Snow Tha Product

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

This Interview Is Being Conducted on Barry Chism. Let's Start with The

This interview is being conducted on Barry Chism. Let's start with the beginning of your life. When were you born? Mr. Chism: I was born on May 21, 1925, about a mile and a half south of here in Greenbrier, Tennessee and I haven't been afar from this spot forever. With the exception of going to war... Mr. Chism: Well that was not voluntary, but I did go. I was kind of hoping and kind of hoping and kind of thinking that the war was going to end before I got into it because of my age. I was drafted a twenty-five year old man and pretty soon they dropped it down to a twenty-one year man and I thought that I was still in pretty good shape. I wasn't twenty-one yet but I was still in high school. I believe it was in 1942 that they dropped the draft age down to eighteen. But they guaranteed you; supposedly, a year’s training before you go overseas. That was in the bill that passed by our lawmakers at that time. No person under the age of nineteen would be sent overseas. I still thought I was in pretty good shape. So I did manage to graduate from high school, then the draft got me. I wound up beginning to take basic training at Fort McClellan, Alabama. But first they pick you up and send you to what is called a reception center. I don’t know why they call those things reception centers. We didn't get such a good reception there. -

Refugee: Reading Neoliberal Critique and Refugee Narratives Through

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles “Bad Gal” and the “Bad” Refugee: Reading Neoliberal Critique and Refugee Narratives through Cambodian Canadian Hip Hop A thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Asian American Studies by Kenneth Wing Lun Chan 2016 ABSTRACT OF THESIS “Bad Gal” and the “Bad” Refugee: Reading Neoliberal Critique and Refugee Narratives through Cambodian Canadian Hip Hop by Kenneth Wing Lun Chan Master of Arts in Asian American Studies University of California, Los Angeles, 2016 Professor Victor Bascara, Chair This project examines the intersections of refugee discourses and neoliberal critique through the analysis of the 2013 hip hop music video “Bad Gal” by Cambodian Canadian artist Honey Cocaine. By utilizing the concept of the “bad refugee” as a subjectivity that refuses to reconcile imperialist wars in Southeast Asia, rejects developmental narratives of progress and uplift, and contradicts neoliberal multiculturalism, this project demonstrates how “Bad Gal” is a countersite that reveals neoliberal ruptures. I observe “Bad Gal” for its audiovisual content, use of digital editing techniques, and themes of deviance and blackness, in arguing that it expresses an alternative refugee narrative and temporality, and a refusal of neoliberal subjectivity through the identifications of blackness and hip hop. This project draws from Critical Refugee Studies, cultural studies, and comparative racialization scholars in delineating the processes of gendered racialization for the Cambodian refugee diaspora, and the ways in which cultural productions provide a lens in understanding their relationship to the neoliberal state. ii The thesis of Kenneth Wing Lun Chan is approved. -

Regional Oral History Office University of California the Bancroft Library Berkeley, California

Regional Oral History Office University of California The Bancroft Library Berkeley, California Faith Traversie Rosie the Riveter World War II American Homefront Oral History Project A Collaborative Project of the Regional Oral History Office, The National Park Service, and the City of Richmond, California Interviews conducted by Elizabeth Castle in 2005 Copyright © 2007 by The Regents of the University of California Since 1954 the Regional Oral History Office has been interviewing leading participants in or well-placed witnesses to major events in the development of Northern California, the West, and the nation. Oral History is a method of collecting historical information through tape-recorded interviews between a narrator with firsthand knowledge of historically significant events and a well-informed interviewer, with the goal of preserving substantive additions to the historical record. The tape recording is transcribed, lightly edited for continuity and clarity, and reviewed by the interviewee. The corrected manuscript is bound with photographs and illustrative materials and placed in The Bancroft Library at the University of California, Berkeley, and in other research collections for scholarly use. Because it is primary material, oral history is not intended to present the final, verified, or complete narrative of events. It is a spoken account, offered by the interviewee in response to questioning, and as such it is reflective, partisan, deeply involved, and irreplaceable. ********************************* All uses of this manuscript are covered by a legal agreement between The Regents of the University of California and Faith Traversie. The manuscript is thereby made available for research purposes. All literary rights in the manuscript, including the right to publish, are reserved to The Bancroft Library of the University of California, Berkeley. -

