China Media Bulletin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The CPC Its Mission and Contributions

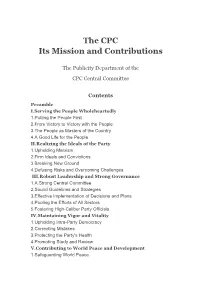

The CPC Its Mission and Contributions The Publicity Department of the CPC Central Committee Contents Preamble I.Serving the People Wholeheartedly 1.Putting the People First 2.From Victory to Victory with the People 3.The People as Masters of the Country 4.A Good Life for the People II.Realizing the Ideals of the Party 1.Upholding Marxism 2.Firm Ideals and Convictions 3.Breaking New Ground 4.Defusing Risks and Overcoming Challenges III.Robust Leadership and Strong Governance 1.A Strong Central Committee 2.Sound Guidelines and Strategies 3.Effective Implementation of Decisions and Plans 4.Pooling the Efforts of All Sectors 5.Fostering High-Caliber Party Officials IV.Maintaining Vigor and Vitality 1.Upholding Intra-Party Democracy 2.Correcting Mistakes 3.Protecting the Party's Health 4.Promoting Study and Review V.Contributing to World Peace and Development 1.Safeguarding World Peace 2.Pursuing Common Development 3.Following the Path of Peaceful Development 4.Building a Global Community of Shared Future Conclusion Preamble The Communist Party of China (CPC), founded in 1921, has just celebrated its centenary. These hundred years have been a period of dramatic change – enormous productive forces unleashed, social transformation unprecedented in scale, and huge advances in human civilization. On the other hand, humanity has been afflicted by devastating wars and suffering. These hundred years have also witnessed profound and transformative change in China. And it is the CPC that has made this change possible. The Chinese nation is a great nation. With a history dating back more than 5,000 years, China has made an indelible contribution to human civilization. -

28. Rights Defense and New Citizen's Movement

JOBNAME: EE10 Biddulph PAGE: 1 SESS: 3 OUTPUT: Fri May 10 14:09:18 2019 28. Rights defense and new citizen’s movement Teng Biao 28.1 THE RISE OF THE RIGHTS DEFENSE MOVEMENT The ‘Rights Defense Movement’ (weiquan yundong) emerged in the early 2000s as a new focus of the Chinese democracy movement, succeeding the Xidan Democracy Wall movement of the late 1970s and the Tiananmen Democracy movement of 1989. It is a social movement ‘involving all social strata throughout the country and covering every aspect of human rights’ (Feng Chongyi 2009, p. 151), one in which Chinese citizens assert their constitutional and legal rights through lawful means and within the legal framework of the country. As Benney (2013, p. 12) notes, the term ‘weiquan’is used by different people to refer to different things in different contexts. Although Chinese rights defense lawyers have played a key role in defining and providing leadership to this emerging weiquan movement (Carnes 2006; Pils 2016), numerous non-lawyer activists and organizations are also involved in it. The discourse and activities of ‘rights defense’ (weiquan) originated in the 1990s, when some citizens began using the law to defend consumer rights. The 1990s also saw the early development of rural anti-tax movements, labor rights campaigns, women’s rights campaigns and an environmental movement. However, in a narrow sense as well as from a historical perspective, the term weiquan movement only refers to the rights campaigns that emerged after the Sun Zhigang incident in 2003 (Zhu Han 2016, pp. 55, 60). The Sun Zhigang incident not only marks the beginning of the rights defense movement; it also can be seen as one of its few successes. -

Tiktok and Wechat Curating and Controlling Global Information Flows

TikTok and WeChat Curating and controlling global information flows Fergus Ryan, Audrey Fritz and Daria Impiombato Policy Brief Report No. 37/2020 About the authors Fergus Ryan is an Analyst working with the International Cyber Policy Centre at ASPI. Audrey Fritz is a Researcher working with the International Cyber Policy Centre at ASPI. Daria Impiombato is an Intern working with the International Cyber Policy Centre at ASPI. Acknowledgements We would like to thank Danielle Cave and Fergus Hanson for their work on this project. We would also like to thank Michael Shoebridge, Dr Samantha Hoffman, Jordan Schneider, Elliott Zaagman and Greg Walton for their feedback on this report as well as Ed Moore for his invaluable help and advice. We would also like to thank anonymous technically-focused peer reviewers. This project began in 2019 and in early 2020 ASPI was awarded a research grant from the US State Department for US$250k, which was used towards this report. The work of ICPC would not be possible without the financial support of our partners and sponsors across governments, industry and civil society. What is ASPI? The Australian Strategic Policy Institute was formed in 2001 as an independent, non-partisan think tank. Its core aim is to provide the Australian Government with fresh ideas on Australia’s defence, security and strategic policy choices. ASPI is responsible for informing the public on a range of strategic issues, generating new thinking for government and harnessing strategic thinking internationally. ASPI’s sources of funding are identified in our Annual Report, online at www.aspi.org.au and in the acknowledgements section of individual publications. -

