Sound Symbolism of Gender in Cantonese First Names

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Two Vernacular Features in the English of Four American-Born Chinese Amy Wong New York University

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by ScholarlyCommons@Penn University of Pennsylvania Working Papers in Linguistics Volume 13 2007 Article 17 Issue 2 Selected Papers from NWAV 35 10-1-2007 Two Vernacular Features in the English of Four American-born Chinese Amy Wong New York University This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. http://repository.upenn.edu/pwpl/vol13/iss2/17 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Two Vernacular Features in the English of Four American-born Chinese This conference paper is available in University of Pennsylvania Working Papers in Linguistics: http://repository.upenn.edu/pwpl/ vol13/iss2/17 Two Vernacular Features in the English of Four American-Born Chinese in New York City* Amy Wong 1 Introduction Variationist sociolinguistics has largely overlooked the English of Chinese Americans, sometimes because many of them spoke English non-natively. However, the number of Chinese immigrants has grown over the last 40 years, in part as a consequence of the 1965 Immigration and Nationality Act that repealed the severe immigration restrictions established by the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act (García 1997). The 1965 act led to an increase in the number of America Born Chinese (ABC) who, as a result of being immersed in the American educational system that “urges inevitable shift to English” (Wong 1988:109), have grown up speaking English natively. Tsang and Wing even assert that “the English verbal performance of native-born Chinese Americans is no different from that of whites” (1985:12, cited in Wong 1988:210), an assertion that requires closer examination. -

A Comparative Analysis of the Simplification of Chinese Characters in Japan and China

CONTRASTING APPROACHES TO CHINESE CHARACTER REFORM: A COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS OF THE SIMPLIFICATION OF CHINESE CHARACTERS IN JAPAN AND CHINA A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI‘I AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN ASIAN STUDIES AUGUST 2012 By Kei Imafuku Thesis Committee: Alexander Vovin, Chairperson Robert Huey Dina Rudolph Yoshimi ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express deep gratitude to Alexander Vovin, Robert Huey, and Dina R. Yoshimi for their Japanese and Chinese expertise and kind encouragement throughout the writing of this thesis. Their guidance, as well as the support of the Center for Japanese Studies, School of Pacific and Asian Studies, and the East-West Center, has been invaluable. i ABSTRACT Due to the complexity and number of Chinese characters used in Chinese and Japanese, some characters were the target of simplification reforms. However, Japanese and Chinese simplifications frequently differed, resulting in the existence of multiple forms of the same character being used in different places. This study investigates the differences between the Japanese and Chinese simplifications and the effects of the simplification techniques implemented by each side. The more conservative Japanese simplifications were achieved by instating simpler historical character variants while the more radical Chinese simplifications were achieved primarily through the use of whole cursive script forms and phonetic simplification techniques. These techniques, however, have been criticized for their detrimental effects on character recognition, semantic and phonetic clarity, and consistency – issues less present with the Japanese approach. By comparing the Japanese and Chinese simplification techniques, this study seeks to determine the characteristics of more effective, less controversial Chinese character simplifications. -

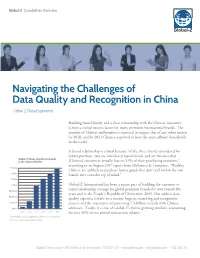

Navigating the Challenges of Data Quality and Recognition in China Global-Z China Experience

