Wahoo, Chief of the Logos

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Castrovince | October 23Rd, 2016 CLEVELAND -- the Baseball Season Ends with Someone Else Celebrating

C's the day before: Chicago, Cleveland ready By Anthony Castrovince / MLB.com | @castrovince | October 23rd, 2016 CLEVELAND -- The baseball season ends with someone else celebrating. That's just how it is for fans of the Indians and Cubs. And then winter begins, and, to paraphrase the great meteorologist Phil Connors from "Groundhog Day," it is cold, it is gray and it lasts the rest of your life. The city of Cleveland has had 68 of those salt-spreading, ice-chopping, snow-shoveling winters between Tribe titles, while Chicagoans with an affinity for the North Siders have all been biding their time in the wintry winds since, in all probability, well before birth. Remarkably, it's been 108 years since the Cubs were last on top of the baseball world. So if patience is a virtue, the Cubs and Tribe are as virtuous as they come. And the 2016 World Series that arrives with Monday's Media Day - - the pinch-us, we're-really-here appetizer to Tuesday's intensely anticipated Game 1 at Progressive Field -- is one pitting fan bases of shared circumstances and sentiments against each other. These are two cities, separated by just 350 miles, on the Great Lakes with no great shakes in the realm of baseball background, and that has instilled in their people a common and eventually unmet refrain of "Why not us?" But for one of them, the tide will soon turn and so, too, will the response: "Really? Us?" Yes, you. Imagine what that would feel like for Norman Rosen. He's 90 years old and wise to the patience required of Cubs fandom. -

Use of Native American Team Names in the Formative Era of American Sports, 1857-1933

BEFORE THE REDSKINS WERE THE REDSKINS: THE USE OF NATIVE AMERICAN TEAM NAMES IN THE FORMATIVE ERA OF AMERICAN SPORTS, 1857-1933 J. GORDON HYLTON* L INTRODUCTION 879 IL CURRENT SENTIMENT 881 III. A BRIEF HISTORY OF NATIVE AMERICAN TEAM NAMES 886 IV. THE FIRST USAGES OF NATIVE AMERICAN TEAM NAMES IN AMERICAN SPORT 890 A. NATIVE AMERICAN TEAM NAMES IN EARLY BASEBALL .... 891 B. NATIVE AMERICAN TEAMS NAMES IN EARLY PROFESSIONAL BASEBALL 894 C. NATIVE AMERICAN TEAM NAMES IN COLLEGE SPORT 900 V. CONCLUSION 901 I. INTRODUCTION The Native American team name and mascot controversy has dismpted the world of American sports for more than six decades. In the 1940s, the National Congress of American Indians (NCAI) began a campaign against a variety of negative and unfiattering stereotypes of Indians in American culture.' Over time, the campaign began to focus on the use of Native American team names—like Indians and Redskins—and mascots by college and professional sports teams.2 The NCAI's basic argument was that the use of such names, mascots, and logos was offensive and *J. Gordon Hylton is Professor of Law at Marquette University and Visiting Professor of Law at the University of Virginia. He is a graduate of Oberlin College and the University of Virginia Law School and holds a PhD in the History of American Civilization from Harvard. From 1997 to 1999, he was Director ofthe National Sports Law Institute and is the current Chair-Elect ofthe Association of American Law Schools Section on Law and Sport. 1. See Our History, NCAI, http://www.ncai.Org/Our-History.14.0.html (last visited Apr. -

