STRATEGIC RATIONALE Should a Firm Build a Strategic Alliance?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Picsearch Announces Alliance with Lycos, Inc. - Image Search for Lycos Multimedia Search to Be Powered by Picsearch

2005-05-02 12:00 CEST Picsearch announces alliance with Lycos, Inc. - Image search for Lycos Multimedia Search to be powered by Picsearch STOCKHOLM, Sweden, May 2, 2005 - Picsearch announced today that it has entered into a syndication agreement to supply U.S. internet brand Lycos, Inc. with image search services for Lycos' Multimedia Search. This agreement brings Picsearch image search technology to millions of Lycos users. Nils Andersson, CEO of Picsearch, said "We are extremely proud that Lycos, Inc. is harnessing our image search technology. They are a great addition to the list of leading web names that have chosen the Picsearch image search service because we provide images that are continually updated, uniquely filtered and highly relevant to the users' queries. We will continue to provide the highest quality image search on the net." Lycos (www.lycos.com) is one of the leading Internet destinations in the U.S. At its center is Lycos Search. Now, thanks to Picsearch, Lycos users have access to hundreds of millions of images, enabling them to refine their image search criteria to meet their exact requirements. "We recently re-launched our Lycos.com homepage with a key focus on search, including multimedia search," said Adam Soroca, General Manager of Search Services for Lycos, Inc. "Picsearch delivers the high-quality, relevant image search results our users search for everyday." About Picsearch Picsearch AB creates the image search solutions that power visual search for many of the Web's leading properties. The company syndicates its technology to search engines and portals to enable them to complete their own search package by acquiring powerful image search capabilities. -

Simplify Your Digital Life LYCOS Announces the Launch of Brightcom

Simplify your Digital Life _________________________________________________________________________ LYCOS Announces the Launch of Brightcom Gali Arnon to be the CEO of Brightcom Hyderabad, India and Herziliya, Israel, April 20, 2016: LYCOS (NSE: LYCOS I BSE: 532368), the global Internet brand, today announced that the company is working on a meaningful and widespread reorganization of the group. These changes are designed to simplify the way LYCOS interacts with customers, partners, investors and world at large. This move will facilitate the organization in becom- ing more nimble and responsive. In line with the above plan, the company made the first major announcement today. BRIGHTCOM powered by LYCOS Brightcom brings together the legacy of ‘Ybrant Digital’ alongside the ‘Brightcom’ Media initiative. This combines data-driven technology together with the company’s strong bonds with advertisers and publishers, all in one consolidated platform. The motto of the brand is ‘Leading through technology, winning through people’. The global expert team, be it in APAC, Israel, Europe, USA or Latin America, offers know-how and perspective, which are shaped into a strategy and a plan of action eventually executed to meet the clients’ goals. The current operations will remain intact. If anything, they will only get better. There are new prod- ucts, exclusive media-assets and new offices, waiting to be unveiled soon. Gali Arnon will take on the role of CEO of Brightcom. She is a natural choice to take up this role due to her initiative in bringing together the core idea and the entire business plan for Brightcom. She will transition out of her current role as the General Manager of the Advertising Division of LYCOS, Ybrant Digital. -

Terra Lycos: Creating a Global and Profitable Integrated Media Company

INSEAD Terra Lycos: Creating a Global and Profitable Integrated Media Company INSPECTIONNot For Reproduction COPY 06/2002-5042 This case was written by Patricia Reese, Research Associate, under the supervision of Soumitra Dutta, The Roland Berger Chaired Professor of E-Business and Information Technology, and Theodoros Evgeniou, Assistant Professor of Information Systems, all at INSEAD. It is intended to be used as a basis for class discussion rather than to illustrate either effective or ineffective handling of an administrative situation. Copyright © 2002 INSEAD, Fontainebleau, France. N.B. PLEASE NOTE THAT DETAILS OF ORDERING INSEAD CASES ARE FOUND ON THE BACK COVER. COPIES MAY NOT BE MADE WITHOUT PERMISSION. INSPECTIONNot For Reproduction COPY INSEAD 1 5042 “Market leadership is a challenge within our reach, but requires us to achieve several objectives: consolidating our product offerings to make our portals the most comprehensive and compelling on the World Wide Web, taking advantage of our extraordinary cash position to grow profits and extend our website network, and finally offering small- and medium-sized businesses effective e-commerce solutions. Terra Lycos must make full use of our advantage in the convergence of media, communications and interactive content, thanks to strategic alliances with Telefónica, our majority stockholder, and Bertelsmann.” Joaquim Agut, Executive Chairman, Terra Lycos The bright mid-September morning had not started well for Rafael Bonnelly, Terra Lycos’ vice-presidentNot For of content Reproduction management. He had just found out that FIFA,1 the governing body INSPECTIONof World Cup soccer, had given COPY the nod to Yahoo! to design and manage the official 2002 World Cup website. -

