Portrayal of Alcohol Consumption in Movies and Drinking Initiation in Low-Risk Adolescents

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Separations-06-00017-V2.Pdf

separations Article Perfluoroalkyl Substance Assessment in Turin Metropolitan Area and Correlation with Potential Sources of Pollution According to the Water Safety Plan Risk Management Approach Rita Binetti 1,*, Paola Calza 2, Giovanni Costantino 1, Stefania Morgillo 1 and Dimitra Papagiannaki 1,* 1 Società Metropolitana Acque Torino S.p.A.—Centro Ricerche, Corso Unità d’Italia 235/3, 10127 Torino, Italy; [email protected] (G.C.); [email protected] (S.M.) 2 Università di Torino, Dipartimento di Chimica, Via Pietro Giuria 5, 10125 Torino, Italy; [email protected] * Correspondences: [email protected] (R.B.); [email protected] (D.P.); Tel.: +39-3275642411 (D.P.) Received: 14 December 2018; Accepted: 28 February 2019; Published: 19 March 2019 Abstract: Per and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs) are a huge class of Contaminants of Emerging Concern, well-known to be persistent, bioaccumulative and toxic. They have been detected in different environmental matrices, in wildlife and even in humans, with drinking water being considered as the main exposure route. Therefore, the present study focused on the estimation of PFAS in the Metropolitan Area of Turin, where SMAT (Società Metropolitana Acque Torino S.p.A.) is in charge of the management of the water cycle and the development of a tool for supporting “smart” water quality monitoring programs to address emerging pollutants’ assessments using multivariate spatial and statistical analysis tools. A new “green” analytical method was developed and validated in order to determine 16 different PFAS in drinking water with a direct injection to the Ultra High Performance Liquid Chromatography tandem Mass Spectrometry (UHPLC-MS/MS) system and without any pretreatment step. -

Domenica 27 Settembre 2015

UNDER 16F CALENDARIO INCONTRI domenica 27 settembre 2015 PALESTRA RISULTATO FASE DATA GIRONE ORA INCONTRO LOCALITA' GARA 1° SET 2° SET 8,30 ABIRC IVREA RIVAROLO CANAVES G.S. SAN FRANCESCO 9,30 CDCCS COGNE ( AO ) PALLAVOLO SAN GIACOMO NO POLISPORTIVO 10,30 27/9/15 BCG.S. SAN FRANCESCO CCS COGNE ( AO ) RIVAROLO A 11,30 DAPALLAVOLO SAN GIACOMO NO IRC IVREA RIVAROLO CANAVES 12,30 ACIRC IVREA RIVAROLO CANAVES CCS COGNE ( AO ) FASE 13,30 BDG.S. SAN FRANCESCO PALLAVOLO SAN GIACOMO NO 8,30 ABCANAVESE VOLLEY PGS LA FOLGORE 9,30 GIRONI CDUNION VOLLEY SPRINT VIRTUS BIELLA 10,30 BCPGS LA FOLGORE UNION VOLLEY PRIMA 27/9/15 RIVARA B 11,30 DASPRINT VIRTUS BIELLA CANAVESE VOLLEY 12,30 ACCANAVESE VOLLEY UNION VOLLEY 13,30 BDPGS LA FOLGORE SPRINT VIRTUS BIELLA PUNTI POS GIRONE A 123456 INDIRIZZO PALAZZETTI A IRC IVREA RIVAROLO CANAVESE PALAZZETTO POLISPORTIVO RIVAROLO CANAVESE B G.S. SAN FRANCESCO C CCS COGNE ( AO ) VIA TRIESTE 84 10086 RIVAROLO CANAVESE ( TO ) D PALLAVOLO SAN GIACOMO NOVARA PALASPORT RIVARA CANAVESE PUNTI POS GIRONE B VIA GIORDANO BRUNO ‐ 10080 RIVARA CANAVESE ( TO ) 123456 A CANAVESE VOLLEY PALESTRA DI FAVRIA B PGS LA FOLGORE C UNION VOLLEY VIA LENIN SORMANO, 8 ‐ 10083 FAVRIA D SPRINT VIRTUS BIELLA FORMULA GARE DEL MATTINO : DUE SET FISSI CON UN PUNTO PER SET VINTO LE 1^ E 2^ CLASSIFICATE DI OGNI GIRONE ANDRANNO AGLI SCONTRI DIRETTI (SEMIFINALI‐FINALI) VALIDI DAL 1° AL 4° POSTO. LE 3^ E 4^ CLASSIFICATE DI OGNI GIRONE ANDRANNO AGLI SCONTRI DIRETTI (SEMIFINALI‐FINALI) VALIDI DAL 5° AL 8° POSTO. -