Indian Mascot World Series Tied 1 - 1: Who Will Prevail As Champion? Stacie L

American Indian Law Review Volume 29 | Number 2 1-1-2005 Indian Mascot World Series Tied 1 - 1: Who Will Prevail as Champion? Stacie L. Nicholson Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.ou.edu/ailr Part of the Civil Rights and Discrimination Commons, Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons, Indian and Aboriginal Law Commons, and the Sports Studies Commons Recommended Citation Stacie L. Nicholson, Indian Mascot World Series Tied 1 - 1: Who Will Prevail as Champion?, 29 Am. Indian L. Rev. 341 (2005), https://digitalcommons.law.ou.edu/ailr/vol29/iss2/5 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by University of Oklahoma College of Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in American Indian Law Review by an authorized editor of University of Oklahoma College of Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INDIAN MASCOT WORLD SERIES TIED 1 - 1: WHO WILL PREVAIL AS CHAMPION? Stacie L. Nicholson* Introduction There seems to be a never ending debate over whether the use of the Indian as a team mascot is or is not racist, derogatory, offensive, and/or vulgar (or, as seen by some, all of the aforementioned). What some people view as a harmless representation of a team, others view as a mockery of American Indian culture. Supporters of teams that define themselves by the Indian mascot claim that its use is an honorable one. Opponents argue that the mascot fosters disparagement and insensitivity for a culture that plays an important part of American history. The hostility is mainly channeled to the five professional sports teams that, despite harsh public outcry, continue to be represented by American Indian names and symbols: the Atlanta Braves, Chicago Blackhawks, Cleveland Indians, Kansas City Chiefs, and Washington Redskins. -

Writers Find Their Niche

Spotlight The March 2018 Vol. 67 Issue 5 The Spring Musical: Who, What, Where Page 3: and When The Chief: To Emma Andrus Students involved in the Masqu- nigan, Mason Adams as Angie keep or not to ers program have been working the Ox, Sean Weiland as Joey keep? diligently to memorize countless Biltmore, Zach Zdanowicz as Cal- lines, lyrics, and dances since au- vin, Elizabeth Gonzalez as Sarah ditions for the musical Guys and Brown, Autumn Knierim as Miss Dolls occurred in January. Guys Adelaide, Lizzie Vukovic as Gen- and Dolls is a dynamic comedy eral Matilda B. Cartwright, Katie set in 1930s New York. The plot Cutts as Agatha, Kai Falcone as revolves around the storyline of Allison, Meredith Gardner as Ver- gamblers Nathan Detroit and non, Cassie Urry as Ferguson, and Sky Masterson, who balance tak- countless other students who are a ing risks with money and taking part of the cast and crew. chances with their own respective Senior Meredith Gardner, relationships, which plays into the who will be playing the flirtatious style of this overall quirky and character of Vernon, is looking lively musical. The tale evolved forward to being involved in a pro- Page 3: from short stories written by duction with such a talented group We could not Damon Runyon, made its way of students: “I honestly love mu- to Broadway, was adapted into sicals, so I’m looking forward to playing great music with a great learn without a film, and will be taking center being able to sing, dance, and just bunch of people.” them: a thank stage at Olmsted Falls this spring. -

Bay Rat Road Trips: Take Me out to the Ball Game

Quick, Timely Reads On the Waterfront Bay Rat Road Trips: Take Me Out to the Ball Game By David Frew April 2021 Dr. David Frew, a prolific writer, author, and speaker, grew up on Erie's lower west side as a proud "Bay Rat," joining neighborhood kids playing and marauding along the west bayfront. He has written for years about his beloved Presque Isle and his adventures on the Great Lakes. In this series, the JES Scholar-in-Residence takes note of of life in and around the water. There were two kinds of kids in my neighborhood, Indians fans and Yankees fans. I’m not sure if the differences could be explained with modern DNA scoring. There were no Pittsburgh fans and I suspect that was because of the difficulty of getting there by car from Erie, Pennsylvania. Cleveland was a manageable road trip, even during those pre-Eisenhower Thruway days. But driving to Pittsburgh was way more difficult. That rationalization fails to explain Yankees fans, however, and there were lots of them. Driving to New York City? I did not know anyone who had done it when I was a kid, but lots of us had been to Cleveland Municipal Stadium. Families, including my own, made the trip from time to time, but my Yankee fan buddies had to be satisfied with seeing their team w hen they played the Indians. The 1954 Indians were awesome, and they played at the peak of my own baseball career. The summer of ’54 was the year I finally tried out for and made a Little League team. -