Global-Z Capabilities Overview Navigating the Challenges of Data Quality and Recognition in China Global-Z China Experience Building brand loyalty and a close relationship with the Chinese consumer is now a critical success factor for many premium international brands. The number of Chinese millionaires is expected to surpass that of any other nation by 2018, and by 2021 China is expected to have the most affluent households in the world. A brand relationship is critical because “of the three brands considered for luxury purchase, two are considered top-of-mind, and are the ones that Global-Z Shows Significant Growth in the Chinese Market (Chinese) consumers actually buy on 93% of their purchasing occasions,” according to an August 2017 report from McKinsey & Company. “Wealthy 7.5 Billion Chinese are unlikely to purchase luxury goods that don’t fall within the two 5 Billion brands they consider top of mind.” 2.5 Billion 1 Billion Global-Z International has been a major part of building the customer to 750 Million brand relationship strategy for global premium brands for over twenty-five years and in the People’s Republic of China since 2003. Our address data 500 Million quality expertise is built on a mature hygiene, matching and recognition 50 Million process and the experience of processing 7.5-billion records with Chinese 5 Million addresses. Today, it is one of Global-Z’s fastest growing markets, accounting 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 for over 50% of our annual transaction volume. Cumulative cleansing transactions processed on Chinese name and address data. -

The Effect of Pinyin in Chinese Vocabulary Acquisition with English-Chinese Bilingual Learners

St. Cloud State University theRepository at St. Cloud State Culminating Projects in TESL Department of English 12-2019 The Effect of Pinyin in Chinese Vocabulary Acquisition with English-Chinese Bilingual Learners Yahui Shi Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.stcloudstate.edu/tesl_etds Recommended Citation Shi, Yahui, "The Effect of Pinyin in Chinese Vocabulary Acquisition with English-Chinese Bilingual Learners" (2019). Culminating Projects in TESL. 17. https://repository.stcloudstate.edu/tesl_etds/17 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of English at theRepository at St. Cloud State. It has been accepted for inclusion in Culminating Projects in TESL by an authorized administrator of theRepository at St. Cloud State. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Effect of Pinyin in Chinese Vocabulary Acquisition with English-Chinese Bilingual learners by Yahui Shi A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of St. Cloud State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in English: Teaching English as a Second Language December, 2019 Thesis Committee: Choonkyong Kim, Chairperson John Madden Zengjun Peng 2 Abstract This study investigates Chinese vocabulary acquisition of Chinese language learners in English-Chinese bilingual contexts; the 20 participants in this study were English native speakers, who were enrolled in a Chinese immersion program in central Minnesota. The study used a matching test, and the test contains seven sets of test items. In each set, there were six Chinese vocabulary words and the English translations of three of them. The six words are listed in one column on the left, and the three translations were in another column on the right. -

Transfer of Perceptual Expertise: the Case of Simplified and Traditional Chinese Character Recognition

Cognitive Science (2016) 1–28 Copyright © 2016 Cognitive Science Society, Inc. All rights reserved. ISSN: 0364-0213 print / 1551-6709 online DOI: 10.1111/cogs.12307 Transfer of Perceptual Expertise: The Case of Simplified and Traditional Chinese Character Recognition Tianyin Liu,a Tin Yim Chuk,a Su-Ling Yeh,b Janet H. Hsiaoa aDepartment of Psychology, University of Hong Kong bDepartment of Psychology, National Taiwan University Received 10 June 2014; received in revised form 23 July 2015; accepted 3 August 2015 Abstract Expertise in Chinese character recognition is marked by reduced holistic processing (HP), which depends mainly on writing rather than reading experience. Here we show that, while simpli- fied and traditional Chinese readers demonstrated a similar level of HP when processing characters shared between the simplified and traditional scripts, simplified Chinese readers were less holistic than traditional Chinese readers in perceiving simplified characters; this effect depended mainly on their writing rather than reading performance. However, the two groups did not differ in HP of traditional characters, regardless of their difference in reading and writing performances. Our image analysis showed high visual similarity between the two character types, with a larger vari- ance among simplified characters; this may allow simplified Chinese readers to interpolate and generalize their skills to traditional characters. Thus, transfer of perceptual expertise may be con- strained by both the similarity in feature and the difference in exemplar variance between the cate- gories. Keywords: Holistic processing; Chinese character recognition; Reading; Writing 1. Introduction Holistic processing (i.e., gluing features together into a Gestalt) has been found to be a behavioral visual expertise marker for the recognition of faces (Tanaka & Farah, 1993) and many other nonface objects, such as cars (Gauthier, Curran, Curby, & Collins, 2003), fingerprints (Busey & Vanderkolk, 2005), and greebles (a kind of artificial stimuli; Gau- thier & Tarr, 1997). -