Progetto Territoriale Sistema Bibliotecario Di Ivrea E Canavese (To)

Progetto territoriale Sistema Bibliotecario di Ivrea e Canavese (To) Referente del progetto : Gabriella Ronchetti – Viviana D’Onofrio Biblioteca Civica di Ivrea 0125/410502 [email protected] Comune coordinatore : Ivrea (To) Sistema Bibliotecario di Ivrea e Canavese Centro rete Biblioteca Civica di Ivrea P.zza Ottinetti, 30 – 10015 IVREA Tel. 0125/410309 Fax 0125/45472 Indirizzo e-mail [email protected] Comuni coinvolti: 56 Comuni con le relative biblioteche civiche: Agliè, Albiano, Alice Castello, Banchette, Barbania, Bollengo, Borgaro Torinese, Borgofranco, Bosconero, Burolo, Caluso, Cascinette d'Ivrea, Caselle Torinese, Castellamonte, Cavaglià, Chiaverano, Ciconio, Ciriè, Colleretto Giacosa, Cossano, Cuorgnè, Favria, Forno Canavese, Ivrea, Lessolo, Locana, Mappano, Mathi, Mazzè, Montalto Dora, Nole, Oglianico, Orio Canavese, Ozegna, Pavone Canavese, Piverone, Pont Canavese, Pratiglione, Quincinetto, Rivara, Rivarolo Canavese, Rocca C.se, Rondissone, Rueglio, Samone, San Giorgio Canavese, Settimo Rottaro, Settimo Vittone, Sparone, Strambinello, Strambino, Tavagnasco Vauda Canavese, Vestignè, Vico Canavese, Villareggia Anno 2018 Un primo sguardo ai nostri volontari Numero di volontari coinvolti nel progetto NpL: 142 I volontari indicati si occupano ESCLUSIVAMENTE di NpL? Sì No X Se tra i volontari indicati SOLO ALCUNI si occupano 7 esclusivamente di NpL, indicare quanti sono sul totale: Se i volontari NON si occupano esclusivamente di NpL, descrivere come sono gestiti all’interno del progetto. I volontari che non si occupano esclusivamente di NpL si occupano dell’apertura delle biblioteche durante le letture ad alta voce organizzate a cura del Sistema bibliotecario; talvolta sono i volontari stessi a svolgere le mansioni di lettori per i bambini e le loro famiglie o per gli asili nido e le scuole dell’infanzia. -

Curriculum Vitae

CURRICULUM VITAE INFORMAZIONI PERSONALI Nome BARBATO SUSANNA Data di nascita 05/12/1972 Qualifica Segretario comunale Amministrazione COMUNE DI CUORGNE’ Responsabile Segreteria comunale convenzionata tra i Comuni di Incarico attuale Cuorgnè 50% e il Comune di Nole 50% Numero telefonico dell’ufficio 0124655210 E-mail istituzionale [email protected] TITOLI DI STUDIO E PROFESSIONALI ED ESPERIENZE LAVORATIVE Titolo di studio Laurea in economia conseguita presso l'Università degli studi di Torino il 18.03.1996 Altri titoli di studio e Iscritta all’Albo Nazionale dei Segretari Comunali e Provinciali per il professionali superamento del corso – concorso per l’accesso in carriera della durata di 18 mesi (gennaio 2002 – luglio 2003) seguito da 6 mesi di tirocinio pratico, presso la Scuola Superiore della Pubblica Amministrazione Locale – Roma. Dicembre 2006: conseguimento dell’idoneità a segretario generale (Fascia B) superando il relativo corso di abilitazione presso la Scuola Superiore della Pubblica Amministrazione Locale – Roma. Esperienze professionali (incarichi ricoperti) 01.02.1997 – 23. 12.2003 Comune di Rivara Responsabile del Servizio Economico Finanziario (ex VII q.f.) 29.12.2003 – 31.05.2007 Segretario Comunale (Fascia C) in convenzione fra i Comuni di Rivara e Ceresole Reale 01.06.2007 – 31.08.2009 Segretario comunale (Fascia B) in convenzione tra i Comuni di Rivara, Ceresole Reale e Cintano 01.09.2009 – 30.06.2013 Segretario Comunale (Fascia B) in convenzione tra i Comuni di Rivara, San Giorgio Canavese e Candia Canavese -

