO Emergency Centre for Locust Op er a tions No. 457 General Situation during October 2016 (3.11.2016) Forecast until mid-December 2016 As a result of summer breeding, two Desert new generation of adult groups and small swarms Locust outbreaks developed during October, is likely to form from about mid-November onwards one in western Mauritania and one in northern in western Mauritania and are likely to move into Sudan. In both countries, additional survey Western Sahara and northern Mauritania where good teams were immediately mobilized and control rains fell and further breeding could occur. Scattered operations were launched. It is likely that the adults were present along the southern side of the Mauritanian outbreak will extend into areas of Atlas Mountains in Morocco and in western Algeria. recent heavy rains in the north of the country as Control operations were undertaken along the Mali well as in Western Sahara where further breeding border in southern Algeria against high densities of is expected. A failure to control the outbreak hoppers. Locust numbers declined in the summer combined with unusually heavy and widespread breeding areas of northern Niger and Chad where rainfall might eventually lead to an upsurge in primarily low numbers of adults persisted. northwest Africa next spring but this is far from certain. In Sudan, adult groups and perhaps a few Central Region. An outbreak developed in small swarms are expected to form and move to North Kordofan and the Baiyuda Desert of northern winter breeding areas along the Red Sea coast, Sudan as a result of summer breeding and drying especially in northeast Sudan and southeast conditions. -

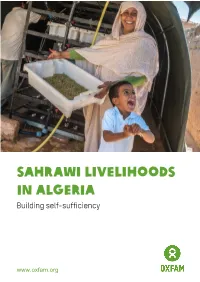

Sahrawi Livelihoods in Algeria: Building Self

Sahrawi livelihoods in algeria Building self-sufficiency www.oxfam.org OXFAM CASE STUDY – SEPTEMBER 2018 Over 40 years ago, Oxfam began working with Sahrawi refugees living in extremely harsh conditions in camps in the Saharan desert of western Algeria, who had fled their homes as a result of ongoing disputes over territory in Western Sahara. Since then, the Sahrawi refugees have been largely dependent on humanitarian aid from a number of agencies, but increasing needs and an uncertain funding future have meant that the agencies are having to adapt their programme approaches. Oxfam has met these new challenges by combining the existing aid with new resilience-building activities, supporting the community to lead self-sufficient and fulfilling lives in the arid desert environment. © Oxfam International September 2018 This case study was written by Mohamed Ouchene and Philippe Massebiau. Oxfam acknowledges the assistance of Meryem Benbrahim; the country programme and support teams; Eleanor Parker; Jude Powell; and Shekhar Anand in its production. It is part of a series of papers written to inform public debate on development and humanitarian policy issues. For further information on the issues raised in this paper please email Mohamed Ouchene ([email protected]) or Philippe Massebiau ([email protected]). This publication is copyright but the text may be used free of charge for the purposes of advocacy, campaigning, education, and research, provided that the source is acknowledged in full. The copyright holder requests that all such use be registered with them for impact assessment purposes. For copying in any other circumstances, or for re-use in other publications, or for translation or adaptation, permission must be secured and a fee may be charged. -

Gender and Generation in the Sahrawi Struggle for Decolonisation

REGENERATING REVOLUTION: Gender and Generation in the Sahrawi Struggle for Decolonisation by Vivian Solana A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Anthropology in a Collaborative with the Women and Gender Studies Institute University of Toronto © Copyright by Vivian Solana, 2017 Regenerating Revolution: Gender and Generation in the Sahrawi Struggle for Decolonisation Vivian Solana Department of Anthropology in a Collaborative with the Women and Gender Studies Institute University of Toronto 2017 Abstract This dissertation investigates the forms of female labour that are sustaining and regenerating the political struggle for the decolonization of the Western Sahara. Since 1975, the Sahrawi national liberation movement—known as the POLISARIO Front—has been organizing itself, while in exile, into a form commensurable with the global model of the modern nation-state. In 1991, a UN mediated peace process inserted the Sahrawi struggle into what I describe as a colonial meantime. Women and youth—key targets of the POLISARIO Front’s empowerment policies—often stand for the movement’s revolutionary values as a whole. I argue that centering women’s labour into an account of revolution, nationalism and state-building reveals logics of long duree and models of female empowerment often overshadowed by the more “spectacular” and “heroic” expressions of Sahrawi women’s political action that feature prominently in dominant representations of Sahrawi nationalism. Differing significantly from globalised and modernist valorisations of women’s political agency, the model of female empowerment I highlight is one associated to the nomadic way of life that predates a Sahrawi project of revolutionary nationalism. -