In Age of Trump, Minority Students Vulnerable to Harassment

Vol. 57 No. 05 The Beachcomberwww.bcomber.org Beachwood High School 25100 Fairmount Boulevard Beachwood, Ohio May 27, 2016 In Age of Trump, Minority Students Vulnerable to Harassment “I looked at all my friends and the number of people who support me and respect me; I started focusing on the positive, which gave me more confidence,” Senior Aya Ali said. “Not only that, but my hijab is a constant reminder to me of who I am, no matter what anyone else says.” Photo by Bradford Douglas. course in which xenopho- minder to me of who I am, stated. anti-gay hate speech, that By Dalia Zullig bic language has become no matter what anyone Additionally, the speech does not lose its Online Editor-in-Chief increasingly acceptable. In else says.” Southern Poverty Law constitutional protection Inside This Issue... Ali’s case, she spoke back Ali felt that the stu- Center reported that more just because it is insulting Senior Aya Ali is a on social media to those dents who were talking than two thirds out of or offensive,” he wrote in Muslim-American whose who target her for her eth- about her did not know approximately 2,000 K-12 an email. “For speech to family is from Lebanon. nic origins and religious her as a person, and that teachers surveyed have lose its protection, it must She chooses to wear a beliefs. they hated her because of reported a rise in Mus- be threatening or harass- hijab headscarf. First, in late Feb., Ali’s her religion. lim and black students’ ing -- something that In a public school with friends told her they heard But in the age of Don- concerns with the rise of actually inflicts significant few recognizably Arab prejudiced comments ald Trump, where does Republican presidential discomfort that makes students, she stands out other students were mak- political speech end and candidate Donald Trump. -

Kluber Adds 18Th Win to Cy Young Resume by Jordan

Kluber adds 18th win to Cy Young resume By Jordan Bastian / MLB.com | @MLBastian | September 24th, 2017 + 2 COMMENTS SEATTLE -- Corey Kluber cares about getting a ring, not another plaque. What the ace has been doing for the Indians this year is being driven by his desire to help the club finish what it could not a year ago. He wants to win the World Series and has been pitching like a man possessed by that mission. Kluber continued that pursuit on Sunday at Safeco Field, where he surrendered a two-run homer to Ben Gamel, but nothing else in a 4-2 victory for Cleveland. He has powered baseball's best pitching staff and set the tone for the Tribe's incredible run of 29 wins in 31 games. And, while Kluber shrugs off questions about a possible second American League Cy Young Award, his teammates will do the talking for him. "He's the Cy Young," Jason Kipnis said. "I think he's clearly the Cy Young. That doesn't take anything away from [Red Sox ace] Chris Sale. I think he's clearly the No. 2 and would be the Cy Young any other year that Corey Kluber's not pitching like this." There is still a debate to be had over whether Kluber or Sale -- Boston's overpowering left-hander -- should walk away with the season-end hardware, but the scale may have tilted in the Tribe ace's favor. Dating back to the All-Star break, the Indians have gone 51-18, clinched the AL Central and are now right behind the Dodgers for baseball's best record. -