Marketing Digital Media Worldwide

Marketing Digital Media Worldwide Ybrant buys Lycos for $36 Million Lycos Inc., the leading brand of search based internet properties and services. Daum Communications will focus on Korean domestic business after this sale. Hyderabad, India, August 16, 2010: Ybrant Digital, the end-to-end provider of digital marketing solutions, today announced the signing of the stock purchase agreement to acquire Lycos Inc., the leading brand of search based internet properties and services from Daum Communications. Ybrant’s well known brands include Oridian, AdDynamix, dream ad, Max Interactive and VoloMP. Lycos consistently averages 12 - 15 million monthly unique visitors in the U.S., and is a top 25 Internet destination worldwide, reaching nearly 60 million unique visitors globally. The Lycos Network of sites and services includes Lycos.com, Tripod, Angelfire, Gamesville, and HotBot. Together, these sites and service help bring people together to interact, to find new friends, and to express themselves in positive, powerful ways. Daum reorganized the business of Lycos in 2009 and has turned Lycos profitable. As a result of the sale of Lycos, Daum will be able to devote its energy and corporate resources in order to find new potential growth business and future-oriented pipeline such as mobile, LBS, SNS and Search. “Brand Lycos needs no introduction, we are excited to bring in the Lycos properties into our fold.” said Suresh Reddy, Chairman and CEO, Ybrant Digital. “The quality of content and tools offered by Lycos has always attracted the best of the consumers across the world. Our goal is to combine the benefits of Ybrant’s global network with what Lycos has to offer in creating a compelling global destination for our advertising clients worldwide. -

Lycos Internet Ltd

Equitymaster Agora Research Private Limited 11 May, 2016 Lycos Internet Ltd. Market data Company overview Current price* Rs 17.6 (BSE) LYCOS Internet Limited offers digital marketing solutions to businesses, Market cap * Rs 8382 m agencies and online publishers around the world. The company is one of the original and most widely known internet brands in the world. The Face value Rs 2 company has evolved from one of the first search engines on the web, into BSE Code 532368 a comprehensive digital media destination for consumers across the No. of shares 476.3 m world. The company's segments include Digital Marketing and Software Free float 60.8% Development. The company's products and services include tools for 52 week H/L* Rs 47.2 /14.3 blogging, web publishing and hosting, online games, e-mail and search. *as on 10th May 16 The Company's network of sites and services include Lycos.com, Tripod, Angelfire, HotBot, Gamesville, WhoWhere and LYCOS Mail. The company also provides information technology implementation and Rs 100 invested is now worth outsourcing services. The company's LYCOS Life division is focused on BSE500 Lycos Internet Ltd. consumer internet products. 180 Company strengths 140 The launch of LYCOS Life division during the year have opened many 100 avenues for the company in the Internet of Things (IoT) space. The market 60 has been very positive of this product both in India and in the US. The Apr-15 Oct-15 Apr-16 company’s media division is positioned well than its peers. It recently added some of the leading publishers to its portfolio such as Play Buzz’, Stock price performance The Denver Post, Gannett Broadcasting, etc. -