Download (335Kb)

FORUM of PhD CANDIDATES János Besenyő THE OCCUPATION OF WESTERN SAHARA BY MOROCCO AND MAURITANIA With the myriad of post–colonial conflicts that have and continue to afflict the African continent, it is seldom known that the longest running of these is that between Morocco and the Polisario Front on Western Sahara. The objective of this article to examine the roots of the conflict and provide some information about the occupation of Western-Sahara in 1975. The crisis over Western Sahara started in the early 1970s when Spain was forced to announce plans to withdraw from the territory it had effectively occupied since 1934. Both Morocco and Mauritania lodged claims to those parts of the territory they had occupied, considering them to have been part of their countries well before the Spanish occupation. To these two countries therefore, their move was one of ‘recovery’ rather than ‘occupation’.1 The main causes of the conflict in Western Sahara may be encapsulated broadly in three interrelated categories: politics, economy and geopolitics. The political aspect relates to the Moroccan ideology of “Greater Morocco” which in the early 1960s, in defiance of the principle of uti possidetis juris (inviolability or sanctity of the borders inherited from the colonial era), espoused the idea of a greater pre-colonial Morocco extending over the territory of the Spanish Sahara, parts of present-day Algeria, Mauritania, Mali and Senegal.2 Mauritania’s involvement in the conflict was precisely due to the fear of its government that, after occupying Western Sahara, Morocco would continue its march southwards and eventually annex Mauritania as well.3 1 Ian Brownlie, Ian R. -

EXILE, CAMPS, and CAMELS Recovery and Adaptation of Subsistence Practices and Ethnobiological Knowledge Among Sahrawi Refugees

EXILE, CAMPS, AND CAMELS Recovery and adaptation of subsistence practices and ethnobiological knowledge among Sahrawi refugees GABRIELE VOLPATO Exile, Camps, and Camels: Recovery and Adaptation of Subsistence Practices and Ethnobiological Knowledge among Sahrawi Refugees Gabriele Volpato Thesis committee Promotor Prof. Dr P. Howard Professor of Gender Studies in Agriculture, Wageningen University Honorary Professor in Biocultural Diversity and Ethnobiology, School of Anthropology and Conservation, University of Kent, UK Other members Prof. Dr J.W.M. van Dijk, Wageningen University Dr B.J. Jansen, Wageningen University Dr R. Puri, University of Kent, Canterbury, UK Prof. Dr C. Horst, The Peace Research Institute, Oslo, Norway This research was conducted under the auspices of the CERES Graduate School Exile, Camps, and Camels: Recovery and Adaptation of Subsistence Practices and Ethnobiological Knowledge among Sahrawi Refugees Gabriele Volpato Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of doctor at Wageningen University by the authority of the Rector Magnificus Prof. Dr M.J. Kropff, in the presence of the Thesis Committee appointed by the Academic Board to be defended in public on Monday 20 October 2014 at 11 a.m. in the Aula. Gabriele Volpato Exile, Camps, and Camels: Recovery and Adaptation of Subsistence Practices and Ethnobiological Knowledge among Sahrawi Refugees, 274 pages. PhD thesis, Wageningen University, Wageningen, NL (2014) With references, with summaries in Dutch and English ISBN 978-94-6257-081-8 To my mother Abstract Volpato, G. (2014). Exile, Camps, and Camels: Recovery and Adaptation of Subsistence Practices and Ethnobiological Knowledge among Sahrawi Refugees. PhD Thesis, Wageningen University, The Netherlands. With summaries in English and Dutch, 274 pp. -

