CHAPTER 3 KOALA and OTHER MATTERS – the 1910S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Linda Scott for Sydney Strong, Local, Committed

The South Sydney Herald is available online: www.southsydneyherald.com.au FREE printed edition every month to 21,000+ regular readers. VOLUME ONE NUMBER FORTY-NINE MAR’07 CIRCULATION 21,000 ALEXANDRIA BEACONSFIELD CHIPPENDALE DARLINGTON ERSKINEVILLE KINGS CROSS NEWTOWN REDFERN SURRY HILLS WATERLOO WOOLLOOMOOLOO ZETLAND RESTORE HUMAN RIGHTS BRING DAVID HICKS HOME New South Wales decides PROTEST AT 264 PITT STREET, CITY The South Sydney Herald gives you, as a two page insert, SUNDAY MARCH 25 ✓ information you need to know about your voting electorates. PAGES 8 & 13 More on PAGE 15 Water and housing: Labor and Greens Frank hits a high note - good news for live music? go toe to toe John Wardle Bill Birtles and Trevor Davies The live music scene in NSW is set to receive a new and much fairer regu- Heffron Labor incumbent Kristina latory system, after Planning Minister Keneally has denied that the State Frank Sartor and the Iemma Govern- government’s promised desalination ment implemented amendments to plant will cause road closures and the Local Government Act including extensive roadwork in Erskineville. a streamlined process to regulate Claims that the $1.9 billion desalina- entertainment in NSW and bring us tion plant at Kurnell will cause two more into line with other states. years of roadworks across Sydney’s Passed in the last week of Parlia- southern suburbs were first made by ment in November 2006, these the Daily Telegraph in February. reforms are “long overdue, and State government plans revealed extremely good news for the live that the 9 km pipeline needed to music industry” says Planning connect the city water tunnel with the Minister Frank Sartor. -

The Large Professional Service Firm: a New Force in the Regulative Bargain

21 UNSW Law Journal Volume 40(1) 11 THE LARGE PROFESSIONAL SERVICE FIRM: A NEW FORCE IN THE REGULATIVE BARGAIN JUSTINE ROGERS, DIMITY KINGSFORD SMITH AND JOHN CHELLEW I INTRODUCTION This article charts the rise of a new force in the regulative bargain:1 the large organisation or ‘professional service firm’. The ‘regulative bargain’ refers to the bargain, both theoretical and real, 2 between the professions and the state, on behalf of society. Increasingly, these parties actively negotiate the exchange of professional benefits and responsibilities, and how, where and for what purpose these will be allocated and enforced. This bargain is shaped too by the political climate and culture, and the access to the networks within which this agreement takes place. 3 The classic bargain is the grant of self-regulation and other Lecturer, UNSW Law, MSc (Oxon), DPhil (Oxon). Correspondence to Dr Justine Rogers <[email protected]>. Professor and Director of the Centre for Law, Markets and Regulation (‘CLMR’), UNSW Sydney, LLM (London School of Economics) LLB (Sydney) BA (Sydney). Senior Research Fellow, UNSW Law. LLB (Monash), BA (Monash). Member of the CLMR, UNSW Law. The authors acknowledge the support of the Australian Research Council and the Professional Standards Councils for this work. They are also grateful for the support of professional partners to the grant, law firms Allens and Corrs Chambers Westgarth. The authors also acknowledge the support of the CLMR at UNSW Law, particularly the work of CLMR interns, Deborah Hartstein and Jason Zhang. They are also grateful for the considered comments of two anonymous referees. -

Publications

treatment plants across NSW can be “Sewage Treatment Plants need no approved without an assessment of Environmental Impact Statement ”, off-site impacts. BRAID and environmental groups across the state are says Sartor appalled by this political intervention. The old regulation didn’t In November 2006, BRAID won a landmark case when the prevent development, it merely balanced it with appropriate Court of Appeal determined that an amendment in 2000 to the environmental protection. This has now been swept aside by a Environmental Planning & Assessment Regulation meant that stroke of the Minister’s pen, making a mockery of the legal on-site sewage treatment plants are “designated development”, process that BRAID faithfully followed to get their result. thus requiring an Environmental Impact Statement. This judgement quashed the approval by the Land & Environment Court of the Parklands development in Blackheath, because it BRAID Fundraiser Cancelled was assessed without an EIS. BRAID has cancelled its May 12 fundraising event But on March 1, 2007 the Planning Minister reversed the (advertised in the March ‘ Hut News’ ), in favour of a big BASH regulation, effectively overturning the Court’s decision. The in June with all BMCS members invited. Watch the May issue new amendment states that sewage treatment plants that are of Hut News for details. “ancillary” to another purpose, such as a resort, are not Virginia King, designated development. Not only does this pave the way for BRAID approval of the Parklands development, it means that sewage (Blackheath Residents Against Improper Development) WHAT NOW FOR THE ENVIRONMENT? Four more years of hard Labor? ——— or will the rere----electedelected NSW Government turn over a new leaf? On March 24 NSW voters returned the Iemma Government for another four years. -