Examining What Sports Team Names Communicate

WHAT’S IN A NAME: EXAMINING WHAT SPORTS TEAM NAMES COMMUNICATE WHAT’S IN A NAME: EXAMINING WHAT SPORTS TEAM NAMES COMMUNICATE BY BRIDGET LEWIS M.A. THESIS Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Communication in The School of Communication and The Arts at Liberty University Lynchburg, Virginia Adviser: Dr. Marie Mallory i WHAT’S IN A NAME: EXAMINING WHAT SPORTS TEAM NAMES COMMUNICATE Acceptance of Master’s Thesis This Master’s Thesis is accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation from the School of Communication and The Arts At Liberty University. _________________________________ Marie Mallory, Ph.D. Thesis Chair _________________________________ Cecil Kramer, D. Min. Committee Member _________________________________ Bruce Kirk, Ph.D. Committee Member _________________________________ Date ii WHAT’S IN A NAME: EXAMINING WHAT SPORTS TEAM NAMES COMMUNICATE © 2021 Bridget Lewis All Rights Reserved iii WHAT’S IN A NAME: EXAMINING WHAT SPORTS TEAM NAMES COMMUNICATE Abstract For years, there have been controversy and discussion regarding high school, college, and professional sports team name changes. Professional sports teams have gained the most attention regarding team name changes or lack thereof. This study can bring an understanding of the message communicated through the chosen names and logos of sports teams as well as the effects of financial, political, and fan base changes on team name changes in the sports industry. Extensive research is provided to show the previous content on the topic as well as areas where further research would be beneficial. This includes previous and current sport name changes, name history, political, media, and financial influence, Native American involvement, relatable communication theories, and reactions. -

The Indians' Chief Problem: Chief Wahoo As State Sponsored Discrimination and a Disparaging Mark

Cleveland State Law Review Volume 46 Issue 2 Article 3 1998 The Indians' Chief Problem: Chief Wahoo as State Sponsored Discrimination and a Disparaging Mark Jack Achiezer Guggenheim Sidley & Austin Follow this and additional works at: https://engagedscholarship.csuohio.edu/clevstlrev Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons, and the State and Local Government Law Commons How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! Recommended Citation Jack Achiezer Guggenheim, The Indians' Chief Problem: Chief Wahoo as State Sponsored Discrimination and a Disparaging Mark, 46 Clev. St. L. Rev. 211 (1998) available at https://engagedscholarship.csuohio.edu/clevstlrev/vol46/iss2/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at EngagedScholarship@CSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Cleveland State Law Review by an authorized editor of EngagedScholarship@CSU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE INDIANS' CHIEF PROBLEM: CHIEF WAHOO AS STATE SPONSORED DISCRIMINATION AND A DISPARAGING MARK ]ACK ACI-IIEZER GUGGENHEIMl I. INTRODUCTION .................................... 212 II. THE CLEVELAND INDIANS ............................ 213 A. History of the Cleveland Indians .................. 213 B. History of Chief Wahoo ......................... 214 III. CHIEF WAHOO AS STATE SPONSORED DISCRIMINATION ....... 215 A. Chief Wahoo as State Action ..................... 215 B. Equal Protection Under the Fourteenth Amendment .................................. 221 C. Chief Wahoo as a Violation of the Fourteenth Amendment .................................. 222 D. Chief Wahoo as Racist Speech .................... 223 1. Theory of First Amendment Prohibiting Government Endorsed Racist Speech ......... 224 2. The Theory as Applied to Chief Wahoo ....... 225 E. Similar Prior Challenge Failed ................... 226 IV. -

Implicit Religion and the Highly-Identified Sports Fan: an Ethnography of Cleveland Sports Fandom

IMPLICIT RELIGION AND THE HIGHLY-IDENTIFIED SPORTS FAN: AN ETHNOGRAPHY OF CLEVELAND SPORTS FANDOM Edward T. Uszynski A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2013 Committee: Dr. Michael Butterworth, Advisor Dr. Kara Joyner Graduate Faculty Representative Dr. Bruce Edwards Dr. Vikki Krane ii ABSTRACT Michael Butterworth, Advisor Scholarly writing on the conflation of “sport as a religion” regularly concentrates on the historical and institutional parallels with the religious dimensions of sport, focusing on ritual, community, sacred space, and other categories more traditionally associated with “religious” life. Instead, this study redirects focus toward the neo-religious nature of modern spirituality; that is, the fulfillment of Thomas Luckmann’s prediction that a significant aspect of modern spirituality would concern the need to construct a “self”the constantly shifting work of forming personal identity and enhancing self understanding. As such, internal commitments and intense devotion may perform as a de facto “invisible religion” in the lives of people. As popular culture provides useful texts toward satisfying this ongoing work, professional sports can act as a conduit of both personal and collective self understanding for “highly identified fans,” subsequently operating as an invisible religion within their lives. This study investigates the nature of fandom among a sample of Cleveland professional sports -