Cie and Terra Lycos Celebrate Marketing and Strategic Alliance

CIE AND TERRA LYCOS CELEBRATE MARKETING AND STRATEGIC ALLIANCE § This alliance will be focused in the development of joint marketing strategies, including webcasting of various live entertainment events. Mexico City, November 30, 2000 – Corporacion Interamericana de Entretenimiento S.A. de C.V. (“CIE” or “the Company”) (BMV: CIE B), the leading live entertainment company in Latin America, today announced that it has established an alliance with Terra Lycos Mexico, a subsidiary of Terra Lycos (MC: TRR; Nasdaq: TRLY), the leading Internet company in the Spanish and Portuguese-speaking markets, to provide access to a great diversity of CIE’s contents and advertising platforms, through the development of various marketing strategies, including webcasting of live events, aimed at promoting Terra Lycos’ portal in Mexico. Arturo Galván, the country manager of Terra Lycos in Mexico, commented: “With this alliance Terra Lycos and CIE will develop joint marketing, diffusion and coverage of games, shows and spectacles which will be staged in the best venues and auditoriums of the country, as well as access to webcasting of a diverse and renowned artists and performances, nationally and internationally. With this alliance, more than three million Mexican users that integrate the Internet community of Terra Lycos, will enjoy a great diversity of events and entertainment by accessing Terra Lycos’ portal (www.terra.com.mx). With this agreement, “Terra Lycos and CIE will do the entertainment more yours than ever.” Rodrigo González Calvillo, Chief Operating Officer of CIE, mentioned: “The alliance we have reached with Terra Lycos, the leading Internet company in the Spanish and Portuguese-speaking markets, will allow CIE in the next years to develop one of the most complete marketing programs in Mexico, through an important range of services and products that we have in the country, including this great new media, the Internet. -

Creating Impressions Worldwide

Creating impressions worldwide Annual Report, 2009-10 01 Corporate information 02Ybrant’s story 05 Technology quotient 06 Letter from the Chairman’s desk 10 Creating waves 12 Creating impressions worldwide 16 Key acquisitions and tie-ups 19 Business divisions Contents 20 What makes Ybrant tick 22 Our clientele 25 Ybrant in India 26 Board of Directors & key managerial personnel 34 Management discussion & analysis 44 Directors’ Report 48 Corporate Governance Report 52 Financial Statements Corporate information REGISTERED OFFICE Dream ad S.A, Panama Plot No.7A, Road No.12, Av. Samuel Lewis y Calle 50, MLA Colony, Banjara Hills, Panama city, Panama. Hyderabad – 500 034 Andhra Pradesh, India. Dream ad S.A , Uruguay Phone: +91 (40) 4567 8999 Ellauri 357,Of. 50, 2Piso, Email: [email protected] Montevideo,Uruguay CP. 11300. Website: www.ybrantdigital.com Get Media Mexico S.A. DE CV BRANCH OFFICE Presidente Masaryk No. 111, 1er. Piso, 1201 West, 5th Street, Suite 300, Col. Chapultepec Morales, Los Angeles, CA 900017, USA. Mexico D.F. SUBSIDIARIES Max Interactive Pty Ltd Frontier Data Management Inc (MediosOne) 5 Kings Lane, 108 West, 13th Street, Wilmington, Darlinghurst, Delaware 19801, USA. NSW 2010, Australia. International Expressions Inc (VoloMP) 108 West, 13th Street, Wilmington, BANKERS Delaware 19801, USA. ING Vysya Bank Limited, Banjara Hills, Hyderabad, Pennyweb Inc (AdDynamix) Andhra Pradesh, India. 1201, West 5th Street, Suite 300, Los Angeles, CA 90017, USA. AUDITORS M/s. P. MURALI & CO., Online Media Solutions Limited (Oridian) Chartered Accountants, Sapir 3 Herzlia 46733, 6-3-655/2/3, Somajiguda, PO Box 12637, Israel. Hyderabad - 500 082, Andhra Pradesh, India. -