The Devil's Triangle

THE DEVIL’S TRIANGLE Civil liberties and the relationship between the law, the media and the parliament Bob Debus Attorney General of New South Wales 2000-2007 Sir Frank Kitto Lecture, University of New England, November 23rd 2012. This Lecture commemorates the great figure in Australian legal history Justice Sir Frank Kitto, who served on The High Court of Australia from 1950 to 1970 and was thereupon elected Chancellor of this University. As long ago as 1998 Justice Michael Kirby used this lecture to describe not only Sir Frank’s contribution to the law but his high integrity, demonstrated for instance, in the unequivocal judgment in which he joined the majority in Communist the seminal decision to strike down the Menzies Government’s Party Dissolution Act 1950. It was the beginning of the Cold War but Kitto was immune to the politics of the situation: “…it may have been thought (although never said in those more graceful days) that Justice Kitto was a ‘capital C conservative’. His skills were in the black letter law… He had just succeeded in a substantial brief for the banks in striking down the nationalisation scheme of the former Labor Government. Yet in less than a year, he performed his function as a judge of our highest court, in accordance with his understanding of the law and the Constitution precisely and only as his learning and 1 conscience dictated.” In the period 1976 to 1982 he was inaugural Chairman of The Australian Press Council. I venture to believe that he may have grudgingly approved the national defamation law finally achieved by the Commonwealth and State Attorneys General in 2005 after years of difficult negotiation. -

FRI 005 Newsletter

Friends of the ABC (NSW) Inc. quarterly newsletter April 2009 Vol 17, No.1 update friends of the abc they use Question Time to pursue the The 2009 Federal Budget issue. We acknowledge the work of FABC ACT in keeping the ABC high on the political agenda, and several FABC will make or branches have ensured that their local members are active on the case - see letters from Bob Debus (Blue Mountains) and Julie Owens break the ABC (Parramatta) elsewhere in Update. We thank Jill Greenwell (ACT FABC) for providing us with a Guide for A word from the NSW President - Mal Hewitt Prospective Lobbyists. We also report elsewhere on the The Budget to be productions. Four years ago, a KPMG energetic attempts by SkyNews to take handed down by the audit, initiated by the Howard over the Australian Network TV Rudd Government in government but never released, Service, through which the ABC May is of critical recommended an immediate 10% currently broadcasts into Asia and the importance to the ABC, increase in funding if the ABC was to Pacific, supported by funding from the and will determine be able to maintain existing levels of Federal Department of Foreign Affairs whether it retains its production. position as a world-renowned public broadcaster, free of commercial and THE COST OF KEEPING PACE political influence, or continues an WITH THE WORLD already discernible slide into The ABC has very effectively mediocrity. ABC funding for the next embraced the digital revolution in inside three years is now in the hands of broadcasting, and leads the world in Minister Conroy announces new Treasurer Swan, Finance Minister podcasting and vodcasting. -

The New South Wales Parliament Under Siege

‘Build your House of Parliament upon the River’: The New South Wales Parliament under siege Gareth Griffith and Mark Swinson * You must build your House of Parliament upon the river . the populace cannot exact their demands by sitting down round you. — The Duke of Wellington This piece of advice is attributed to the Duke of Wellington, a man who knew about such things as pickets and blockades, but also about Parliament and its ways. On Tuesday 19 June 2001, a part of the populace associated with the trade union movement, determined to have its demands satisfied, massed round the New South Wales Parliament House. For those who do not know it, the New South Wales Parliament is not built on a river, or a harbour for that matter, but on the crest of a modest rise, fronted by Macquarie Street to the west and, at the rear, by Hospital Road and beyond that by a spacious open area called the Domain. To the north side is the State Library building; to the other, Sydney Hospital. At its height, in the early afternoon of 19 June, the Parliament was surrounded by a demonstration estimated to be 1,000 strong. The Premier called it a ‘blockade’. 1 Unionists called it a ‘picket’. 2 Some press reports referred to it as a ‘riot’. 3 * Gareth Griffith is a Senior Research Officer with the New South Wales Parliamentary Library; Mark Swinson is Deputy Clerk of the Legislative Assembly, Parliament of New South Wales. 1 L. McIIveen, ‘House is shut down by union blockade’, The Sydney Morning Herald , 20 June 2001; G. -