Who Benefits? China-Africa Relations Through the Prism of Culture

3/2008 3/20083/2008 3/2008 Call for Papers Call for Papers China aktuell – Journal of Current Chinese Affairs is an inter- ChinaCall aktuellnationally for – Papers Journal refereed of academicCurrent Chinesejournal published Affairs isby anthe inter-GIGA Institute nationally ofrefereed Asian Studies,academic Hamburg. journal published The quar terlyby the journal GIGA focuses Institute on current 3/2008 China aktuell – Journal of Current Chinese Affairs is an inter- 3/2008 3/2008 3/2008 of Asiannationally Studies,developments refereed Hamburg. inacademic Greater The quar journalChina.terly publishedjournalIt has a focuses circulation by the on GIGA currentof 1,200 Institute copies, developmentsof Asianmaking Studies,in Greaterit one Hamburg. of China. the world’s ItThe has quar amost circulationterly widely journal ofdistributed focuses1,200 copies, onperiodicals current on 3/2008 makingdevelopments it Asianone of affairs,the in world’sGreater and mostChina.reaches widely It hasa distributed broada circulation readership periodicals of 1,200 in oncopies,academia, Asianmaking affairs,administration it oneand ofreaches the and world’s businessa broadmost circles. widelyreadership distributedArticles in shouldacademia, periodicals be written on in administrationAsianGerman affairs, and or businessEnglishand reaches and circles. submitted a Articlesbroad exclusively shouldreadership tobe this writtenin publication. academia, in German or English and submitted exclusively to this publication. administrationChina aktuell and is businessdevoted -

11.13.2020 CHINA | Concerns Remain for Detained Activist

11.13.2020 CHINA | Concerns Remain for Detained Activist CSW has reiterated calls for the release of detained Chinese human rights defender Zhang Zhan, amid continued concerns for her health and well-being. Nov. 14 will mark six months since Zhang, a Christian and former lawyer, was detained by Chinese authorities. Zhang had travelled to Wuhan, the epicenter of the COVID-19 outbreak, in early February, from where she posted videos and articles about the COVID-19 outbreak on Twitter and YouTube, both of which are blocked in China, and other social media platforms. She was taken away from her hotel room in Wuhan by Shanghai police on May 14 and has been detained the Pudong District Detention Centre in Shanghai ever since. In October, CSW reported that Zhang had been on a hunger strike in protest of her detention since the beginning of summer, with staff at the detention center force-feeding her as she refused to eat or drink anything. Recent reports indicate that Zhang remains on hunger strike, and there are serious fears for health and wellbeing. Additionally, CSW sources report that Zhang’s lawyer Wen Yu, who was only able to meet with her in September, is no longer responsible for her case. The reasons for this are unclear. CSW’s Founder President Mervyn Thomas said, “Once again CSW calls for the immediate and unconditional release of Zhang Zhan, who has now been detained for six months solely for reporting information of public concern. We are deeply concerned for Zhang’s health, and at reports that her lawyer has left her case. -

Speech at a Ceremony Marking the Centenary of the Communist Party of China July 1, 2021

Speech at a Ceremony Marking the Centenary of the Communist Party of China July 1, 2021 Xi Jinping Comrades and friends, Today, the first of July, is a great and solemn day in the history of both the Communist Party of China (CPC) and the Chinese nation. We gather here to join all Party members and Chinese people of all ethnic groups around the country in celebrating the centenary of the Party, looking back on the glorious journey the Party has traveled over 100 years of struggle, and looking ahead to the bright prospects for the rejuvenation of the Chinese nation. To begin, let me extend warm congratulations to all Party members on behalf of the CPC Central Committee. On this special occasion, it is my honor to declare on behalf of the Party and the people that through the continued efforts of the whole Party and the entire nation, we have realized the first centenary goal of building a moderately prosperous society in all respects. This means that we have brought about a historic resolution to the problem of absolute poverty in China, and we are now marching in confident strides toward the second centenary goal of building China into a great modern socialist country in all respects. This is a great and glorious accomplishment for the Chinese nation, for the Chinese people, and for the Communist Party of China! Comrades and friends, The Chinese nation is a great nation. With a history of more than 5,000 years, China has made indelible contributions to the progress of human civilization. -

The Catholic Church in Contemporary China: How Does the New Regulation on Religious Affairs Influence the Catholic Church?