QJ Summer 2017

ISSN 1812-1098, e-ISSN 1812-2973 CONNECTIONS THE QUARTERLY JOURNAL Vol. 16, no. 3, Summer 2017 Partnership for Peace Consortium of Defense Creative Commons Academies and Security Studies Institutes BY-NC-SA 4.0 Connections: The Quarterly Journal ISSN 1812-1098, e-ISSN 1812-2973 https://doi.org/10.11610/Connections.16.3 Contents Vol. 16, no. 3, Summer 2017 Research Articles Image of Security Sector Agencies as a Strategic 5 Communication Tool Iryna Lysychkina Guerrilla Operations in Western Sahara: The Polisario versus 23 Morocco and Mauritania János Besenyő The South Caucasus: A Playground between NATO and Russia? 47 Elman Nasirov, Khayal Iskandarov, and Sadi Sadiyev Arms Control Arrangements under the Aegis of the OSCE: Is 57 There a Better Way to Handle Compliance? Pál Dunay British Positions towards the Common Security and Defence 73 Policy of the European Union Irina Tsertsvadze Partnership for Peace Consortium of Defense Creative Commons Academies and Security Studies Institutes BY-NC-SA 4.0 Connections: The Quarterly Journal ISSN 1812-1098, e-ISSN 1812-2973 Iryna Lysychkina, Connections QJ 16, no. 3 (2017): 5-22 https://doi.org/10.11610/Connections.16.3.01 Research Article The Image of Security Sector Agencies as a Strategic Communication Tool Iryna Lysychkina National Academy, National Guard of Ukraine, Kharkiv, Ukraine Abstract: This article highlights the corporate image as a strategic com- munication tool for security sector agencies. The prospects of image for a security sector agency are outlined with regard to image formation and reparation. Image formation is based on the principles of objectivity, openness, credibility and trust whilst avoiding deception and manipula- tion. -

Nowhere to Turn Report

NOWHERE TO TURN: THE CONSEQUENCES OF THE FAILURE TO MONITOR HUMAN RIGHTS VIOLATIONS IN WESTERN SAHARA AND TINDOUF REFUGEE CAMPS NOWHERE TO TURN: THE CONSEQUENCES OF THE FAILURE TO MONITOR HUMAN RIGHTS VIOLATIONS IN WESTERN SAHARA AND TINDOUF REFUGEE CAMPS ROBERT F. KENNEDY CENTER FOR JUSTICE AND HUMAN RIGHTS 2 NOWHERE TO TURN: THE CONSEQUENCES OF THE FAILURE TO MONITOR HUMAN RIGHT VIOLATIONS IN WESTERN SAHARA AND TINDOUF REFUGEE CAMPS I. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS The Sahrawi are the indigenous people of Western Sahara, who descended from Berber and Arab tribes.1 The following is a report on the human rights situation facing the Sahrawi people who reside in the disputed territory of Western Sahara under Moroccan control and in the Sahrawi refugee camps near Tindouf, Algeria. Much of the information contained in this report is based on information gained from interviews and meetings during a visit to the region of an international delegation led by the Robert F. Kennedy Center for Justice and Human Rights (RFK Center). For nearly 40 years, both the Kingdom of Morocco and the Popular Front for the Liberation of Saguía el Hamra and Río de Oro (POLISARIO Front) have claimed sovereignty over Western Sahara, a former Spanish colony. After years of armed conflict, in 1991 the United Nations (UN) established the Mission for the Referendum in Western Sahara (MINURSO), a peacekeeping mission to oversee the cease-fire between the Kingdom of Morocco and the POLISARIO Front and to organize and ensure a referendum on self-determination. Today, 22 years after the establishment of MINURSO, the referendum has yet to take place. -

Saharawi Refugees Camps-Tindouf- Algeria Humanitarian Situation Report #2

Saharawi Refugees Camps-Tindouf- Algeria Humanitarian Situation Report #2 Highlights SITUATION IN NUMBERS Date: 22/08/2016 The effects of the storm that hit the Sahrawi refugee camp of Laayoun on 15 August UNICEF’s Response with partners combined with the return of high temperature, resulted in more of the damaged mud houses and other infrastructure to collapse. This increased the number of 849 houses damaged and of people affected by the emergency. # Families directly affected by total or partial destruction of their homes The latest assessment by UN agencies, NGOs and the Sahrawi Red Crescent raised the number of families directly affected to a total of 849 families (an estimated 8109 4,245 people), of whom 406 families lost their homes and are relying on the # Children under 18 at risk of not being able solidarity of their neighbors for shelter. to go back to school In addition to the 6 out of 8 schools that were damaged, 5 kindergartens out of 7 UNICEF funding needs: also suffered damages, with about 80% of all school-age children (8,109 children) on-going assessment at risk of not accessing education. (*) from assessment as of 22/08 UNICEF, in collaboration with education authorities, visited all the affected school sites and agreed on contingency measures so children can go back to school on 6 September, the first day of school. Detailed planning for and costing of rehabilitation works are under way. Situation Overview & Humanitarian Needs A strong storm accompanied by heavy rains hit Laayoune Camp on 15 August, one of the 5 Sahrawi refugee camps near Tindouf.