MATTER of WONG in Visa Petition Proceedings

Interim Decision #2165 MATTER OF WONG In Visa Petition Proceedings A-19168778 Decided by Board September 18, 1972. Since a visa petition involving a claimed adoptive relationship must be consid- ered from a factual point of view to determine if the claimed familial relationship is established, the instant visa petition to accord beneficiary fourth preference classification on the basis of her claimed adoption in Hong Kong in 1951 by the U.S. citizen petitioner's wife (allegedly unmarried at the time) is remanded to the District Director to make appropriate findings as to the factual validity of the adoption, with particular attention to the exploration of ques- tions raised by certain factual discrepancies relating to identity of the parties and the existence of the adoptive relationship, and to require the submission of supporting secondary evidence in the form of affidavits executed by petitioner and his wife, by witnesses to the adoption, and by relatives and neighbors. ON BEHALF OF PETITIONER: ON BEHALF OF SERVICE: Z. B. Jackson, Esquire R. A. Vielhaber 580 Washington Street Appellate Trial Attorney San Francisco, California 94111 (Brief filed) (Brief filed) The United States citizen petitioner applied for preference status for the beneficiary as his married adopted stepdaughter under section 203(a)(4) of the Immigration and Nationality Act. The District Director, in an order dated April 16, 1969, denied the application. From that order the petitioner appeals. The case will be remanded. The beneficiary is a female of Chinese ancestry who was born in Canton, China in 1948. She was purportedly adopted in Hong Kong in 1951 by Leung Wai Jun, at a time when Leung Wai Jun was not married. -

VI. Developments in Hong Kong and Macau

1 VI. Developments in Hong Kong and Macau Hong Kong During the Commission’s 2015 reporting year, massive pro- democracy demonstrations (‘‘Occupy Central’’ or the ‘‘Umbrella Movement’’) took place from September through December 2014, drawing attention to ongoing tensions over Hong Kong’s debate on electoral reform and Hong Kong’s autonomy from the Chinese cen- tral government under the ‘‘one country, two systems’’ approach. The Commission observed developments raising concerns that the Chinese and Hong Kong governments may have infringed on the rights of the people of Hong Kong, including in the areas of polit- ical participation and democratic reform, press freedom, and free- dom of assembly. UNIVERSAL SUFFRAGE AND AUTONOMY Hong Kong’s Basic Law guarantees freedom of speech, religion, and assembly; promises Hong Kong a ‘‘high degree of autonomy’’; and affirms the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) applies to Hong Kong.1 The Basic Law also states that its ‘‘ultimate aim’’ is the election of Hong Kong’s Chief Execu- tive (CE) ‘‘by universal suffrage upon nomination by a broadly rep- resentative nominating committee in accordance with democratic procedures’’ and of the Legislative Council (LegCo) ‘‘by universal suffrage.’’ 2 The CE is currently chosen by a 1,200-member Election Committee,3 largely consisting of members elected in functional constituencies made up of professionals, corporations, religious and social organizations, and trade and business interest groups.4 Forty LegCo members are elected directly by voters and 30 by functional constituencies.5 The electors of many functional constituencies, however, reportedly have close ties to or are supportive of the Chi- nese government.6 Despite committing in principle to allow Hong Kong voters to elect the CE by universal suffrage in 2017, the Chinese govern- ment’s framework for electoral reform 7 restricts the ability of vot- ers to nominate CE candidates for election. -