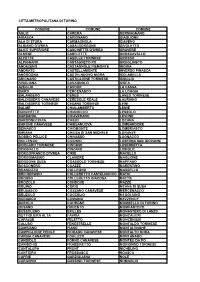

Città Metropolitana Di Torino Comune Comune Comune

CITTÀ METROPOLITANA DI TORINO COMUNE COMUNE COMUNE AGLIÈ CAREMA GERMAGNANO AIRASCA CARIGNANO GIAGLIONE ALA DI STURA CARMAGNOLA GIAVENO ALBIANO D'IVREA CASALBORGONE GIVOLETTO ALICE SUPERIORE CASCINETTE D'IVREA GRAVERE ALMESE CASELETTE GROSCAVALLO ALPETTE CASELLE TORINESE GROSSO ALPIGNANO CASTAGNETO PO GRUGLIASCO ANDEZENO CASTAGNOLE PIEMONTE INGRIA ANDRATE CASTELLAMONTE INVERSO PINASCA ANGROGNA CASTELNUOVO NIGRA ISOLABELLA ARIGNANO CASTIGLIONE TORINESE ISSIGLIO AVIGLIANA CAVAGNOLO IVREA AZEGLIO CAVOUR LA CASSA BAIRO CERCENASCO LA LOGGIA BALANGERO CERES LANZO TORINESE BALDISSERO CANAVESE CERESOLE REALE LAURIANO BALDISSERO TORINESE CESANA TORINESE LEINÌ BALME CHIALAMBERTO LEMIE BANCHETTE CHIANOCCO LESSOLO BARBANIA CHIAVERANO LEVONE BARDONECCHIA CHIERI LOCANA BARONE CANAVESE CHIESANUOVA LOMBARDORE BEINASCO CHIOMONTE LOMBRIASCO BIBIANA CHIUSA DI SAN MICHELE LORANZÈ BOBBIO PELLICE CHIVASSO LUGNACCO BOLLENGO CICONIO LUSERNA SAN GIOVANNI BORGARO TORINESE CINTANO LUSERNETTA BORGIALLO CINZANO LUSIGLIÈ BORGOFRANCO D'IVREA CIRIÈ MACELLO BORGOMASINO CLAVIERE MAGLIONE BORGONE SUSA COASSOLO TORINESE MAPPANO BOSCONERO COAZZE MARENTINO BRANDIZZO COLLEGNO MASSELLO BRICHERASIO COLLERETTO CASTELNUOVO MATHI BROSSO COLLERETTO GIACOSA MATTIE BROZOLO CONDOVE MAZZÈ BRUINO CORIO MEANA DI SUSA BRUSASCO COSSANO CANAVESE MERCENASCO BRUZOLO CUCEGLIO MEUGLIANO BURIASCO CUMIANA MEZZENILE BUROLO CUORGNÈ MOMBELLO DI TORINO BUSANO DRUENTO MOMPANTERO BUSSOLENO EXILLES MONASTERO DI LANZO BUTTIGLIERA ALTA FAVRIA MONCALIERI CAFASSE FELETTO MONCENISIO CALUSO FENESTRELLE MONTALDO -