religions Article The Catholic Church in Contemporary China: How Does the New Regulation on Religious Affairs Influence the Catholic Church? Magdaléna Masláková * and Anežka Satorová China Studies Seminar, Faculty of Arts, Masaryk University, 60200 Brno, Czech Republic * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 13 June 2019; Accepted: 19 July 2019; Published: 23 July 2019 Abstract: The Chinese government has regulated all religious activity in the public domain for many years. The state has generally considered religious groups as representing a potential challenge to the authority of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), which sees one of its basic roles as making sure religion neither interferes with the state’s exercise of power nor harms its citizens. A revised Regulation on Religious Affairs (Zongjiao shiwu tiaoli 宗Y事¡a例) took effect in 2018, updating the regulation of 2005. This paper aims to introduce and examine the content of the regulation, especially how it differs from its predecessor and how the changes are likely to affect religious groups in China. The Catholic church in China has historical links to the worldwide Catholic church, so articles in the new regulation which seek to curb foreign influence on Chinese religious groups may have more of an effect on Chinese Catholics than on other groups. The paper addresses two main questions: How dose the new regulation affect the Catholic church and what strategies are employed by the Catholic church in order to comply with the regulation? The research is based on textual analysis of the relevant legal documents and on field research conducted in the People Republic of China (PRC). -

Confronting the Crisis of Global Governance

CONFRONTING THE CRISIS OF GLOBAL GOVERNANCE Executive Summary Report of the Commission on GLOBAL SECURITY, JUSTICE & GOVERNANCE June 2015 The Report of the Commission on Global Security, Justice & Governance is supported by The Hague Institute for Global Justice and the Stimson Center. About The Hague Institute for Global Justice The Hague Institute for Global Justice is an independent, nonpartisan organization established to conduct interdisciplinary policy-relevant research, develop practitioner tools, and convene experts, practitioners, and policymakers to facilitate knowledge sharing. Through this work the Institute aims to contribute to, and further strengthen, the global framework for preventing and resolving conflict and promoting international peace. The Hague Institute for Global Justice, or simply The Hague Institute, was established in 2011 by the city of The Hague, key Hague-based organizations, and with support from the Dutch government. Located in the city that has been a symbol of peace and justice for over a century, The Hague Institute is positioned uniquely to address issues at the intersection of peace, security, and justice. About Stimson The Stimson Center is a nonprofit and nonpartisan think tank that finds pragmatic solutions to global security challenges. In 2014, Stimson celebrated twenty-five years of pragmatic research and policy analysis to reduce nuclear, environmental, and other transnational threats to global, regional, and national security; enhance policymakers’ and public understanding of the changing global security agenda; engage civil society and industry in problem-solving to help fill gaps in existing governance structures; and strengthen institutions and processes for a more peaceful world. The MacArthur Foundation recognized Stimson in 2013 with its Award for Creative and Effective Institutions. -

China's Response to the Coronavirus Pandemic: Fighting Two Enemies

China’s Response to the Coronavirus Pandemic: Fighting Two Enemies Eva Pils 2020-05-25T13:03:57 Autocratic crisis management as model? In many countries around the world, the coronavirus outbreak may have increased the risk of democratic retrogression, as a result of proto-autocratic emergency responses to the public health crises unfolding in their societies. In China, autocracy is already well-entrenched. From the perspective of the Chinese Communist Party, indeed, its handling of the pandemic has been a global model teaching us that China’s governance system is better suited to deal with crises than liberal democracies with their complex constraints on emergency powers. But the reality of China’s coronavirus experience raises distinctive legal-political concerns. The Party has used its vast and concentrated power to fight not only the virus, but also domestic critics of its response, including medical professionals, journalists, human rights activists, a constitutional law professor, and citizens simply speaking up via the social media because they were engaged, or enraged, or both. The fight against one of these ‘enemies’, inevitably, has affected that against the other. To understand this correlation, it is necessary to recall how China’s public health emergency unfolded. It is now believed that the global coronavirus crisis started in November 2019, when the first infections were recorded in Wuhan, an 11 million city in Hubei Province, central China. As the dangerous nature of the new disease unfolded in the following weeks, local and central authorities came under rising pressure to acknowledge the problem; but instead, they suppressed its discussion by healthcare workers even after taking some initial measures to contain and study the outbreak. -

Artificial Intelligence, China, Russia, and the Global Order Technological, Political, Global, and Creative Perspectives

