The Eighteenth-Century Coin Hoard from Pillaton Hall, Staffs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lower Drayton Farm AD Plant, Penkridge, Stafford, ST19 5RE 20

Lower Drayton Farm AD Plant, Penkridge, Stafford, ST19 5RE 20-145/NMP/v2 - Noise Management Plan 25th August 2020 inacoustic | bristol Caswell Park, Caswell Lane, Clapton-in-Gordano, Bristol, BS20 7RT 0117 325 3949 | [email protected] | www.inacoustic.co.uk inacoustic is a trading name of ABRW Associates Ltd, registered in the UK 09382861 Version 1 Comments Noise Management Plan Agent Comments Date 24th August 2020 25th August 2020 Antony Best BSc (Hons) Antony Best BSc (Hons) Authored By MIOA MIOA Checked By Neil Morgan MSc MIOA Neil Morgan MSc MIOA Project 20-145/NMP/v1 20-145/NMP/v2 Number This report has been prepared for the titled project or named part thereof and should not be used in whole or part and relied upon for any other project without the written authorisation of the author. No responsibility or liability is accepted by the author for the consequences of this document if it is used for a purpose other than that for which it was commissioned. Persons wishing to use or rely upon this report for other purposes must seek written authority to do so from the owner of this report and/or the author and agree to indemnify the author for any loss or damage resulting there from. The author accepts no responsibility or liability for this document to any other party than the person by whom it was commissioned. The findings and opinions expressed are relevant to the dates of the site works and should not be relied upon to represent conditions at substantially later dates. -

Issue 4: How Should the Overall Pattern of Waste Management Facilities in Staffordshire and Stoke- On-Trent Be Defined?

Staffordshire & Stoke-on-Trent Joint Waste Core Strategy Interim SA of Draft Issues and options Sept 2008 Issue 4 : How should the overall pattern of waste management facilities in Staffordshire and Stoke- on-Trent be defined? Appraisal scoring system Symbol Meaning ++ Significant positive effect on sustainability objective (normally direct) + Minor positive effect on sustainability objective (normally indirect) 0 Neutral effect on sustainability objective - Minor negative effect on sustainability objective (normally indirect) -- Significant negative effect on sustainability objective (normally direct) ? Uncertain effect on sustainability objective N/A Not relevant to sustainability objective 1 Staffordshire & Stoke-on-Trent Joint Waste Core Strategy Interim SA of Draft Issues and options Sept 2008 Issue 5: It is proposed that as a general principle the development of additional waste management facilities primarily occurs within or in close proximity to urban areas, following the hierarchy of urban areas as defined in the draft West Midlands RSS. SA Objectives Score Comments 1. Deliver sustainable development through driving N/A Issue 5 is concerned with the location of additional waste management facilities in Staffordshire waste management up the waste hierarchy and Stoke-on-Trent, as opposed to the type of waste management facility. As such, the location of future waste management facilities is not relevant to driving waste management up the waste hierarchy. 2. Encourage schemes that contribute to self sufficiency ++ The location of additional waste management facilities within or in close proximity to major urban in waste treatment and encourage local communities to areas and settlements will encourage local communities to take more responsibility for the waste take responsibility for the waste that they generate they generate, as urban areas in Staffordshire and Stoke-on-Trent are where the greatest amount of waste is produced. -

Mutual Exchange Register

Mutual Exchange Register Current Property Exchange Bedrooms Current Address Name Type Type Contact Details Required Bedrooms Preferred Areas UPIN Current Number of Bedrooms : 0 5 Collingwood Court, Lichfield Miss L BEDSIT BUNG/FLAT 07555294680 1/2 0 Brocton Road, Stone, Staffordshire, ST15 Whistance 8NB [email protected] Burton Manor Coton Fields Doxey Eccleshall Stafford Town Stone Town Walton Walton On The Hill Weston 69 Park Street, Uttoxeter, ST14 Miss Z Mason BEDSIT BUNG/FLAT 07866768058 1/2 0 Great Haywood 7AQ 07943894962 Highfields 07974618362 Newport [email protected] Rising Brook [email protected] Stafford Town 29 Graiseley Street, Miss D Toovey OTHER HSE 07549046902 2 0 Homcroft Wolverhampton, WV30PA [email protected] North End [email protected] Mutual Exchange Register Current Property Exchange Bedrooms Current Address Name Type Type Contact Details Required Bedrooms Preferred Areas CurrentUPIN Number of Bedrooms : 1 10 Hall Close, Silkmore, Stafford, Mrs K Brindle FLAT BUNG 07879849794 1 1 Barlaston Staffordshire, ST17 4JJ [email protected] Beaconside Rickerscote Silkmore Stafford Town Stone Town 10 Wayside, Pendeford, Mr P Arber FLAT BUNG/FLAT 07757498603 1 1 Highfields Wolverhampton , WV81TE 07813591519 Silkmore [email protected] 12 Lilac Grove, Chasetown, Mr C Jebson BUNG BUNG/FLAT [email protected] 1 1 Eccleshall Burntwood, WS7 4RW Gnosall Newport 12 Penkvale Road, Moss Pit, Mrs D Shutt FLAT BUNG 01785250473 1 1 Burton Manor Stafford, Staffordshire, ST17 -