NSW Election 2007

Parliament of Australia Department of Parliamentary Services Parliamentary Library RESEARCH NOTE Information, analysis and advice for the Parliament 25 May 2007, no. 19, 2006–07, ISSN 1449-8456 New South Wales election 2007 Introduction use Sydney’s Cross-City tunnel, riots in Redfern, Cronulla and Dubbo, rail problems flowing from the Waterfall and Nine days before the NSW election of 24 March 2007, an Glenbrook accidents, increasingly clogged Sydney roads, accident on the Sydney Harbour Bridge left an estimated and the ailing state economy. As a critic noted just five 35,000 rush hour train commuters stranded for many weeks from polling day: ‘It is hard to make a case that this hours. It was the latest in a number of serious transport is a government that deserves to be re-elected’.4 problems in the capital. The Government had also been embarrassed by various of Australian state and territory election arguments revolve its ministers. In October 2006 Carl Scully resigned his around the issue of whether or not services are provided— Police portfolio, admitting that he had twice lied to and perform adequately. During 2005–2006, Newspoll had Parliament in relation to a police report into the Cronulla Labor trailing the Coalition parties, pointing to community riots of 11 December 2005. Soon after, Kerry Hickey unhappiness in a state with a host of government service (Local Government) admitted to four speeding charges, delivery problems. Despite this, the Labor Government including three with his official car, and Milton won a comfortable electoral victory, with the issue of Orkopoulos (Aboriginal Affairs) was charged with thirty poorly-performing State services clearly not persuading drug and child sex offences. -

Notice Paper

2004-05 THE PARLIAMENT OF THE COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA THE SENATE NOTICE PAPER No. 50 TUESDAY, 11 OCTOBER 2005 The Senate meets at 12.30 pm Contents Business of the Senate Notice of Motion .......................................................................................................2 Government Business Notice of Motion .......................................................................................................2 Orders of the Day ......................................................................................................2 Orders of the Day relating to Committee Reports and Government Responses and Auditor-General’s Reports..............................................................................................5 General Business Notices of Motion......................................................................................................6 Orders of the Day relating to Government Documents..............................................12 Orders of the Day ....................................................................................................12 Business for Future Consideration.................................................................................17 Bills Referred to Committees........................................................................................24 Bills Discharged, Laid Aside or Negatived....................................................................25 Questions on Notice .....................................................................................................25 -

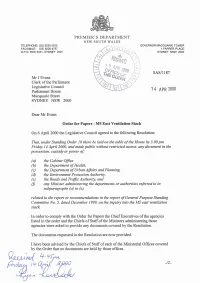

M5 East Ventilation Stack That, Under Standing Order 18 There Be Laid On

PREMIER'S DEPARTMENT NEW SOUTH WALES TELEPHONE: 102) 9228 5255 GOVERNOR MACQUARIE TOWER FACSIMILE: ioz) 9228 4757 1 FARRER PLACE G.P.O. BOX 5341, SYDNEY 2001 SYDNEY NSW 2000 SASl1187 Mr J Evans Clerk of the Parliament Legislative Council Parliament House Macquarie Street SYDNEY NSW 2000 Dear Mr Evans Order for Papers - M5 East Ventilation Stack On 6 April 2000 the Legislative Council agreed to the following Resolution: That, under Standing Order 18 there be laid on the table of the House by 5.00pm Friday 14 April 2000, and made public without restricted access, any document in the possession, custody or power of (a) the Cabinet Ofice (b) the Department of Health, (c) the Department of Urban Affairs and Planning, (4 the Environment Protection Authority, (e) the Roads and Trafic Authority, and fl any Minister administering the departments or authorities referred to in subparagraphs (a) to (e), related to the report or recommendations in the report of General Purpose Standing Committee No. 5, dated December 1999, on the inquiry into the M5 east ventilation stack In order to comply with the Order for Papers the Chief Executives of the agencies listed in the order and the Chiefs of Staff of the Ministers administering those agencies were asked to provide any documents covered by the Resolution. The documents requested in the Resolution are now provided. I have been advised by the Chiefs of Staff of each of the Ministerial Offices covered by the Order that no documents are held by those offices. Certification by each of the Chief Executive Officers indicating that to the best of their knowledge all documents held by their organisation and covered by the Resolution are attached as Annexure A. -