CODICE PIEMONTE 432PIE1 Biogest Srl Via S. Giovanni Bosco

CODICE PIEMONTE PARTECIPAZIONE AL CIRCUITO Biogest s.r.l. Via S. Giovanni Bosco, 179 – Novi Ligure Via dell’Agricoltura 5/a – Novi Ligure MOCF MOCF 432PIE1 [email protected] massa aerodispersi FTIR COMIE SRL Via Taulè, 15 – 28070 Sizzano (NO): MOCF MOCF 17PIE2 [email protected] massa aerodispersi FTIR EcoAnalitica s.r.l. Via Poliziano 36 – 10136 Torino MOCF MOCF 388PIE3 [email protected] - [email protected] massa aerodispersi FTIR Eurolab s.r.l. Via Bardonecchia 4 – Nichelino (TO) MOCF MOCF 283PIE4 [email protected] massa aerodispersi FTIR Laboratorio Amianto del Politecnico di Torino Dip.dell'Ambiente, del Territorio e delle Infrastrutture – (ex DIP. DI INGEGNERIA DEL TERRITORIO, DELL’AMBIENTE E DELLE GEOTECNOLOGIE - LABORATORIO DI MICROSCOPIA [email protected]) Corso Duca degli Abruzzi, 24 - 10129 TORINO MOCF MOCF 173PIE5 politecnicoditorino @pec.polito.it massa aerodispersi Idrogeolab s.r.l. MOCF MOCF 132PIE6 Via Santi 29 – Alessandria : [email protected] massa aerodispersi DRX FTIR L.A.R.A. s.r.l. Via degli Artigiani, 7 – 10042 Nichelino (TO) MOCF MOCF 72PIE8 [email protected] massa aerodispersi FTIR Nuovi Servizi Ambientali Viale Kennedy, 10-Robassomero (TO) MOCF MOCF 405PIE9 [email protected] massa aerodispersi FTIR PROTEZIONE AMBIENTALE S.R.L. VIA DELL’AUTOMOBILE 6/8 – Zona industriale MOCF MOCF 130PIE10 D3 15100 ALESSANDRIA : [email protected] massa aerodispersi FTIR Viale Copperi, n. 15 – 10070 – Balangero (TO) R.S.A. srl - Società per il Risanamento e lo Sviluppo Ambientale della ex miniera di amianto MOCF 374PIE11 di Balangero e Corio [email protected] aerodispersi Statale Valsesia, 20 – 13035 Lenta (VC) TECNO PIEMONTE S.P.A. -

Il Problema Abitativo Delle Famiglie Straniere. Gli Aiuti Pubblici Sociali Ed Economici: Le Assegnazioni Di Case Popolari Ed I Contributi Per Il Sostegno All’Affitto

Città Metropolitana di Torino Regione Piemonte (già Provincia di Torino) Osservatorio Fabbisogno Abitativo Sociale Osservatorio Condizione Abitativa Il problema abitativo delle famiglie straniere. Gli aiuti pubblici sociali ed economici: le assegnazioni di case popolari ed i contributi per il sostegno all’affitto. A cura di Stefania Falletti Città Metropolitana di Torino Laura Schutt Scupolito Regione Piemonte I contenuti dello studio Vengono analizzati due distinti segmenti di fabbisogno abitativo sociale delle famiglie straniere: la domanda di casa popolare e la richiesta di contributi economici per il sostegno all’affitto di abitazioni sul libero mercato. Entrambi gli aiuti presuppongono la domanda da parte dei diretti interessati ed il possesso di determinati requisiti d’accesso 1. Viene valutata la capacità di risposta degli enti pubblici locali rispetto a queste due tipologie di fabbisogno determinando sia il numero di alloggi di edilizia residenziale pubblica assegnati a famiglie straniere che l’ammontare dei contributi pubblici offerti alle famiglie straniere quale contributo per il sostegno all’affitto. Sono evidenziati i paesi di provenienza delle famiglie beneficiarie degli aiuti e la relativa residenza nella provincia di Torino. Trattando di materie specifiche/tecniche riferite alle problematiche abitative con riferimenti alla legislazione regionale in materia di edilizia sociale e alla legislazione nazionale in materia di aiuti economici per l’affitto, è stato inserito al fondo della relazione un breve glossario per permettere una miglior comprensione degli acronimi e dei riferimenti tecnico/legislativi. L’arco temporale esaminato Per quanto concerne le case popolari si è fatto riferimento all’anno 2014 e all’andamento delle assegnazioni effettuato dai Comuni nel quinquennio 2010 – 2014; mentre l’analisi sul contributo economico di sostegno al pagamento dell’affitto fa riferimento all’anno 2014 e alla sommatoria delle precedenti tre edizioni emesse dalla Regione Piemonte. -