Midwest Choppers 2 Download Free

Midwest choppers 2 download free Artist: Tech N9ne, Song: Midwest Choppers 2 [extended](feat. K-Dean, Krayzie Bone, Twista), Duration: , Size: MB, Bitrate: kbit/sec, Type: mp3. Krayzie Bone & K-Dean) Tech N9ne - Midwest Chopper ツ Tech N9neツ - Midwest Choppers ft. D-Loc, Dalima & Big Kriz Tech N9ne - Midwest Choppers 2(feat. Midwest Choppers 2 by Tech N9ne feat. K-Dean and Krayzie We are considering introducing an ad-free version of WhoSampled. If you would be happy to pay. Stream Tech N9ne Midwest Choppers 2 Lyrics by yancydaveoo17 from desktop or your mobile device. Download. Tech N9ne - Midwest Choppers 2. Download. Tech N9ne - Midwest Choppers (feat. Big Krizz Kaliko, Dalima & D-Loc). Download. Tech N9ne "Midwest Choppers 2" ft. K-Dean & Krayzie Bone iTunes - Official Hip Hop. Midwest Choppers 2 Mp3. Free download Midwest Choppers 2 Mp3 mp3 for free. Tech N9ne - Midwest Choppers 2 (ft. K-Dean & Krayzie Bone). Source. View Lyrics for Midwest Choppers 2 by Tech N9ne at AZ Lyrics Sickology Midwest Choppers 2 AZ lyrics, find other albums and lyrics for Tech. Switch browsers or download Spotify for your desktop. Midwest Choppers 2. By Tech N9ne Collabos. • 1 song, Play on Spotify. 1. Midwest Choppers. Buy Midwest Choppers 2 [Clean]: Read 2 Digital Music Reviews - Buy Midwest Choppers 2 [Explicit]: Read 2 Digital Music Reviews - Start your day free trial of Unlimited to listen to this song plus tens of. Fast and free Tech N9ne Midwest Choppers Instrumental YouTube to MP3. Midwest Choppers 2 Remake On Fl Studio 9(instrumental)-unfinished (OLD) Tech N9ne - Worldwide Choppers FULL Instrumental Remake (with download link). -

Smith, Troy African & African American Studies Department

Fordham University Masthead Logo DigitalResearch@Fordham Oral Histories Bronx African American History Project 2-3-2006 Smith, Troy African & African American Studies Department. Troy Smith Fordham University Follow this and additional works at: https://fordham.bepress.com/baahp_oralhist Part of the African American Studies Commons Recommended Citation Smith, Troy. Interview with the Bronx African American History Project. BAAHP Digital Archive at Fordham University. This Interview is brought to you for free and open access by the Bronx African American History Project at DigitalResearch@Fordham. It has been accepted for inclusion in Oral Histories by an authorized administrator of DigitalResearch@Fordham. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Interviewer: Mark Naison, Andrew Tiedt Interviewee: Troy Smith February 3, 2006 - 1 - Transcriber: Laura Kelly Mark Naison (MN): Hello, this is the 143rd interview of the Bronx African American History Project. It’s February 3, 2006. We’re at Fordham University with Troy Smith who is one of the major collectors of early hip hop materials in the United States and the lead interviewer is Andrew Tiedt, graduate assistant for the Bronx African American History Project. Andrew Tiedt (AT): Okay Troy, first I wanna say thanks for coming in, we appreciate it. Your archive of tapes is probably one of the most impressive I’ve ever seen and especially for this era. Well before we get into that though, I was wondering if you could just tell us a little bit about where you’re from. Where did you grow up? Troy Smith (TS): I grew up in Harlem on 123rd and Amsterdam, the Grant projects, 1966, I’m 39 years old now. -