Baseline Report: Climate Change Mitigation & Adaptation Study

Baseline Report Climate Change Adaptation & Mitigation Staffordshire County Council Project number: 60625972 16 October 2020 Revision 04 Baseline Report Project number: 60625972 Quality information Prepared by Checked by Verified by Approved by Harper Robertson Luke Aldred Luke Aldred Matthew Turner Senior Sustainability Associate Director Associate Director Regional Director Consultant Alice Purcell Graduate Sustainability Consultant Luke Mulvey Graduate Sustainability Consultant Revision History Revision Revision date Details Authorized Name Position 01 20 February 2020 Skeleton Report Y Luke Associate Aldred Director 02 31 March 2020 Draft for issue Y Luke Associate Aldred Director 03 11 September 2020 Final issue Y Luke Associate Aldred Director 04 16 October 2020 Updated fuel consumption Y Luke Associate and EV charging points Aldred Director Distribution List # Hard Copies PDF Required Association / Company Name Prepared for: Staffordshire County Council AECOM Baseline Report Project number: 60625972 Prepared for: Staffordshire County Council Prepared by: Harper Robertson Senior Sustainability Consultant E: [email protected] AECOM Limited Aldgate Tower 2 Leman Street London E1 8FA United Kingdom aecom.com © 2020 AECOM Infrastructure & Environment UK Limited. All Rights Reserved. This document has been prepared by AECOM Infrastructure & Environment UK Limited (“AECOM”) for sole use of our client (the “Client”) in accordance with generally accepted consultancy principles, the budget for fees and the terms of reference agreed between AECOM and the Client. Any information provided by third parties and referred to herein has not been checked or verified by AECOM, unless otherwise expressly stated in the document. No third party may rely upon this document without the prior and express written agreement of AECOM. -

Curacy in the Diocese of Lichfield

Curacy in the Diocese of Lichfield Title post in the St Mary’s | inclusive catholic a town centre church with a civic role at parishes of the heart of the county Saint Mary’s, Stafford St Chad’s | inculsive catholic an ancient High Street parish with a Saint Chad’s, Stafford ministry to the shopping area centre Saint Leonard’s, St Leonard’s | central a small rural church on the route of HS2 Marston with a new parish being built around it Welcome to Lichfield Diocese Cradled at the intersection of the Midlands and the Shropshire, to the sparsest upland communities of North, and the interface between England and the Staffordshire Moorlands and Welsh Borders. Wales, the Diocese of Lichfield is the ancient centre And we embrace the widest spectrum of church of Christianity in what was the Kingdom of Mercia. traditions – evangelical and catholic, liberal and We are rightfully grateful for the inheritance we conservative, choral and charismatic, as we journey have from St Chad that leads us to focus on together – as a colleague recently put it, it is our Discipleship, Vocation and Evangelism as we live goal to be a ‘spacious and gracious diocese’. and serve among the communities of Staffordshire, northern Shropshire and the Black Country. ‘…a spacious and Wherever in the Diocese you may be placed, you will benefit from being part of a wider family, gracious diocese.’ mixing with people serving in a wide variety of contexts – from the grittiest inner-city It is my determination and that of my fellow- neighbourhoods of Stoke and the Black Country, to bishops that your calling to a title post will be a the leafiest rural parishes of Staffordshire and time of encouragement, ongoing formation, challenge and (while rarely unbridled) joy. -