AIR UNIVERSITY LIBRARY AIR UNIVERSITY PRESS Artificial Intelligence, China, Russia, and the Global Order Technological, Political, Global, and Creative Perspectives Shazeda Ahmed (UC Berkeley), Natasha E. Bajema (NDU), Samuel Bendett (CNA), Benjamin Angel Chang (MIT), Rogier Creemers (Leiden University), Chris C. Demchak (Naval War College), Sarah W. Denton (George Mason University), Jeffrey Ding (Oxford), Samantha Hoffman (MERICS), Regina Joseph (Pytho LLC), Elsa Kania (Harvard), Jaclyn Kerr (LLNL), Lydia Kostopoulos (LKCYBER), James A. Lewis (CSIS), Martin Libicki (USNA), Herbert Lin (Stanford), Kacie Miura (MIT), Roger Morgus (New America), Rachel Esplin Odell (MIT), Eleonore Pauwels (United Nations University), Lora Saalman (EastWest Institute), Jennifer Snow (USSOCOM), Laura Steckman (MITRE), Valentin Weber (Oxford) Air University Press Muir S. Fairchild Research Information Center Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama Opening remarks provided by: Library of Congress Cataloging-in- Publication Data Brig Gen Alexus Grynkewich (JS J39) Names: TBD. and Lawrence Freedman (King’s College, Title: Artificial Intelligence, China, Russia, and the Global Order : Techno- London) logical, Political, Global, and Creative Perspectives / Nicholas D. Wright. Editor: Other titles: TBD Nicholas D. Wright (Intelligent Biology) Description: TBD Identifiers: TBD Integration Editor: Subjects: TBD Mariah C. Yager (JS/J39/SMA/NSI) Classification: TBD LC record available at TBD AIR UNIVERSITY PRESS COLLABORATION TEAM Published by Air University Press in October -

A Study of Judges' and Lawyers' Blogs In

Copyright © 2011 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College. 2011 / Exercising Freedom of Speech behind the Great Firewall 251 reminding both of them of the significance of law, the legal and political boundaries set by the authorities are being pushed, challenged, and renegotiated. Drawing on existing literature on boundary contention and the Chinese cultural norm of fencun (decorum), this study highlights the paradox of how one has to fight within boundaries so as to expand the contours of the latter for one’s ultimate freedom. Judging from the content of the collected postings, one finds that, in various degrees, critical voices can be tolerated. What emerges is a responsive and engaging form of justice which endeavors to address grievances in society, and to resolve them in unique ways both online and offline. I. INTRODUCTION The Internet is a fascinating terrain. Much literature has been devoted to depicting its liberating democratic power in fostering active citizenry, and arguably, an equal number of articles have been written that describe attempts by various states to exercise control.1 China has provided a ready example to illustrate this tension. 2 And this study focuses on the blog postings by judges and public interest lawyers in order to understand better how the legal elites in China have deployed routine and regular legal discussion in the virtual world to form their own unique public sphere, not only as an assertion for their own autonomy but also as a subtle yet powerful form of contention against the legal and political boundaries in an authoritarian state. Chinese authorities are notorious for their determination to stamp out dissenting voices both online and offline. -

Chapter 3. Economic & Social Rights

Chapter 3. Economic & Social Rights 3.1. Women’s Rights Limited Positive Steps in Protecting Women 12 Recommendations Assessed: 186.84 (Central African Republic), 88 In this section, we assess the implementation of the (Palestine), 91 (Moldova), 92 (Bolivia), 2013 UPR recommendations on discrimination 93 (Eritrea), 95 (Moldova), 96 against women in employment and the right to pay (Romania), 97 (Mali), 98 (Botswana), equality, as well as on combating domestic violence 99 (Oman), 135 (Egypt), and 177 1 (Iceland) and human trafficking. China’s Replies: The Chinese government has made public pledges and 12 recommendations accepted taken some steps in legislation to protect women’s rights and promote gender equality. During its 84, 88, 91, 92, 93, 95, 96, 97, 98, 99, 135 & 177 successful re-election bid to the Human Rights Council in 2013, the government promised to 5 already implemented 2 88, 92, 96, 97 & 98 eliminate gender discrimination in employment. The State acknowledged in its 2014 report to CEDAW that 1 being implemented 177 China still faces problems and challenges in eliminating gender discrimination in many aspects of 3 NGO Assessment: life. In its National Human Rights Action Plan (2012- 2015), the government promised to “make efforts to China has partially implemented recommendations 88, 95 & 97, has eliminate gender discrimination in employment and not implemented the other seven realize equal payment for men and women doing the recommendations, and same work.” However, in its June 2016 assessment of recommendation 99 is the Action Plan’s implementation, it provided no inappropriate [not assessed] evidence of having taken any actions to reach the target.4 China took a major step forward by adopting its first Anti-Domestic Violence Law in December 2015 and enacting it in 2016 after decades of advocacy for such a legislation by women’s rights activists and academics.5 The adoption of the law drew welcome public attention to the issue of domestic violence.