Dj Issue Can’T Explain Just What Attracts Me to This Dirty Game

MAC MALL,WEST CLYDEOZONE COAST:CARSONPLUS E-40, TURF TALK OZONE MAGAZINE MAGAZINE OZONE FIGHT THE POWER: THE FEDS vs. DJ DRAMA THE SECOND ANNUAL DJ ISSUE CAN’T EXPLAIN JUST WHAT ATTRACTS ME TO THIS DIRTY GAME ME TO ATTRACTS JUST WHAT MIMS PIMP C BIG BOI LIL FLIP THREE 6 MAFIA RICK ROSS & CAROL CITY CARTEL SLICK PULLA SLIM THUG’s YOUNG JEEZY BOSS HOGG OUTLAWZ & BLOODRAW: B.G.’s CHOPPER CITY BOYZ & MORE APRIL 2007 USDAUSDAUSDA * SCANDALOUS SIDEKICK HACKING * RAPQUEST: THE ULTIMATE* GANGSTA RAP GRILLZ ROADTRIP &WISHLIST MORE GUIDE MAC MALL,WEST CLYDEOZONE COAST:CARSONPLUS REAL, RAW, & UNCENSORED SOUTHERN RAP E-40, TURF TALK FIGHT THE POWER: THE FEDS vs. DJ DRAMA THE SECOND ANNUAL DJ ISSUE MIMS PIMP C LIL FLIP THREE 6 MAFIA & THE SLIM THUG’s BOSS HOGG OUTLAWZ BIG BOI & PURPLE RIBBON RICK ROSS B.G.’s CHOPPER CITY BOYZ YOUNG JEEZY’s USDA CAROL CITY & MORE CARTEL* RAPQUEST: THE* SCANDALOUS ULTIMATE RAP SIDEKICK ROADTRIP& HACKING MORE GUIDE * GANGSTA GRILLZ WISHLIST OZONE MAG // 11 PUBLISHER/EDITOR-IN-CHIEF // Julia Beverly CHIEF OPERATIONS OFFICER // N. Ali Early MUSIC EDITOR // Randy Roper FEATURES EDITOR // Eric Perrin ART DIRECTOR // Tene Gooden ADVERTISING SALES // Che’ Johnson PROMOTIONS DIRECTOR // Malik Abdul MARKETING DIRECTOR // David Muhammad LEGAL CONSULTANT // Kyle P. King, P.A. SUBSCRIPTIONS MANAGER // Destine Cajuste ADMINISTRATIVE // Cordice Gardner, Kisha Smith CONTRIBUTORS // Alexander Cannon, Bogan, Carlton Wade, Charlamagne the God, Chuck T, E-Feezy, Edward Hall, Felita Knight, Iisha Hillmon, Jacinta Howard, Jaro Vacek, Jessica INTERVIEWS Koslow, J Lash, Jason Cordes, Jo Jo, Joey Columbo, Johnny Louis, Kamikaze, Keadron Smith, Keith Kennedy, Kenneth Brewer, K.G. -

Visual Metaphors on Album Covers: an Analysis Into Graphic Design's

Visual Metaphors on Album Covers: An Analysis into Graphic Design’s Effectiveness at Conveying Music Genres by Vivian Le A THESIS submitted to Oregon State University Honors College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Honors Baccalaureate of Science in Accounting and Business Information Systems (Honors Scholar) Presented May 29, 2020 Commencement June 2020 AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Vivian Le for the degree of Honors Baccalaureate of Science in Accounting and Business Information Systems presented on May 29, 2020. Title: Visual Metaphors on Album Covers: An Analysis into Graphic Design’s Effectiveness at Conveying Music Genres. Abstract approved:_____________________________________________________ Ryann Reynolds-McIlnay The rise of digital streaming has largely impacted the way the average listener consumes music. Consequentially, while the role of album art has evolved to meet the changes in music technology, it is hard to measure the effect of digital streaming on modern album art. This research seeks to determine whether or not graphic design still plays a role in marketing information about the music, such as its genre, to the consumer. It does so through two studies: 1. A computer visual analysis that measures color dominance of an image, and 2. A mixed-design lab experiment with volunteer participants who attempt to assess the genre of a given album. Findings from the first study show that color scheme models created from album samples cannot be used to predict the genre of an album. Further findings from the second theory show that consumers pay a significant amount of attention to album covers, enough to be able to correctly assess the genre of an album most of the time. -