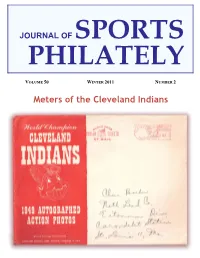

Meters of the Cleveland Indians TABLE of CONTENTS

JOURNAL OF SPORTS PHILATELY VOLUME 50 WINTER 2011 NUMBER 2 Meters of the Cleveland Indians TABLE OF CONTENTS President's Message Mark Maestrone 1 China Post - Advertising Postal Stationery Bob Farley 3 for the XXIX Olympic Games, Beijing 2008 Meters of the Cleveland Indians Norman Rushefsky 8 Program of the 1944 Olympics at Oflag IID, Roman Sobus 12 Gross Born (Part Two) Registered Mail of the 1928 Amsterdam Laurentz Jonker 17 Olympic Games: An Update Celebrating 75 Years of the Olympic Torch Relay Thomas Lippert 20 The Women’s Olympics Fdn. Hellenic World 23 Building Your Olympic Games Collection Mark Maestrone 26 The Mystery of the 1988 Olympic Lottery Card Bob Farley 27 Olympic Collectibles Stathis Douramakos 28 SPI Annual Financial Statement: FY2011 & 2010 Andrew Urushima 30 Reviews of Periodicals Mark Maestrone 31 News of Our Members Mark Maestrone 32 www.sportstamps.org New Stamp Issues John La Porta 34 Commemorative Stamp Cancels Mark Maestrone 36 2008 BEIJING SPORTS PHILATELISTS INTERNATIONAL OLYMPIC GAMES President: Mark C. Maestrone, 2824 Curie Place, San Diego, CA 92122 3 Vice-President: Charles V. Covell, Jr., 207 NE 9th Ave., Gainesville, FL 32601 Secretary-Treasurer: Andrew Urushima, 1510 Los Altos Dr., Burlingame, CA 94010 Directors: Norman F. Jacobs, Jr., 2712 N. Decatur Rd., Decatur, GA 30033 John La Porta, P.O. Box 98, Orland Park, IL 60462 Dale Lilljedahl, 4044 Williamsburg Rd., Dallas, TX 75220 Patricia Ann Loehr, 2603 Wauwatosa Ave., Apt 2, Wauwatosa, WI 53213 Norman Rushefsky, 9215 Colesville Road, Silver Spring, MD 20910 Robert J. Wilcock, 24 Hamilton Cres., Brentwood, Essex, CM14 5ES, England Auction Manager: Glenn Estus, PO Box 451, Westport, NY 12993 Membership (Temporary): Mark C. -

Negotiating American Indian Identity in the Land of Wahoo

NEGOTIATING AMERICAN INDIAN IDENTITY IN THE LAND OF WAHOO A dissertation submitted to the Kent State University College of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Michelle R. Jacobs August 2012 Dissertation written by Michelle R. Jacobs B.A., University of Akron, 2002 M.A., Kent State University, 2007 Ph.D., Kent State University, 2012 Approved by ______________________________, Co-Chair, Doctoral Dissertation Committee (Clare L. Stacey) ______________________________, Co-Chair, Doctoral Dissertation Committee (Kathryn M. Feltey) ______________________________, Members, Doctoral Dissertation Committee (James V. Fenelon) ______________________________, (David H. Kaplan) ______________________________, (Tiffany Taylor) Accepted by ______________________________, Chair, Department of Sociology (Richard T. Serpe) ______________________________, Dean, College of Arts and Sciences (John R. D. Stalvey) ii TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ...................................................................................................ix INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................. 1 LITERATURE REVIEW ...................................................................................................... 8 Racial Formations ..................................................................................................... 8 Race as an Accomplishment .........................................................................