Uffici Locali Dell'agenzia Delle Entrate E Competenza

TORINO Le funzioni operative dell'Agenzia delle Entrate sono svolte dalle: Direzione Provinciale I di TORINO articolata in un Ufficio Controlli, un Ufficio Legale e negli uffici territoriali di MONCALIERI , PINEROLO , TORINO - Atti pubblici, successioni e rimborsi Iva , TORINO 1 , TORINO 3 Direzione Provinciale II di TORINO articolata in un Ufficio Controlli, un Ufficio Legale e negli uffici territoriali di CHIVASSO , CIRIE' , CUORGNE' , IVREA , RIVOLI , SUSA , TORINO - Atti pubblici, successioni e rimborsi Iva , TORINO 2 , TORINO 4 La visualizzazione della mappa dell'ufficio richiede il supporto del linguaggio Javascript. Direzione Provinciale I di TORINO Comune: TORINO Indirizzo: CORSO BOLZANO, 30 CAP: 10121 Telefono: 01119469111 Fax: 01119469272 E-mail: [email protected] PEC: [email protected] Codice Ufficio: T7D Competenza territoriale: Circoscrizioni di Torino: 1, 2, 3, 8, 9, 10. Comuni: Airasca, Andezeno, Angrogna, Arignano, Baldissero Torinese, Bibiana, Bobbio Pellice, Bricherasio, Buriasco, Cambiano, Campiglione Fenile, Cantalupa, Carignano, Carmagnola, Castagnole Piemonte, Cavour, Cercenasco, Chieri, Cumiana, Fenestrelle, Frossasco, Garzigliana, Inverso Pinasca, Isolabella, La Loggia, Lombriasco, Luserna San Giovanni, Lusernetta, Macello, Marentino, Massello, Mombello di Torino, Moncalieri, Montaldo Torinese, Moriondo Torinese, Nichelino, None, Osasco, Osasio, Pancalieri, Pavarolo, Pecetto Torinese, Perosa Argentina, Perrero, Pinasca, Pinerolo, Pino Torinese, Piobesi Torinese, Piscina, Poirino, Pomaretto, -

Strada Gran Paradiso 2014

BASSO CANAVESE COLLERETTO CASTELNUOVO STRADA GRAN PARADISO 5 Ozegna, Feletto, Rivarolo Canavese, San Benigno Canavese 2014 Domenica 21 settembre 2014 Sabato 27 settembre 2014 Ore 16,00 Visita guidata di Colleretto Castelnuovo OZEGNA Ore 18,00 “La capra di Theodoro” di e con Aldo Querio Gianetto, spettacolo Ore 09,00 Colazione. Istruzioni per l’uso teatrale presso la Torre tratto da una vicenda del 1730 recuperata Visita guidata al Castello dagli archivi storici di Colleretto Castelnuovo (in caso di maltempo Ore 10,20 Processione di San Besso lo spettacolo avrà luogo nel Salone comunale) con accompagnamento della Banda Musicale STRADA GRAN PARADISO SEI ITINERARI ALLA SCOPERTA DEL Ore 19,30 Spostamento (con mezzi propri) a Santa Elisabetta CANAVESE OCCIDENTALE Ore 20,00 Cena presso la trattoria Minichin a Santa Elisabetta Feletto *PernottaMento A Colleretto Castelnuovo 2014 Ore 11,00 Visita al Museo dell’Oro Trattoria Minichin Santa Elisabetta Tel. 0124/690037 DOMENICA 13 LUGLIO: Ore 12,15 Dimostrazione degli Sbandieratori di Feletto Le camere dell’Antico Castello Tel. 0124/699910 1. NOASCA E CERESOLE REALE Ore 12,30 Visita Chiesa di Santa Maria Assunta ITINERARI TRA NATURA, Ore 13,30 PRANZO presso la Locanda Dei Templari DOMENICA 14 SETTEMBRE: VALLE SACRA CULTURA, STORIA E TRADIZIONI 2. VALLE ORCO: Locana, Ribordone, 6 Castelnuovo Nigra, Cintano, Borgiallo, Chiesanuova, Castellamonte 3. VALLE SOANA: Valprato Soana, Ronco Canavese, Ingria Rivarolo Canavese Ore 15,00 Visita guidata al Castello Malgrà o al centro storico Domenica 28 settembre 2014 DOMENICA 21 SETTEMBRE: a cura dell’Ass. Amici del Castello Malgrà Castelnuovo NIGRA - VILLA Castelnuovo 4. ALTO CANAVESE: Rivara, Pratiglione, Valperga, San Ponso Canavese Nel Parco del Castello Malgrà: Punto di promozione del territorio con Sabato 12 e Ore 9,30-10 Visita guidata alla Chiesa, alle rovine del castello dei conti 5. -