Key West Oral History Interview with Roosevelt Sands Sr

Title: Key West Oral History Interview with Roosevelt Sands Sr. INTERVIEWEE: Roosevelt Sands Sr. INTERVIEWER: Virginia Irving, Unknown2, and Unknown3 TRANSCRIBER: Andrea Benitez TRANSCIBED: November 13, 2007 INTERVIEW LENGTH: 00:60:25 Irving: -- (?)? Sands: Yeah, Roosevelt Sands Sr. I: Okay. Mr. Sands is a Bahamian descendant, right? S: Yeah, that’s right. I was born here, but my parents were born in the Bahamas. I: Do you remember where they were born? S: Yeah. My father was born in Harbour Island and my mother was born in Bluff, Eleuthera. I: That’s the same place where Mrs. Jones was from-- S: Oh, yeah, yeah, she’s a cousin of mine. I: Bluff, Eleuthera. S: Right. I: We were looking at the map this morning and there’s an island called ‘Eleuthera’-- S: Uh-huh. I: --and we were trying to figure out about Bluff and we were thinking that maybe Bluff was a point on the island where the people lived so they called it ‘Bluff’, Eleuthera. S: That’s correct. I: That’s what we figured out, we don’t know-- S: Yeah, that’s-- I think you’re both right about that. I: What about your grandparents, their names? Do you remember their names? S: My grandparents? Let me see. My mother’s mother was named Mary Davis- my mother was a Davis before she became a Sands. My father-- my grandfather- you know, his father- he was a Sands. He died at a pretty early age; he was a seaman. I don’t recall whether my father knew him or not. -

UC Riverside UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Riverside UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title The Dead and Their Killers Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/1094031m Author Morshed, Michael Publication Date 2013 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE The Dead and Their Killers A Thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts in Creative Writing and Writing for the Performing Arts by Michael Morshed December 2013 Thesis Committee: Professor Tod Goldberg, Co-Chairperson Professor Andrew Winer, Co-Chairperson Professor Rob Roberge The Thesis of Michael Morshed is approved: Committee Co-Chairperson Committee Co-Chairperson University of California, Riverside Chapter Dr. Bill McFarland was dead on his kitchen table by afternoon, but that morning Helen Abraham sat in there with him. She had gone to him to get help with the red insect bites all over her hands. When the kettle whistled, he stood to turn the fire off. Helen thought he had looked closer at the stains on his white coffee mug than he had the spots on her hands. He filled two cups, one for him, and he set the other down in front of Helen. It hurt too much for her to pick the mug up. Dr. Bill McFarland took a sip and cringed. "Hot?" Helen smiled. "It's right off the stove." He set the mug down. "Let me see the hands again." She snapped them shut and they felt clammy. The spots embarrassed her. She extended her hands over the table, spread her fingers, and he turned her hand around. -