Cannock + Stafford Network Map 2018

M 6 M o t o r w Beaconsid e a A513 y Redhill Business Park 8A Parkside andon R S oad P e. ar ide Av e ks n 4 La 3 A l ab il 8A Cr dh 8 e R C re sw S G a e S r n o ll t o v d e n o e n R R o o ad a S d e c 8 o n d Creswell A v 8A en u Holmcroft e t E c Holmcrodf c oa d le R a s 8 h Ro a 1 l l 5 n R A o o a d n d S B t a e o S ac n o e n s id Tillington A Ro stonfiel e ds Rd a . d s ad n e o d R r d a a n o G d o R r d a st r 8 r n o h o c . a f d x n e n v M a O e r A Po 8A S Do T rta ug l R . la d. s Rd. Ted reensom Ave de G e C pect r F o ros R R L o r P oa oa a r p d d n Doxey e o g r e at Grey-Friars at ked i Read Croo on e Stafford County Hospital 12 Retail Park . Rd S S idge tr S terminating: t Br e m r e e G n e t al d a e a S l L t t m a o re a o 74 825 l e n s R d R t r D a o d xe n y y . -

Memorials of Old Staffordshire, Beresford, W

M emorials o f the C ounties of E ngland General Editor: R e v . P. H. D i t c h f i e l d , M.A., F.S.A., F.R.S.L., F.R.Hist.S. M em orials of O ld S taffordshire B e r e s f o r d D a l e . M em orials o f O ld Staffordshire EDITED BY REV. W. BERESFORD, R.D. AU THOft OF A History of the Diocese of Lichfield A History of the Manor of Beresford, &c. , E d i t o r o f North's .Church Bells of England, &■V. One of the Editorial Committee of the William Salt Archaeological Society, &c. Y v, * W ith many Illustrations LONDON GEORGE ALLEN & SONS, 44 & 45 RATHBONE PLACE, W. 1909 [All Rights Reserved] T O T H E RIGHT REVEREND THE HONOURABLE AUGUSTUS LEGGE, D.D. LORD BISHOP OF LICHFIELD THESE MEMORIALS OF HIS NATIVE COUNTY ARE BY PERMISSION DEDICATED PREFACE H ILST not professing to be a complete survey of Staffordshire this volume, we hope, will W afford Memorials both of some interesting people and of some venerable and distinctive institutions; and as most of its contributors are either genealogically linked with those persons or are officially connected with the institutions, the book ought to give forth some gleams of light which have not previously been made public. Staffordshire is supposed to have but little actual history. It has even been called the playground of great people who lived elsewhere. But this reproach will not bear investigation. -

Timetables from 2020-09-01.Xlsx

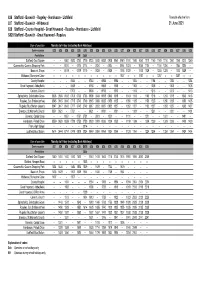

826 Stafford - Baswich - Rugeley - Handsacre - Lichfield Timetable effective from: 827 Stafford - Baswich - Wildwood 21 June 2021 828 Stafford - County Hospital - Great Haywood - Rugeley - Handsacre - Lichfield S828 Stafford - Baswich - Great Haywood - Rugeley Days of operation Monday to Friday (excluding Bank Holidays) Service number 828 828 826 828 826 826 828 826 828 826 828 827 826 828 827 826 828 827 826 828 827 826 828 Restrictions SH Sch Stafford, Gaol Square – – 0600 0630 0700 0700 0730 0805 0835 0905 0940 0940 1010 1040 1040 1110 1140 1140 1210 1240 1240 1310 1340 Queensville, Queens Shopping Park – – 0614 – 0714 0714 – 0824 – 0924 – 0954 1024 – 1054 1124 – 1154 1224 – 1254 1324 – Baswich, Shops – – 0619 – 0719 0719 – 0829 – 0929 – 1003 1029 – 1103 1129 – 1203 1229 – 1303 1329 – Wildwood, Stonepine Close – – –––––––––1007 – – 1107 – – 1207 – – 1307 – – County Hospital – – – 0644 – – 0744 – 0854 – 0954 – – 1054 – – 1154 – – 1254 – – 1354 Great Haywood, Abbeyfields – – – 0658 – – 0758 – 0908 – 1008 – – 1108 – – 1208 – – 1308 – – 1408 Colwich, Church – – – 0703 – – 0803 – 0913 – 1013 – – 1113 – – 1213 – – 1313 – – 1413 Springfields, Grindcobbe Grove 0538 0608 0633 0708 0733 0733 0808 0843 0918 0943 1018 – 1043 1118 – 1143 1218 – 1243 1318 – 1343 1418 Rugeley, Bus Station (arrive) 0545 0615 0640 0715 0740 0740 0815 0850 0925 0950 1025 – 1050 1125 – 1150 1225 – 1250 1325 – 1350 1425 Rugeley, Bus Station (depart) 0547 0617 0642 0717 0742 0742 0817 0852 0927 0952 1027 – 1052 1127 – 1152 1227 – 1252 1327 – 1352 1427 Brereton, St Michael's -