PINEROLO - CERESOLE REALE (Lago Serrù) Km 196 13 Cronotabella Venerdì 24 Maggio 2019

COMUNE DI RUBIANA - Prot 0001208 del 14/03/2019 Tit IX Cl 2 Fasc 0 COMUNE DI RUBIANA - Prot 0001208 del 14/03/2019 Tit IX Cl 2 Fasc 0 Tappa PINEROLO - CERESOLE REALE (Lago Serrù) km 196 13 cronotabella venerdì 24 maggio 2019 Distanze Orario di passaggio Quota Località Note par- per- da per- km / h ziali corse correre 33 35 37 PROVINCIA DI TORINO 325 PINEROLO # Villaggio di Partenza 2.8 11.30 11.30 11.30 337 PINEROLO # km 0 0.0 0.0 196.0 11.35 11.35 11.35 364 Frossasco # sp.195-sp.589 6.9 6.9 189.1 11.45 11.45 11.44 290 Bivio di Cumiana : sp.146 6.6 13.5 182.5 11.54 11.53 11.52 621 Colletta di Cumiana # sp.193 3.8 21.5 174.5 12.11 12.09 12.07 506 Giaveno # sp.190 4.9 26.4 169.6 12.17 12.15 12.13 352 Avigliana # Ponte Dora - sp. 197 7.8 34.2 161.8 12.28 12.25 12.22 357 Almese # sp.197 5.9 40.1 155.9 12.37 12.34 12.31 1311 Colle del Lys # sp.197 14.2 54.3 141.7 13.18 13.11 13.05 1116 Col San Giovanni # sp.197 7.8 62.1 133.9 13.29 13.21 13.15 787 Viu' ; sp.32 7.3 69.4 126.6 13.38 13.31 13.24 505 Germagnano # Ponte Stura di Lanzo-sp;2 13.0 82.4 113.6 13.56 13.47 13.40 467 Lanzo Torinese # v.Umberto I - sp.2 2.5 84.9 111.1 13.59 13.51 13.43 408 Mathi # sp.2 6.1 91.0 105.0 14.07 13.58 13.50 375 Nole : v.Rocca-sp.25 3.1 94.1 101.9 14.12 14.02 13.54 Rifornimento/Feed zone: km 95 - 98 # 417 Rocca Canavese ; sp.23 8.4 102.5 93.5 14.25 14.15 14.06 370 Rivara ; sp.42 6.0 108.5 87.5 14.33 14.23 14.14 317 Busano # v.Valperga-sp. -

GAL Valli Del Canavese Corso Ogliani, 9 10080 RIVARA (TO)