Eminem the Hills Remix Download

Eminem the hills remix download CLICK TO DOWNLOAD The Hills (Eminem Remix) Lyrics: Said you want a little company / And I love it, 'cause the thrill’s cheap / Said you left him for good this time / Still if he knew I was here, he’d wanna kill. У нас вы можете бесплатно скачать песню Eminem - The Hills (Remix) в mp3 качестве и прослушать онлайн в плейлисте. Просмотреть другие песни артиста Eminem, а также найти песни похожие по стилю и звучанию. · In addition to Nicki Minaj, Eminem appears on an alternate remix to The Weeknd’s No. 1 hit “The Hills” off Beauty Behind the renuzap.podarokideal.ru Shady, whose guest appearances are few and far. Ascolta 'The Hills (Remix)' di The Weeknd Feat. Eminem. Said you want a little company / And I love it cause the thrill's cheap / Said you left him for good this time. Download "The Weeknd ft Eminem - The Hills Remix [Lyrics] Official Audio" Download video "The Weeknd ft Eminem - The Hills Remix [Lyrics] Official Audio" directly from youtube. Just chose the format and click on the button "Download". After few moments will be generated link to download video and you can start downloading. Free Download The Weeknd Ft Eminem The Hills Remix Lyrics Official renuzap.podarokideal.ru3, Uploaded By:: Rinor Susuri EMINƎM, Size: MB, Duration: 4 minutes and 16 seconds, Bitrate: Kbps. Eminem The Hills Remix Mp3 Download | MB | Somerset Music | renuzap.podarokideal.ru "The Hills (Eminem Remix)" by Eminem is a remix of The Weeknd's "The Hills". Listen to both songs on WhoSampled, the ultimate database of sampled music, cover songs and remixes. -

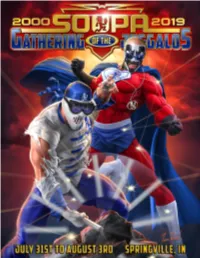

To View the Official Program!

20 years of the gathering of the juggalos... On this momentous occasion, we Gather together not just to celebrate the 20th Annual Gathering of the Juggalos, but to uphold the legacy of our Juggalo Family. For two decades strong, we have converged at the height of the summer season for something so much more than the concerts, the lights, the sounds, the revelry, and the circus. There is no mistaking that the Gathering is the Greatest Show on Earth and has rightfully earned the title as the longest running independent rap festival on this or any other known planet. And while all these accolades are well-deserved and a point of pride, in our hearts we know...There is so much more to this. A greater reason and purpose. A magic that calls us together. That knowing. The spirit of the tribe. The call of the Dark Carnival. The magic mists that float by as we gaze through the trees into starry skies. We are together. And THAT is what we celebrate here, after 20 long, fresh, hilarious, incredible, tremendously karma-filled years. We call this the Soopa Gathering because we are here to celebrate the superpowers of the Juggalo Family. All of us here together and united are capable of heroics and strength beyond measure. We are Soopa. We are mighty. For we have found each other by the magic of the Carnival—standing 20 years strong on the Dirtball as we see into the eternity of Shangri-La. Finding Forever together, may the Dark Carnival empower and ignite the Hero in you ALL.. -

Tech N9ne Godspeed

Godspeed Tech N9ne Kingdom! From this day on I will never - force - anything good Down anybody's throat Now before I start spazzin' I'm a speak in a language That the majority Will understand Niggas see me shinin' They know Tech N9nna the best at the rhymin' Yeah, but they ain't buyin' Strange Music flyin' We steady climbin' I'm still a wanted man I get a hunnid band Still I do Summer Jam Woah! Tecca N9ne milla' Kansas City Killa' Turn up! Bubblin' up with it because a nigga be gassin' Enemy know that I'm ready for action No matter the money we gotta go dummy and with' it so nigga what's happenin' I really come and I do it with passion Whenever I'm in the booth I real as ramen and juicy juice And the vomit induced when the onyx been poop Regroup and spin this shit Learnin' this level of linguistics Lot of you who loose it love lickin' limp bizkits And I am done Tryna shine a star of Donnie to the people like "f**k this nigga" Soundin' will as Farrakhan he Never can raise this bar upon me I am on par with omni Kill every thing in sight before the light say Longevity, haters don't wan' credit me When I'm steadily reachin' people like mom said I'd be They on heavily, like it be gone medically When I'm bustin' on this bitch in the street like Ron Jeremy This song's therapy, strong genetically, bomb palms red if he's blond Here to be 'nouncin' The Don's pedigree I'm a 'gnac linguist With' a black penis I can act meanest 'Cause I'm a rap genius Keepin' 'em crack fiendish Praise K.O.D.