Annual Report 2004

2004 2005 ANNUAL REPORT MUSEUM OF APPLIED ARTS & SCIENCES INCORPORATING THE POWERHOUSE MUSEUM & SYDNEY OBSERVATORY The Hon Bob Debus MP Attorney General, Minister for the Environment and Minister for the Arts Parliament House Sydney NSW 2000 Dear Minister On behalf of the Board of Trustees and in accordance with the Annual Reports (Statutory Bodies) Act 1984 and the Public Finance and Audit Act 1983, we submit for presentation to Parliament the annual report of the Museum of Applied Arts and Sciences for the year ending 30 June 2005. Yours sincerely Dr Nicholas G Pappas Dr Anne Summers AO President Deputy President ISSN 0312-6013 © Trustees of the Museum of Applied Arts and Sciences 2005. Compiled by Mark Daly, MAAS. Design and production by designplat4m 02 9299 0429 Print run: 600. External costs: $14,320 Available at www.powerhousemuseum.com Contemporary photography by MAAS photography staff: Sotha Bourn, Geoff Friend, Marinco Kojdanovski, Jean-Francois Lanzarone and Sue Stafford (unless otherwise credited). Historical photos from Museum archives. Contents 02 President’s Foreword 03 Director’s Report 04 Mission and structure 05 Organisation chart 06 Progress against Strategic Plan 07 Goals 2005-06 08 Museum honours th 09 125 anniversary celebrations 10 Highlights of 2004-05 11 The Powerhouse Foundation 11 Evaluating our audiences, exhibitions and programs 12 Exhibition program 13 Travelling exhibitions 13 Public and education programs tm 15 SoundHouse and VectorLab 15 Sydney Observatory 16 Indigenous culture 16 Regional services 17 Migration -

“The Things Which Must Be Done…” Aboriginal Incarceration: the Urgent Need for Aboriginal Community Solutions

PERSPECTIVES “The Things Which Must Be Done…” Aboriginal Incarceration: the urgent need for Aboriginal community solutions. The Honourable Bob Debus AM August 2016 1 15 Authored by: Whitlam Institute The Honourable Bob Debus AM Bob Debus was a Member of the NSW Parliament from 1981 to 1988 and again from 1995 to 2007. He was a Member of Perspectives Federal Parliament from 2007 to 2010. He has held numerous portfolios in NSW including Minister for Environment (1999- Perspectives is a series of essays from the Whitlam 2007), Attorney General (2000-2007), Minister for Corrective Institute. Perspectives offers respected public intellectuals Services (1995-2001), Minister for Emergency Services (1995- an opportunity to canvass ideas and to put their views 2003) and Minister for Arts (2005-2007). From 2007 to 2009 forward on the policies that would shape a better, fairer he was Minister for Home Affairs in the Federal Parliament. Australia. The series is designed to encourage creative, even bold, thinking and occasionally new ways of looking Mr Debus was the National Director of the Australian Freedom at the challenges of the 21st Century in the hope that the From Hunger Campaign from 1989 to 1994. He is a former enthusiasm and insights of these authors sparks further lawyer, publisher and ABC radio broadcaster. thought and debate among policy makers and across the community. He is a Visiting Professorial Fellow, Faculty of Law at the University of New South Wales. About the Whitlam Institute The Whitlam Institute within Western Sydney University at Parramatta commemorates the life and work of Gough Whitlam and pursues the causes he championed. -

13-Clune Nsw Election 07

‘Morris’ Minor Miracle’: The March 2007 NSW Election ∗ David Clune Carr Crashes Bob Carr was triumphantly re-elected in March 2003. Labor won 56.20% of the two-party preferred vote and 55 of the 93 electorates. The Government consolidated its hold on many of its marginal seats. The Opposition failed to regain any of the ground lost in 1999. Carr radically reconstructed his Ministry and began to implement his third term agenda. The Government looked unassailable. Then it all began to fall apart. In December 2003, a report by the Health Care Complaints Commission into allegations by whistleblower nurses confirmed alarming failings in relation to care and treatment of patients at Camden and Campbelltown hospitals. Up to 19 patients died unnecessarily between 1999 and 2003. Chronic underfunding and staff shortages had led to this disastrous situation. The revelations about Camden and Campbelltown were followed by a flood of similar allegations about other hospitals. 1 The confidence of the citizens of NSW in their health care system, and the Government’s ability to manage it, was severely shaken. In early 2004, there was a drastic decline in the quality of Sydney’s train service. The railway network’s ageing infrastructure had been causing problems for some time. The immediate crisis was triggered by a shortage of drivers, the medical retirement of a number of drivers as a result of strict new fitness tests, and the ∗ Manager, Research Service, NSW Parliamentary Library and Adjunct Lecturer in Government, University of Sydney. The opinions expressed are those of the author not the NSW Parliamentary Library.