Developing Computational Tools for Cantonese Linguistics Jackson L

PyCantonese: Developing computational tools for Cantonese linguistics Jackson L. Lee, Litong Chen, & Tsz-Him Tsui University of Chicago & The Ohio State University Introduction: In this talk, we introducce PyCantonese, an open-source Python library for computational research in Cantonese linguistics. There are two primary motivations for this project. First, while an increasing number of Cantonese corpora are available (e.g., the Hong Kong Cantonese Corpus (Luke & Wong 2015), HKCAC (Leung & Law 2001, Fung & Law 2013), the Cantonese Radio Corpus (Francis & Matthews 2005)), these resources are in incompatible formats and there are no general toolkits for handling Cantonese corpus data. Second, computational linguistics is a largely undeveloped sub-field for Cantonese. In response to these gaps, PyCantonese is designed to provide general tools for the manipulation, annotation, and analysis of Cantonese corpus data. We demonstrate the implemented tools including the handling of Jyutping romanization and corpus search functions, and show how PyCantonese can facilitate Cantonese linguistic research. Handling Jyutping: A common scenario in Cantonese corpus work is that a corpus is available and transcribed in Jyutping, but no tools are readily available to parse Jyutping in order to identify onsets, nuclei, codas, and tones. We demonstrate the relevant functionalities of PyCantonese, and how they facilitate research areas such as phonotactics and phonological development using child-directed speech data. Search functions: Another frequent task is to search for particular items in corpus data. Depending on the exact nature of the dataset being used, PyCantonese provides search functions for some given Jyutping elements, part-of-speech tags, and Chinese characters. We show how simple searches are performed using PyCantonese, and how to combine these functions and programming techniques to achieve what would be of great interest to linguists (e.g., find verbal and prepositional phrases). -

Names of Chinese People in Singapore

101 Lodz Papers in Pragmatics 7.1 (2011): 101-133 DOI: 10.2478/v10016-011-0005-6 Lee Cher Leng Department of Chinese Studies, National University of Singapore ETHNOGRAPHY OF SINGAPORE CHINESE NAMES: RACE, RELIGION, AND REPRESENTATION Abstract Singapore Chinese is part of the Chinese Diaspora.This research shows how Singapore Chinese names reflect the Chinese naming tradition of surnames and generation names, as well as Straits Chinese influence. The names also reflect the beliefs and religion of Singapore Chinese. More significantly, a change of identity and representation is reflected in the names of earlier settlers and Singapore Chinese today. This paper aims to show the general naming traditions of Chinese in Singapore as well as a change in ideology and trends due to globalization. Keywords Singapore, Chinese, names, identity, beliefs, globalization. 1. Introduction When parents choose a name for a child, the name necessarily reflects their thoughts and aspirations with regards to the child. These thoughts and aspirations are shaped by the historical, social, cultural or spiritual setting of the time and place they are living in whether or not they are aware of them. Thus, the study of names is an important window through which one could view how these parents prefer their children to be perceived by society at large, according to the identities, roles, values, hierarchies or expectations constructed within a social space. Goodenough explains this culturally driven context of names and naming practices: Department of Chinese Studies, National University of Singapore The Shaw Foundation Building, Block AS7, Level 5 5 Arts Link, Singapore 117570 e-mail: [email protected] 102 Lee Cher Leng Ethnography of Singapore Chinese Names: Race, Religion, and Representation Different naming and address customs necessarily select different things about the self for communication and consequent emphasis. -