Brewood and Coven Parish Council

BREWOOD AND COVEN PARISH COUNCIL with Bishops Wood and Coven Heath 35 Stafford Street, Brewood, Stafford, ST19 9DX Tel/Fax: 01902 850809 Email: [email protected] Website: www.brewoodandcovenparish.org.uk Opening times: 9.30am to 12.30pm, other times by arrangement Clerk to the Council: Mrs M. Birtles PSLCC Mr K. O’Hanlon Department for Transport Great Minster House 33 Horseferry Road London SW1P 4DR 6 February 2020 Dear Mr O’Hanlon The Parish Council would like to take the opportunity to respond to the correspondence received from the Department for Transport date 24 January 2020 regarding the letter to the Secretary of State from Eversheds Sutherland (International) LLP. This Parish Council, on behalf of its residents, is totally opposed to the West Midlands Interchange. However, should the Secretary of State decide that this plan is to be approved, the Parish Council would like to see strict conditions applied in order to ensure that the rail link is in place before more than 25% of the warehousing is built and occupied. Failure to not have a rail link as a priority will greatly increase the volume of traffic on all the roads, major and minor in and around the area which will have a serious effect on local people’s lives and the on the natural environment. Any decisions taken with regard to the Northampton Gateway, the East Midlands Gateway or indeed any other Development Consent Order should not automatically impact the Four Ashes site. In addition to 13 Parish Councils, South Staffordshire Council and two MPs, over 1,800 individuals, a significant number of people given its rural location, are totally opposed to this development and would petition that the development be refused in its entirety. -

Name of Deceased (Surname First) Address, Description and Date Of

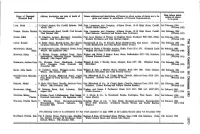

Date before which Name of Deceased Address, description and date of death of Names, addresses and descriptions of Persons to whom notices of claims are to be notices of claims (Surname first) Deceased given and names, in parentheses, of Personal Representatives to be given LAYE, Doris 21 Grand Avenue, Ely, Cardiff, Spinster. 24th John Loosemore and Company, Alliance House, 18-19 High Street, Cardiff. 2nd February 1984 March, 1983. (Mabel Emily Dancey.) (Wlows) (156) PARKER, Marion Patricia 53A Marlborough Road, Cardiff, Civil Servant. John Loosemore and Company, Alliance House, 18-19 High Street, Cardiff. 14th February 1984 22nd October 1983. (Paul Malcolm Trenchard and Pamela Anne Cowburn.) (Wlows) (157) OGDEN, Edith 32 Kingston Avenue, Blackpool, Lancashire, Peck Lewis Belshaw & Watson, 24 Hoghton Street, Southport PR9 OXH. (Brian 2nd February 1984 Spinster. 22nd November 1983. Richard Farrington and John Michael Ogden.) (Wlows) (158) LOFTS, Ronald 47 Sidley Street, Bexhill-on-Sea, East Sussex, Shuttleworth & Co., 21 Eversley Road, Bexhill-on-Sea, East Sussex. (Anthony 15th February 1984 Carpenter (Retired). 9th November 1983. Colin Shuttleworth and John Edward Straker Crone.) (Wlows) (159) BRITCHFORD, Gladys 28 Bartholomew Lane, Saltwood, Hythe, Kent, Stilwell & Harby, 8 Douglas Avenue, Hythe, Kent CT21 5JT. (Kenneth Leslie 5th February 1984 Mary. Widow. 6th September 1983. Malpass and Sonia Louise Malpass.) (Wlows) (160) RANDVIIR, Elmar 57 Walton Grange, Stafford Road, Stone, Walters and Welch, 9 Station Road, Stone, Staffordshire ST15 8JS, Solicitors. 17th February 1984 Staffordshire, Operating Theatre Technician (Dianne Elizabeth Kodis.) .(Wlows)(161) (Retired). 14th August 1983. BURBRIDGE, Andrew Gray 57s Mycenae Road, Blackheath, London Weigall & Inch, 2 Hawley Street, Margate, Kent CT9 IPS. -