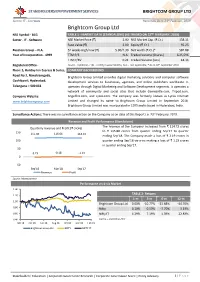

Brightcom Group Ltd

STAKEHOLDERS EMPOWERMENT SERVICES BRIGHTCOM GROUP LTD SECTOR: IT - SOFTWARE REPORTING DATE: 23RD FEBRUARY, 2019 Brightcom Group Ltd NSE Symbol - BCG TABLE 1 - MARKET DATA (STANDALONE) (AS TRADED ON 22ND FEBRUARY, 2019) Sector - IT - Software NSE Market Price (`) 2.90 NSE Market Cap. (₹ Cr.) 138.11 Face Value (`) 2.00 Equity (` Cr.) 95.25 Business Group – N.A. 52 weeks High/Low (₹) 5.90/2.30 Net worth (₹ Cr.)* 582.88 Year of Incorporation - 1999 TTM P/E N.A. Traded Volume (Shares) 6,25,596 TTM P/BV 0.24 Traded Volume (lacs) 18.14 Registered Office - Source - Capitaline, TTM - Trailing Twelve Months, N.A. - Not Applicable, * As on 30th September 2018 Floor: 5, Holiday Inn Express & Suites, COMPANY BACKGROUND Road No 2, Nanakramguda, Brightcom Group Limited provides digital marketing solutions and computer software Gachibowli, Hyderabad, development services to businesses, agencies, and online publishers worldwide. It Telangana – 500 032 operates through Digital Marketing and Software Development segments. It operates a network of community and social sites that include Gamesville.com, Tripod.com, Company Website: Angelfire.com, and Lycos.com. The company was formerly known as Lycos Internet www.brightcomgroup.com Limited and changed its name to Brightcom Group Limited in September 2018. Brightcom Group Limited was incorporated in 1999 and is based in Hyderabad, India. rd Surveillance Actions: There was no surveillance action on the Company as on date of this Report i.e. 23 February, 2019. Revenue and Profit Performance (Standalone) The revenue of the Company increased from ₹ 114.72 crores Quarterly revenue and Profit (₹ CRORE) 150 to ₹ 115.88 crores from quarter ending Sep’17 to quarter 115.88 116.64 114.72 ending Sep’18. -

Premium: Brightcom Group: for Hefty Gains!

Premium: Brightcom Group: For Hefty Gains! Dated 17 April 21 and Vol. XXX No.25| (Code: 532368) (FV: Rs.2) (CMP: Rs.8) Incorporated in 1999, the Brightcom Group (BCG), formerly known as Lycos Internet, is an Indian service company engaged in providing digital marketing services and development of computer software and services. It is a lso a global information technology (IT) implementation and outsourcing services provider. It has a presence across India, USA, Australia, Israel, Brazil, Argentina, Uruguay etc. and has 463 employees and consultants working in 22 offices spread across the world. Its software development services are based in India. It has 2 Indian subsidiaries and 14 subsidiaries. Lycos was acquired by Ybrant in 2010 for $36 million and renamed as Lycos Internet Ltd. In 2018, Lycos Internet was renamed to Brightcom Group L td. It was ready with changes required to conform to the European General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). It increased its service offerings in Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning. Brightcom Group was featured among Fortune India 500 in 2019. BCG offers digital marketing solutions to businesses, agencies and online publishers around the world. Over the period of next twenty years, BCG became a global player in digital marketing and related platforms by successfully acquiring and integrating 10 acquisitions. It has offices in the US, Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Uruguay, Mexico, UK, France, Germany, Sweden, Ukraine, Serbia, Israel, China, India, and Australia and with representatives or partners in Poland and Italy. BCG provides enterprise solutions and specializes in enterprise resource planning (ERP) solutions, Microsoft and open-source systems development. -