Intro Cover Page

EXCERPTED FROM Understanding Contemporary China THIRD EDITION edited by Robert E. Gamer Copyright © 2008 ISBN: 978-1-58826-594-4 pb 1800 30th Street, Ste. 314 Boulder, CO 80301 USA telephone 303.444.6684 fax 303.444.0824 This excerpt was downloaded from the Lynne Rienner Publishers website www.rienner.com Contents List of Illustrations ix Preface xi Acknowledgments xv 1 Introduction Robert E. Gamer 1 Creative Tensions 4 New Challenges 8 2 China: A Geographic Preface Stanley W. Toops 11 Space 12 Regions 15 The Natural Landscape 19 3 The Historical Context Rhoads Murphey 29 The Peopling of China 30 Political Patterns of the Past 34 Chinese Attitudes and Ours About China 57 4 Chinese Politics Robert E. Gamer 67 A Legacy of Unity and Economic Achievement 67 A Century of Turmoil 71 Unity Nearly Restored 75 Two Decades of Turmoil 80 Into the World Economy 84 Maintaining Unity 88 What Will Endure and What Will Change? 99 5 China’s Economy Sarah Y. Tong and John Wong 117 China’s Dynamic Growth in Perspective 118 China’s Traditional Mixed Economy 127 From Revolution to Reform 130 The Successful Transition to a Market Economy 131 Is High Growth Sustainable? 136 Overcoming Challenges and Constraints 141 v vi Contents 6 China Beyond the Heartland Robert E. Gamer 163 Overseas Chinese 163 Hong Kong 166 Taiwan 177 Tibet 183 Conclusion 195 7 International Relations Robert E. Gamer 205 China’s Foreign Relations Before the Opium Wars 205 From the Opium Wars to the People’s Republic 208 Foreign Policy Under Mao 210 The Cultural Revolution 217 Joining the -

Jade Snow Wong Teacher Packet (PDF)

Jade Snow Wong Image Courtesy of the Jade Snow Wong Family Teacher Packet © 2020 1 Table of Contents Introduction 3 Lesson 1. Jade Snow Wong: Breaking the Mold 5 Lesson 2. Drawing Together Jade Snow Wong’s Many Influences 9 Lesson 3. The Art and Science of Jade Snow Wong’s Work 12 Lesson 4. Jade Snow Wong: Crafting a Chinese American Identity 15 Lesson 5. Jade Snow Wong’s Writing: Shaping Her Story 19 Special thanks to Mark Ong for sharing his memories and insights into his mother’s life and work. 2 Introduction: Jade Snow Wong (1922-2006) was significant not just as a celebrated ceramics and enamels th artist but also as one of the first writers on the 20 -century Chinese American experience. The theme of “working with your hands” resonated throughout her life: she saw her immigrant parents laboring with their hands in their garment factory; she cooked and cleaned as a maid to pay for her college education; she wrote her best-selling memoirs by hand and on the typewriter; she personally handled matters (objects and tours) in her import/export and travel businesses; and, of course, she worked with her hands as a ceramics and enamels artist. This “hands-on” approach in all of her endeavors enabled Wong to create a strong sense of identity that withstood the expectations and judgments she faced as an Asian woman. The acclaim she received for her art and writing led the U.S. State Department to ask her to serve as a cultural ambassador speaking to audiences throughout Asia. -

NAMES: Getting Them Right

NAMES: Getting them right Reprinted with permission from: Asian Pacific American Handbook, by The National Conference for Community and Justice (NCCJ), formerly the National Conference of Christians and Jews, 1989, by NCCJ’s LA Region. There is one simple, sure-fire way for you to ensure you get the names right, in all references, of Asian and Asian Pacific American subjects: Ask them their personal preferences. This point is especially important with new immigrants, because some may still list their names in the style of their homeland (often, family name listed first) while others may have already adopted Ameri- can usages (family name listed last). But it also is a worthwhile practice to inquire about name preferences of Asians still in Asia who have long-standing associations with this country. They-or the American media-may have adopted Anglicized usages. For example, former South Korean President Park Chung Hee (family name of Park listed first) was often named in the American press as Chung Hee Park. Most Asian Pacific Americans who have been in this country for awhile will list their names in the American style-but you should always ask the preference. Based on discussions with writers, editors and other experts, publications such as the Los Angeles Times have set their own style rules for Asian Pacific name usages. While it is important for you to know your own organization’s style, here are some general guidelines about traditional name usage in Asian Pacific cultures: Chinese - Most Chinese names consist of two parts, a family name followed by a personal name.