Introduction Newcastle-Under-Lyme College Officially Merged With

Introduction Newcastle-under-Lyme College officially merged with Stafford College on November 1st 2016 as a type B merger. The College Group includes Newcastle-under-Lyme College, Stafford College, Axia Training Solutions and Gradbach Farmhouse and Mill all now form part of NSCG: Newcastle and Stafford Colleges Group. Newcastle-under-Lyme College Newcastle-under-Lyme College is a tertiary college, the only one of its kind serving Staffordshire. The most sizeable part of its provision is the delivery of a wide range of vocational and academic programmes for 16-18 year olds. However, the offer is also typical of a medium sized General Further Education college and provision includes a substantial programme of Apprenticeship training; workplace learning for young people and adults; adult classroom based learning; higher education and provision for the unemployed. The College has grown significantly over the past 10 years and caters for a population of circa 3,600 full- time and nearly 1,700 part time students on its main site. Overall growth has continued each year since the College was built in 2010 and boasts some of the most advanced facilities in the country and is an attractive place to learn. The College draws students in approximately equal measure from Newcastle-under-Lyme, a North Staffordshire town with a population of 127,000, and the conurbation of Stoke-on-Trent, with a population of 249,000. The College is the single biggest provider of 16-18 education in North Staffordshire recruiting in almost equal numbers from the Stoke-on-Trent and Newcastle-under-Lyme areas. -

Burntwood Burton on Trent Cannock Leek Lichfield

Staffordshire Pharmacy Opening Times Summer Bank Holiday 2019 Telephone Summer Bank Holiday Number Mon 26 August 2019 BURNTWOOD Day Night Pharmacy, Swan Island Shopping, Chase Rd, Burntwood, WS7 0DW 01543 676952 13:00-15:00 BURTON ON TRENT Asda Pharmacy, Octagon Centre, Orchard Street, Burton on Trent, DE14 3TN 01283 523210 09:00-18:00 Boots the Chemist, 1 Cooper Square, Burton on Trent, DE14 1DG 01283 561573 10:00-16:00 Lloyds Pharmacy, (Sainsbury’s), Union Street, Burton on Trent, DE14 1AA 01283 569431 09:00-17:00 Morrisons Pharmacy, Wellington Road, Burton on Trent, DE14 2AR 01283 563947 10:00-16:00 Tesco Pharmacy, Tesco Superstore, St Peters Brdg, Burton on Trent, DE14 3RJ 01283 614010 12:00-16:00 CANNOCK Boots the Chemist, Unit 9, Orbital Retail Park, Cannock, WS11 8XP 01543 579863 10:00-14:30 15:00-16:00 Lloyds Pharmacy, (Sainsbury’s), Voyager Dv, Orbital Retail, Cannock, WS11 8XP 01543 437481 09:00-17:00 Tesco Pharmacy, Victoria Shopping Pk, Victoria St, Hednesford, WS12 1DW 01543 801003 12:00-16:00 Tesco Pharmacy, Hawks Green District Ctr, Heath Hayes, Cannock, WS12 3YY 01543 801000 12:00-16:00 LEEK Lloyds Pharmacy (Sainsbury’s), Churnet Way, Macclesfield Rd, Leek, ST13 8YG 01538 372493 09:00-17:00 LICHFIELD Boots the Chemist, Waitrose Supermarket, Stonnyland Dv, Lichfield, WS13 6RX 01543 253994 10:00-16:00 Boots the Chemist, 4-8 Tamworth Street, Lichfield, WS13 6JJ 01543 263149 10:00-16:00 Tesco Pharmacy, Tesco Superstore, Church Street, Lichfield, WS13 6DZ 0121 5197698 12:00-16:00 NEWCASTLE UNDER LYME Asda Pharmacy, Wolstanton