Simplify Your Digital Life Lycos TV Adds

Simplify your Digital Life ______________________________________________________________________________________ Lycos TV Adds Cool New Content to its Entertainment Channel The “One Question Interviews” by Rick Yaeger Hyderabad, December 04, 2014: Lycos TV announced the addition of new content from Actor/Executive Producer Greg Grunberg, under Entertainment Channel, “The One Question Interviews” by Rick Yaeger. This wildly popular, unconventional interview show is already on the channel www.lycostv.com. Celebrity guests include Chris Gorham, Sendhil Ramamurthy, Reno Wilson, Josh Malina, Tony Goldwyn, Vanna White, Derek Theler, Ken Leung, Neil Jackson and many other personalities from TV, Film, Music, & Sports. The One Question Interviews by Rick Yaeger is a show where celebrity guests are given an opportunity to share their latest work or important cause. The conversation of the show leads up to the moment when a single conversation starter interview question is chosen at random from a deck of cards and discussed. Rick Yaeger is known for his work on The Lab with Leo Laporte (2007), Easy to Assemble (2008) and One Question Interviews (2013). Rick is a resource for people in the entertainment industry who want to master social media and distribute their content online. About Lycos TV LycosTV is the premium destination for all things video on Lycos.com. It is a visually beautiful experience, utilizing our own HD player. All content will be placed into “channels”, like Entertainment, Food, News, etc., that each user will be able to ultimately customize based on his/her interests. Visit: www.lycostv.com About Lycos: Lycos is one of the original and most widely known Internet brands in the world, evolving from one of the first search engines on the web, into a comprehensive digital media destination for consumers across the world. -

Terra Lycos: Profiting from Information Products

INSEAD Terra Lycos: Profiting from Information Products 05/2003-5108 This case was written by Theodoros Evgeniou, Assistant Professor of Information Systems, at INSEAD, based on public material and on the earlier case Terra Lycos: Creating a Global and Profitable Integrated Media Company written by Patricia Reese, Research Associate, under the supervision of Soumitra Dutta, the Roland Berger Chaired Professor of E-Business and Information Technology, and Theodoros Evgeniou, Assistant Professor of Information Systems, all at INSEAD. It is intended to be used as a basis for class discussion rather than to illustrate either effective or ineffective handling of an administrative situation. Copyright © 2003 INSEAD, Fontainebleau, France. N.B. PLEASE NOTE THAT DETAILS OF ORDERING INSEAD CASES ARE FOUND ON THE BACK COVER. COPIES MAY NOT BE MADE WITHOUT PERMISSION. INSEAD 1 5108 On a bright mid-September morning in 2002, Rafael Bonnelly, Terra Lycos’ vice-president of content management, was examining the traffic and revenues from his company’s websites. The message was clear: visitors to his portal spent most of their time in ‘user generated’ sites, such as chat rooms, personal web hosting, email, etc, which, unfortunately, generated very little, if any, revenue per visitor. Although the ‘Terra generated’ content, such as news and music sites that Bonnelly’s global team spent its time and budget creating yielded higher revenues per visitor, it attracted less people, for less time, and for not enough revenues. The goal was clear: have Terra’s customers visit Terra generated sites more often while at the same time make them pay more for all sites and services. -

Father of Internet Search Comes Back to LYCOS LYCOS Founder Michael (Fuzzy) Mauldin Returns As a Director Hyderabad & Waltha

Simplify your Digital Life ______________________________________________________________________________ Father of Internet Search comes back to LYCOS LYCOS founder Michael (Fuzzy) Mauldin returns as a Director Hyderabad & Waltham: August 24, 2015 – LYCOS, (NSE & BSE: ‘LYCOS’ or the company), one of the most widely known Internet brands and one of the first search engines on the web is delighted to welcome back the creator of LYCOS, Michael L. Mauldin, to serve as an Independent Director on its Board. The appointment is effective on August 24, 2015. Mauldin, the founder of LYCOS in 1994 also served as the Chief Scientist of the Lycos Internet search engine company. Mauldin developed the Lycos Search Engine while working on the Informedia Digital Library project at Carnegie Mellon University. He is also former director of Conversive, Inc., an Artificial Intelligence Software company based in Malibu, California. "We are delighted to welcome the creator of LYCOS on to the company board. This appointment brings solid value to the company in terms of broad basing the board composition. More importantly this provides us access to Michael's experience and deep insights in the technology domain." said Suresh Reddy, Chairman & CEO of LYCOS. Since leaving LYCOS in 1998, Mauldin has written two books, ten refereed papers and several technical reports on natural language, autonomous information agents, information retrieval and expert systems. He is also one of the authors of Rog-O-Matic and Julia. "Twenty years ago Lycos changed the way the world accessed online information, and I hope to help Lycos change the world again as we tame the wilderness of wearable technology and the Internet of Things," said Mauldin.