GAL Valli del Canavese Corso Ogliani, 9 10080 RIVARA (TO) Regione Piemonte Programma di Sviluppo Rurale 2007‐2013 Asse IV Leader Programma di Sviluppo Locale “IMPRENDITORIA GIOVANILE: LA LEVA PER UN TERRITORIO CHE CRESCE” BANDO PUBBLICO PER LA PRESENTAZIONE DI DOMANDE DI FINANZIAMENTO Locande tipiche delle Valli del Canavese Mis 313.2.b Allegati: Allegato A Modulo di domanda di contributo (previsto nella procedura informatica per l’invio on‐ line e come conferma cartacea) con i seguenti allegati: Allegato A.1 Schema di accordo per la gestione in forma associata dei servizi Allegato A.2 Dichiarazione di assenso da parte del proprietario Allegato A.3 Dichiarazione in materia di de minimis Allegato A.4 Disciplinare prestazionale Allegato A.5 Manuale di tipicizzazione Allegato A.6 Descrizione del progetto Allegato A.7 Scheda di presentazione del servizio di prenotazione Citybreak Allegato A.8 Impegno alla sottoscrizione dell’accordo commerciale Allegato A.9 Impegno alla realizzazione del sito web Allegato A.10 Dichiarazione della capacità ricettiva e ristorativa della struttura Allegato B Schema di garanzia fideiussoria per la richiesta di anticipo Allegato C Dichiarazione di conclusione dell’intervento e richiesta di collaudo Allegato D Modello di targa/cartello informativo sui contributi FEASR con cui contrassegnare i beni e/o gli immobili oggetto degli interventi 1 PARTE I – INQUADRAMENTO DELLA MISURA Articolo 1 ‐ Amministrazione aggiudicatrice 1. Il Gruppo di Azione Locale (GAL) Valli del Canavese, utilizzando le risorse finanziarie rese disponibili in applicazione del Programma di Sviluppo Rurale 2007/2013 ‐ Asse 4 LEADER, concede contributi per la realizzazione degli interventi descritti al successivo art. -

Cognome Nome M/F Nato Mat. Sez

COGNOME NOME M/F NATO MAT. SEZ. Abate Antonio M 28.06.60 Torino 1979 D Abate Carlo M 19.02.72 Torino 1991 E Abbà Beatrice F 10.05.56 Rivoli (To) 1975 E Abbà Chiara F 29.04.52 Torino 1971 E Abbate Giuseppe M 10.01.29 Torino 1947 B Abbona Giuseppina F 20.01.31 Pola 1949 A Abbona Rosangela F 06.06.54 Clavesana (Cn) 1974 A Accardi Anna Maria F 24.05.61 Torino 1981 A Accornero Luciano M 04.01.31 Grugliasco 1949 B Accornero Maria Luisa F 19.07.37 Torino 1956 A Acotto Alberto M 24.04.60 Torino 1979 C Actis Valentina F 15.09.71 Torino 1990 C Actis Camporeale Attilio M 12.06.79 Torino 1997 D Actis Maria Vittoria F 24.01.54 Torino 1973 D Actis Roberto M 01.03.59 Torino 1978 B Adamo Anna Teresa F 01.03.32 Bolzano 1951 B Adda Maria F 15.03.74 Torino 1993 D Addario Giuseppina F 19.06.21 Torino 1940 A Addis Giacomino M 20.03.12 Luras 1935 B Adelendi Tiziana F 02.10.74 Torino 1993 A/F Adreani Maria F 26.11.28 Torino 1947 B Agagliate Marco M 11.10.70 Torino 1989 B Ageno Renzo M 23.08.57 Torino 1977 B Aghemo Aurelio M 24.11.49 Torino 1969 C Aghilar Leonilde F 12.01.75 Torino 1994 A/F Aghina Francesca F 08.04.69 Busto Arsizio (Va) 1988 B Aghina Giacomo M 05.10.70 Cuneo 1989 A Aglietta Federica F 29.07.53 Savona 1972 C Aglietta Maria Adelaide F 04.06.40 Torino 1959 A Agnello Elena F 11.06.75 Torino 1994 B Agodi Graziella F 14.07.48 Torino 1967 A Agosti Aldo M 05.06.43 Torre Pellice (To) 1962 A Agosto Aldo M 25.01.55 Torino 1974 E Agosto M.